Three neighbors make common cause: Andrea Zietzschmann, Hannes Langbein and Hermann Parzinger discuss the past and future of a one-of-a-kind cultural venue.

Mr. Langbein, you’re the director of the Stiftung St. Matthäus (St. Matthew's Foundation), which is currently exhibiting modern art at the Kulturforum in the church of that name, designed by Friedrich August Stüler. Given that the area is saturated with art, so to say, isn't that a bit like carrying coals to Newcastle?

Hannes Langbein: The idea of opening a dialog here between art and religious topics was actually a very natural one in the context of the Kulturforum. In the mid-1990s, Germany’s main Protestant church, the Evangelische Kirche, was wondering how to respond to its shrinking congregation here in the former Tiergarten quarter. Apart from that, of course, there is a close relationship between art and religion. We're just making that connection a bit more visible.

Looking ahead: SPK President Hermann Parzinger (left), Philharmoniker General Manager Andrea Zietzschmann (middle) and Pastor Hannes Langbein in front of the Philharmonie

You currently have a number of works on permanent display here, but you also present temporary exhibitions several times a year.

Hannes Langbein: Our exhibitions are scheduled around the seasons of the liturgical year. On average, there are three to four per year. Beyond that, we also organize projects in cooperation with the other institutions at the Kulturforum. One example, right now, is the Utopian Kulturforum, a large project about the history of the Kulturforum that we’re organizing together with almost all of our neighbors. It starts at the end of August.

So one could say that you’re close, not just in terms of physical distance but also in the sense of a shared outlook?

Andrea Zietzschmann: I think we have good chemistry. Each of us has a receptive and open-minded attitude toward the others.

Yet each of you is operating under different conditions. With the Stiftung St. Matthäus, Mr. Langbein has something like a small speed boat moored at the Kulturforum, whereas comparatively speaking, Mr. Parzinger is steering a tanker, given the eight different institutions in his case.

Hermann Parzinger: No, for me it's more of a fleet than a tanker. The Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation) is a large organization made up of many separate institutions. They share a common bond, but each institution has its own responsibilities. The Foundation does not intervene in the business operations of its institutions.

What unites them all are the architectural jewels they have at the Kulturforum. Some time after Stüler's church came Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie, which was built in the 1960s. What is it like, Ms. Zietzschmann, to manage such a wonderful institution, and in such a wonderful building?

Andrea Zietzschmann: You really live with the architecture here. All of the musicians and visitors who come to this building feel the same way. Every touring orchestra probably has its favorites: high on the list for all of them are the Philharmonie in Berlin and the Musikverein in Vienna. You can see how unique our building is just by looking at how often people have tried to recreate this architecture in other places. With its Grand Hall laid out in the vineyard style, it is spacious and incredibly beautiful; there are endless ways to use it. It is focused on the idea of gathering the community around music. Scharoun, of course, wanted the Kulturforum to be a lively place.

But many of Scharoun's ideas were never realized. In addition to the Philharmonie, for example, he wanted to build a guest house for artists. Would the area be more lively today if the planners had gone "full Scharoun"?

Andrea Zietzschmann: As far as it not being lively, I think that’s improved quite a lot in recent years. But we still need to create a better connection to the Tiergarten some time. People like to go for walks and spend time there, but they seldom venture across Tiergartenstrasse to us. Maybe a footbridge is needed.

Hannes Langbein: A bridge like that was certainly planned at one time – like so much else that was ultimately never built.

In the 1960s, people entertained the idea of creating a Museumsinsel (Museum Island) of the West. Mr. Parzinger, you probably know the historic Museumsinsel in Mitte, the city’s central district, better than anyone. Did that vision ever become a reality here?

Hermann Parzinger: Something like a second museum island did emerge here back then, right near the Berlin Wall. The focus was different, though. In Mitte, it was mostly about archeology. Here at the Kulturforum, it was medieval, early modern and modern art in all its various forms. Here you find painting, graphic arts, decorative arts, and the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library). It's a magnificent ensemble, a wonderful complement to the Museumsinsel.

Many great architects have designed buildings here. But the most significant among them are still Scharoun and Mies van der Rohe. How important are their buildings today for the branding of your institutions?

Andrea Zietzschmann: Scharoun’s building is very important to us. Of course, the orchestra already had a really great reputation before that. But the building gave it another big boost. It helped define the era of Herbert von Karajan, who gave many of his greatest performances here. The building is – and always will be – an icon.

Hermann Parzinger: I see the Neue Nationalgalerie in a similar light. For me, it’s one of the greatest museum buildings anywhere. We are blessed by fortune at the Kulturforum. The architects who built here completely reimagined what a museum, concert hall, or library could be. They expressed visionary ideas in architecture. That's what continues to make these buildings so powerful and this location so special.

Doesn't its magnificence also lie in the contrasts – here, the austere architecture of Mies van der Rohe and there, the playful, almost suspended structures of Scharoun?

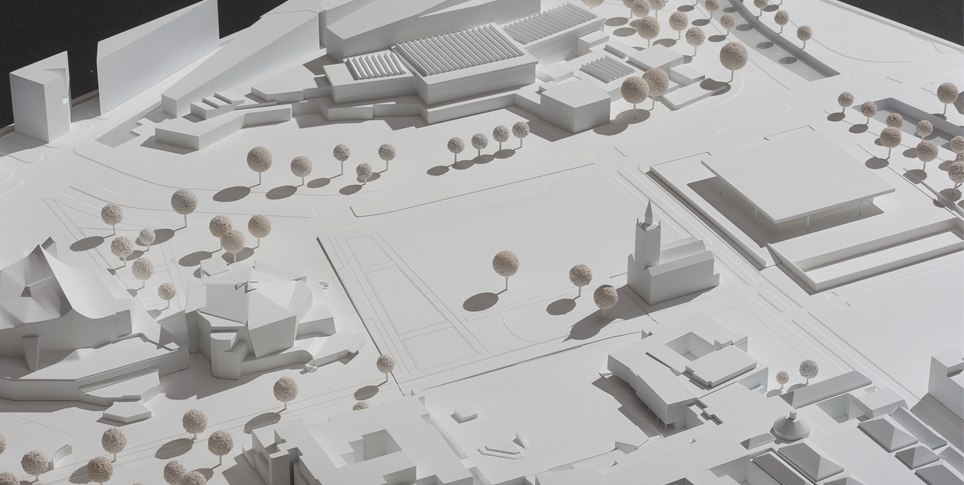

Hermann Parzinger: Definitely. The resulting tension was also a key aspect of the competition to design the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (Museum of the 20th Century). There were the two reference points of Mies and Scharoun. Icons of their time. You can hardly imagine a contrast more extreme. Putting something between these poles that would serve as a connecting element but still be an independent structure in its own right… that was the actual challenge of the competition.

Hannes Langbein: At the same time, with the choice of material and color in their design, Herzog & de Meuron are clearly referring to the architecture of the church. I think the productive tension of the Kulturforum also stems from the different strata of its history. It has become a collage of many different layers: the old Tiergarten district, the 1960s, the 1990s, and the present, including the history of demolition by the Nazis and destruction from the war. That is the actual richness of this area. Now the hope is that this will all fit together in the eyes of the general public, too.

As long as we're on the subject of the Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron: Ms. Zietzschmann, you experienced their skill at creating powerful forms during your time at the Elbphilharmonie (Elbe Philharmonic Hall). Does that make you all the more eager to welcome your new neighbor?

Andrea Zietzschmann: With the Elbphilharmonie, Herzog & de Meuron designed a fantastic building that repositioned Hamburg as a top destination for music. The Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts faces a completely different challenge. I am excited about the design. I'm sure it will be a major asset for the area.

Why did the Neue Nationalgalerie need a new building in the first place?

Hermann Parzinger: The collection of the Neue Nationalgalerie suffered immense wartime losses. The Nazis burned at least four hundred works of so-called degenerate art. After the Second World War, the Neue Nationalgalerie was rebuilt with great dedication and effort.

Today, it is again considered one of the largest and most important collections of the twentieth century. The only problem is that it doesn't have enough room. And in recent years, there have been some magnificent donations, like Ulla and Heiner Pietzsch’s collection, which highlights the intersections between early modernism and post-war modern art. We want to unite the art of the twentieth century at the Kulturforum, and that requires a new building. Mies and the new building – only the two of them together can convey the experience of the last century.

People will be able to experience something of this idea when the Neue Nationalgalerie reopens in August after five years of renovation.

Hannes Langbein: Yes, you can already sense that the Kulturforum is undergoing a change. The new Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts will open in 2026, at the earliest. But you’ll notice, the prospect alone is causing a stir – and that’s just as true for all of us here, too. It’s something to look forward to.

Hannes Langbein

The current director of Stiftung St. Matthäus (St. Matthew's Foundation) studied theology in Heidelberg, Zurich, Princeton and Berlin. He later worked as an aide in the cultural affairs office of the Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland (Evangelical Church in Germany). Langbein completed his training for the ministry in the parish of St. Nicholas in Spandau, Berlin, and then became a pastor in probationary service at the foundation. Langbein is also one of the editors of kunst und kirche, a magazine dedicated to contemporary art, architecture and religion.

Hermann Parzinger

The president of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz is a prehistorian. He still directs research projects and publishes regularly. Parzinger has received numerous awards, including the Leibniz Prize and the order of Pour le Mérite for the Sciences and Arts. He is a member of the British Academy, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences and Humanities, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society.

Andrea Zietzschmann

Andrea Zietzschmann has been the general manager of the Berliner Philharmoniker since 2017. She studied musicology, art history, and business administration in Freiburg, Vienna, and Hamburg. She was appointed manager of the orchestra at Hessischer Rundfunk in 2003 and became the head of music in 2008. In 2013, she moved to Hamburg, where she was manager of the ensembles of the broadcaster NDR.