A rediscovery for the music of everyday life: “The Jewish-German Song Book of 1912” is another credit to the great arts patron and Berliner James Simon.

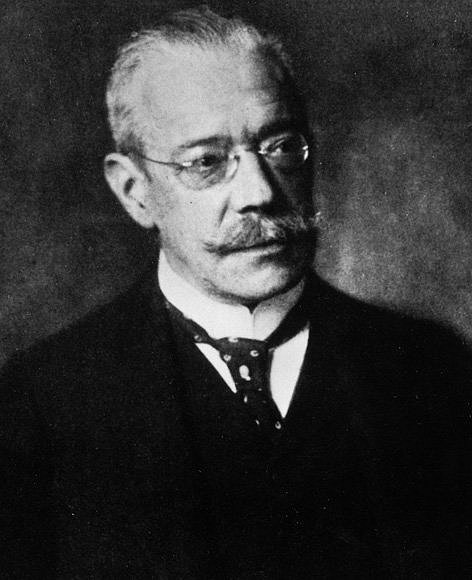

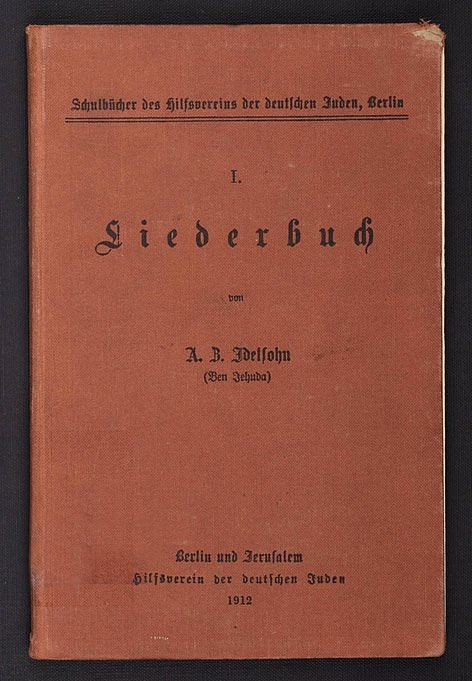

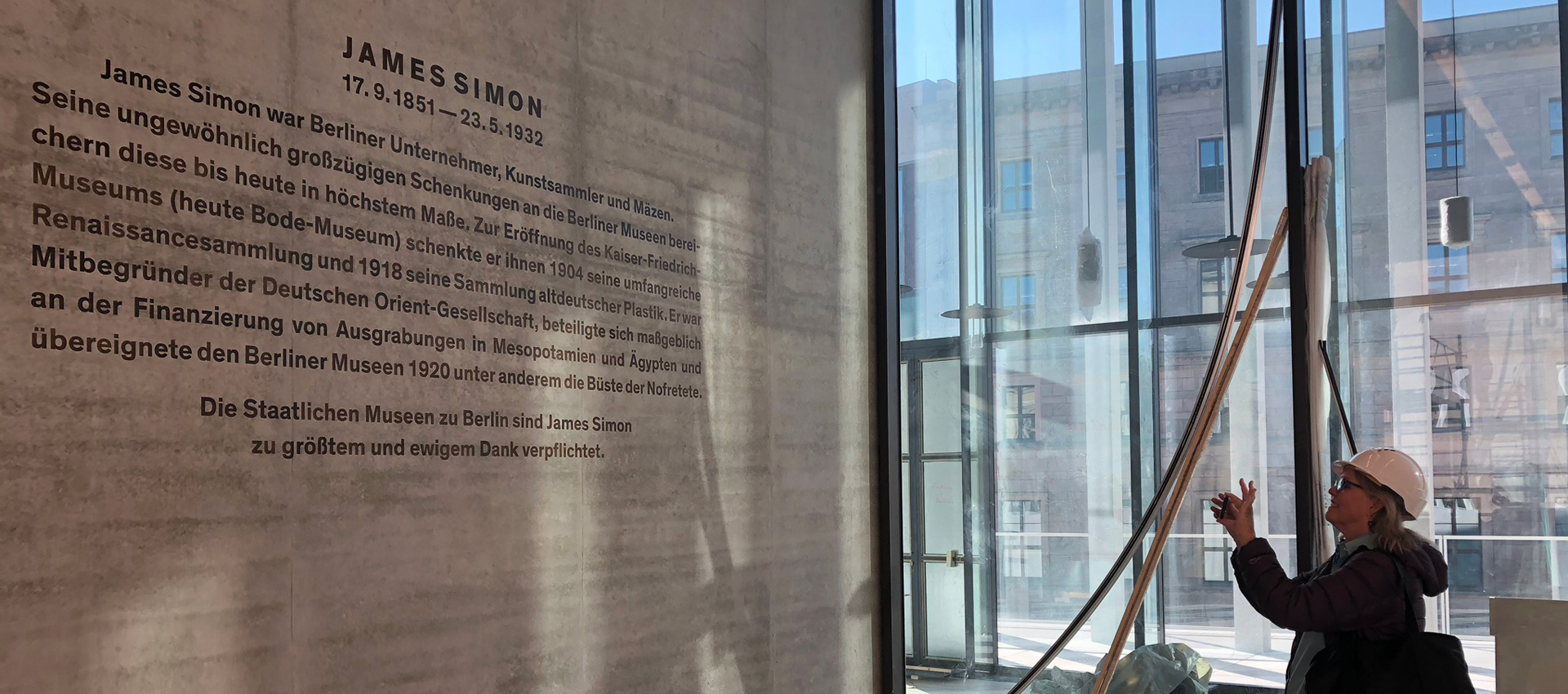

Businessman, patron, art lover, philanthropist, cosmopolitan: the many facets of James Simon, who donated more than 10,000 cultural works that are now spread among seven collections at the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin). What is less widely known, however, is that Berlin’s most important and most generous founder and sponsor of cultural initiatives also loved and supported music. One such example has recently come to light: “The Jewish-German Song Book of 1912,” published by the “Hilfsverein der deutschen Juden Berlin und Jerusalem” (Berlin and Jerusalem: Aid Association of German Jews), of which James Simon served as president until his death in 1932. In addition to countless other charitable activities, the association provided assistance to Jews who wanted to emigrate overseas, or to Palestine, but lacked the necessary financial resources.

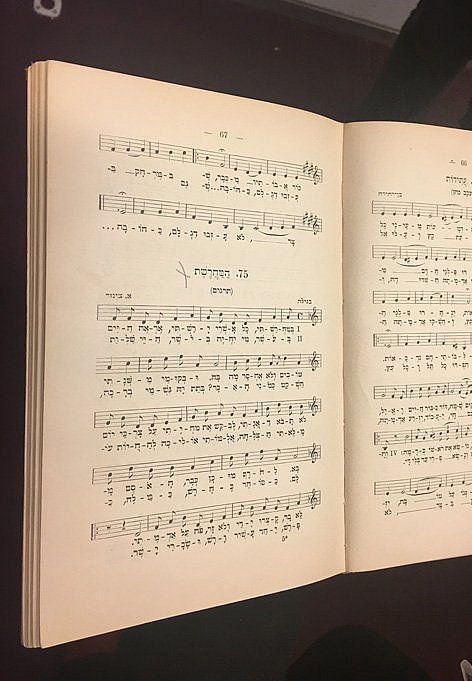

The song book of 1912 was an ideal travelling companion, and it helped potential emigrants prepare for their destination, too. It was printed in German and Hebrew and contained 49 German and 149 Jewish songs with easily followed melodies and singable texts – songs that were not difficult, but were yet substantial in the sense of having a rich tradition. This selection and the juxtaposition of German and Hebrew songs make it a fascinating and even unique document.

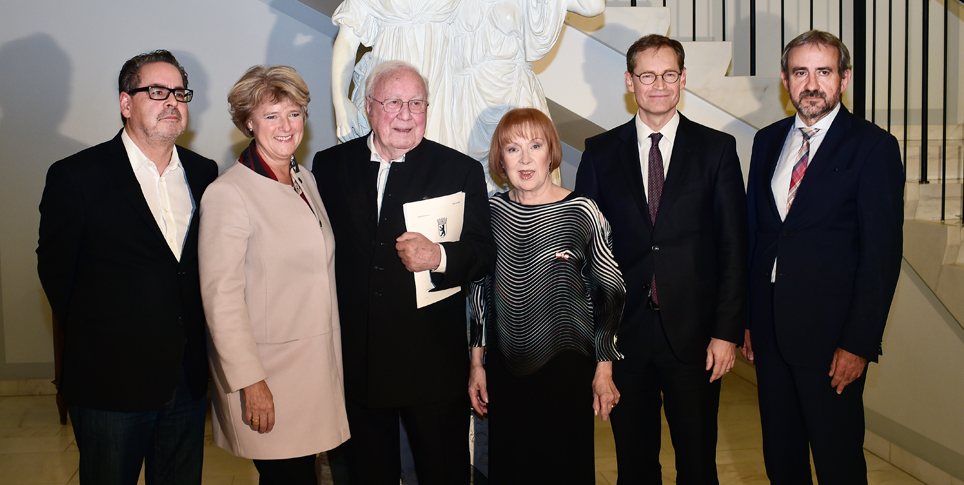

Unfortunately, only a few copies of the book remain – one of them is held by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library). Recently, a new edition of this 110-year-old testament to an era was presented in a ceremony at the basilica of the Bode-Museum. The event was attended by Professor Hermann Parzinger, President of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), and Dr. Felix Klein, Federal Government Commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight against Anti-Semitism, and the music performed there was quite a pleasure to hear.

The German folk songs sung by the girls’ choir of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin and the Jewish songs performed by Maria Doormann (vocals), Boyana Robillar (guitar) and Julia Katemann (violin) left the audience eager for more.

Typically German tunes and Jewish songs from throughout Europe

Singing, wrote James Simon in his preface, is important not just “for the entire emotional life of a child, the development of its appreciation of nature and art,” but is also “a first-rate aid for language instruction.” In that respect, it served as a marvelous tool of communication for prospective emigrants and for music lessons in kindergartens, primary schools and secondary schools in Palestine and the diaspora. It preserved the connection to the original homelands and at the same time laid the basis for emigrants to put down roots in their new countries. The original Jewish-German song book was a simple, brown, cloth-bound book made for everyday use. It was conceived by the cantor, composer, conductor, and musicologist Abraham Zvi Idelsohn (1882–1938). His “Sefer Ha-Shirim: Jewish-German Song Book of 1912” was designed as a basic text for music instruction.

Its German songs were classics ranging from “Lorelei” to “Lindenbaum” and were considered “typically German.” They included folk songs and art songs from the likes of Franz Schubert, Louis Lewandowski and Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy.

Idelsohn selected the Jewish songs in the hope that they “corresponded, on the one hand, to the world of children and, on the other hand, to Zionist ideology.” He composed several of the vocal pieces himself, and he took others from the vocal reservoir of Jewish communities throughout Europe, according to Gila Flam of the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. In 2019, she rediscovered the book in the music archive there and oversaw the new edition. The “Projekt 2025 – Arche Musica” arranged for the publication of the new work, which was produced in cooperation with the publishing house of Schott Verlag in Mainz.

Jüdisch-deutsches Liederbuch (1912)

Deutsch-Jüdisches Liederbuch „Sefer Ha-Shirim“ (1912) – bearbeitet von A. Z. Idelsohn

New edition edited by Gila Flam, 244 pages, 24.50 euros, published by Schott Music Mainz

Expanding our musical canon with Jewish songs

The publisher Schott faced a very complicated task, considering that the Hebrew section in the first edition is not typeset from left to right, as in the German version, but rather from right to left. That part of the historic original therefore had to be reversed in the new edition, and of course the stems of the musical notes had to be mirror-inverted as well.

The lyrics were translated from Hebrew (the originals are also included), transcribed into Roman script and inserted to match the vocal lines. This newly recovered treasure trove of songs has thus been saved from oblivion and presented in a very accessible work that puts the material in a usable form for modern audiences with the aim of bringing it to practicing German musicians and vocalists, and ideally to music courses in schools.

With this new edition, the German-Jewish culture of remembrance gains an additional musical element and a new tool for the active prevention of antisemitism. As Gila Flam has put it, the song book builds “a symbolic bridge between Western music history and Jewish national culture, between German music and Hebrew music. Although only a few of Idelsohn’s melodies are in circulation, his Hebrew language strategy of integrating foreign songs into the national musical canon has become a fundamental, established approach for later Hebrew song.”

Productive contacts have now been established with the Deutscher Chorverband (German Choral Association, or DCV), which has almost a million members who routinely sing at association events – a pleasure appreciated all the more following the social distancing of the COVID-19 pandemic. If all goes according to plan, songs from Idelsohn’s book will have been rehearsed in time for performance at the DCV-organized Chorfest 2025 (Choir Festival) in Nuremberg. A promising start has been made in any event with this magnificent and commendable publication!