In its centenary year, the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung is paying tribute to an important pioneer with a commemorative plaque and two publications: Curt Sachs, the father of the scientific study of instruments, was the head of the collection of old musical instruments from 1919 until 1933, when he was dismissed from his position because of his Jewish origins and was expelled from Germany.

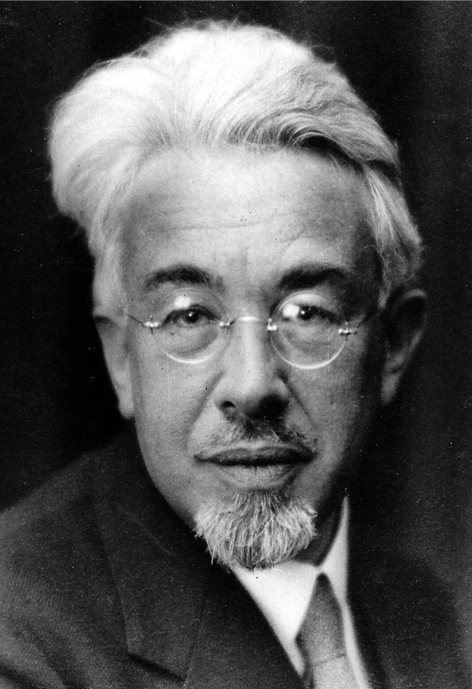

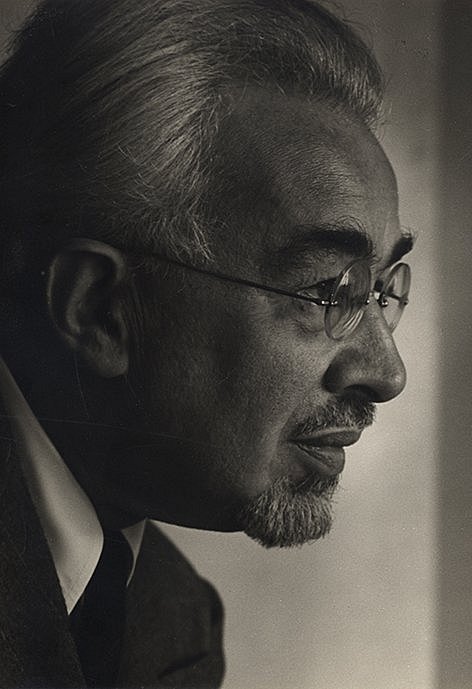

The large concert hall of the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung (State Institute for Music Research), characterized by pale wooden paneling and organic forms designed by architect Edgar Wisniewski, is named after Curt Sachs. Now, on the occasion of the Institute's centenary, a memorial plaque to him has been put up in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum (Museum of Musical Instruments). Born in 1881, he was a cultural scientist, instrument expert, and music historian. But who was Curt Sachs really and why should he be remembered with deeply felt respect, as the plaque – hopefully for always – states?

In 1917, when the Fürstliche Institut für Musikwissenschaftliche Forschung (Prince’s Institute of Musicology Research) was established in Bückeburg, Curt Sachs worked there as a private tutor without a permanent position; later, he would chair the Bückeburg Institute’s expert committee on the study of instruments. By this time, he had earned his doctorate in art history and, showing a strong affinity for musical studies, had already written some of his most important works, notably the “Musikgeschichte der Stadt Berlin bis zum Jahre 1800“ (Music history of the city of Berlin up to 1800), the “Real-Lexikon der Musikinstrumente“ (Practical lexicon of musical instruments), and “Die Musikinstrumente Indiens und Indonesiens““ (The musical instruments of India and Indonesia).

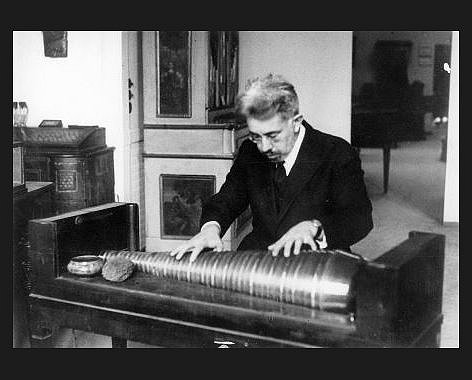

In 1919, Sachs qualified as a lecturer at the University of Berlin with the publication of his work “Handbuch der Musikinstrumentenkunde“ (Handbook of Musical Instrument Studies); in the following year, he was appointed director of the collection of old musical instruments at the State College of Music in Berlin's Charlottenburg district, which has since become the Musikinstrumenten-Museum. Beside fulfilling his responsibility to preserve and present the wide-ranging and precious collection of more than three thousand objects, Sachs successfully worked to acquire additional rarities. His main aim, however, was to make the instruments accessible and usable for scholarly purposes. He took a comprehensive and innovative approach to doing so, as Martin Elste, who compiled the anthology “Of Collecting, Classifying and Interpreting“, describes:

“In contrast to many of his colleagues, Curt Sachs trod new ground in many fields: musical ethnology, the study of musical instruments, aspects of classification and, last but not least, the presentation of research findings in non-print media. He was the driving force behind the production of records of early music at a time when it was only a minority interest.

Some of his writings have a lexicographical character, while others are superficial but pithy, introductory essays. What they all have in common is that Sachs does not analyze compositions, but explores the characteristics that various musical phenomena have in common and classifies them systematically in the manner of a phenomenological survey.”

Sachs took a broad view and an integrative approach, both chronologically (going back two thousand years, as his record series shows) and universally, putting the whole world of musical instruments into perspective and, later, that of dance (“A World History of Dance“). So if you were looking for the Alexander von Humboldt of musicology, you would find him in the person of Curt Sachs.

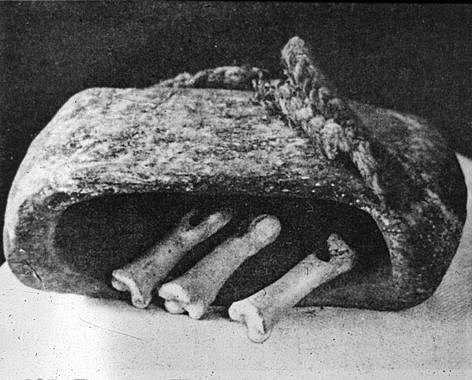

“Sachs,” writes Martin Elste in the New German Biography“was one of the most versatile and prolific musicologists, an analytically minded scientist and one who sought intellectual synthesis. Taking a hermeneutic historical approach, his essay Geist und Werden der Musikinstrumente (Spirit and genesis of musical instruments) of 1929 – one of the most important examples of the so-called cultural sphere discourse – offers a chronological analysis of musical instruments from the Stone Age to the Middle Ages that is based on the premises of cultural geography and emphasizes universal historical connections.”

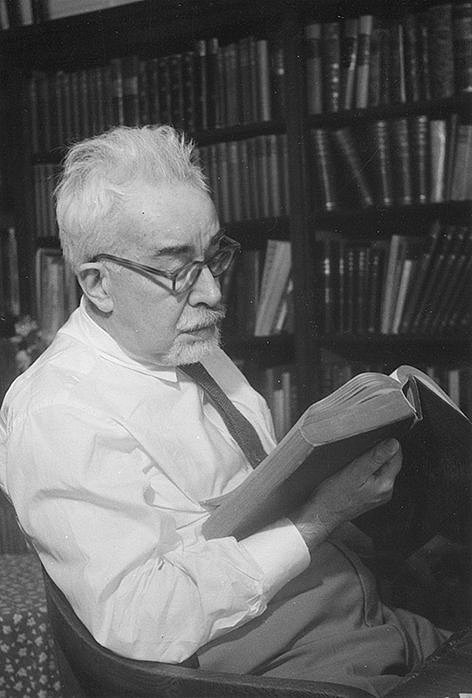

Then came 1933 and the events that ultimately forced Curt Sachs to emigrate. Alfred Berner, a pupil of Sachs's who became the director of the Musikinstrumenten-Museum after the Second World War, met him during his last months in office:

“Sachs was still active in the collection when I returned to Berlin in July 1933, and I immediately went to find him there. But he knew, of course, that he would not be staying for much longer, and I felt his pain and embitterment. He had always thought of himself as a German, and German was his mother tongue from birth. And then he told me, with an inner agitation that I will never forget, that there was a notice downstairs in the lobby of the university that stated, ‘when the Jew speaks German, then he is lying.’ […] A man who had given us so much linguistically, whose stimulating, vivid, and always brilliantly formulated lectures were very popular, now had to put up with a sentence like that without being allowed to refute it openly.”

Sachs went to Paris, where he worked as a research associate at the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro with the help of a Rockefeller scholarship and assistance from the Alliance Israélite Universelle. To begin with, his family remained in Berlin, and in 1935 he returned there for a short time. In 1937, the entire family moved to New York, where Curt Sachs became a lecturer at New York University. He died in that city at the age of 78 in 1959.

In the publication issued by the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung in commemoration of Curt Sachs, Annette Otterstedt assesses the effects of the anti-Semitism he experienced:

“Numerous seminal works testify to his tremendous productivity, the like of which hardly any other musicologist can demonstrate. Nevertheless, in the context of his times, he appears as an outsider, hardly ‘toeing the line’ in the ranks of his colleagues. So it is not surprising that he did not return to Germany after the war. His kind of science did not fit with the way in which science was then being practiced in Germany.

The case of Curt Sachs also shows that Jews, even if they were outstanding scholars, had few opportunities even before the Nazi era, and even if he had not needed to emigrate, he would hardly have been able to take a pioneering role given the anti-Semitic climate of the times.”

His emigration allowed his ideas and his work to spread elsewhere in the world, but as far as Germany is concerned, Otterstedt says “we squandered the huge opportunity that Curt Sachs represented.” It is precisely this “squandered opportunity” that makes his commemoration this year all the more important.