The buildings of the Kulturforum have their praises sung to the architectural heavens and their names cursed to the depths as a city planning nightmare. What is the balance of opinion on the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung?

When Hans Scharoun created his design for the Kulturforum in the 1960s, city street plans of the time called for a multi-lane urban freeway to be built with long entrance and exit ramps where the entrance to the Musikinstrumenten-Museum (Museum of Musical Instruments) is located. From here, you could gaze over the Hermann Mattern Garden to the Philharmonie concert hall, standing in splendid isolation. But, just as new districts grow up around old town centers, Edgar Wisniewski erected several buildings around the Philharmonie after the death of Scharoun, who had been his teacher and later architectural partner.

In the meantime, the Tiergarten tunnel had been built instead of the city freeway, mercifully taking part of the road traffic underground. So today the Musikinstrumenten-Museum stands on the side of Ben-Gurion-Strasse (with five lanes nonetheless) as a slim counterpart to the glass expanse of the Sony Center.

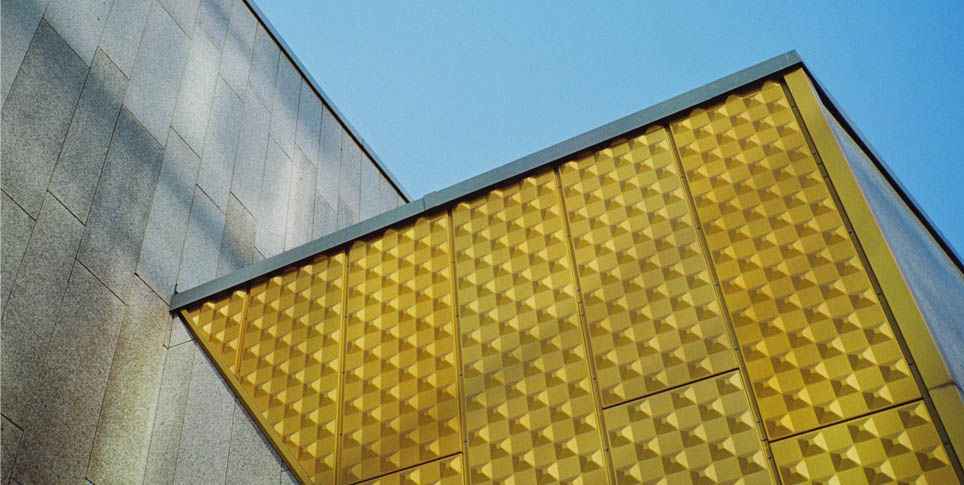

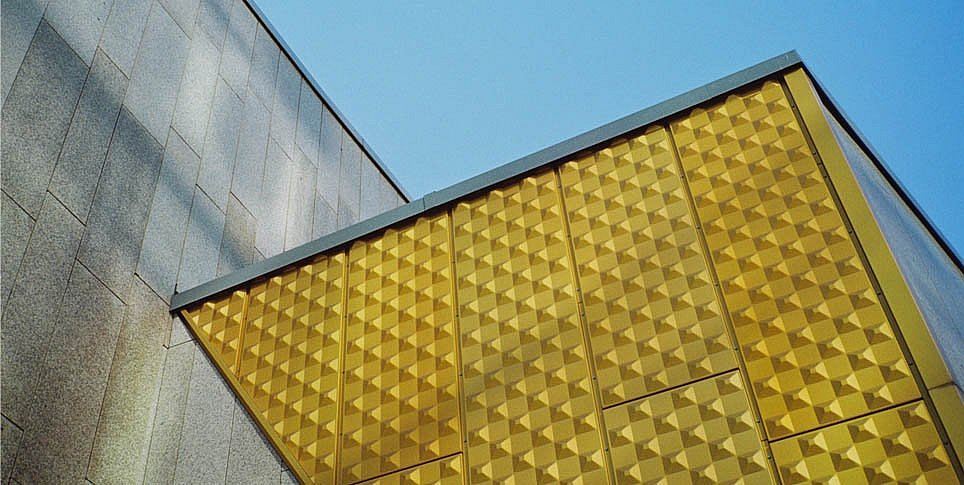

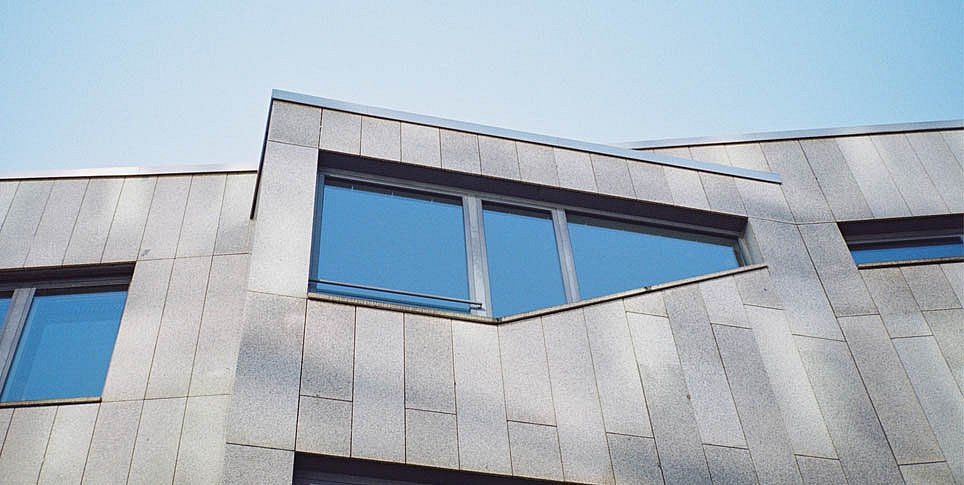

From the outside, the building makes a rather undecided impression. References to the Philharmonie, with which it is directly connected, are clearly recognizable, but the organic elegance of Scharoun's architecture has not been well served by this posthumous “update” from the 1980s. If you are looking for a monumental statement dressed up in a strikingly developed external form, like the Staatsbibliothek and the Philharmonie, you won't find it in this building, with its cladding of gray stone panels. Admittedly, the composition of the structures at the front of the Staatsbibliothek is also difficult to decipher, but the golden bulk of the main building does give the visitor an inkling of the volumes interwoven in its impressive interior. That is not the case with the Musikinstrumenten-Museum, where the eye is caught more by fire hydrants, parking barriers, bicycle stands, and other paraphernalia of everyday city life, since its almost modular composition deliberately avoids striking a pose outwardly.

Once you have passed through the slightly awkward entrance area, however, you find yourself in an unexpectedly large and well-lit space that demonstrates all of the virtues of organic architecture afresh. In a pleasant atmosphere of natural light, wood, carpeting, and stone in warm colors, the interior unfolds continuously as a series of slightly offset platforms, like terraces.

With astonishing suppleness, the space flows through the lower floor with the museum café and opens out to create a performance area on the upper floor.

Occupying a fairly central position is the Mighty Wurlitzer cinema organ: an instrument that has come to be part of the space itself. At the periphery, on the other hand, you are repeatedly stumbling over unloved spatial left-overs, an unintentional manifestation in built form of the conflict that arises when the architect's exuberant urge to create fluidity and an interplay of forms and spaces comes up against the hard facts of the museum's daily operation and is found wanting. If any further proof were needed, the clumsy design of some of the railings, room dividers, and staircases confirms that a Wisniewski is simply not a Scharoun.

Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung

Das Staatliche Institut für Musikforschung ist das größte außeruniversitäre Forschungszentrum für Musikwissenschaft in Deutschland. Es widmet sich der historisch-theoretischen Reflexion über Musik und deren lebendiger Vermittlung. Hierfür präsentiert es in seinem Musikinstrumenten-Museum die Entwicklung der europäischen Kunstmusik vom 16. bis zum 21. Jahrhundert für ein breites Publikum. Bereits 1888 gegründet, besitzt das Museum über 3.000 historische Musikinstrumente und bietet vielfältige Veranstaltungen – vom wissenschaftlichen Symposion über Gesprächs-Konzerte auf historischen Instrumenten bis hin zu interaktiven Klanginstallationen.