The Staatliche Institut für Musikforschung and the Musikinstrumenten-Museum are breaking new ground in outreach – Conny Restle and Thomas Ertelt talk to us about sonorous objects, Beethoven the freelancer, and the parking lot.

The digital museum guide at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum (Museum of Musical Instruments) of the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung (State Institute for Music Research) is a runaway success. It offers visitors a completely new experience of the museum next to the Berlin Philharmonie, transforming it into a sonorous structure in its own right, besides the many concerts that are held inside it. May 5, 2019 marks the start of a multimedia project titled “Magical Musical Instruments (and where to find them)”, which is funded by Berlin’s department of culture. It centers on a tour for children and adults in five languages, which seeks to convey the magic of historical instruments. That’s a good reason for talking to Conny Restle, Director of the Musikinstrumenten-Museum, and Thomas Ertelt, Director of the Staatliche Institut für Musikforschung, about new ways of opening up to the public.

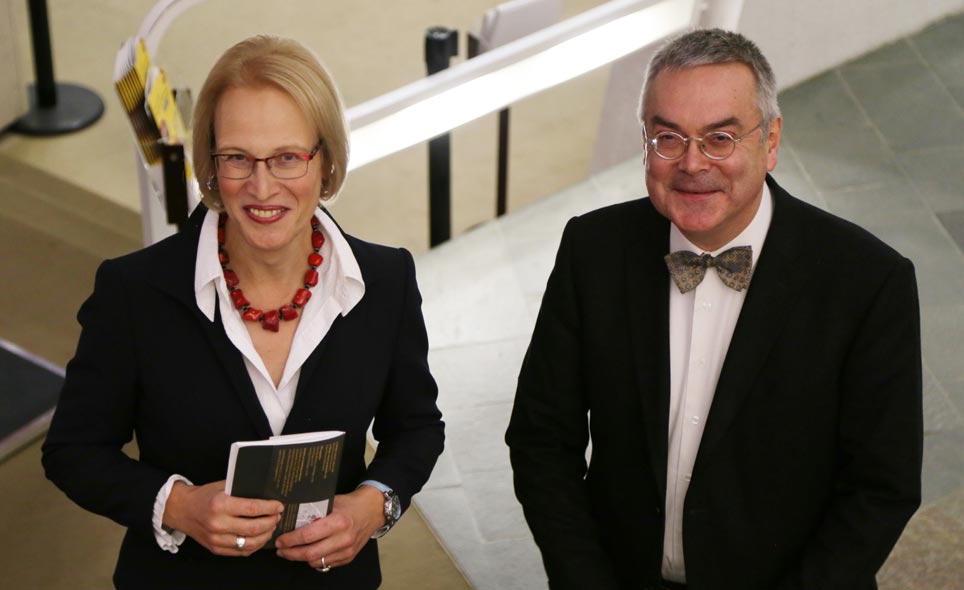

Conny Restle and Thomas Ertelt © SIMPK / Jörg Joachim Riehle

The Musikinstrumenten-Museum is undergoing a re-think. New means of outreach, different approaches, a more modern way of connecting with visitors. What does the way ahead look like?

Conny Restle: The permanent exhibition dates from 1984, when the museum first opened. We now have three times as many objects in the display collection as we did then. And we have gained new insights and experience in outreach work and museum education. For a year now, we have been working on a new concept, with which we certainly aim to keep the positive aspects of the current exhibition, but instead of offering a chronological presentation for looking at, we will go much more into contextual topics. For example, how did court music develop, or the bourgeois music culture of the nineteenth century, and what paths did film music evolve along? These are the kinds of topic that we would like to address. I think we will have a combination of chronological and interpretive presentations. Nothing like it has yet been done in comparable museums.

You mentioned new insights in outreach work. What exactly were you referring to?

Restle: If we want to attract younger visitors, we have to realize that they use tablets and smartphones as a matter of course. That’s the starting point for our digital museum guide, developed by a new Berlin start-up, shoutr labs. Much of the information that we can give people about our collection – audio samples, patents, documents, glimpses into instrument makers’ workshops – can be accessed with this web-based guide. Every visitor can share his or her ideas, impressions, and questions about objects, which our experts will respond to directly, as quickly as possible.

Is such a guide all that is needed as a means of outreach?

Restle: Of course not. Our educational program is very broadly based. We have to convey the fascination, the joy of the objects. We have been doing that successfully for a long time with concerts and workshops. I think that the museum is one of the few places where we can experience what it means to be human. And here, that doesn’t mean just working, eating, and getting through the day, but the significance of using an instrument: making music, being creative. As for the instrument itself, for one thing there is the matter of the material. Where do you still come into physical contact with so many different organic materials these days? There are rare kinds of wood, and ivory. For another thing, the instruments were built to be played, which opens up all kinds of emotion. The Musikinstrumenten-Museum will remain attractive if we don’t just look back, but also ask how instrumental music is created. How did it come into being in the past and how does it come into being today? And we shouldn’t forget that we have to keep up with the Kulturforum. In a few years time, the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (Museum of the 20th Century) of the Nationalgalerie will open; changes are being made at the Philharmonie, and the Staatsbibliothek (Berlin State Library) is due for restructuring over the next five to ten years.

Thomas Ertelt: We are a research institute for music, and musicology is traditionally considered an esoteric subject. Nevertheless, we are in a location with a vibrant musical life into which a lot of money goes. I think that musicology and concerts complement each other well – and with our museum, we have the ideal forum for demonstrating that. Lectures alone aren’t enough to satisfy anybody nowadays; but people are interested in experiments and they like having a chance to try them out.

Does this mean that research work will feature even more prominently in the museum, with the museum becoming an even larger showcase for the institute?

Ertelt: That’s right. We want to be known for more than our very successful publications in the ongoing “History of Music Theory” series, which experts regard highly and which we do not have to publicize. We also want to connect with broader circles of people interested in music. We won’t reach such target groups with a nice treatise by Guido von Arezzo, but with events about performance practice, the interpretation of music, or aspects of transparency and tempo – not to mention the experiments on perception in our virtual concert hall. Our idea is to set up a listening room or audio lab in the Musikinstrumenten-Museum, where we can present the results of such research on a permanent basis.

You publish a lot, things like the correspondence between figures of the Vienna School, and the Bibliography of Music Literature.

Ertelt: Yes, we continue to do that and it is going well. Regarding the Bibliography of Music Literature (BMS online), I ought to mention that for some years we have also been the main supplier of information for our competitor and partner, RILM (Répertoire International de Littérature Musicale). We have provided the most input to the RILM, ahead of China and well ahead of the United States. That is anything but a matter of course.

Let’s talk about two anniversaries that your institutions are awaiting with bated breath: the Bauhaus in 2019 and Beethoven in 2020. What is planned for those?

Ertelt: On September 5, 2019, members of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester (German Symphony Orchestra) will perform Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire and Stravinsky’s L'Histoire du soldat (“The Soldier’s Tale”) in the Curt Sachs Hall. Schönberg was associated with an active focus on contemporary music at the Bauhaus; Stravinsky’s work was performed during the Bauhaus Week in 1923, which also featured compositions by other greats of modernism such as Ferruccio Busoni and Paul Hindemith. We are also in consultation with the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library), which is preparing an exhibition with the title Moholy-Nagy and New Typography. Moholy developed a variety of ideas that relate to underlying trends in the mechanization of the arts. For example, there were experiments with phonograph records, which were scratched and played at the same time, live – just like DJs do today. This is where we come in, because drawing on the partial bequest of the estate of Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt, a music critic who knew Moholy well, we can contribute to the topic of music’s interaction with the other arts.

And what about Beethoven?

Restle: Beethoven studied instruments intensively. He was brought up to play the violin, piano, and organ in Bonn. We are lucky to have three playable fortepianos in the collection that coincide with this period nicely. And then there is brass music. As a young man in Vienna, Beethoven wrote marvelous brass music for court ensembles. He also wrote compositions for a number of friends and acquaintances, including a mandolin player from Bohemia. This will all be reflected in our program. And then there is the so-called Beethoven string quartet: Beethoven was given four string quartet instruments by Prince Lichnowsky. These instruments have been on permanent loan to the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn since it was established as a museum. We will display these instruments, which come from our inventory, in Berlin for around six weeks and they will also be played in a concert.

I have also heard something about a Beethoven lounge.

Restle: That is our outreach program, “B and me”. This lounge offers many ways of getting to know Beethoven. There will be a composer’s desk as a selfie motif, a blackboard on which to write the reasons why you love or hate Beethoven, a multimedia kiosk, composition workshops, and so on. We want to lower people’s inhibitions about music and show them that it is fun – and that you don’t need to be a genius for it. In addition, Beethoven was – in today’s terms – a freelancer. We want to convey what that meant in his day.

Have most of the children and young people who visit you already had some musical training?

Restle: It varies greatly. Nowadays, music lessons are hardly given any more in many secondary schools. That means we have to make up for an awful lot. I always notice how the eyes of children and young people light up with enthusiasm when we explain to them how music is created and how the various instruments work. And when they feel what it’s like to hold a violin in your hands.

A question about the Kulturforum: how do you network – for example with your colleagues at the Berlin Philharmonie?

Ertelt: We not only have an intellectual link to the Philharmonie, but a real connecting door. We actually want to open up a lot more in that direction, especially in order to achieve more together in the areas of education and outreach. There is also a lot of potential within the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation). For example, this year we have an exhibition on the history of the bandoneon, with the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut (Ibero-American Institute). Another project under consideration with the IAI is on the spread of the barrel organ. It was exported from Europe to Mexico, where it is still played today. And when our well-heeled ideas of musical culture encounter the transcultural frames of reference of our colleagues at the IAI, it should be quite exciting.

Restle: At the Kulturforum, our thinking ought to be more strategic and not fragmented. Anyone who is planning an exhibition ought to involve the other collections and archives and libraries from the start. I am confident that we will manage to achieve this within the Foundation.

Do you also have a dream, Mr. Ertelt?

Ertelt: You bet! I would like us to be clearly visible in the cityscape as part of the Kulturforum. When you come here at the moment, you see a nice beech hedge and, behind it, a very useful but ugly parking lot. I would like it all to be removed so that when people pass by in the evening, perhaps on their way to a concert in the Philharmonie, they notice that there is something to discover here.