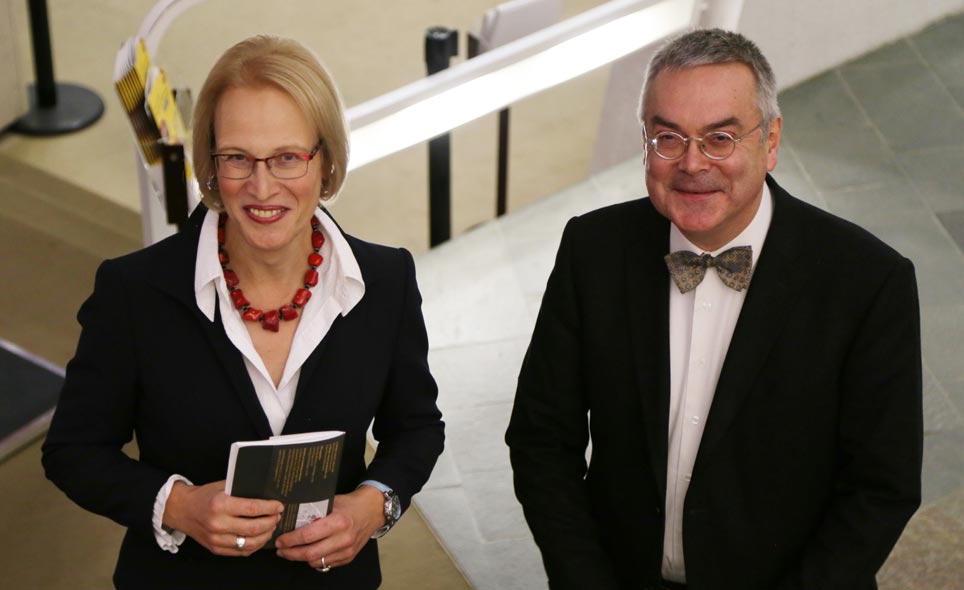

At a recent international museum conference in Rio de Janeiro, participants discussed some very topical issues: the future of collecting institutions, changing global networks and the importance of cultural exchange. The event was attended by Tina Brüderlin, head of the Ethnologisches Museum, and Barbara Göbel, director of the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut.

As the National Museum of Brazil continues to rebuild following the catastrophic fire there in 2018, the two of you recently took part in an international museum conference organized by the German Foreign Office, the Goethe Institute and the Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro. What was the conference about, and what was your role?

Barbara Göbel (BG): The conference was initially meant to expand cooperation between German collecting institutions and the Museu Nacional of the Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. It was part of an aid package offered to the museum by the German Foreign Office soon after the devastating fire, comprising financial assistance for recovery measures and reconstruction. But the scope of the conference ended up going far beyond the Museu Nacional and Brazil, because the focus had expanded to include networks in Latin America generally. On the German side, the local organizer was the Goethe Institute in Rio de Janeiro. From the very beginning, I took part in the planning on behalf of the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut (Ibero-American Institute), because we have had contacts with the Museu Nacional for a long time, and those have intensified in recent years with the cooperative projects run by the IAI and the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum) (EM/SMB). It was important for me to participate for another reason, however, which is that in these times of crisis in Germany, regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean tend to get lost from view. And in that context, it is always important for a bridging institution like the IAI to make it clear how important, diverse, and close the cultural and academic relations are between Germany and Brazil, and with Latin America and the Caribbean generally. Besides that, I personally was very upset by the fire in 2018 because, like Tina Brüderlin, I first got to know the museum as a child. So I have personal memories connected with the Museu Nacional, and I know from personal experience how important it is to other countries in the region.

Museu Nacional in Rio de Janeiro. Foto: CC BY-SA 3.0

Tina Brüderlin (TB): As the new director of the Ethnologisches Museum, I was invited by the Foreign Office and the Goethe Institute to take part in the conference and the discussions with the Museu Nacional as a representative of the Ethnologisches Museum – an invitation that I was happy to accept. The Ethnologisches Museum has been working with the Museu Nacional for many years now, and after the fire in 2018, we helped and provided support together with the Foreign Office. But I wasn’t alone, of course – my colleague Lena Steffens from the Ethnologisches Museum was there too. She presented a collaborative research project with the Museu Nacional that focuses on the historical collections of the Ethnologisches Museum from the Amazon region. That has been running for several years now. The project has to do with historical connections and networks among the institutions and with the importance of historical collections, especially their importance in the present day for representatives of the societies of origin. Andrea Scholz, too, was took part in the conference – at least virtually – along with her project partner Thiago da Costa Oliviera, and together with Barbara Göbel she presented their joint project.

Both of you are very deeply involved in Latin American subjects – did the conference produce any new insights for you? What did you take away from it?

TB: For me, the conference called to mind once again the fact that the many and varied discussions about what a museum can or should do, and what the future of historically evolved collections could look like, are actually part of a global discussion. These questions occupy us here in Berlin or Germany, but it isn’t just us; they affect all countries and communities. In this context, it was very exciting to see how people are thinking about the Museu Nacional at the moment, which lost more than 80 percent of its collections in the fire and is now to be rebuilt in a few years. How can we rethink what a museum is; how are museum professionals in Brazil working with the local communities? It was very refreshing to get away from the European debates for a while, and as someone who is half Brazilian, I naturally have a keen personal interest in the perspectives of our colleagues from Latin America.

In relation to the conference, there are actually two issues that arise: one is the question about the role of museums, which is evidently something that currently preoccupies many institutions around the world. The other is the question of how we treat one another in a global setting, the so-called “Global North” and the “Global South.” Do you consider these questions to be directly related, or are they actually two separate issues?

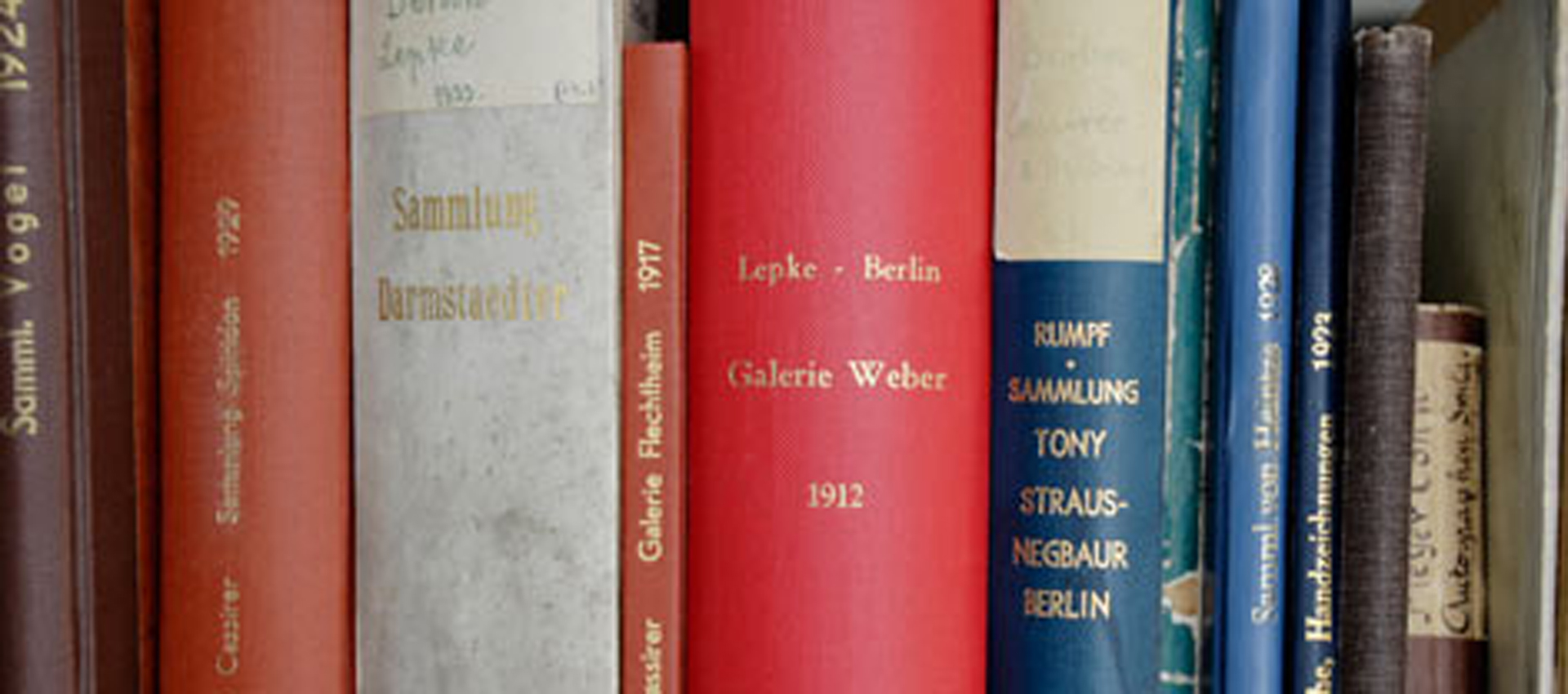

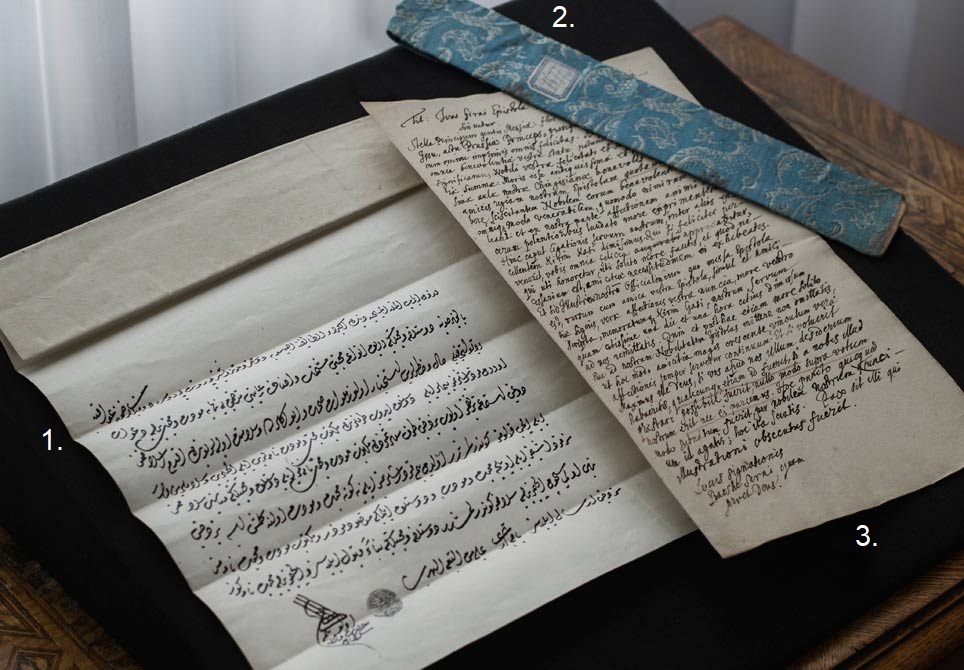

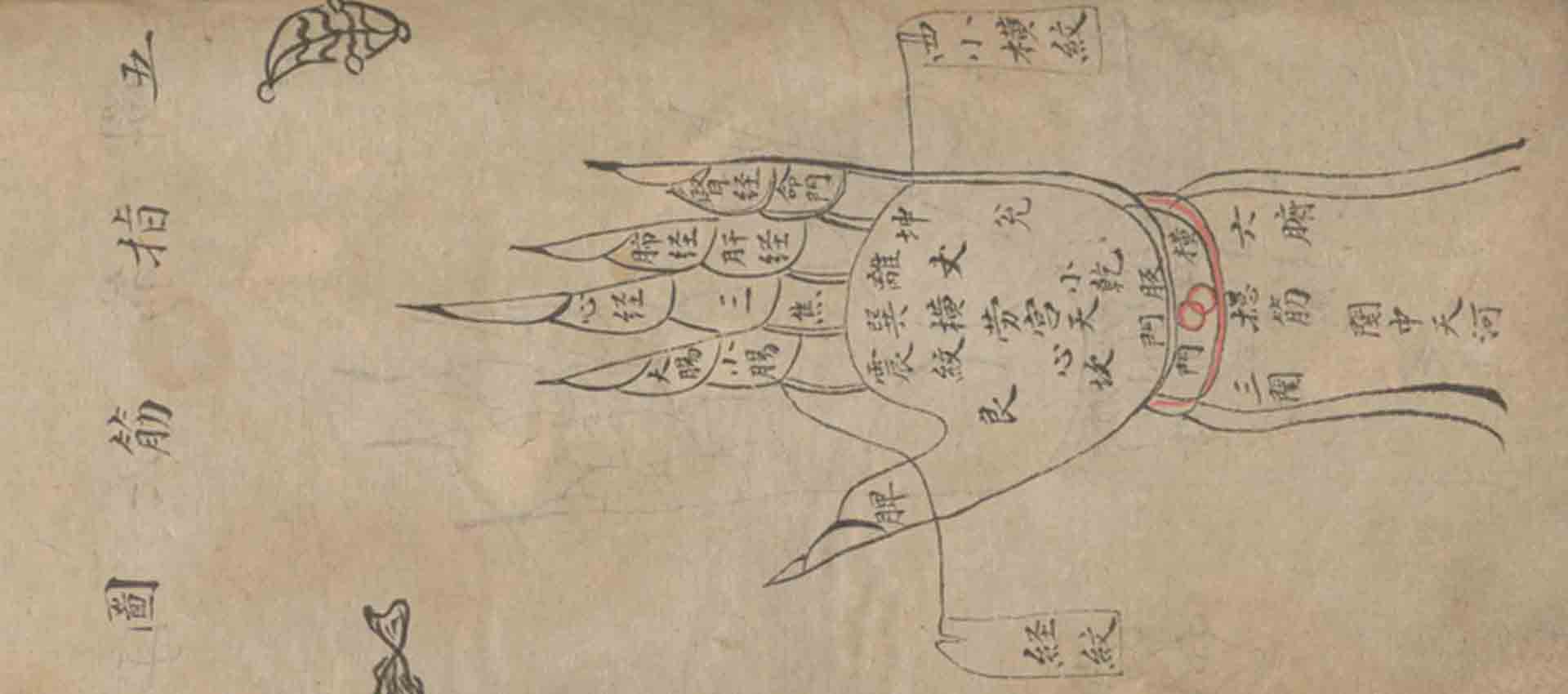

BG: I prefer to talk more generally about collecting institutions rather than just museums, because the discussion affects libraries and archives too, and we should try to move beyond these historically evolved distinctions in the present context of global transformation. From the perspective of Latin America and the Caribbean, the debate about these collecting institutions in a global context is also a debate about interlinked relations that are characterized by structural inequalities. In comparison with Africa and Asia, Latin America has a long tradition of museums, libraries and archives, which is closely connected with the development of the nation states. For a long time, collections and collecting institutions there have also been a focus of conflicts over the recognition and participation of indigenous and Afro-American groups. The great majority of Latin American countries ratified the international agreement ILO 169 – on the protection of indigenous groups – decades ago, so special rights for indigenous and Afro-American groups are enshrined in their constitutions; Germany signed the agreement at the end of 2021. That means there are discussions about pluralistic knowledge practices, cultural heritage, rights to collections and appropriate ways to raise awareness of them – and we in Germany can learn a great deal from these discussions. That was something else that became clear at the conference, as well as the extent to which a variety of perspectives are embedded in these discourses. The conference brought together a wide range of different stakeholders for a productive exchange of ideas and views: representatives of both large and small collecting institutions, intermediary institutions, NGOs, and indigenous organizations. All of this leads to the last and, for me, central point, which defines our day-to-day work at the Ethnologisches Museum and the IAI: the responsibility that we have to our collections in a global context. This includes establishing connections among collections at the international level, ensuring accessibility, and making things visible; the conference was important for those things, too. Our collections are much better known than we think – whether in Tierra del Fuego, Patagonia, Mexico, or Colombia. And in that, there lies an opportunity to engage with the “Global South” in different formats of exchange and different cooperative endeavors that take account of other perspectives on the objects in such a way as to exert a lasting change on our institutions.

When you talk about making things visible, do you specifically mean raising the visibility of the cultural heritage of Latin America and the Caribbean in Germany?

BG: Yes, that is an important topic for us at the IAI, and we are working very hard on that, despite the difficult financial circumstances and a shortage of personnel. One way in which we are doing it is to publish our website in four languages, so as to make it easier for people to access information, items from the collection, and publications. We are digitizing our holdings to the best of our ability, and we are pursuing a free, open-access strategy with our publication program in four languages, so that access to the collections and collection-based publications of the IAI is possible in Latin America and the Caribbean, too. The conference in Rio impressed upon me once more how important it is to keep working on this, despite the difficulties. That also means that we must address the challenges of digital exclusion and include content that works without good internet infrastructure, be it in the rural regions of the Amazon or in parts of eastern Germany.

TB: That was something that came across very clearly for me as well during the conference: exclusion and access is a central issue. A number of times, people that I spoke with commented on the collections held in Berlin. There is quite a lot of interest in working with them. For example, the Ethnologisches Museum has an archive with one-of-a-kind historical audio recordings of indigenous people from the Amazon region, and their representatives know very well that these are in Berlin. They are quite well-informed on the topic and are very interested in working with this material there in Brazil. This shows how essential it is that there be access to these repositories of cultural heritage, and why enabling such access remains one of the constant goals of the EM.

Have global networks changed in recent years?

TB: Global networks are essential, and they’ve been around ever since our institutions were founded. That lies in the nature of the institutions involved, since they work with worldwide subjects and collections. Technical progress and the new media are enabling new forms of exchange today, but at the same time, we shouldn’t think that the digitization of collections and holdings solves all of the problems of accessibility. Digitizing content and creating transparency around that is a crucially important step. It allows collections to be used by a variety of people with a wide range of interests in different places around the world. But not everyone has access to the requisite technology. We should always keep that in mind. The physical collections remain relevant. Given that, digitization can be a first step in getting to know the objects that are held in the collections.

What should be done, in your view, to make your institutions ready to meet this challenge? After all, a collecting institution can’t go laying fiber-optic internet cables somewhere; so what can they do?

BG: There are, of course, structural inequalities, infrastructural borders and financial bottlenecks over which we have no influence. But we can set the threshold low and do things without major technical effort or expense. With a view to “quick and dirty” solutions, in other words. What is doable and moves us forward quickly? Communicating the information on Latin American and Caribbean collections in an interconnected form, enabling access to them from different disciplines – that is an important aspect of our cooperative work with the Ethnologisches Museum and with other SPK institutions. In general, this is a central goal of the current reform process at the SPK. The cooperation between the IAI and the Ethnologisches Museum can bring great benefits to both of us, and together we can raise the profiles of both institutions. We do have complementary collections for Latin America and the Caribbean, and increasingly, we would like to educate audiences about these collections in a transregional context. And that is why one important goal of the conference in Rio was to strengthen the joint strategic partnership with the Museu Nacional. With its important postgraduate programs in the fields of biology and in social and cultural anthropology, the Museu Nacional is an important relay of knowledge production in the Latin American context. And the Goethe Institute likewise has a strong network in the region. We need these strategic partnerships for our work in the regions concerned – because they create the networks of trust and the spaces for interaction and exchange without which our collections have no future.

TB: There are some efforts already underway in the field of digitization, and much has been achieved already. But there are so many more exciting things to be done that go beyond that, starting with multilingualism and including things like knowledge categories, pluralistic forms of knowledge, and the transmission of knowledge in databases. All of these things take place in technical and organizational processes that are very elaborate but mostly occur behind the scenes. At the same time, museums are usually measured with reference to the visible part of their work – the exhibitions. But this is exactly where everything is intertwined, because the collections are the backbone that gives rise to everything else, on which we work with partners in many different international projects. And there are wonderful things we can do there, when we can cooperate with partners worldwide and together think about how knowledge can be presented or conveyed, and ask what terms, what images and what language should be used for that? That is an incredibly rich range of possibilities, on which there is still a lot of work to be done, but it can lead to very exciting results.

What is the nature of this “invisible” work that takes place outside the limelight of the large exhibition projects?

BG: We want to create connections between objects and people, be they researchers, creators of culture such as artists and authors, or indigenous experts, because it is these people – who have a genuine interest in the objects and have knowledge about them and their role in society – who increase the reach of our collections and holdings. These are mediators who have extensive networks in the regions from which they come. For the IAI, some very important examples in this regard are the eighty or so visiting academics who pursue their research at the institute each year with a variety of grants (scholarship program, DAAD, AvH, Conicet, Conacyt, Capes, etc.). A number of them also pursue research in the Ethnologisches Museum, so we play host to them together and link our collections that way. Increasingly, the Dahlem Research Campus of the SPK, with its events, exhibitions and joint externally-funded projects, is also becoming an important complementary space for the IAI for exchanges regarding material and non-material cultures in the transregional context.

TB: At the Ethnologisches Museum and the Dahlem Research Campus, we organize residencies that are filled by researchers as well as artists and people from a variety of contexts. We want to and we must expand these collaborations so as to make sure that critical examinations of the collections are always possible.

Ms. Brüderlin, you’ve just said that everyone always looks at the exhibitions, because those are what is most visible from the outside. But these exhibitions are, of course, the most important tool for educating the public about the networks and knowledge you described and for translating them from the academic context. How do you approach this challenge? How can that be done?

TB: I think we are doing that already, as many exhibitions – at least in ethnological museums – are based on networks, exchange and insights that the museum staff have built up around the collections together with partners from the societies of origin. The goal is to elaborate the narrative arising from the objects and the relevance of the collections – historically and in the present day – and to find new ways to convey these things to a broad audience. That is an integral part of ethnological work. So we are quite pleased that in September, when the last exhibition spaces of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst (Museum für Asiatische Kunst) and the Ethnologisches Museum are due to open in the Humboldt Forum, many of our international partners will be coming to Berlin to join us in celebrating the opening of the exhibitions. There will be over seventy guests from many different corners of the world who worked with the museums on the exhibitions.

BG: I think in the future, we have to put a greater focus on the process and free ourselves from the one-sided fixation on certain products – be they exhibitions or publications. The SPK is a cultural institution and a place where scholarship is pursued, and that is what makes it so unique and interesting – and interesting as a space for raising many different social issues, too. When we focus on the process, the openness and the incompleteness, then we soon see that it’s not a question of either-or but rather this-as-well-as-that. That means addressing all of the stages at which knowledge is generated, and taking account of different forms of knowledge and knowledge practices, as well as tolerating disruption and dissonance. These complex processes are always multi-institutional, multi-disciplinary and international in outlook, and we face the constant challenge of bringing various stakeholders with various perspectives, experiences, and interests together into a productive exchange on as equal a footing as possible. But orchestrating these very processes is just what we are made for at the IAI, given our profile and our expertise.