People who visit cultural institutions or use their services have become choosy, but can every place really do everything? We met Christina Haak, the deputy director general of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin), in her office together with entrepreneur and service designer Nancy Birkhölzer, the director of the Geheimes Staatsarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Secret State Archives) Ulrike Höroldt, and cultural scholar Wolfgang Ullrich for a conversation that ranged from Wi-Fi in the reading room and simpler language in exhibition rooms to stories for Instagram and whether David Bowie comes across better than Mark Rothko.

Ms. Birkhölzer, what does a service designer actually do?

Nancy Birkhölzer: People use services every day, often without being aware of them. For example, the procedures in a hospital: What intentions do I enter the hospital with? What needs do I have? Am I a patient, a visitor, a doctor, etcetera? How are the different needs of these "users" met? Where do people perform certain steps as part of a service process, where are there control systems, physical products, or digital services? All this, the experience that a “user” has in a hospital – or more generally with a business or a brand – is tailored in detail by service designers in order to ensure the best possible experience. Service design processes can be applied as much to a hospital as to a services company – or even a museum.

The user experience begins long before the moment when I enter a museum: How do I come to hear about a museum or an exhibition? Can I buy the ticket online, in advance? How do I get there? Do I have to queue at the entrance? Where can I drop off my coat and bag? Every detail is relevant to the overall user experience, which will hopefully be remembered as a positive one.

And what has been your experience of the SPK and its museums?

Birkhölzer: None. I couldn't tell you which institutions belong to the SPK and which do not. My perception of the SPK brand is basically non-existent. Of course, I do notice what exhibitions are being held.

If the subject of the exhibition interests me, then the museum where I go to see it is of secondary importance. Unless, that is, the museum is worth seeing from an architectural point of view and is therefore the trigger for the visit. Often, however, it can be the situation (when it's raining, or I have a few hours of free time, etcetera) that gives me the idea of going to a museum spontaneously, and then I'll have a look to see what exhibitions are on at the moment. So there are different needs that trigger a museum visit – and in the best case, they are satisfied. So it is important to analyze and understand these needs – and user behavior – in detail.

Wolfgang Ullrich: You could also ask: which collection do I want to see again? Nowadays, permanent collections are generally not a sufficient reason to go to a museum. A particular reason is needed as well, like an exhibition.

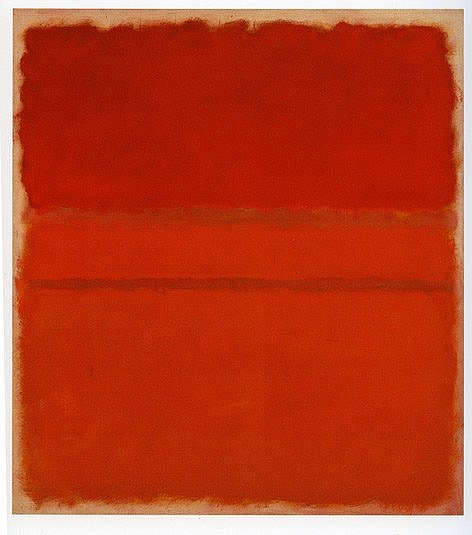

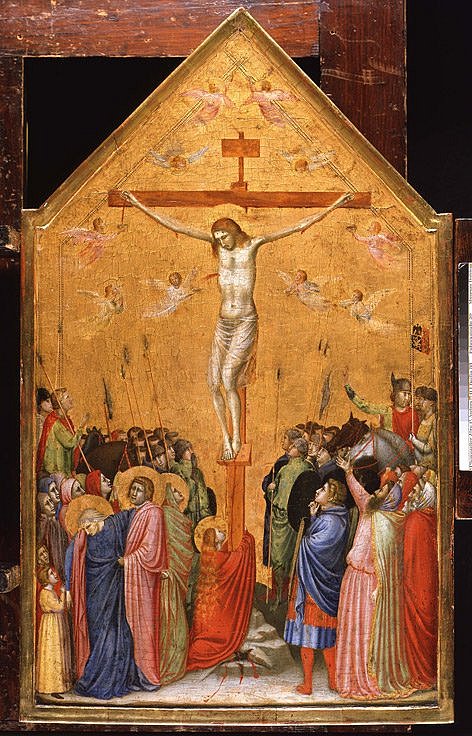

Christina Haak: I believe that our permanent presentations must, in principle, also have a degree of flexibility. Sometimes small-scale changes are enough, such as when we put Mark Rothko alongside Giotto in the Gemäldegalerie (Old Master Paintings).

Birkhölzer: Recommendations often induce people to visit a museum. For example, I have just been recommended to visit the Geheimes Staatsarchiv… well, the Secret State Archives, that sounds great, for a start. It arouses my interest and I want to find out more.

Ulrike Höroldt: The “secret” bit is a nice old title that we've kept from olden days. It's nothing to do with secrets as such, more with confidentiality, because the archive originally held records for the Privy Council: people who the king or emperor appointed to advise him. We are not an exhibition venue. We do usually have a small display in the corridors in front of the study room, but that is only an incidental feature and the space is rather cramped. Our main purpose is to make the archive materials available for research. As a rule, people don't come to us because it's raining, but because they have a special topic that they are interested in and want to do research into. And for the average person, that usually means family history. This is a very widespread field of interest and it is becoming even more widespread in the digital age, because people feel the urge to know the facts of their own history. Apart from that, our users are mostly scholars researching a wide variety of subjects connected with Prussian history.

Mr. Ullrich, you have said that a museum should be a “creativity agency for gaining experience.” What would that mean for the museum of the future?

Ullrich: I coined that term with the past in mind, as a way of describing the paradigm shift that has taken place over the past few decades. For a long time, museums were closely analogous to archives. They were visited by people who needed them for a specific research topic, or who wanted just to work with the objects in the collection in some way, and they gradually developed into something that also felt responsible for a wider section of the public: for tourism, for families, etcetera.

The situation today is that many people no longer go to a museum or an exhibition out of some kind of civic duty to educate themselves, nor because they want to admire the great geniuses of art history. They go because they want to be inspired, they want to mobilize their own slumbering potential. They want to be enriched and come home from the museum having had their self-awareness positively stimulated. Hence my use of the term “agency,” or the idea of a “service provider.”

Just as you would expect to be freshened up all-round at a wellness hotel, in order to deal with daily life better, so you would expect something similar from a museum. Not exactly the same thing, of course, but there is nonetheless a degree of competition in that area. The expectations that people have of museums and exhibition venues don't come out of nowhere – all the publicity for art shows implies that the museum is a place that can "help" each target group and each person individually. I believe that this trend will continue to grow and will differentiate.

I am sometimes skeptical whether all museums and exhibition venues should be subjected to this paradigm. I see the museum in general as an institution that is already strained or overstretched. It has been burdened with more and more tasks in the last few decades without the addition of funds or personnel to match. And for that reason alone, the pragmatic question arises at some point: can every institution do everything now?

This summer, Jürgen Kaube, co-editor of the FAZ, said in a lecture on the Museumsinsel (Museum Island) that museums are unable to cope, now that they are supposed to respond to everything: to the migration debate, to German colonialism, and even to #MeToo. So are museums really overstretched?

Haak: To start with, it is basically positive that we are trusted to do all this and that we are treated a bit like a cure for all ills. You start to become overstretched when you don't have enough resources. We can do a lot, and if we define ourselves as an alternative arena for social debate, then we also have something to contribute in many areas. That will increase over the next ten years. Every museum has to ask itself the question: what do I stand for?

I am sometimes skeptical whether all museums and exhibition venues should be subjected to this paradigm. I see the museum in general as an institution that is already strained or overstretched. It has been burdened with more and more tasks in the last few decades without the addition of funds or personnel to match. And for that reason alone, the pragmatic question arises at some point: can every institution do everything now?

This summer, Jürgen Kaube, co-editor of the FAZ, said in a lecture on the Museumsinsel (Museum Island) that museums are unable to cope, now that they are supposed to respond to everything: to the migration debate, to German colonialism, and even to #MeToo. So are museums really overstretched?

Haak: To start with, it is basically positive that we are trusted to do all this and that we are treated a bit like a cure for all ills. You start to become overstretched when you don't have enough resources. We can do a lot, and if we define ourselves as an alternative arena for social debate, then we also have something to contribute in many areas. That will increase over the next ten years. Every museum has to ask itself the question: what do I stand for?

Ullrich: For about fifty years, there has been discussion about whether the museum has this central function in society. After 1968, people went on and on about the open museum: open in the sense that it is a point of contact for many different sections of the population. If you count how many people go to the museum today – well, it may not have worked out. "Culture for all" is still a completely illusory concept, but much has changed nevertheless. At the end of the 1960s, people were asked what they associated with the term “museum”, and they gave answers like “musty,” “gray,” and “empty” – all words that nobody would associate with museums today. Apart from somebody who hasn't been to one for fifty years, perhaps.

One reason why that has changed is that an extremely large number of new museums and exhibition venues for contemporary art have been created during the past few decades. These institutions have to take on other tasks; they have to try to reach out into society and address political, social, and other issues, otherwise they very quickly lose their legitimacy and really do stand empty. Do the forms of presentation in exhibitions and in museums live up to what you described as a “wellness center”? While being academically correct in our exhibitions, are we sometimes too straight-laced?

Birkhölzer: Art education, as a generic concept, cannot satisfy any specific user needs.

Haak: We have a relatively large project in the digital sphere: museum4punkt0, which we are running nationwide in partnership with five other museums. The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin are working on a digital visitor journey. It's basically what you mentioned, from the physical point of view, earlier: I come to the museum, but what do I experience beforehand, and what in the place itself, and what can I research afterwards if I want to?

In other words, what do our visitors need in order to be able to get the most out of their museum visit? We discovered that we lacked an adequate basis for considering the question. So first we had to decide how we could end up with sufficiently robust conclusions. Who are our visitors and what do they need for the museum visit to be a positive experience? Otherwise, we would have developed something and only afterwards would we have asked who wanted it and who was using it. We then decided to use what are known as motivation types, which we analyzed and asked specific questions of. I mean "motivation types" in the sense of “why does someone go to a museum?”

Birkhölzer: What you are saying is certainly the right way to understand the motivation of visitors and – more importantly – of people who you have not been able to persuade to come to the museum before.

Today, it is no longer enough to design beautiful surfaces or rooms. Aesthetics and design are often seen as superficial factors that may be beautiful, but are not effective. It is more productive to design in a user-centered way and to observe the people who I am designing for closely. And there I am with you, Mr. Ullrich: not every museum can serve every purpose. As a user, however, I would like to have the opportunity of finding out where the main focus of a museum lies: Where can I learn something about the context and the artist, where can I do research into specific questions, where are children welcome, where can I gain inspiration, where can I find impressive architecture, where do I just let the art soak in, etcetera? And then, depending on what I want, I decide where to go.

Ms. Höroldt, what do you know about your users?

Höroldt: As a rule, we know the subject of their interest and what they want, as they often write to ask us in advance, or describe their needs to us in a personal consultation in the study room. For example, we know that around 85 percent of personal use in 2017 was of a scholarly nature, around 10 percent related to family history or local history, and the few remaining percent had an official or business background.

We have also seen something of a decrease in use on-site. This has to do with the fact that today it is no longer necessary to examine the papers in our reading room for every question, because users can request digitization on demand. Many of them also receive the file that they order from our website as a reproduction at the same time. Our primary goal is not to generate more and more users; instead, we are more concerned with offering our users the services that they really need. Quite often our sources are handwritten and that means they are more or less difficult to read; also, many people are a little unsure of how to use an archive. That's why we provide our "Introduction to Archive Use".

People who want to know how the archive works are taught how to use the finding aids, which are already available electronically in many cases, but are still analog in others, and they learn how to approach archival research.

And now that you are changing your terms of use, Ms. Höroldt, do they include what you have just described?

Höroldt: Since the beginning of 2018, we have allowed users of our reading room to take photos of the files themselves, using their cell phone, tablet, or camera. That was once frowned upon in archives. It too is a paradigm shift, if you will. We introduced it as a pilot project on January 1, 2018 – but at the time, our terms of use still said something completely different. Now we have changed them, as of January 1, 2019, and tried to make access even easier. In particular, we've freed users working on site from the shackles of rules that are outdated or no longer necessary. The application forms have been simplified, you can take photos yourself, we have Wi-Fi in the reading room, and we have abolished the requirement that anyone who wants to re-use one of our reproductions has to ask for permission to do so in each case.

Haak: At some point, we too lifted our prohibition on photography for private use – with the exception of Nefertiti – because it was too much of a burden and a strain on everyone. It's stressful for our attendants too, if they are constantly having to take a tough line with visitors in order to prevent photos, which furthermore doesn't leave a very positive impression. Nobody wants "no photographs!" to be shouted at them across the room; after all, a visit is supposed to be a pleasant experience.

We have kept the ban in place in the Nefertiti room because it is nicer for the visitors themselves that way. It’s a known fact that they prefer to enjoy the moment with the exhibit without the constant clicking and flashing of cameras.

Birkhölzer: Yes, these are the little things that improve the user experience. Another big subject is the preparation of the content. The feeling is often given that the content is made by experts for experts. Of course, I can just look at art and say to myself: Do I like this? Does it speak to me? But there are many scenarios I would like to understand: What time was it created in? What was happening politically at this time? What are the connections? What effect did it have on art history? What stage of development was the artist going through? In my opinion, too little is offered in this regard for people's various degrees of knowledge.

Ullrich: I think that a lot is actually explained, for example with audio guides or guided tours.

Haak: But it depends on the topic or genre. Technology museums, natural history museums, and museums of cultural history usually have an easier job of communicating their content – with pure art there is often little that can be done with presentation tools. Well, perhaps it depends on what you believe in. You can integrate different perspectives there nevertheless, but it is more difficult. There, too, you have to start from types of motivation. What do the classic visitors to an art museum expect and what can they cope with? If I were to say okay, now we are going to do that for the entire permanent exhibition, then I would need a lot of funding and resources. It doesn't mean that we haven't made a start. In the Ägyptisches Museum (Egyptian Museum), for example, we have added an “Easy Language” option to the audio guide. But that is only the beginning of the internal consultations: a professional linguist has to reformulate the scholars' texts in Simple German. When these go back to the authors for review, it can easily happen that you spend hours discussing the best substitute word for "display case." On the other hand, it means that we just have to relinquish some of our sovereignty over interpretation.

Höroldt: It's often like that with archivists too: we start from our own viewpoint and tell the something users about ourselves, but nobody benefits from a highly complex text that hardly anyone from outside understands. We have to learn a way of speaking – that needn't mean Easy Language right away – that is on the same wavelength as the users. This actually applies to all such services. We have to move away from cerebral – and very bureaucratic – language towards a style of language that people feel comfortable with. Of course, limits are set for us in the case of some mandatory legal texts, such as those concerning data privacy.

Ms. Haak, 2018 was a summer of discontent for the museums. There was a lot of pressure, and heavy criticism with regard to the program and the dwindling number of visitors. Is the solution really just to open a David Bowie blockbuster exhibition every week?

Haak: I would like to have both: David Bowie and the concentrated Giotto/Rothko experience. With blockbusters you can still create a high-quality experience, and the content certainly doesn't have to fall by the wayside just because it's a blockbuster. We aren't purely exhibition venues anyway; we always produce them around a core of work from the collections.

The criticism was that there had been beautiful chamber concerts, but the great symphony was missing.

Haak: Beethoven wrote nine symphonies. So to that I would say: symphonies are masterpieces, and even we don't deliver three of those each year – for financial reasons alone. And in that case, it's fine to have the chamber concert in between, which has its own value as an experience and is also appreciated by the public.

How did the debate about the Berlin museums appear to you, Mr. Ullrich?

Ullrich: When I go to the Bode Museum, I often wonder why there aren't many more visitors. On the other hand, I am very glad to have the space to myself, because that is a very special museum experience. I think it's a shame when museums are measured only by the number of visitors. In the 1970s, hardly any museum director knew the figures for that. In the meantime, you expect to have to provide information about it on a daily basis, instead of being judged by the new acquisitions you have made or the research that you are doing into the objects in the collection. At some point, it starts to affect the substance of the museum, because it causes the focus to shift in a way that risks neglecting the classic tasks and responsibilities of a museum – things that go under the headings of collecting, preserving, and researching.

Haak: All the things that are essential if you want to be able to produce an exhibition.

Birkhölzer: With so much on offer, isn't Berlin a place where you have to engage with people more pro-actively? I have an annual museum pass and I often think: where shall I begin and what shouldn't I miss? I would like to see more introductory input, or curation, from the experts. Overviews of the top museums in various categories: for example, in relation to architecture, or for improving my knowledge of art history, or those with the best exhibitions for children or in a political context, as well as a search function for all of Berlin's museums by subject, etcetera. For me, that too is user-friendliness.

Haak: We have to go where people are: in the digital sphere. Here we need many more distributors for our content, trustworthy channels on the Internet.

How would you like an SPK cosmos to be experienced – in terms of user and visitor friendliness – in the future?

Höroldt: I would like the archive to have the new storage facility within reach at last. At the moment, our user friendliness is reduced by the fact that we have to fetch three quarters of our archive material from storage in Dahlem, miles away on the other side of town. It would also be nice if we could get a multipurpose room as part of this construction project, in which we could present exhibitions and hold conferences or other events. Many archives have such facilities nowadays.

Ullrich: Many visitors measure the success of their museum visit by whether they can create stories for Instagram or feed their social networks – but then problems with image rights quickly arise: What am I allowed to do and what not? The Kunsthalle Mannheim has recently launched an interesting pilot project with VG Bild-Kunst [the body that administers picture rights payments], which I would like to see all museums operating within ten years. The institutions pay a flat rate for the image rights and can thus offer their visitors a guarantee that works under copyright can legally be posted in social media. That would make museums more attractive, especially for many young visitors, and would offer completely different possibilities for conversations about works, about art in general, and about museums.

Haak: My main point would be that certain things don't have to contradict each other, that we can stand for "Prussia" and "quality", and at the same time say: "We are nonetheless cool and have a lot to offer." And that together we can convey what we have to offer better to women and men. And that the SPK shows itself in all its colorful diversity, which definitely sets us apart.

Birkhölzer: My wish is that you to manage to arouse a great many people's curiosity about what you have to offer. And that you understand the needs of your visitors and meet them so well that they enthusiastically recommend visiting you.