The KUNSTASYL project tells people's stories of life as a refugee. Now you can find out about them in the Museum Europäischer Kulturen.

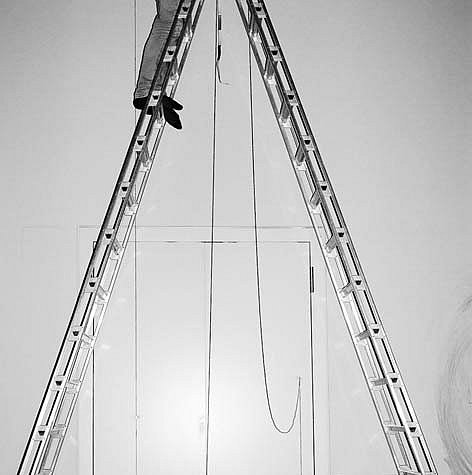

Afghanistan. Pakistan. Iran. Iraq. Turkey. Greece. Macedonia. Serbia. Hungary. Austria. Liechtenstein. Switzerland. France. Belgium. Germany. Jasim is standing in the Museum Europäischer Kulturen (Museum of European Cultures) in Berlin-Dahlem, painting the route of his odyssey across the Middle East and Europe on a wall. He has crossed fifteen countries, walking almost all the way - and always at night. During the daytime he hid, waiting until darkness fell and he could continue on his way. At times on the journey, Jasim says, he had nothing to eat for days, nor could he sleep.

Today, one of the other walls – the wall near Yasir's bed – is going to be painted. The thirty-year-old from Iraq wants something colorful to rest his eyes on and refresh his spirit. Looking at off-white, slightly dingy walls, it is easy to understand his wish. The impersonal nature of the furniture, the random layout of the room – how are people supposed to feel at home here, or become attached to new memories? The resulting emotional vacuum leaves plenty of space for the ghosts of the past to re-emerge.

His life is one long list of countries that did not want him – not even his own country. He was born out of wedlock in Afghanistan, so his mother first sent him to Pakistan for four years. This was done for his own protection, he explains, because in the country of his birth, he would have been despised as "ibn Haram": fatherless. He would have had no rights and would have been excluded from any social community. In Afghanistan, an illegitimate child brings shame on the mother and on the family as a whole.

For Jasim, this ostracism meant that he could never play with other children, never visit a mosque, and was kept at arm's length on the fringe of society. Jasim speaks in a quiet voice, often gazing at his hands. You have to make an effort to understand what he is saying. His age is hard to estimate: he could be 35 years old, or perhaps 45. In fact, Jasim is 31.

The perilous journey, the uncertainty, and the wait for official approval have made him old before his time, he says, and points at himself. The hair at his temples is turning grey; the experiences of the last five years have engraved lines in his face. He finds it hard to sleep and is already wide awake at four o'clock in the morning, even now that he is in Germany. Much stress, he says, by which he means the psychological burden of an existence without a firm foundation, without the security of being able to stay in one place.

Home, for Jasim, means his family and his country. Despite this, he does not want to return. Afghanistan is trapped in the past and is moving further backward every day, he explains. Children are not permitted to learn reading and writing, and schools are being closed down. The Taliban rule secretly even in places where they are not officially in power, and they take drastic action against anything that they consider too secular. Afghanistan is a deeply unjust country, he continues, and with broad segments of the population being denied education, that will not change in the foreseeable future. A country on the way back to the past, without a future.

Jasim has been in Germany since January 2015. Since July he has lived in a hostel for asylum seekers on Staakener Strasse in Spandau, while he waits for his application to be considered. The building stands at the border to an industrial zone, and in a way it is also at the border to German society. What goes on here could be described as "standardized waiting". About a hundred residents are divided among a number of rooms, each of which contains up to five beds, a small table, chairs, a wardrobe, and a sink. Brown, stained carpeting hints at the building's former use as offices for the local health authority. A German visitor instinctively looks for the machines that dispense numbered tickets for the waiting room. A communal kitchen opens off the corridor, as does the toilet. All this does not give you the feeling that you have arrived somewhere, or have found a space of your own.

Does it really have to be like this? This question got artist Barbara Caveng thinking. So in 2015 she launched the KUNSTASYL project, which means "art asylum". It aims to give people who have had to flee their homes an opportunity to shape the appearance of the place where they are currently living. KUNSTASYL is neither occupational therapy nor art therapy. The project is rather conceived as a platform for generating opportunities through the exchange of ideas among its participants, as well as improving internal and external communication.

The terms 'refugee' and 'asylum-seeker' are not used on this project. For Caveng and for everyone else involved in the project, this is about people, plain and simple – people who do not deserve to be pigeonholed like this.

Although this may sound vague and merely theoretical at first, it is being put into practice in a very tangible and humorous manner, with a generous dose of openness: on this particular day, Syrians, Albanians, Iraqis, Pakistanis, and Germans are standing crowded together in one of the rooms. The metal bed frames have been stacked on top of each other on one side of the room and the sparse furnishings pushed against the wall.

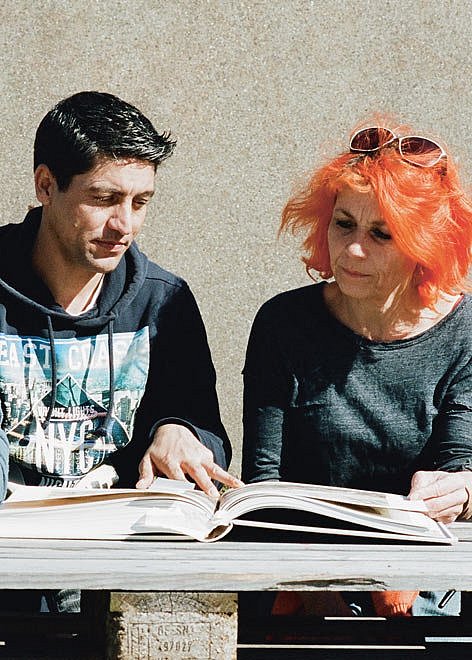

While Yasir mixes the paint with Dachil, Barbara Caveng explains the thinking behind KUNSTASYL. It is not a project "for refugees", but something that arises from working together, from the ideas and inspirations of the people taking part. In any case, the terms "refugee" and "asylum-seeker" are not used on this project. For Caveng and for everyone else involved in the project, this is about people, plain and simple – people who do not deserve to be pigeonholed like this: with labels that distort our impression of the character and, in fact, of every aspect of the person standing in front of us, with terms that exclude displaced people from society.

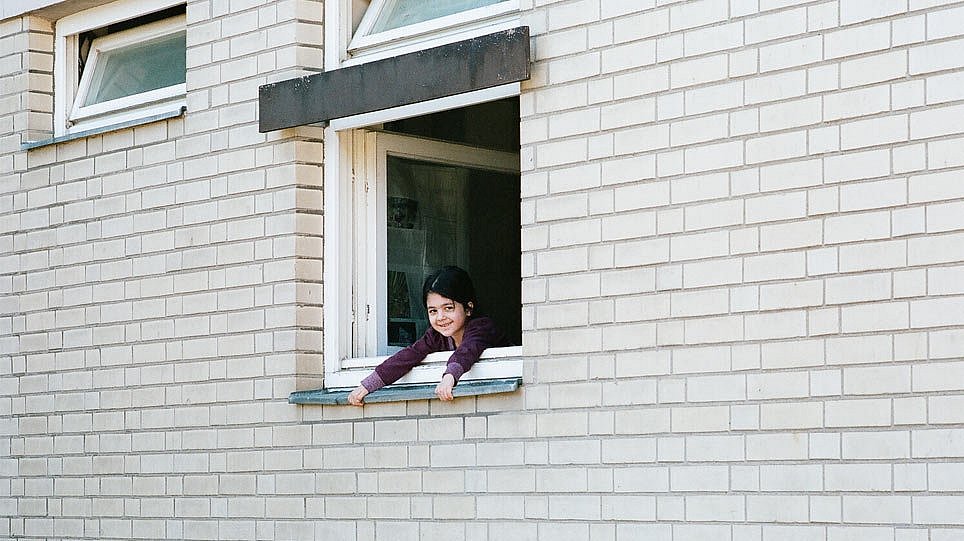

Both the thinking behind KUNSTASYL and its practical implementation are correspondingly free of boundaries. The projects are neither for men only nor women only, nor are they aimed specifically at children or certain religious groups. The activities are open to anyone who wants to join in. They give rise to a global society in miniature, which is explored, practiced, and lived here every day. Indeed, right now people from six different nations and at least four religious communities are working harmoniously together, redecorating the room while children run in and out and, every now and again, somebody opens the door to see how the work is coming along.

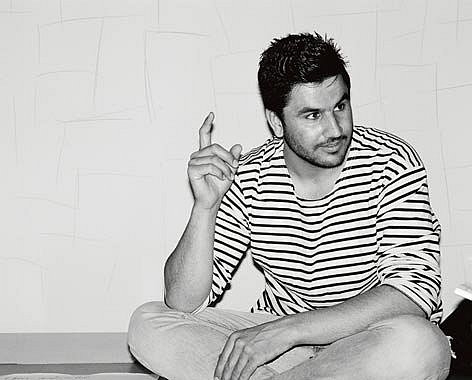

Dachil too can confirm that the idea behind the jointly developed grassroots project works in practice, despite the initial skepticism. The 24-year-old from Sinjar in Iraq has been part of the team from the outset, making a significant contribution to the development of the project. He also designed the KUNSTASYL logo. It shows a man carrying his fingerprint like a heavy boulder on his back: a symbol of the indelible imprints that life leaves on the soul.

Despite these scars, which every inhabitant bears, life together in the hostel has been transformed, he feels, since the KUNSTASYL building site trailer was brought into the yard.

The people here no longer define themselves first and foremost by their place of origin or their faith. Instead, a new identity has grown up, independent of religion and nationality. The residents are proud of what they are doing here. The project has restored their dignity, thinks Dachil, and the freedom of mind to see each person you encounter as a human being, as an individual. "Art has brought people here into contact with each other," he says. Previously, he would not have thought it possible for people to live communally with those who think differently to themselves.

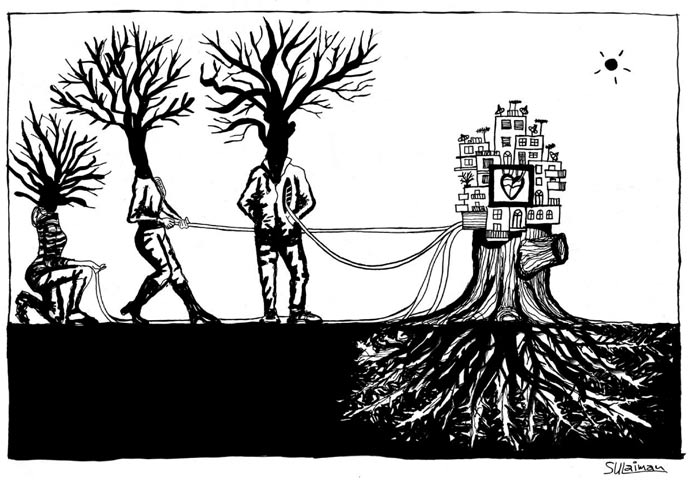

Now KUNSTASYL is reaching out from Spandau to Dahlem. The project has occupied one of the rooms of the Museums Europäischer Kulturen (Museum of European Cultures) in a "friendly takeover" announced by a banner with the thumbprint logo, which hangs at the museum's entrance. In the museum, Jasim is not alone as he paints the route that he travelled to Germany – Dachil and other residents of the hostel in Spandau are busy making their statements as well. The art taking shape on the walls of the room embodies aspirations as well as painful memories. The works are linked by a visual element that they all refer to in some way: the iconic wave by Hokusai, a master of the Japanese woodcut. The wave is a symbol of power and destruction, but also of hope and forward motion. The halls of the museum offer plenty of space for the compositions and thoughts to unfold.

Barbara Caveng considers it "unprecedented" for an institution such as the Museum Europäischer Kulturen "simply to make 500 square meters available so that those who come along can be empowered to act on their own behalf again." This is no mere invitation to be a participant in a paternalistic scheme, or to integrate in the society of the majority with its gracious approval – it is rather an opportunity to display differences and acknowledge them. In other words, a truly self-assured Europe.

Caveng also appreciates the participants' involvement in working out the concept and subsequently developing it into an exhibition. The culmination of their efforts came on 22 July 2016 with the opening of the exhibition "daHEIM: glances into fugitive lives“ exhibition daHEIM – glances into fugitive lives. It sets the newly created drawings and installations in a historical context, which is provided by the stories of refugees in Europe during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

"In all of our activities, we involve visitors or the protagonists themselves. We are going a step further with this project, because it is being implemented completely independently by the people concerned – we, the staff of the museum, are staying in the background, taking responsibility for the administrative and organizational tasks, and helping with the mediation work. The exciting thing about it is that all the people involved are learning an incredible amount from one another." Each person who reaches Germany by one of the many arduous paths has the hope of finding a new life, Dachil believes. People leave their home country for a dream, be it modest or grand.

The project has restored their dignity, thinks Dachil, and the freedom of mind to see each person you encounter as a human being, as an individual.

His own dream could become reality, step by step. He is co-curating the exhibition that is currently taking shape in the museum; through the project he has found an apartment of his own in Neukölln, and in October he will begin studying art in the foundation class at Weissensee academy of art in Berlin. His art is the way ahead for him, even if it is clear to him that it will not be an easy road to travel. Jasim, in contrast, does not know what step to take next after his long journey. He has done everything that Germany requires of him, he says. He has attended courses in the German language, integration, and educational training; he has discussed his case again and again, submitted evidence, and gone to official appointments. He wants to build a new life with his own hands. "I came for the peace, not for the money." If Jasim were not allowed to stay here, then he would not know what to do next, or where he could still go. Europe? He has already crossed that.