"I would like to have a home where I can be both: what I was, and what I have become and will yet become."

When I start to think about the word “home”, the things that come to mind first are usually quite intangible. There are the smells of childhood: a kind of chewing gum that we had in the Soviet era; certain kinds of yarn that were used to knit the sweaters we wore, and the material of the school bench that we sat upon for years. Then there is the mild excitement, the butterflies in the stomach that I felt when my grandmother came to read to me at my bedside, or when my mother laid her cool hand on my forehead when I had a fever.

There are places, too: the view over Tbilisi from the Church of Father David; the flight of steps in Vake Park that leads up to the victory monument and the eternal flame for the soldiers who fell in the Second World War – and which I ran up with my best friend to see who would get there first. There are tastes: tarragon-flavored lemonade and the almond pastries that you could buy in a bakery on Rustaveli Avenue. There is also a certain attitude to things, which seems inborn, still part of me despite the years I have spent studying my culture and my origins, despite all my critical analysis of customs and traditions. Above all, there are experiences, which you accumulate and carry around with you wherever you go, as if in a large sack slung over your shoulder, invisible to other people. But there are also memories of my life in Germany – of particular situations with particular people. The moments in which I have felt relaxed and free, understood and at home.

Twelve years ago, I came to Germany to study. Ever since then, I have lived in Hamburg – and yet when I go back to Tbilisi, the city that I was born in and grew up in, I always say "I'm going home," instinctively, without really thinking. And each time I wonder why I have said it. After all, I live my life in Germany. And most importantly, German is the language that I write in: it defines me through what I do and what I am. My existence is based in this country. I am neither plagued by constant homesickness, nor do I idealize my native land in any way – on the contrary: from a distance, I see the problems in Georgian society even more clearly. So how can it be, then, that I talk of "home" when I am thinking of Georgia? Why don't I feel that the city in which I have lived for so long, and in which I consider myself free and happy, is my home?

Other people's view of you also changes over time: it is no longer self-evident that you belong. And maybe it is this description that best encapsulates what home means for me – much more than a place, a culture, or even a language can ever be, because all those things can be extended, learned, and acquired.

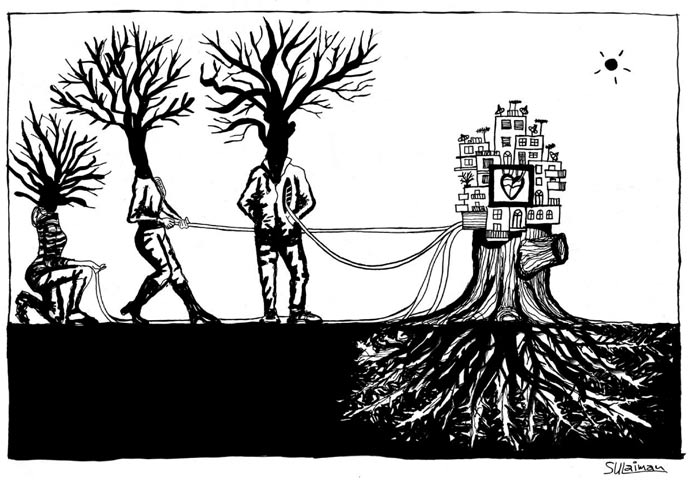

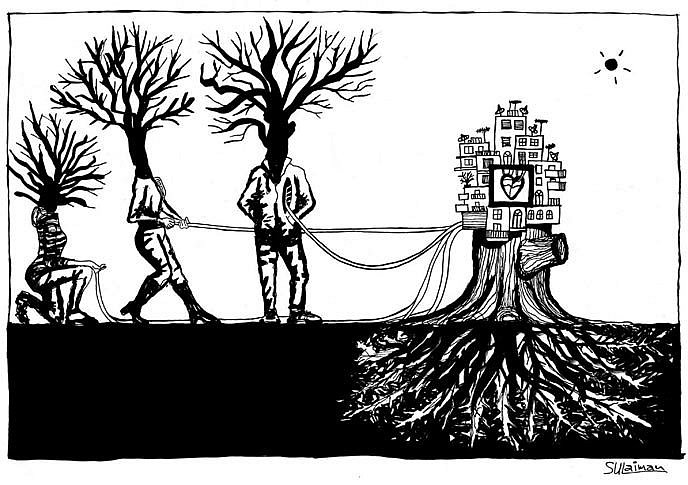

Yes, it is exactly this self-evident quality in your dealings with yourself, with others, and with your surroundings – the small piece of the world that you consider your own. You are simply there, not trying to be anything or anyone. Maybe this feeling of being at home in a place arises, in my case, when things simply are as they are, as a matter of course. When you don't have to call your behavior or your identity into question. And maybe that is the most tragic thing about the loss of this feeling: that everyday life dissolves, that there is no center, only the extremes that you move between. So "home" increasingly becomes an idealized notion, which no longer has roots in daily life.

Nevertheless, it is very important to differentiate between the needs, interests, and motives that lead people to give up the status of naturally belonging. Whether they do it voluntarily or are compelled to. Depending on the context, the decision can be a blessing or a curse. Perhaps many of the people who share my migrant background associate "home" with the country of their parents. Or perhaps that country is just a distant place to them, without everyday connotations. Maybe this sense, this bubble, of not belonging surrounds them neither there nor here.

The distance, the separation, inevitably generate a detachment that makes things appear in a different light. And this light is fairly merciless.

But perhaps they discover – as I eventually did – a certain degree of jester's license, which goes hand in hand with being uprooted: being able to say, do, and think about things differently and innovatively, precisely because you now have a different way of looking at them, precisely because you are always having to ask yourself who you are and where you come from. But how should I, how can I, speak for – or describe the feelings of – people who set out on their journey in danger, under bombardment or small-arms fire, away from their home, away from the place where they belong as a matter of course?

Yet that is exactly what is happening around us every day. People are constantly talking about other people and claiming to know their hardships and fears, claiming to know what is right and what is wrong for them, installing themselves as a mouthpiece. In doing so, they spread prejudices, fears, and above all generalizations, which only polarize opinion and create fronts between groups. There seems to be no middle way to avoid this "either/or" mentality. This division is exactly what I would call the opposite of home.

Migration flows not only say something about the reality of life for those who – for whatever reason – leave home, they also cast light on the society that these people settle in. Billy Wilder, the film director, emigrated from Berlin in 1933, and speaking of his new home, the United States, he said: "Americans get suspicious if you don't want to become one of them – in contrast to the French, English, Swedish and most other peoples, who are made especially suspicious if you do want to belong among them."

I certainly do not want that to change. No, I would like to have a home where I can be both: what I was, and what I have become and will yet become.

What Wilder is describing here is the identity of the United States as a land of immigrants. Even there, the "culture of welcome" has not always been free of tension, but the United States has become home to millions of immigrants nevertheless, because one of its founding principles is to take in people from all over the world. When Wilder talks of distrust being aroused in most European societies if you want to belong in them, he is also confronting us with the question of how we want to define ourselves and our home in the future. And this is a question that we must ask ourselves. It can only be resolved and answered through dialogue: a dialogue that does not exclude moderate opinions and is not dominated by the extremes, a dialogue that allows completely different opinions about to come together as one – because variety does not always represent irreconcilable differences.

Even though most people who ask me which language I dream in look disappointed when I say "in both," that is the truth. In both, depending on the context, the place where my dream is set, and the people who I am talking to in my dream. I certainly do not want that to change. No, I would like to have a home where I can be both: what I was, and what I have become and will yet become. A home in which that does not result in a contradiction. Where it is obvious that we all belong: myself, people like me, and people not like me. Because the native and the foreign merge there into something wholly new. Something that exists as a matter of course, from which a sense of being at home can grow all by itself.