A conversation with Stefan Weber, the Director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst.

Professor Weber, the Museum für Islamische Kunst is internationally active with many of its projects. How did it all come about and why is it important?

These days, foreign cultural policy is about working with other countries, not working in other countries. All of the parties benefit from cooperating on an equal footing – and we have a tradition of doing so that is a good hundred years old. Back in 1914, our founding director, Friedrich Sarre, was involved in building up the Museum of Islamic Art in Istanbul. Cooperation in general has intensified because we live in a different world today. There is no longer a division between "them behind" and "us ahead"; rather the Middle East has long been in Europe and Europe has been even longer in the Middle East.

Syrian Heritage Archive Project (SHAP) with Damage Assessment database

SHAP is a collaborative project of the Museum für Islamische Kunst at the Pergamonmuseum and the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (DAI), funded by the German Federal Foreign Office’s cultural preservation programme. Since its initial phase in the fall of 2013, the project’s primary goal as a task force for the preservation of scholarly documents has been to create a digital archive of Syrian cultural heritage.more

Cooperation with the countries of origin is particularly important because we need to address the fact that we have objects from those countries here and consequently need to do something about these things together. In Syria, we have been working to protect local cultural heritage since 2013, by means of the Syrian Heritage Archive Project and the Damage Assessment Database. The Gulf countries, in contrast, are only just starting to identify and discover their cultural heritage. And we are starting to cooperate with them, for example on exhibitions about views of history.

At the same time we are also working in crisis zones. Two years ago, my deputy, Ute Franke, made a crucial contribution to the opening of a museum in the city of Herat in Afghanistan, by spending a long time there to train museum staff, among other work.

We train restorers and curators here in Berlin too, showing them how to set up databases for object management, or how to prepare exhibition concepts and publications. We are strongly committed to this kind of thing because, among other reasons, many of us have lived and worked for long periods in the countries concerned and therefore have a connection to them.

Some of the key questions facing European society today revolve around the issue of Islam. How does a museum that contains "Islam" in its name deal with this challenge?

Ever since I began studying Islamic art and the Islamic world in general, I have noticed that, in almost every personal encounter, there are a huge number of questions about Islam that owe much to various fears, and much to a poor knowledge of things, and much – above all else – to very clear-cut and simplistic views of culture. And these questions are addressed to us as an institution because – for one thing – more and more people are visiting museums. We alone have had an enormous increase in the number of visitors: up by 80% over the last seven years.

People come wanting answers and wanting knowledge. We have talked a lot to colleagues elsewhere and argued with them, because although many museums of Islamic art are making alterations for this reason, we see that the curators have not worked out any answers to the basic questions.

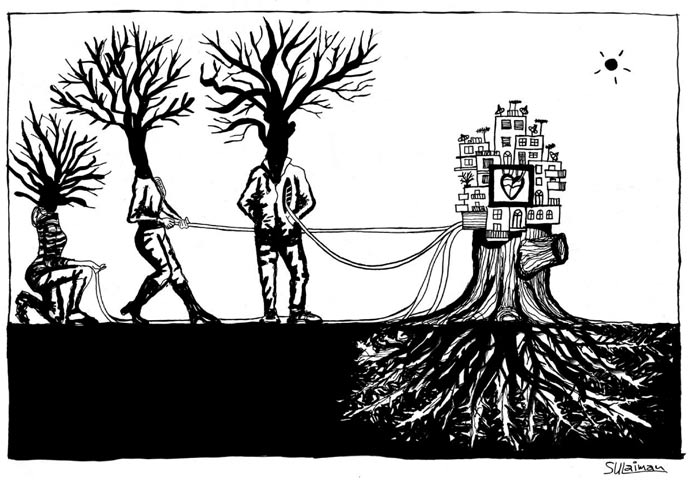

We know that people form their view of the world using things that they experience in the museum – and for this reason we should not present linear, self-contained views of cultures, which correspond neither to the reality of our lives, nor to the reality of the objects themselves. Instead, our understanding of the objects is that each exists within a transcultural network; when we relate the narrative of an object, we automatically talk about it either in connection with the cultures that preceded Late Antiquity, or in connection with the contemporary cultures in China, Europe, and the Mediterranean, or in relation to ourselves today. We very rarely discuss an object in terms of its developmental or cultural history alone, as if it had just fallen from the sky.

Since 11th September 2001, it has barely been permissible, in our society, for young Muslims to evolve their identity without having to explain themselves.

It is very difficult, because we are supposed to give answers to a key question of our society's development – answers that have no relation at all to our concerns and yet have a direct political impact. People talk about closed cultural spaces, about THE Islam, and they propagate a strongly religious view of culture.

So we asked ourselves how we could counteract that. In the context of a museum, that means asking: How can a visitor access knowledge here? What means of access do we have? What trans-regional references do we offer? What happens to visitors in the exhibition? And if Islam is such a key issue, why are no schools coming to us?

When we started working in schools, we noticed that nowadays many more Muslims than before are asking themselves the question "Who am I?" Since 11th September 2001, it has barely been permissible, in our society, for young Muslims to evolve their identity without having to explain themselves. This development has exacerbated social polarization, as a result of how people define themselves and of how they are defined by others.

The museum offers a contrast to that. We show how different societies have grown together and how they have grown apart as they developed in different directions, how Christians, Jews, and Muslims belong together, and how they have created culture independently of their own belief systems. This does not fit well with the present-day mentality of cultural categories and its culturalist approach – and that is exactly why we have something worth saying to our society now, and why we offer programs for Muslims, beginning with education in mosques.

You have also created the Multaqa project, which offers a solution to the task of integrating refugees in Europe, using cultural means. How did that come about and why is it so successful?

Multaqa offers Syrians, Iraqis and Arabic-speaking refugees a low-threshold opportunity to discover cultural institutions. There they learn something about themselves and realize that they are respected. And they discover German history. Through this new form of guided tour, we have succeeded – to start with purely by chance – in bringing objects from the past into the present and offering them as catalysts for reflection.

We knew that this format would not permit us to convey the usual package of specialist knowledge acquired over a period of years. So together with the educational department of the National Museums we began to develop a dialogical tour, in which the guides choose objects that are important to them and discuss them with other refugees. It was a smash hit. I had always thought that mediation work was about "conveying our knowledge better," but now I realize that it also means saying "I am a curator, but I don't have to decide everything," and surrendering part of our interpretational authority as scholars over what is conveyed. The point is to allow people to use the space for themselves, with their own approaches, with their own questions. Having to open up has shown us that we have yet more very different opportunities for developing our relevance to people, if they are asked to join in the discussion and contribute their own realities to it.

"Multaqa: Museum as Meeting Point"

As part of the project “Multaqa: Museum as Meeting Point – Refugees as Guides in Berlin Museums”, Syrian and Iraqi refugees are being trained as museum guides. They provide guided museum tours for Arabic-speaking refugees in their native language at the Pergamonmuseum, the Bode-Museum and the Deutsche Historische Museum in Berlin. Initiated by the Museum für Islamische Kunst of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, the project has been sponsored by the German Federal Ministry for Family, Seniors, Women and Youth and is now supported by the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media. more

How important are the objects in this?

The objects are not misused or violated, they rather speak of what is contained in them and no more. Every object is marked by migration – take our clothes, tools, and everyday items for example: all created globally. Consider the old technologies of urban civilization, the alphabet, the transregional links and networks in trade and manufacturing: these are all ideas. Ideas have migrated, knowledge has migrated, and once you look more closely, you find a great many stories to be told about why we are as we are: as a result of exchange with others. Objects are wonderful for illustrating that, because they are the materialization of ideas, technologies, and knowledge. Bad and good ideas spread at a mind-boggling speed, which is something that you come to understand quite well when you look at the objects. When you talk about them, you end up talking about yourself and the human race, and can give the objects a meaning even today. You can reflect upon objects. What does a painting from the Thirty Years' War in the German Historical Museum actually tell us? And how can we understand it today?

This recalls the Humboldt Forum's approach as a universal museum of the 21st century: to use objects as a means of presenting the entire world and its developments. There is the problem, however, that many of the objects entered the collections in a colonial context. Do you have similar difficulties?

In 1904, Wilhelm von Bode (the "Bismarck of Berlin's museums") and Friedrich Sarre, a pioneer of Islamic art history, founded and built up the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum's Islamic Department, which would later become the Museum für Islamische Kunst (Museum of Islamic Art). What would they have said if they had known that in the 21st century, against a backdrop of controversy over Islam, civil war in Syria, and a refugee crisis, the museum would be more than just a place for safeguarding the Aleppo room and elaborate prayer niches, or studying the Mshatta facade? The museum’s staff are active on many fronts: securing data in Syria so that the increasing destruction of Aleppo can be remedied at some time in the future; offering education about Islam in schools and mosques, and not least in their own museum with exhibitions about cultural transfer.

The Museum für Islamische Kunst is in demand: In late September 2016, the German Foreign Ministry is coming here to hold a symposium, attended by Foreign Minister Steinmeier and other high-ranking figures, on the question of how intercultural dialogue can be encouraged by means of artistic and cultural projects. At the beginning of August came the news that the Gerda Henkel Foundation will grant €750,000 to a follow-on project for the Syrian Heritage Archive project. It is all but raining awards and recognition. In early September, an emissary of the Vatican paid a visit to learn about the concept behind the Multaqa project based here, which provides badly needed answers on topics of integration and participation. So it is possible to do something.

What plans does the Museum für Islamische Kunst have for the next few years? Where is there still work to be done?

At the moment we are making alterations, which gives us a welcome opportunity to reflect and to refine things. The participatory approach is one that makes a lot of sense for us. It necessitates – painful though it may be – considering even more closely whether what we have devised for the mediation and the new displays is comprehensible to visitors. For example, when I state my basic tenet that "Islam was born in Late Antiquity," no one apart from a few scholars knows what I mean. It refers to dual link: Islam comes from somewhere – it didn't just fall from the sky – and it is associated with us, because we too have our origin in Late Antiquity. The claim that Islam has no place in Germany is irrelevant to us, because the museum itself is a statement that Islam, as far as cultural history is concerned, has always been part of our reality. Of course, we have only had Muslim life in Germany since the 1960s, but the cultural connections are nevertheless considerably older. These matters are very difficult to convey, because they require a lot of complex knowledge about a subject that people think they already know all about.

The claim that Islam has no place in Germany is irrelevant to us, because the museum itself is a statement that Islam, as far as cultural history is concerned, has always been part of our reality.

They already have a firm idea of Islam, but a whole lot of fears have got stuck to it, like a piece of chewing gum that is hard to peel off. So we need to refute a great deal of misconceptions before we can move on to a higher level of reflection. We want people to take more with them from their museum visit, to go home with ideas, and learn something for themselves. Unfortunately, there is still no museum of Islamic art that does it in this way, so we have nowhere to copy from, and have to develop this museum by ourselves. That's a lot of fun, of course, but it is also difficult. In this we have the support of the Board of the SPK. I would also like to do yet more school projects, because we need to generate a broader appeal.

And if I had even more resources, I would like to do projects on the periphery of German society. If you look, for example, at the results and the election campaigns for the regional assembly election in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, or even here in Berlin, you can detect so many fears and so many prejudices. If we don't talk to people and say what we have to say, even if it hurts, then sooner or later the social consensus in Germany will come crashing down around our ears. That is more of an imperative from the perspective of societal development. It would be wonderful, by the way, if we did not need to do that, but could simply carry on our research in peace.