In discussions about the Humboldt Forum, people often raise the question of how the museums whose collections are to be exhibited in Berlin Palace are dealing with the colonial-era objects in their collections. Viola König, director of the Ethnologisches Museum of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, explains how project research into ethnological objects works.

During the summer holiday season, the newspaper supplements continually returned to the subject of provenance research into the ethnological collections that are scheduled to move into the Humboldt Forum. It was claimed that they were stained with blood from the colonial period.

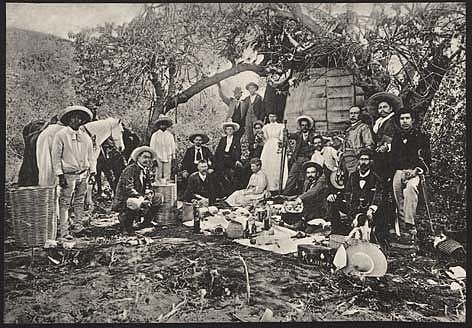

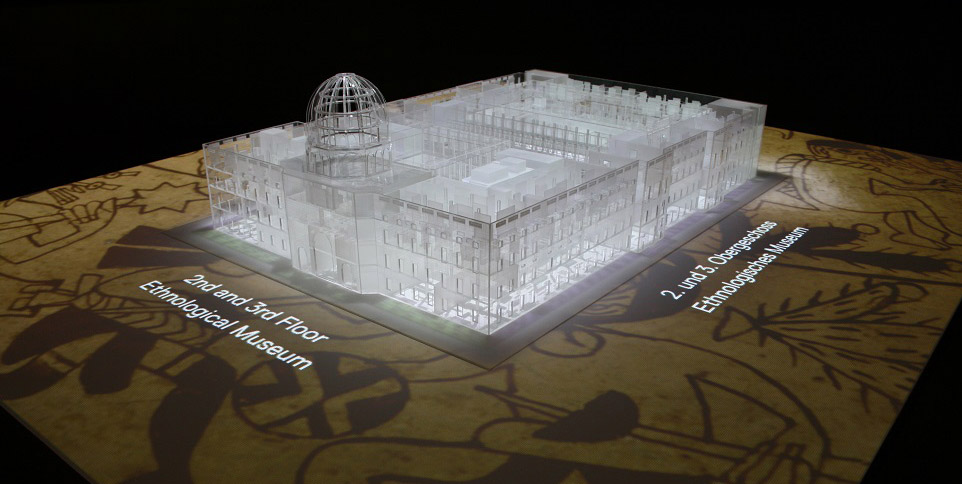

A delegation of elders of the Huichol, an indigenous people from Mexico, puts the collection of ritual objects from their ancestors in the Ethnologisches Museum back into the correct arrangement. The museum had lost this knowledge over the course of time. © Viola König

In principle, so the argument went, these collections are just accumulations of misappropriated goods, so they should be investigated in this respect and ultimately returned. Demands for more provenance research are now being repeated more stridently by political representatives and institutions, which for decades have been pressuring museums to focus increasingly on holding exhibitions and which ultimately made their financing dependent on this supposed indicator of performance. This emphasis led to the impression that museums neither undertake research into origins nor regard it as important. The Humboldt Forum has already proven successful for the simple reason that this area of research – regarded for many years as of secondary importance – is now attracting the public attention and funding that it deserves. People in this country assume that collections from very different corners of the world can be treated in the same way. It is precisely this approach that is beginning to encounter resistance from the people of those places. What they are demanding instead is self-determined research beyond victim-perpetrator premises.

Provenance research, however, is only one aspect of the complex investigation of ethnological collections, in which the focus lies on object biographies, including every change of location or ownership. Provenance centers on the perspective of today’s owners, whereas an object biography considers the object itself. Provenance research that confines itself to reconstructing the circumstances under which a collection came to Europe is incomplete and biased, even Eurocentric.

In what ways did objects become part of the collection?

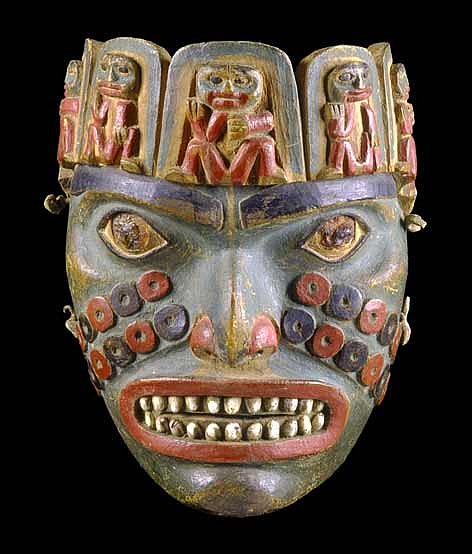

Another inseparable part of the overall research, besides reconstructing the biography and the provenance trail of a given object, is to decode its functions and statements. An object whose origin is known, but whose function, context, transformations are not, is an object that has been inadequately researched – and can thus only be seen from a Western perspective.

Only all of the factors together produce a coherent picture. They are the prerequisite for deciding whether that object should be kept in a museum or, if possible, returned to a community. Some museums in the United States now preserve returned objects on behalf of those communities.

Provenance research that confines itself to reconstructing the circumstances under which a collection came to Europe is incomplete and biased, even Eurocentric.

Middlemen and traders, including indigenous people, play an important role in researching the provenance trails of ethnological objects. Their personal backgrounds are informative when it comes to the question of what objects were collected and why. Middlemen are often only known locally. This means that direct cooperation with the societies of origin is indispensable. An object’s history can only be pieced together through close contact, because people on the spot have information that is not known in the museum and vice versa. Collectors from Europe were always dependent on local networks..

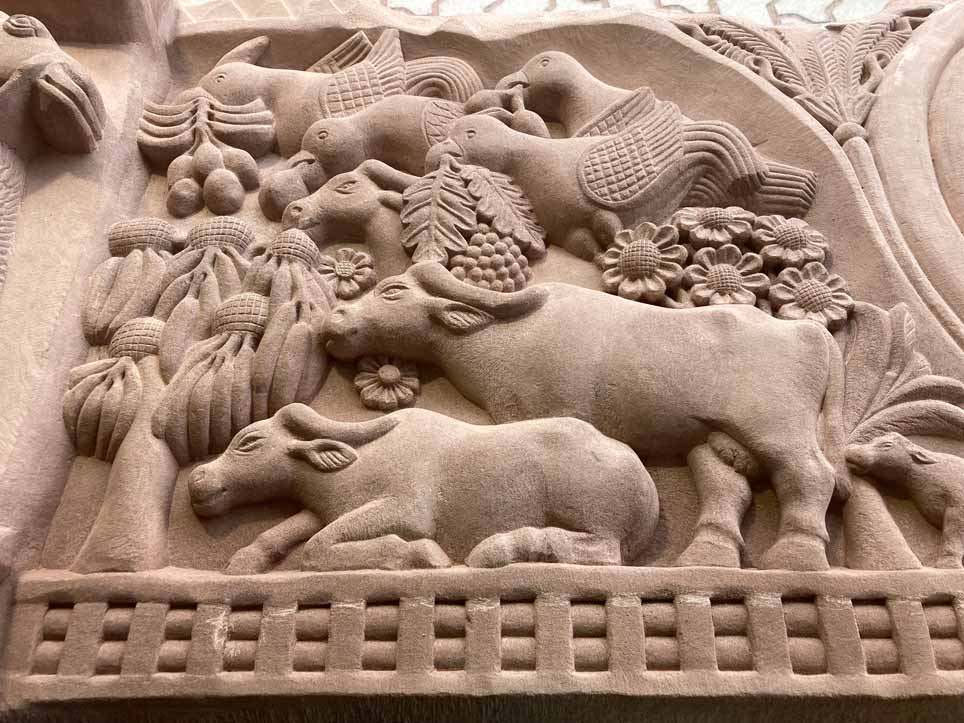

The largest collection, numerically, in the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) does not come from the former German colonies in Africa, Oceania, or Asia, but from North and South America. Germany had no colonies on either of the latter two continents, but did experience mass emigration to them from the nineteenth century onward.

Trading companies operated between their American locations and their home base. Some owners, such as Gretzer and Gildemeister in Peru, returned to Germany with huge collections after working in the business successfully for decades.

The provenance trail is a long one

Collectors such as Johan Adrian Jacobsen and Eduard Seler, whom the museums of Europe began sending out in the nineteenth century, primarily relied on local contacts to help them plan the itinerary of their journeys. As well as providing tips and warnings, these individuals would offer objects from their personal collections.

Even when their names are known, like those of Paul Schulze and Wilhelm Bauer, the provenance trail of the objects is still a long one. In most cases, it peters out among nameless suppliers at a local trading post and is lost again in later times on the art market. So where the objects really came from remains unclear. How do we deal with such cases at the Ethnologisches Museum? To start with, we use decoding techniques such as stylistic comparison, material analysis and, above all, knowledge about the material culture of the object’s makers.

It is interesting that the exchange of goods between indigenous and European traders with a mutual interest in “exotica” also brought hybrid creations onto the global market: deerskin waistcoats with British navy buttons and Chinese coins, or pigskin boxes with floral decorations – an adaptation of Chinese tea chests. These examples from the northwest coast of the American continent are just two among many that can be found in the ethnological museums of the world.

Export bans often had no effect

At times, the provenience (the actual location of a find) would be deliberately concealed by the collectors, especially in the case of archaeological objects. They did so not because excavating without a permit was necessarily illegal at that time, but in order to avoid revealing sources or sites that they expected to yield further discoveries.

Laws to prohibit the export of archaeological objects were passed in many Latin American countries at the beginning of the twentieth century, but they were largely ineffective. European scholars continued to work hand in hand with local collectors, many of whom felt – as proud citizens of newly independent nations – that if an artifact was going to a European museum, then this was an acknowledgement of its worth.

What motivates your researchers in the countries of origin?

In the current, 21st-century review of the collection, middlemen appear on the scene once again. They themselves do not belong to an indigenous group, but they supposedly represent them. Such claims must be checked very carefully by the museums. Who do they represent? What is their motivation? Are they authorized and, if so, by whom? What authentic information do they have and how do they deal with it? Have they been living in the local area for a long time? Why do they enjoy the trust of the communities? Are they seeking contact with Europe in good faith, or do they have interests of their own, perhaps even a political agenda?

The museum world is familiar with the principle of the division of finds in the contexts of natural history museums and archaeological excavations. But groups of ethnological objects might also be split up if the traveling collector had been commissioned by several clients from different institutions, or if he had acquired both natural and ethnological objects. In all such cases, there was a risk that no copies would be made of the documentation, which remained with one part of the collection, depriving the other objects of their context.

Museum ethnologists therefore treat the principle of the “intact collection” as sacrosanct. It was sometimes possible to make plaster casts to take the place of original items that were relinquished. It is particularly problematic when original items were relinquished in the belief that they were duplicates, since the pertinent correspondence in such cases was not fully recorded. Copies were simply not made of handwritten letters when they were sent. This means that today, they have to be sought in the archives of the recipients. Research into the acquisitions of single objects on the art market is especially difficult, if not impossible.

Furthermore, collections in ethnological museums reflect a masculine world. The collectors and explorers were almost all men. On expeditions, contact with women was forbidden “in the field,” and it could indeed put your life in danger. Ethnological museums are veritable weapons arsenals: they house hundreds of spears, lances, and harpoons, but these are not mass-produced goods by any means, because each specimen is different. When the collectors did turn their attention to “women’s” utensils, they occasionally let themselves be fobbed off with unserviceable crockery. Some of the Tibetan cauldrons and jugs acquired by the celebrated Schlagintweit brothers have casting defects and are unfit for their purpose. They were probably disposed of to the Schlagintweits for a good sum of money. So, sometimes, collection research may be “fake research,” to borrow a phrase.

h „Fake-Forschung“.

Eventually, post-colonial discourse and post-modern deconstruction initiated a critical process that challenged the Western prerogative of interpretation and focused attention on the illegality of acquisitions.

On every continent, the history of European expansion is marked by exploitation, misery, hardship, and unlawful appropriation under conditions of inequality. The collections that date from between the eighteenth and the twentieth centuries are a material reflection of this history. The expedition members took it as for granted that they, as Europeans, had a better right to interpret and evaluate the world than others did. Any means of gaining scientific knowledge seemed justified to them, even if it sometimes conflicted with ethical standards. The collections, including human remains, were intended to illustrate this knowledge. Later on, in the twentieth century, modern artists in the West borrowed aesthetic concepts from the “exotic” peoples of Africa, Oceania, Asia and native America and declared them to be art, but kept silent about their origin.

Eventually, post-colonial discourse and post-modern deconstruction initiated a critical process that challenged the Western prerogative of interpretation and focused attention on the illegality of acquisitions. At times, the inclusion of research into indigenous involvement in the collections has led to unexpected insights. As museums sprang up in Europe and North America and vied to assemble the best and largest collections, profiteers and freeloaders were to be found in both the local and the Western camps, although their standings were not equal. At such times, European collectors had to rely on local middlemen and agents in order to make any deals at all. There are documented accounts of indigenous “traitors” who led the way to graves that they then helped to open, and who obtained ritual objects and other culturally important goods by night. These were perilous undertakings, because if the crime came to light, the community gave short shrift to the transgressor, as a deterrent to others.

The disclosure of such illegal deals and their consequences is also important to the heirs of the societies of origin today, because it makes the simplistic concept of victims and perpetrators more differentiated with regard to aspects such as “complicity” with European collectors.

“Fieldwork turned on its head”

One particularly effective method of collection research was described by a Yupik delegation from Alaska at the end of the nineties as “fieldwork turned on its head.” Ethnological museums in Europe are being visited ever more frequently by the heirs to the societies of origin. For example, members of the Dena’ina and Chugach corporations from Alaska, the Huichol of Mexico, and the Yakuts from Siberia organize and invest in these expensive study tours themselves. Examining and discussing the collections together is exciting and illuminating in equal measure and it brings new insights for both parties. Historical collections of photographs are of immense importance in this context. They offer a chance to identify individuals, sometimes even the artists who created the works, and whose names are still known among the community.

The future also lies in digitization

Provenance research, however, should not be a question of quantity versus quality, weighing up as many objects as possible with a known secondary provenance against a few very well researched objects. The focus must rather be on the digitization and publication online of all the basic data: inventory number, object description, collector, place and date of acquisition, and above all photos, drawings, and historic sound or film recordings..

The more people who gain access to these data, the greater is the likelihood of being able to study objects in relation to their provenance, the context of their origin, and their function in the societies of origin. A lot of money will have to be spent on translations of accompanying German-language source material, and for transcriptions from Sütterlin script or extinct shorthand systems such as Stolze-Schrey, which are just as foreign to the descendants of the societies of origin as to the German scholars of today.

Only when all of the interested parties have access to this data will it be possible to build and operate a global digital platform for sharing knowledge. The goal is networked research into collections, an objective approach that is independent of the currently prevailing requirements dictated by political and academic theory and which avoids any bias caused by focusing on one particular period of an object’s biography. Ethnological museums are very active in both respects, digitizing and researching their huge collections and thereby constantly expanding their own international networks.

This commentary by Viola König was first published in „Die Welt“