By the end of 2022, a reconstruction of an ancient Indian gate will stand outside the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The city’s new landmark is being made by the Bavarian stone-working company Bamberger Natursteinwerk Hermann Graser, with the assistance of two expert stonemasons who have come from India specifically for the project. Elena Then visited the company in Franconia to find out more.

“This is really quite special,” says Nina Graser on this overcast, somewhat chilly day in early autumn as we stand outside Bamberger Natursteinwerk Hermann Graser, a stoneworking company in the Franconian town of Bamberg. The eastern gate of Sanchi’s famous stupa is being meticulously reconstructed here. It will be completed by November 2022 and erected in Berlin, in front of the Humboldt Forum, by the end of the year.

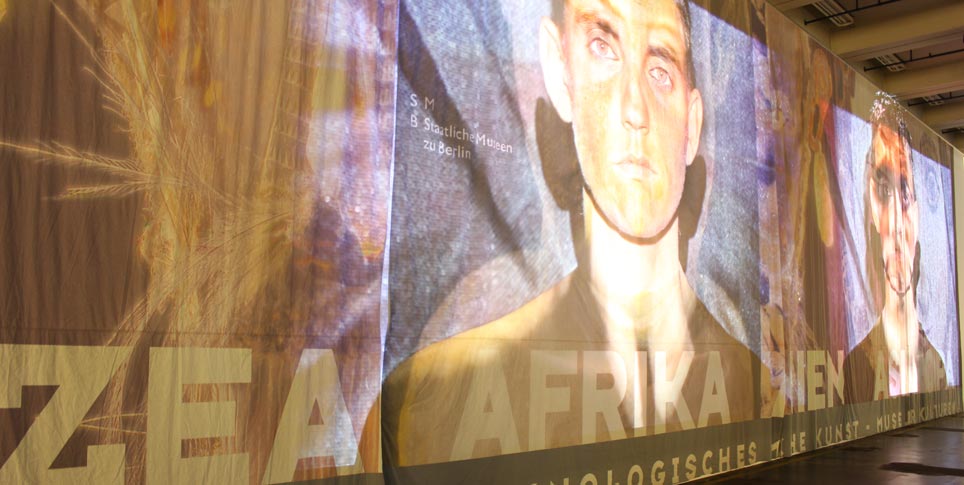

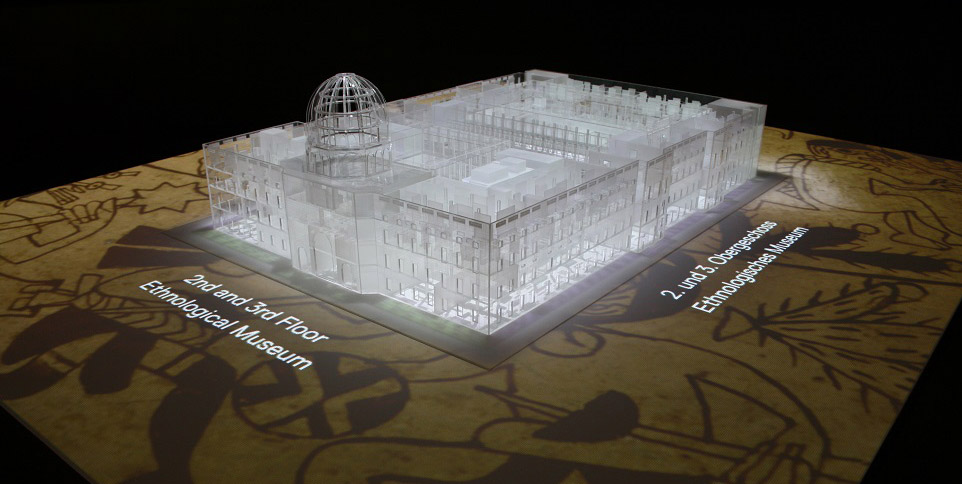

It was about five years ago that the Humboldt Forum’s founding directors, Neil Mac Gregor, Hermann Parzinger and Horst Bredekamp, hit upon the idea of installing a second Sanchi gate in Berlin, this one right in the city center. A cast of the gate had previously been erected in the grounds of the earlier Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum) in Dahlem, where it still stands today. The Sanchi Gate outside the Humboldt Forum will not only serve as a lithic reference to the non-European collections on display inside, but also enter into a dialog with the Humboldt Forum’s Baroque facade, itself a reconstruction of the Berlin Palace. It will communicate with the city space beyond this, too, acting as a counterpoint to the Brandenburg Gate at the other end of the city’s majestic boulevard Unter den Linden. The Sanchi Gate project was made possible by the Stiftung Humboldt Forum im Berliner Schloss (Berlin Palace – Humboldt Forum Foundation), which will display it on its grounds near Portal 5.

The Herculean task of creating the replica will be accomplished by Bamberger Natursteinwerk Hermann Graser. Although the company is based about 400 kilometers away, it is well known in Berlin, having carried out much of the work on the Berlin Palace façades, including the north and south façades and the entrance through Portal II. It was also part of the team that reconstructed Portal I, Portal V and the balustrades, and it created the curved stone benches in front of the building.

Whether dark granite, structured sandstone or light quartzite, the company’s twenty-plus quarries ensure that, whatever the project, it can source appropriate materials. “The important thing for the Sanchi Gate is that the stone should be homogenous in color and very fine-grained,” explains Nina Graser. “That’s why we’re using what’s called ‘red Main sandstone’ from Röttbach in Lower Franconia – it closely resembles the original sandstone in India.”

Historical Background

Berlin’s Sanchi Gate is a copy of one of four entrance gates to the Great Stupa at Sanchi, one of ancient India’s most important Buddhist monuments. A massive domed structure designed to hold and honor the relics of the Buddha and Buddhist saints, it and neighboring monuments have been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Its core dates back to the time of the emperor Ashoka the Great, one of the first great patrons of Buddhism, in the 3rd century BC. Worshippers honored the holy relics inside the stupa by walking around it clockwise. This open-air circumambulatory path was thus a sacred devotional space, and it was clearly demarcated as such and protected from the profane outside world by a massive stone balustrade. The stupa complex at Sanchi was expanded in the 1st century AD, the main change being the addition of four elaborately carved, ornamental gateways at the eastern, southern, western and northern points of the balustrade. Berlin’s Sanchi Gate is modeled on the eastern gate, which was the main entrance. Mounted in front of the new replica gate, there will be a miniature bronze model of the entire complex. This is designed to be touched and it will have an explanatory text in Braille so that visitors with visual impairments will be able to appreciate the new monument.

When British colonial officers started studying Indian antiquities in the nineteenth century, they found the Great Stupa at Sanchi and its neighboring structures fully intact despite their great age – a very rare occurrence. They were awed by the archaic imagery of the gates, and soon almost every discussion of ancient Indian art began by referencing the Sanchi gates.

From 1869 to 1870, British lieutenant Henry Hardy Cole worked to create a cast of the eastern gate, once the main entranceway to the Great Stupa, for London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum). The replica was composed of many separate pieces and required a great deal of time and effort to make. Once it arrived in London, the South Kensington Museum made several copies and offered them for sale to other European museums. One of these copies, a faithful plaster-cast reproduction of the original, was purchased by Berlin’s Museum für Völkerkunde (Royal Museum of Ethnology ) in 1886. The one hundred or more components of the plaster reproduction are now in Friedrichshagen, in a storage facility belonging to the Dahlem branch of the Museum für Asiatische Kunst (Museum of Asian Art).

By Martina Stoye

Bamberger Natursteinwerk Hermann Graser scanned the plaster casts with 3D imaging equipment at the storage facility and then used special computer software to create 3D models. Once a digital twin had been created of the Sanchi gate copy acquired in 1886, the data could be used to program the company’s enormous stone-milling robots. Bamberger Natursteinwerk has been a major player in the design and practical development of these machines since 2007 and uses them to mill basic shapes before the stonemasons start their work – although to describe this stage as “basic” is not doing the machines justice. The machine-milled stone actually looks quite good, and the only things that still need work are details such as faces, leaves or ornamental elements. This is where the stonemasons come in: they finish the job, carving the stone based on photographs of both the plaster casts and the current gate in Sanchi, India. Up to ten stonemasons may be working on the pieces for Berlin at the same time.

Hermann Graser, the company’s director, explains that their job is not to try to add back any detail that weathering or other damage may have erased, but to create what he calls an “archaeological copy,” i.e., one that is true to the original. That gets complicated when the 3D scan of the plaster cast made in 1869/70 looks different from the gate in India, which has continued to change due to external factors such as weather and restoration. At this point, experts have to be brought in from a commission consisting of the architectural team of Killinger & Westermann, the engineering office of Thomas Bolze and the curator for south and southeast Asian art at the Museum für Asiatische Kunst, Martina Stoye. They consult with the stonemasons at Bamberger Natursteinwerk and together decide how to proceed.

“Every project has challenges, difficulties that have to be overcome. Our decades of experience have taught us well. We learn something new on every job, and we can apply that knowledge to subsequent projects and build on it. So every piece that we work on benefits from the experience we gain from the jobs before it,” says Nina Graser. This latest copy of the eastern Sanchi gate will also benefit from the assistance of carvers from India. “Very early on in the project to erect a replica Sanchi Gate in front of the Berlin Palace, there were talks with the Indian embassy. The idea was to use outdoor space to draw attention to the exhibitions inside the Humboldt Forum and to mark this institution as a place for collections from around the world. Considering the cultural significance of the Sanchi Gate and the sophistication of India’s stone-carving tradition, we believed, along with the client, that it would be a good idea to bring in Indian stone carvers for tips and advice on carving this Indian artwork. We got in touch with them through the European & International Federation of Natural Stone Industries, whose current president is Hermann Graser. It’s been great to see how stone carvers can share knowledge and skills across cultures and learn from each other,” says Graser enthusiastically.

We set off for the quarry with a large bottle of salty lassi as refreshment for the two Indians. The trip does not take long: after a few minutes on the highway, we drive past a village and up a narrow country road into the woods. A sign at the entrance announces “Danger: Blasting Area!” The first thing you see is a cozy-looking house with wooden windows. This structure, which looks like a holiday home in Bavaria, houses some of the company’s staff, considerably shortening their commute. From a factory just across the way can be heard the hammering of chisels against stone. Inside are groups of carvers standing at their workbenches. The two Indian consultants have been in Bamberg since September. They have worked on similar projects in India and have lived abroad before as well.

The degree of detailed carving involved in creating the new replica of the ancient Indian Sanchi gate makes the job a special one for the company’s staff. “It really is different, so delicate, with the leaves of plants we’ve never seen before,” says Joachim Mühlen, one of the ten stonemasons working on the Sanchi Gate. He is all the more pleased to be working with the Indian carvers. They use different methods, working by hand for the most part. It took them a while to feel comfortable with the fine pneumatic hammer that the German carvers use. You don’t notice any difference, says Mühlen with a smile. “The result is the same, it just goes a little bit faster.” When it comes to fine details like faces, however, the Germans too prefer to rely on their hands. It is impressive to see the precision with which the carvers work, all the while consulting A3 photos of the plaster casts and the original, approximately 15-meter-high gate in India.

As meticulous as the work must be, there is not much time to do it in, explains Nina Graser: “Once we got the contract to create the archaeological copy of the Sanchi Gate in January 2022, we produced the 3D scans in early March and completed the planning of workshop and assembly operations by May. While this was being done, the raw material was being sourced in our quarry, and after that, we started processing the stone. Preparatory work at the construction site will begin in mid-October. Roughly thirty pieces of worked stone will be transported to Berlin by truck and assembled on site. Starting in mid-November, the Sanchi Gate will be erected near Portal 5, on the side of the Berlin Palace that faces the Lustgarten.”

Before the year is out, people will be able to view and walk around the gate – a masterpiece of stone carving and a project that, entirely in keeping with the spirit of the Humboldt Forum, transcends national borders.