Researchers from the Ethnologisches Museum are working closely with their Guatemalan partners to study these huge monuments.

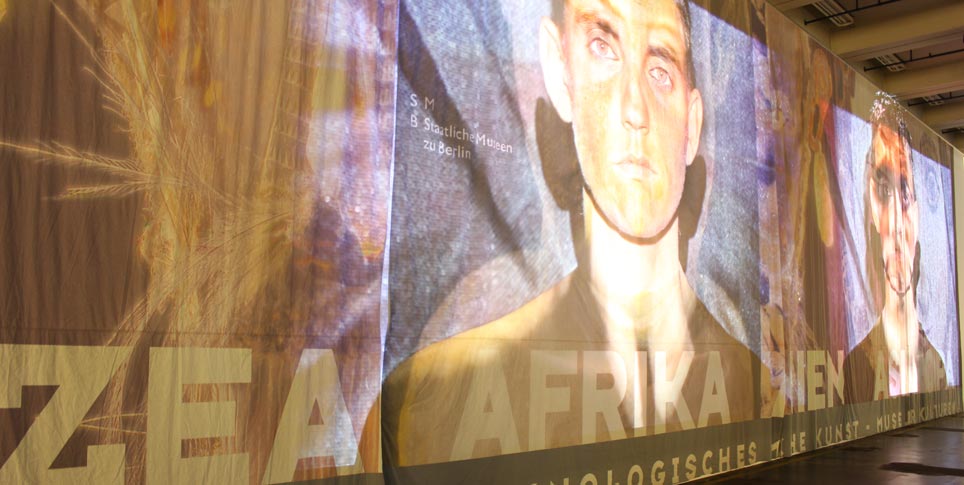

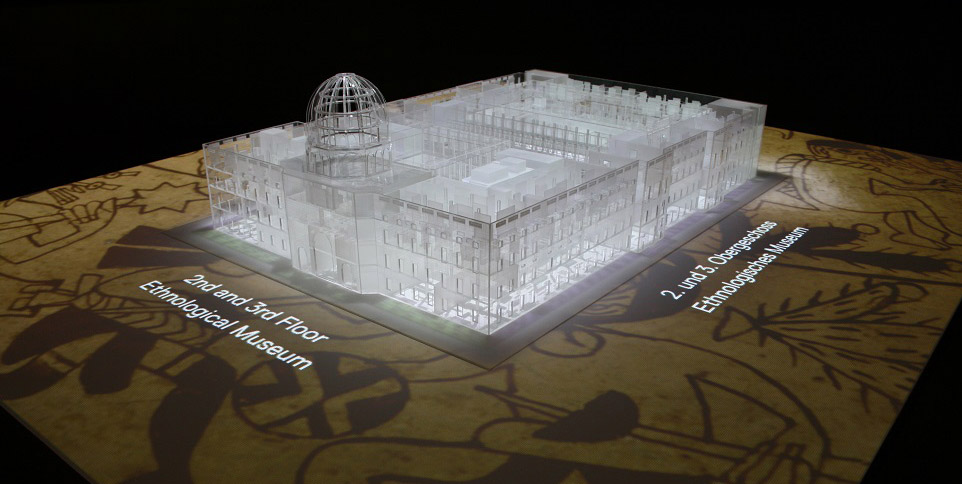

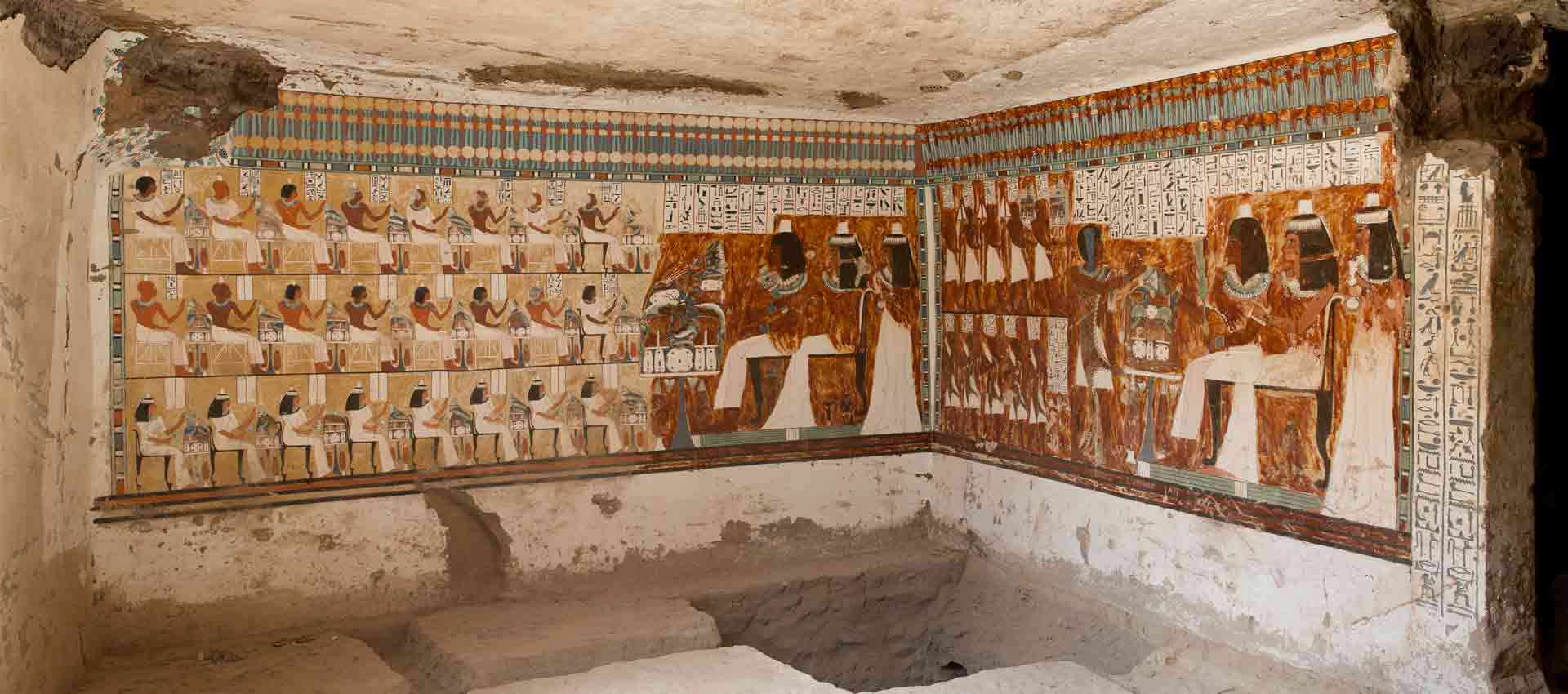

Room 207 is one of the Humboldt Forum’s most impressive spaces. Its high ceilings and the light streaming in through the windows give it a bright and friendly atmosphere. On the southern wall is a mural consisting of terracotta tiles created by Mariana Castillo Deball, a well-known Mexican artist. And in the middle of the room are the steles of Cotzumalguapa with their fascinating reliefs. There are eight of them in all, as well as several other monuments. It is a place to linger – and, of course, to enjoy. “The presentation of the monuments of Cotzumalguapa is definitely a highlight of the Ethnological Museum,” says Ute Schüren, curator of the collections on Mesoamerica, the cultural area that extends from Mexico to Costa Rica.

Alejandro Garay from the University of Bonn explains the visual language of the Cotzumalhuapa culture during a joint event of the Embassy of Guatemala and the Ethnologisches Museum on the history, acquisition and cultural significance of the Cotzumalhuapa steles on April 27, 2023.

Photo: © SPK / photothek / Kira Hofmann

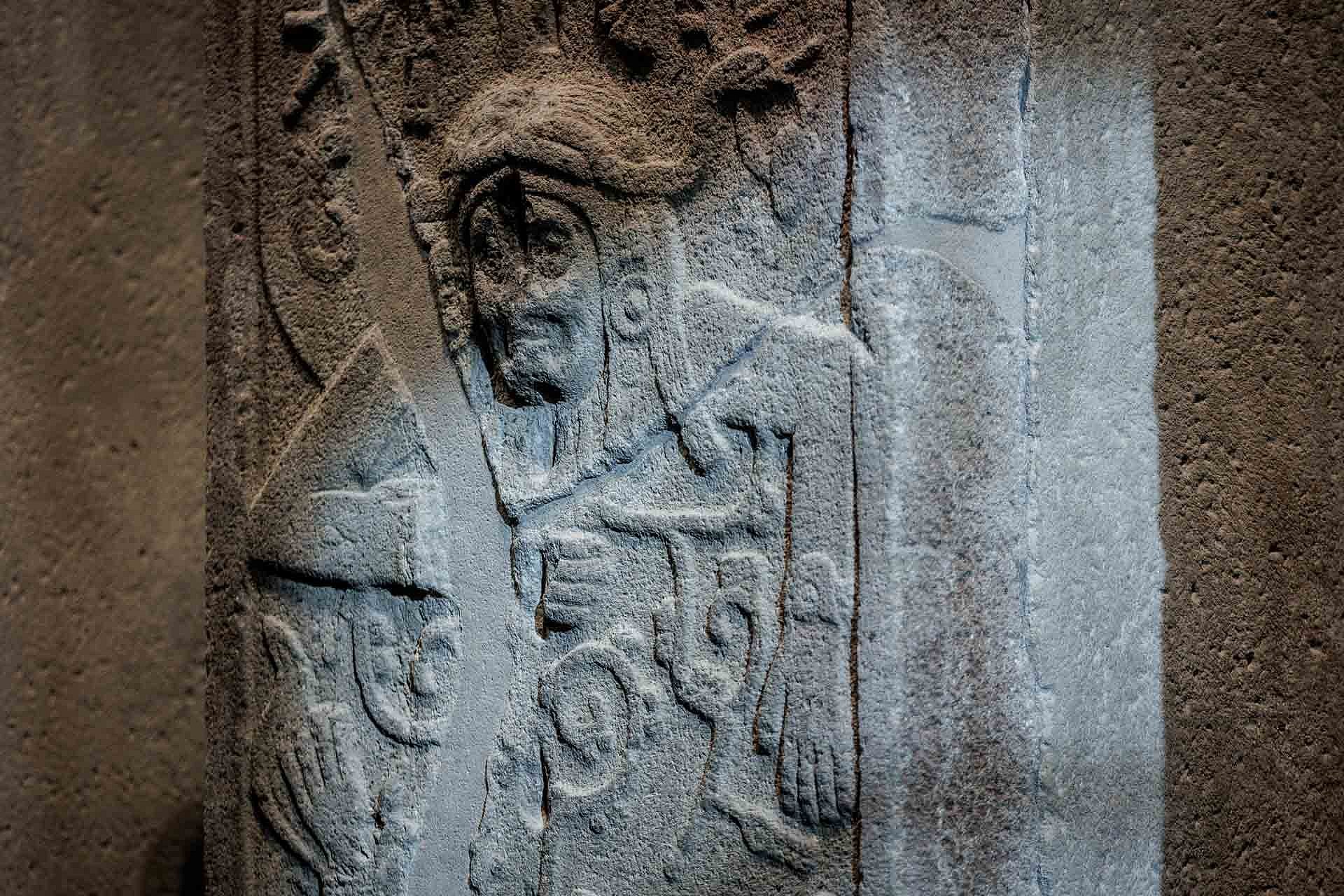

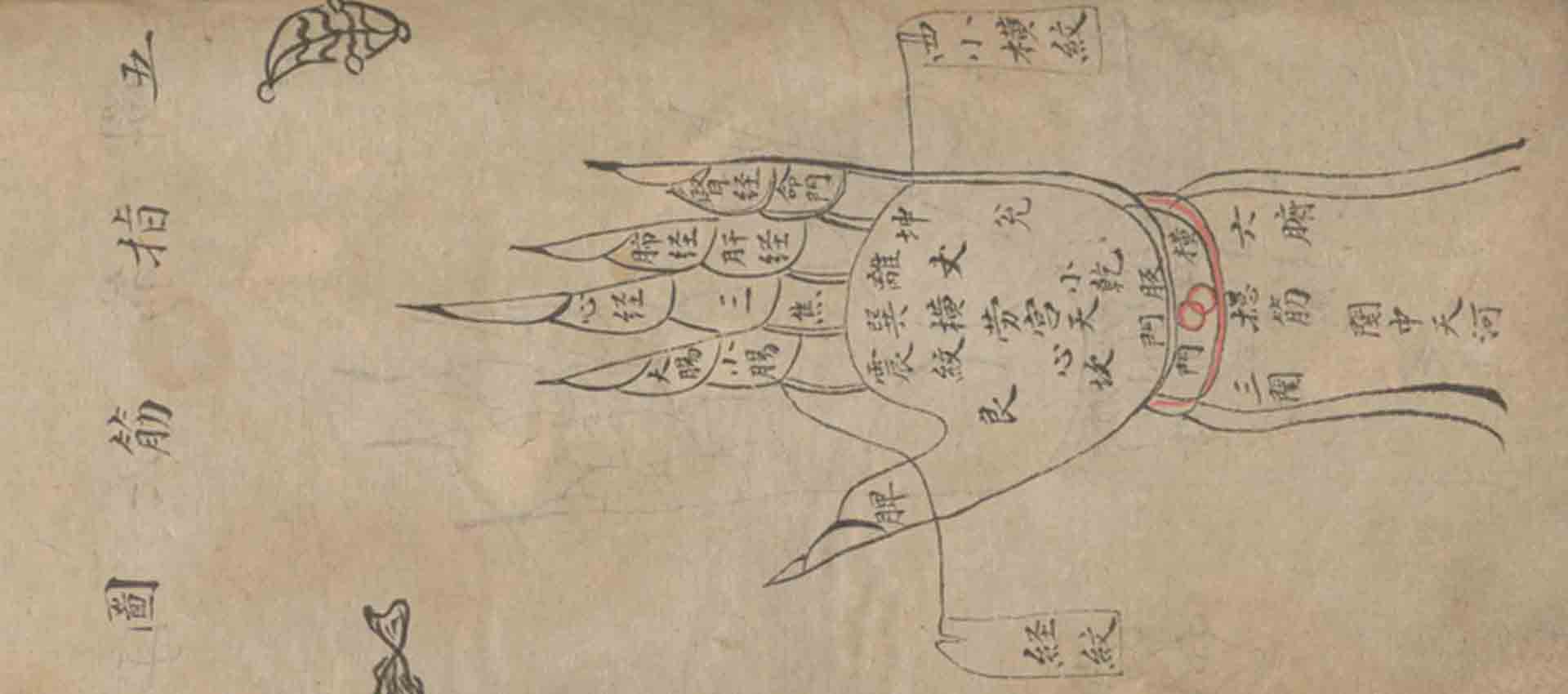

Of course, it is not just the wonderful atmosphere of the room that captivates visitors. The reliefs themselves instill a sense of awe, as do the stories they tell: stories of the highly independent Cotzumalhuapa culture on the Pacific coast of Guatemala, which flourished between 650 and 950 AD, and which is very different from the neighboring Mayan culture. To this day, it poses many questions for researchers: What exactly was the nature of this regional culture? What language did the people speak? What exactly do their writings signify? Only about thirty characters are known, but so far they have not been deciphered. What is clear, however, is that the reliefs on the steles show people communicating with their ancestors and with deities. They are making sacrifices to them, including human sacrifices, and asking them for fertility and a good harvest. Other monuments show figures such as rulers, along with their insignia, and the skeletal god of death.

What is striking about the eight steles is the many references they make to a ball game, different versions of which were played at various times throughout Mesoamerica. It was not so much a sport as a ritual. Frequently, ball fields were more than just recreational areas; they were also places to make sacrifices. It is no wonder, then, that the Spaniards, who wanted to spread Christianity, banned the game soon after their arrival. In one variation of the game, players had to hit a rubber ball weighing several kilograms with their hips. This was not without risk: players wore wide belts to protect themselves from the impact, as can be seen clearly on the steles.

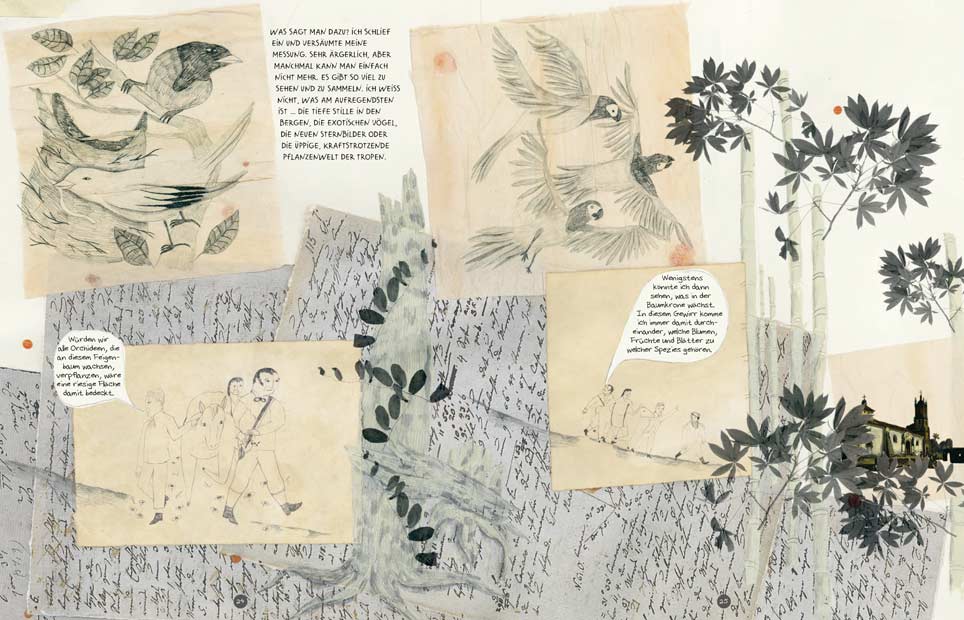

What is particularly important to Ute Schüren is not just adding to what is known about the collections but also making this knowledge accessible to a broad audience. This public outreach takes place via the Research Campus Dahlem and through exhibitions, workshops, and events and occurs in close cooperation with local partners and international and national scientists. One recent example was the 24th Mesoamerican Studies Conference, which was organized by the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum), the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut (Ibero-American Institute) and the Institute for Latin American Studies at the Freie Universität Berlin. The conference brought together more than eighty researchers who shared their latest findings and listened to twenty-eight exciting presentations.

Likewise, when preparing the current exhibition of the Ethnologisches Museum at the Humboldt Forum, the former curator, Maria Gaia, worked closely with the Guatemalan archeologist Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos to research the enormous Cotzumalhuapa monuments. He teaches at Yale and is a leading authority on Cotzumalhuapa culture.

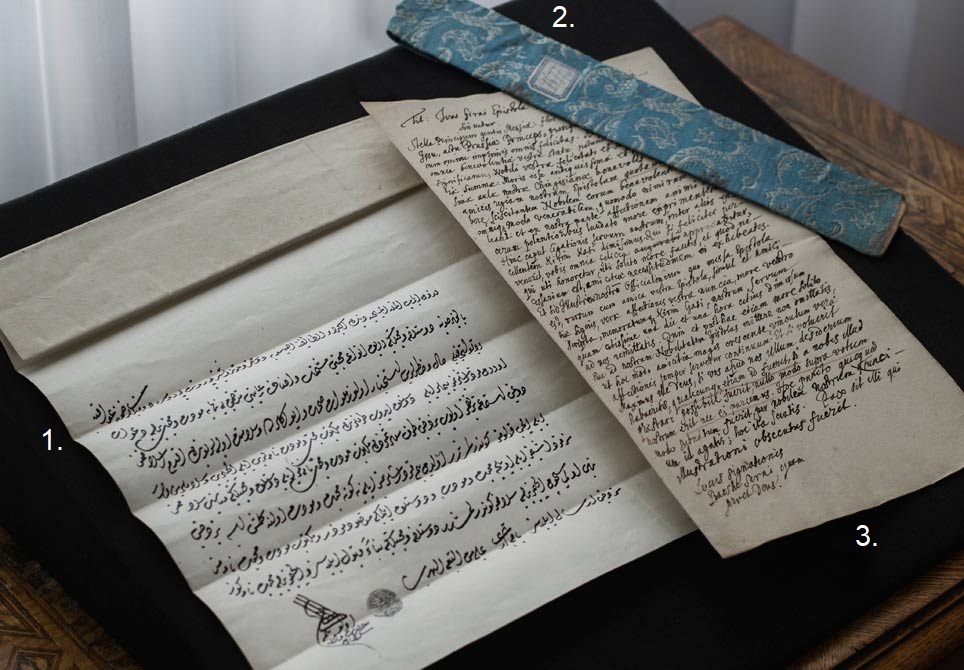

Another example of this outreach was the wonderful evening initiated by the Guatemalan Embassy in Berlin and Carlos Alberto Haas, a Guatemalan historian at the University of Munich, together with the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation). In the middle of Room 207, in front of the magnificently illuminated steles, lectures were delivered to a large number of assembled guests regarding the historical context and the imagery of the monuments, as well as their origins and the meaning attributed to them today in Guatemala. The monuments of Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa are, after all, part of Guatemala's indigenous cultural heritage, and that heritage makes itself felt in the present: to this day, parts of the indigenous population live in poverty, politically marginalized.

But how exactly did the monuments end up in Berlin in the first place? They were found near the town of St. Lucía Cotzumalguapa, after which the culture is named, in and around three fincas (country estates): Bilbao, El Baúl and Castillo. They were discovered when the plantation owners began to clear the land in preparation for planting cotton, sugar, and later, coffee. When Adolf Bastian, one of the founding directors of the Royal Museum of Ethnology, heard about the finds, he traveled to Guatemala himself in 1876 and acquired most of them for the museum’s collections. Additional objects were given to him by the plantation owners. In an essay concerning the acquisition, he wrote: “...when they were clearing the forest to plant crops on the haciendas, they came across these antiquities everywhere, so they have only recently been uncovered... moreover, some curious visitors have already begun to mutilate them, insofar as the rock allows, starting, as usual, by knocking off the noses. So it is high time that they be put in a museum for safekeeping." As this passage indicates, parts of the local population had already begun to repurpose material from some of the monuments. Bastian believed that by taking possession of them, he was saving them from vandalism.

He enlisted the help of German diplomats and engineers, as well as a scientist who died soon thereafter, and had the objects transported to the coast. This was a difficult undertaking and had to be accomplished with ox carts. The sculptures were brought to Germany by ship, with the first steles reaching Berlin in August 1881. When preparing the monuments for the journey, however, Basian and his men were not overly scrupulous. To reduce the weight of these colossal stones, the reliefs were cut off and hollowed out, resulting in further damage. During the last shipment, in February 1886, a particularly severe mishap occurred: a valuable relief depicting a bird fell into the water during choppy seas in the Pacific port of San José. To this day, it has not been recovered. It lies there still, at the bottom of the sea.

The problematic history revealed in historical documents plays a large role in the new exhibition. Fractures in the stone were deliberately exposed on the advice of conservator Kai Engelhardt. When the steles were on display in Dahlem, these cracks and the seams between the reliefs and stone backing were concealed, but the material that covered them has now been removed. This serves as a reminder that, contrary to what is often stated, museums did not always view the integrity of the objects they collected as their highest priority. The way the monuments at Santa Lucía Cotzumalguapa were readied for their removal to Berlin differed little in its callousness from their treatment by segments of the local population, who were primarily interested in using them as building materials. "The museum is critically engaging with its history,” says Ute Schüren. “We are also concerned with identifying instances of injustice, for example in the context of provenance research on the collections. By no means are all of the objects looted artifacts from colonial contexts, however. The objects have many different stories behind them."