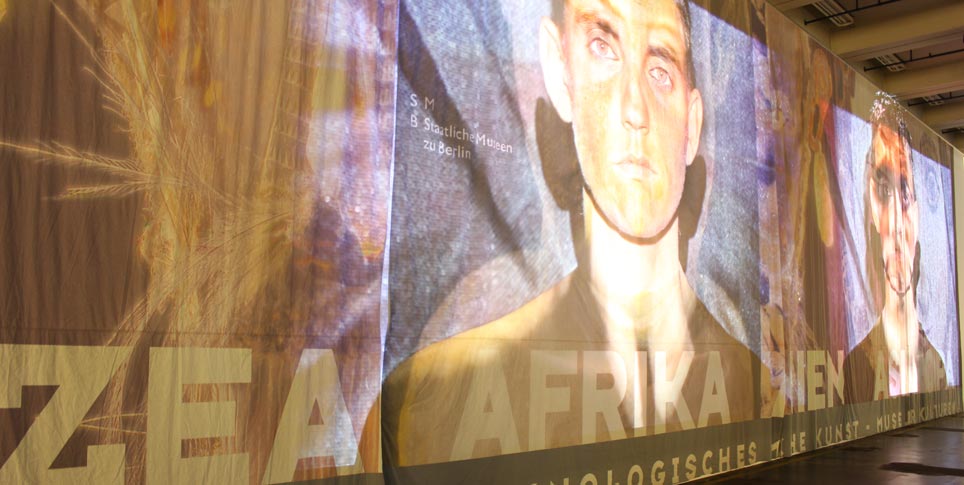

How cooperation with partners from Namibia has influenced the exhibition at the Humboldt Forum: an interview with Julia Binter, provenance researcher at the Zentralarchiv (Central Archive) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) and head of the cooperative project on the collections from Namibia at the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum)

Ms. Binter, the rooms of the Ethnologisches Museum are opening now at the Humboldt Forum. What will the exhibition show about Namibia, the former colony of German South West Africa?

Julia Binter: The exhibition gives visitors an insight into the ongoing research process which has grown out of a close cooperation with our Namibian research partners – first and foremost, with the Museums Association of Namibia. The goal of this cooperative project was to establish a research process which is as open as possible, with consideration for the needs and interests of everyone involved. We on the Berlin team felt we had a responsibility to understand the colonial contexts in which the Ethnologisches Museum acquired the nearly 1,400 objects from Namibia that are now in its collection. It was especially important to us to analyze whether there were any objects directly connected to the genocide perpetrated by Germany against the Ovaherero and Nama from 1904 to 1908. At the same time, it was also important to our research partners – among them scholars, curators and artists – to think about the future of the objects.

Nehoa Hilma Kautodonkwa, Cynthia Schimming and Julia Binter in the depot of the Ethnologisches Museum Berlin. Filmstill from „Tracing Namibian-German Collaborations“, a film by Moritz Fehr © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin 2020

What did they suggest?

Binter: They had ideas right away about what could be learned from the objects, how they could be dealt with in creative ways. Our discussions and exchange of ideas were so intense and to some extent emotional that we quickly realized we didn't want to show any original artifacts at the Humboldt Forum. Instead, we would focus on our joint research process: What does it mean to work with artifacts that in some cases were acquired in extremely violent circumstances? As a provenance researcher, what information can I reconstruct about the origin of objects and their historical relationships from the European archives, which are by their nature very one-sided? What historical and cultural significance do our research partners attribute to the artifacts? What personal experiences have they linked to the objects? And what can be done with them in the future?

What does that mean for the exhibition in concrete terms?

Binter: The exhibition consists of three parts: On the one hand, there is a film by Moritz Fehr, which provides a perceptive look behind the scenes. Fehr is a Berlin-based film maker, and he looked over our shoulders during our research on the artifacts in the storage rooms of the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin. He also traveled to Namibia with us, and his camera captured the ways in which the country's colonial past is still omnipresent – from German street names to the anonymous mass graves resulting from the genocide. So his film also shows how German colonial history has shaped not just the collections in Berlin but also the country of Namibia and the everyday life of the people there to this day.

What else can visitors look forward to?

Binter: We searched for a way to symbolize our intense discussions and sharing of knowledge, and hopefully, we have found one: it takes the form of a “network of knowledge.” We used pieces of leather and fabric to “weave” a network, and attached to that are photos of some of the twenty-three artifacts from the Namibia-collection of the Ethnologisches Museum that our partners have asked us to bring to Namibia for further study next spring. Visitors can see our network in a display case at the Humboldt Forum. The installation shows what we gain when we are responsive to the needs of our research partners, when we let go of artifacts and let them travel. We gain so much – so much knowledge, appreciation and mutual understanding. In addition to the pictures of artifacts, there are historical and contemporary photographs woven into the network, along with a whole variety of voices on text panels. The installation rejects the simple consumption of beautiful things, focusing instead on people and their relationships to objects. I am excited to see how visitors respond to it.

So the exhibition really doesn't show any artifacts from the Namibia collection of the Ethnologisches Museum?

Binter: No, they weren't shown in Dahlem either. Our partners rightly asked why the artifacts should be shown at the Humboldt Forum now, of all times, when there are so many people in Namibia who, for historical and cultural reasons, have developed an interest in working with them and caring for them. In 2019, our Namibian colleagues visited Berlin for several months to conduct research and they selected twenty-three historically, culturally and aesthetically important objects for further study – in the course of many discussions with experts at home, interest groups and representatives of a wide variety of organizations. The objective is to revitalize the artifacts in Namibia with the knowledge of community members, artists and scholars there. And it is only thanks to support from the Gerda-Henkel-Stiftung (Gerda Henkel Foundation) that we are able to carry out a follow-up project at this scale.

What sort of artifacts are these?

Binter: A large part of the Namibia collection in Berlin consists of articles of clothing and jewelry. That means they are more than just testimony to historical events and relations. Our Namibian partners also view them as a source of inspiration for the creation of new fashion designs and works of art. It is a wonderful development that the Museums Association of Namibia will soon open the new Museum of Namibian Fashion in Otjiwarongo, where historians, fashion designers and community representatives will be able to use clothing, amongst other things, to confidently talk about the histories and the identities of Namibia in a new way. And the sources of inspiration for that include historical artifacts not just from Berlin but also from collections at the National Museum of Namibia in Windhoek. So we're bringing a variety of insights from the past and the present together and combining them – and, thus, creating something new.

And now let’s hear about the third part of the Namibia exhibit at the Humboldt Forum.

Binter: It's a textile-based work of art by Namibian fashion designer Cynthia Schimming, who looked at the Dahlem collection with us in 2019 and explored its potential for future projects. From the very beginning, she viewed our collection as an archive of Namibian design and fashion history; one time she remarked, “You talk so much; I prefer making things.”

What does this work of art look like?

Binter: Schimming's work consists of two parts, which allow us to understand the body and landscape as sites of colonial experiences. She has created a Herero dress, which incorporated her research into precolonial fashion. The pattern is modeled on Victorian dresses, with puffed sleeves and a wide underskirt. Along with it, there is a headgear that imitates the shape of cow horns and alludes to the proud history of the Herero as cattle breeders. The second part of the installation focuses on another key object in the collection: a leather patchwork blanket made by Nama artists. The blanket was part of the personal effects of Gustav Nachtigal, which were given to the museum in Berlin in 1886. Nachtigal was Reichskommissar (Imperial Commissioner) of the German colonies in West Africa. He probably acquired the blanket when he concluded so-called “protection treaties” with Nama representatives. Schimming has transferred the design of this patchwork blanket to a long panel of fabric and printed it with historical photographs from our archive. The result is really impressive. The work illustrates her philosophy: history isn't just something that we ought to write down and understand; wherever we go, we also carry history with us.