On the trail of the Aztecs: In the "Manuscripta americana" exhibition, the Stabi Kulturwerk takes us back to the early colonial era and pays tribute to the indigenous cultures of Latin America. The pictographic manuscripts that Alexander von Humboldt brought back from Mexico form the centerpiece.

What is a comic? Well, the quick answer might be “a medium of expression that became popular in the 20th century.” Of course, in earlier eras too, images and text were combined to tell stories, but it was only with the advent of Disney and Marvel comics that this narrative method finally became popular – and Donald Duck conquered the world.

But now, in the Stabi Kulturwerk, the wonderful treasure chamber of the Staatsbibliothek (Berlin State Library), you can see for yourself that the genre actually has a long history, and we moderns are not quite as innovative as we might like to think. In fact, a form of comic existed in Latin America as early as the 16th century.

Photo: Exhibition view: The god Quetzalcoatl, green-feathered serpent and inventor of writing, merges here with Ehecatl, wind (left). Next to it, an alabaster monkey from the Teotihuacan culture (right). © Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin-PK

The special exhibition "Manuscripta americana. On the Trail of the Aztecs" supplies proof of that in the form of some precious exhibits from the collection of Alexander von Humboldt – "a few of our prize pieces", as curator Angelika Danielewski proudly comments. These "Humboldt fragments" are a very heterogeneous collection, comprising original indigenous manuscripts as well as copies. They come from communities in central and southern Mexico and were the main source of material for the European scientific study of that cosmos. In the course of his research expedition to the Americas, Humboldt visited Mexico in 1803–04. The indigenous art and culture that he encountered there inspired both his curiosity and his admiration, and he recognized it as part of the human heritage that needed to be understood and preserved. This distinguished him from the majority of the incumbent Spanish colonial officials, who had no respect for the Aztec civilization, labeling it "barbaric" and treating it dismissively or even with contempt. The systemic battle of cultures that unfolded in the course of colonization can be found as a structural element in many of the fragments in the Berlin exhibition.

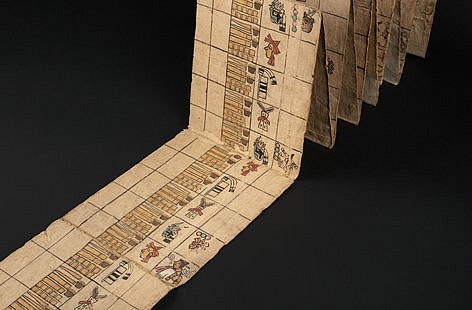

The emergence of this "early comic form” had a very practical reason. Since numerous ethnic groups lived close together in Latin America, the Aztecs used a pictorial script that had originally been developed by the Mixtecs (Mexican natives from the Mixteca region). Based on commonly understood pictures, symbols and hieroglyphs, such as the calendar signs that had been in use for centuries in large parts of Mexico, it enabled rapid communication across language barriers. The written documents were often folded into leporellos (screenfolds) to which new pages were glued when necessary. They can be read from top to bottom and from left to right, or in a zig-zag direction (boustrophedon). As for the content, the main themes that emerge are those of exploitation and resistance, land ownership, cadastral sheets, the struggle of the indigenous elite for their social and political position, writs of complaint before the courts, and Christianization.

Open to the public in its entirety for the first time

The oldest fragment, a register over four meters long (Codex Humboldt Fragment 1), is particularly elaborate. It was probably created 500 years ago in the former kingdom of Tlapan-Tlachinollan on the Pacific coast of Guerrero. It lists the tributes to be paid to the Aztecs between 1504 and 1522, such as woven clothing, gold dust, and hammered gold plates of various sizes and shapes. Several columns of pictograms vividly portray, in a generally accessible form, the goods and quantities to be delivered.

Another tribute list from the province of Tlapan demands 400 gourd shells for cocoa, 10 whole gold sheets, 20 shells of gold dust, 400 cross-striped blouses, 400 lengthwise striped coats, 2 x 400 white coats, a Xipe warrior suit with shield and a Jaguar warrior suit with shield. Dynastic events and the arrival of Aztec officials are also recorded, as are places newly incorporated into the tribute province. The Spanish conquest in 1521 saw the beginning of the colonial era in Mexico and the end of such tributes; Mexico was renamed New Spain and the Aztecs themselves were forced to pay taxes to their new masters.

Another fine example of the use of image and language is the "Codex Vindobonensis Mexicanus 1" (a facsimile – the original is in the Austrian National Library in Vienna). Created by Mixtec artists in southern Mexico, it came to Europe as a gift from the Aztec ruler Motecuzoma [Moctezuma] II. It tells the story of the god Quetzalcoatl, who the Mixtec called "Nine Winds" in accordance with the day-sign of his birth. Splendidly colorful and wonderfully detailed, one side depicts Quetzalcoatl descending to the earth, the other side shows him lifting the sky from the floods.

The art of the pictogram was taught in the temple schools, which were primarily attended by the sons of the aristocracy, but on occasion, also by individual girls.

In 1806, Humboldt donated his collection to the Königliche Bibliothek zu Berlin (the Berlin Royal Library), the predecessor of the Staatsbibliothek. The artifact collection was first exhibited in 1892, on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus. It has had an eventful journey. Most recently, during the Second World War, part of the collection was evacuated (as were many other objects) to remote, safe locations outside the capital. A part still remains in the Biblioteka Jagiellońska in Kraków. As part of a project organized by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation), these Manuscripta americana have been restored and digitized and the physical materials analyzed, and they can be studied at a multimedia station in the exhibition. For the first time, they are being made accessible to the public here in their entirety, in a combined digital and material form.

Interplay between materials research and cultural history

The Bundesanstalt für Materialforschung und –prüfung (BAM, the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing) played an important role in this very worthwhile process. In conjunction with the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, they set about answering the following questions: Where exactly do the manuscripts come from? How old are they? Which parts belong together and in which order? Can they be assigned to certain artists or workshops? At the beginning of the 20th century, material analysis was already a valuable resource in the effort to differentiate and decode indigenous codices. As techniques underwent immense improvement over time, material-based scientific research began to complement cultural-historical research and allow a more precise, more thorough examination of existing artifacts. It could thus be confirmed that certain fragments belonged together. The material analyses made it possible to define the different inks and their element admixtures, as well as the adhesives and coloring agents. For example, in a partial copy of the Codex Aubin – on European paper – the contours were executed with soot-based ink, while ochre, vermilion, indigo and zacatlaxcalli were used as color pigments, and iron gall ink for the script itself. By contrast, the Humboldt fragments and the village book of San Martín Ocoyacac from the Uhde Collection used Amate paper, which was made from fig-tree bark, soaked and boiled with the addition of lime and ash. The fiber strands of the bark were laid out in a grid and joined together by tapping them with a grooved stone. The resulting sheets were then dried in the sun and, if necessary, lightened with lime water before being written or painted on. To glue them together into folding books, a starchy mass was made from the root tubers of orchids.

These legal and economic documents, tokens of the cultural practices of memorialization used by their authors, are an invaluable aid to understanding the social and political processes in the early colonial period of their countries of origin. They are eye-opening in a sense that accords with Alexander von Humboldt’s personal creed. During his travels through large parts of the Spanish colonies in South and Central America from 1799 to 1804, he saw the Pacific Ocean for the first time in Peru and wrote in his diary: “There was always some mountain range that obscured our view, although we made every effort to continue our ascent. It is all very reminiscent of the intellectual or moral world where one ascends to general principles from which all else seems to proceed; yet notwithstanding, we constantly come up against something which obstructs our view. Happy is the person who recognizes their limits and does not mistake the clouds for the horizon they are seeking. Therein lies the basis of our entire philosophy.”