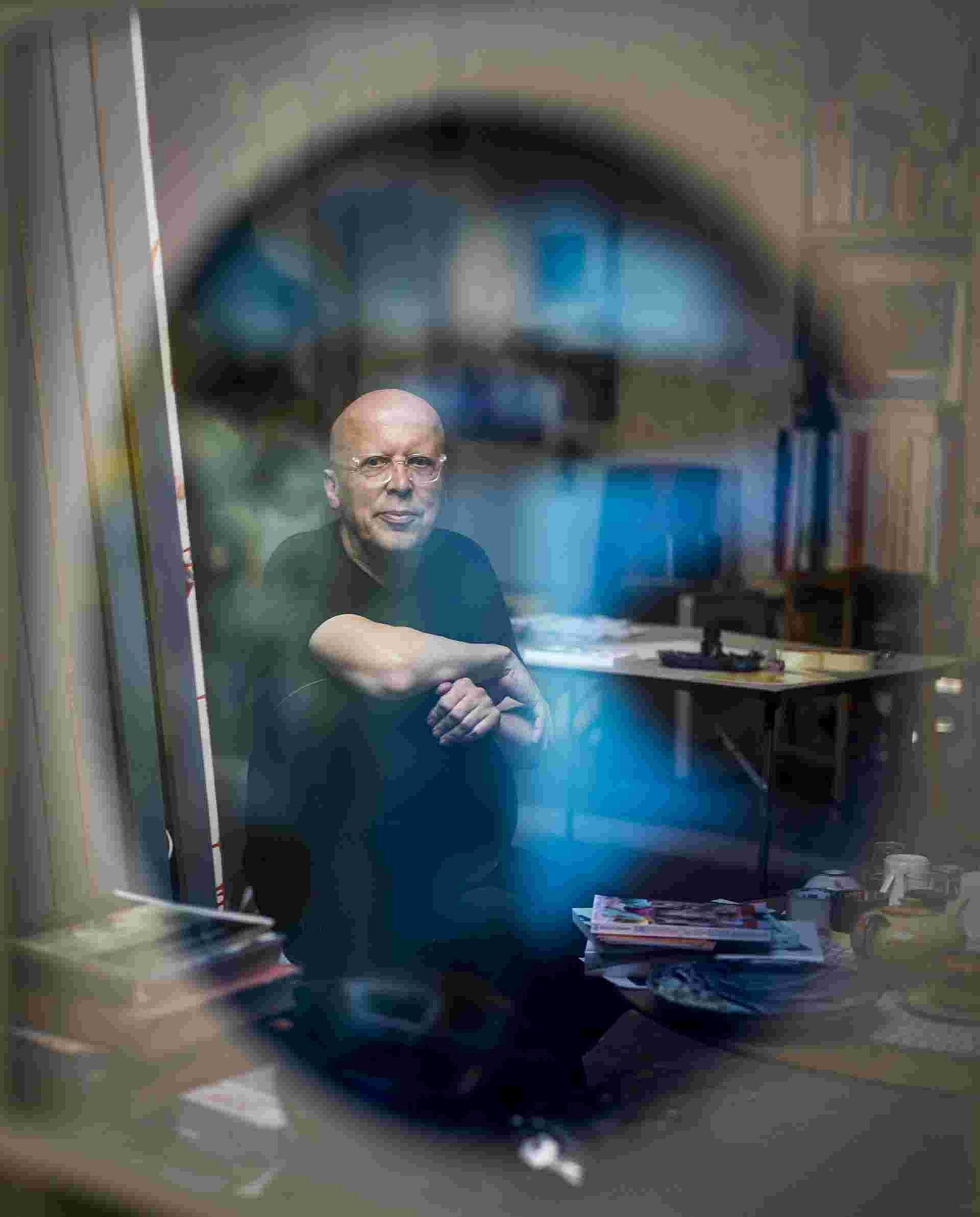

Pop and socialism, awakening and anarchy – such were the contrasting themes that shaped the early years of painter Klaus Killisch. Born in the town of Wurzen, Saxony, in 1959, Killisch studied painting at the Berlin-Weissensee Art Academy. His neo-expressive style and his subjects, which were inspired by punk, rock and pop, were considered subversive in the GDR. Even today, he draws inspiration from the theme of transformation. One of his most important works is now being shown in the new permanent exhibition of the Hamburger Bahnhof.

In his interview with the SPK, Killisch talks about the art scene in East Berlin during the 1980s and the significance of his East German socialization. He also shows us his electric guitar, which he built himself at the age of fourteen.

Der entfesselte Zuckermann from 1987 is one of the most prominent works in the new permanent exhibition of the Hamburger Bahnhof. How do you feel about this presentation of your work and the new approach being taken to Berlin's art by the Nationalgalerie der Gegenwart (National Gallery for Contemporary Art)?

I was very happy the picture was chosen. Ten years ago, a Swiss art collector donated five of my works to the museum. At the time, my first thought was that I probably wouldn't see the pictures again and they would disappear in the storage rooms. It was a big surprise that the picture is being displayed so prominently. I like the presentation and the new permanent exhibition.

The architecture creates spaces where dialogues can take place and there are invariably unusual insights into Berlin's international art. I think it's a brilliant idea, in comparison with a conventional hanging. And the concrete and steel are exciting materials. My picture fits into this setting well. I'm also happy to have it hanging across from Kippenberger and Fetting. There is a Dan Flavin next door, and in the distance, if you cast your glance to neighboring areas, you can see a Rauschenberg and a work by Isa Genzken.

In general, I think Berlin needed an exhibition like this, where you can get an overview of the city's artistic output. It's nice that questions are being addressed: Who were the artists here who influenced the city and its history?

How did this painting come about?

I've thought about that many times in recent months. The picture is from 1987. That was a special year for me, because I traveled to Kiev at that time. Suddenly, it was very easy to go there, because Chernobyl had happened a few months before, and all the Western tourism had collapsed. That meant there was an unusual opportunity for us, for me and the artist Sabine Herrmann, to make a trip to Kiev.

We weren't even aware of the hazard there shortly after the nuclear disaster. We went mainly because the glasnost movement had just begun there, as in the rest of the Soviet Union. That was fairly exciting. We saw large demonstrations, critical speeches and performances, and there were the first films critical of the war in Afghanistan and the Soviet leadership, like Juris Podnieks's documentary Is It Easy to Be Young?

That was when I first had the feeling that the society and the environment in which I grew up wouldn't remain the way it was. That something was starting to falter. And that's how Zuckermann came about – this man tilting his head with his ear upward, listening.

That was a time, as you just described, when people saw the Festival of Soviet Film in a completely different light. Films were banned overnight, because they were so subversive.

Yes, or the magazine Sputnik, which was suddenly illegal in the GDR.

The ceramics workshop of Wilfriede Maass was one of the major meeting places for artists and intellectuals in the GDR opposition, and you were deeply involved in that scene. Was this a time, in your perception, that gave you some freedom and scope for development, despite all the repression?

The late 80s and then the 90s were an incredibly important time for me and my generation in East Germany. In the 1980s, it felt as though there was no longer this pressure from above. For example, the state doctrine that art had to be propaganda and convey ideology. Instead, I had the impression – which later turned out to be wrong – that the state took no interest in us, at least not in the artist circles of East Berlin.

Our generation no longer had this ideal of wanting to reform socialism. We just wanted to do our own thing and pursue our independent projects. The contact with Wilfriede Maass developed during this phase. At the end of the 80s, one of the first artist-run galleries was founded in her ceramics workshop. There were always exciting encounters there.

The ceramics workshop was a meeting place for many authors and painters who were headed West or were passing through. There was also a lot of give and take with artists from Eastern Europe – people from Georgia, for example. We just wanted to collaborate as artists or even set up an art center, which of course didn't work out in the East.

One senses that music plays an important role in your pictures. What bands did you listen to back then, and what was happening with punk in the late GDR?

We were able to tune in all the broadcasters from the West, including the anarchistic pirate stations, like Radio 100. We were always recording music on cassettes. Through contacts, we got the latest records from West Berlin. Now that I have a BMW from the 80s with a built-in cassette player, I can listen to those old recordings again.

Music really did play a major role. For example, the music of the "other bands" in the East, like Ornament and Verbrechen. But the Einstürzende Neubauten and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds had a big influence on me too. I named many of my pictures after their songs.

Was there interaction with artists from the other side of the city, too, from West Berlin?

There were a few artists who came over – the performance artist Käthe B, for example. He had the idea of offering a performance wherever there was a square or a street with "Käthe" in its name. There were a number of places like that in East Berlin. Christoph Tannert, who now manages the Künstlerhaus Bethanien, brought him over there.

We were well informed about developments in West Berlin and Western Europe, and we knew what was happening in Eastern Europe, too. Closer contacts developed only later, in the 90s, when it was possible for us to travel.

In the 90s, close personal contacts were also formed with artists in the United States. We set in motion a project back then called Collective Task, which still exists today.

What is Collective Task?

I have a friend from New York who came to East Berlin in 1989 – Robert Fitterman. He was an important figure from a very specific group of authors in New York, the "Language poets." Robert was very interested in what was happening here. We met in the gallery at Wilfriede Maass's place. In 1991, we took a trip together across the United States. That resulted in a book of artwork with his writing. That was the beginning of our collaboration and friendship.

The collective has been around now for ten years. It was Robert's idea that we should invite some artist friends to form a group now and then, with the members changing each time. One of the artists sets a task for the others, and then each member of the group has a month to complete the task in whatever medium they choose. That's quite motivating. We're now in the fifth cycle, and we were even invited to perform at the MoMA in New York. Everything takes place online, and the project has its own website too.

Does your East German background play a role in your art?

At first, I thought we were part of this great global community of art. But then in the 90s, there was this differentiation, which was mainly asserted by artists from the West. There were various reasons for that, some of which have to do with the way the art market works. The East German background became such a big issue. Where you came from was even mentioned all the time in the press, even if you didn't want to make that a subject of discussion. I have no problem with my background, and I'm quite happy to have the biography I do.

It's important to me that I experienced the end of the GDR, that I was part of the movement that led to the fall of the Berlin Wall. I often notice that artists who left before 1989 and didn't share that experience have a very particular, difficult feeling. The sense of a positive conclusion is missing somehow. I had the chance to be part of the Peaceful Revolution. What sort of view you take of all that is a different question, of course. Every life is different, and each person experienced that era in their own way.

Over the years, the city of Berlin has changed. Has that influenced your painting too?

Yes, absolutely. At the beginning of the 90s, I noticed that I wasn't content with the sort of painting that I developed for myself in the 80s. It didn't quite fit anymore. During that time, I did a lot of searching, and Berlin was the big sounding board for that.

What sort of experiences did you have with that?

There were impressions that caused me to call a lot of things into question. What do I actually want to express with painting? That was my biggest thought. I've always been interested in the fine line between art and pop, including advertising. I've been happy to take in those influences.

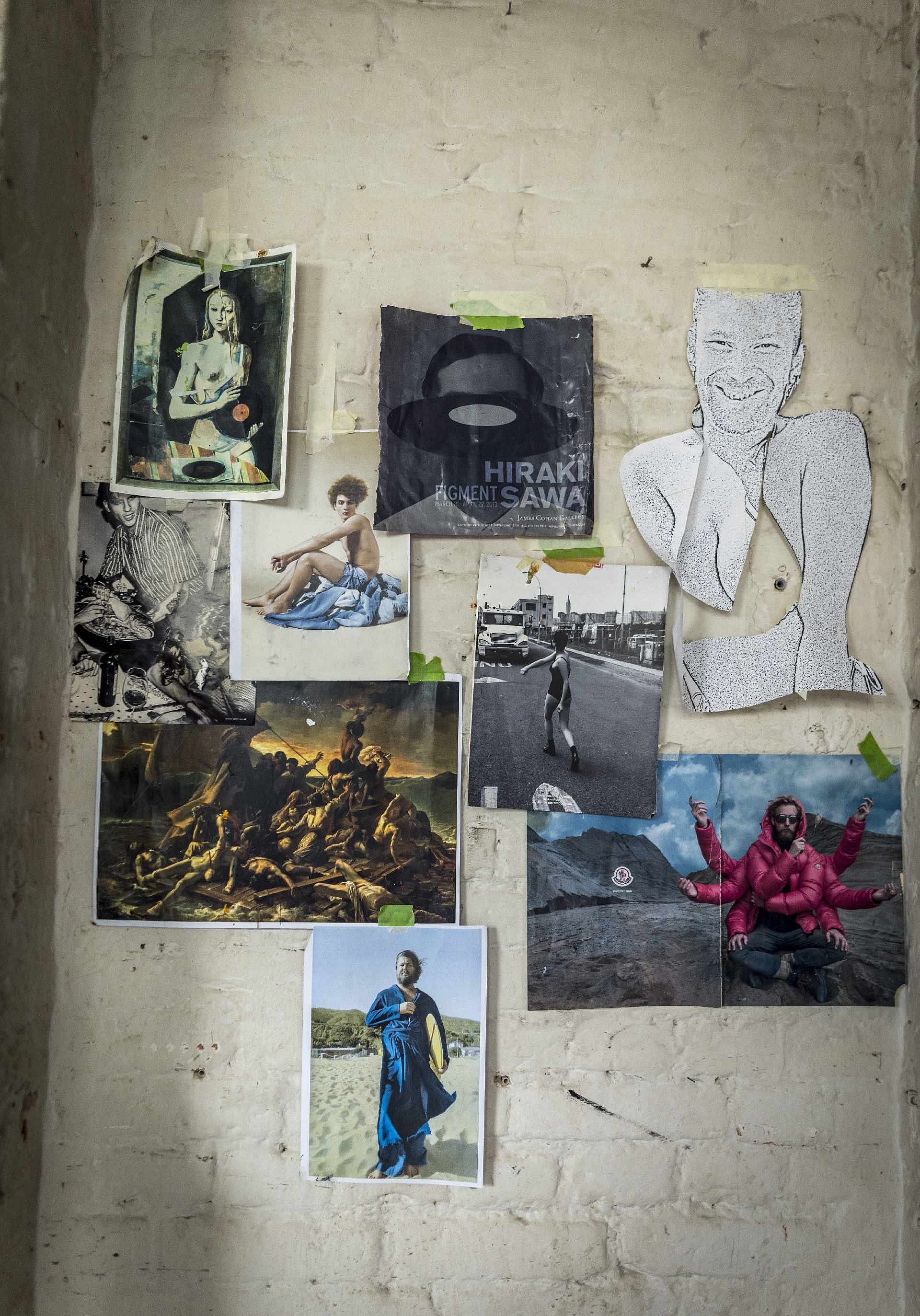

In the 90s, a friend of mine named Sangare Siemsen opened Café Silberstein in Oranienburger Strasse, Berlin-Mitte, and later the bar "ambulance." He asked me whether I could make a large ceiling mural for his bar based on the collection of records he had played as a DJ. Working with this material from the clubs of the early 90s was very exhilarating. Based on that experience, I developed the collage technique in my painting. It's important to me that there's development in the studio and that you're going in your own direction.

Has the city changed for the better or the worse?

What bothers me is that what made the city attractive and internationally famous is currently disappearing. There were free spaces for all types of artistic activity, areas for creative projects and exhibitions, and art studios, but now the leases for those spaces are being terminated in waves, especially the studios.

The international art scene that developed here, the artists who made whole neighborhoods attractive, are now being driven out. All the same, I find it surprising that there are still niches here, that new exhibition rooms are being opened, and that there still seems to be great potential.

The exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof is in part a journey into the recent past, with many moments of longing and many political works. Do you see yourself as a political artist?

I'm not an activist or anything. I'm interested in politics, and I think every artistic statement that reaches the public is a political statement.

How about the period when the Wall fell?

Yes, then too. In the 80s, I was part of the church-based peace movement, and that caused me problems at the art academy in Weissensee. In the period of upheaval around 1989, we were on the street demonstrating.

How did you first become interested in a career as an artist?

The father of a friend of mine collected a lot of science fiction books from the West during the 1950s. There was one series called Utopia, and I found the painted cover illustrations incredibly exciting. I traded these issues with my friend, then I enlarged the covers and painted them to no end. I was twelve or thirteen years old at the time. Unfortunately, I don't have these pictures anymore, but they were the decisive input.