Gabriele Kaiser and Katrin Böhme are curating the exhibition "Die Vogel-WG" at the Stabi Kulturwerk. The exhibition tells the incredible story of Oskar, Magdalena and Katharina Heinroth, who raised and scientifically researched the chicks of 250 different bird species in their Berlin rented flat at the beginning of the 20th century - from the tiny wren to the giant white-tailed eagle. The two scientists answer your questions here

How were the animals and their behaviour researched beforehand? And do we know how the Heinroths came up with the idea of keeping birds in their home? Where did the birds come from?

Ornithology in the 19th century as part of natural history can be described primarily as a collecting science, in which the knowledge or description of species and their relationships in the sense of a systematic order were at the centre. Questions about communication or species-specific behaviour were unknown at that time. One of Oskar Heinroth's pioneering achievements was to look at behavioural patterns - in his specific case using duck birds - from a species-specific point of view. He recognised that behavioural patterns differed from species to species and that these patterns, like morphological or anatomical characteristics, provide information about phylogenetic relationships. In one of his earliest works on this subject, he used the term "ethology" for comparative behavioural research for the first time.

The birds were mostly reared from the egg, i.e. initially by "incubation", and later in a self-developed incubator. Magdalena and Oskar took the eggs from the birds during their numerous excursions into the Berlin countryside and far beyond.

At the beginning of the 20th century, searching for nests and collecting eggs was common scientific practice in ornithology. The trade and keeping of wild birds was also part of everyday life. Driven by a passionate interest in ornithology and the life of birds, Magdalena's initial hobby turned into a long-term and energy-sapping project. At the end, after 28 years of breeding work, there are more than 250 species in around 1000 bird individuals and a four-volume book that marks the beginnings of behavioural research in Germany.

Research QUESTIONS

How do you actually restore paper? How do you recognise whether a painting is genuine? And how do you play Beethoven properly? With the Research QUESTIONS, we give you the opportunity to ask us your questions. In each issue of the research newsletter, a researcher from the SPK answers selected questions from the community on a specific topic.

What about animal welfare? Is it even possible to keep so many different birds in one flat in a species-appropriate way? And what did the Heinroths' landlord say?

To be successful in keeping and rearing birds, you need an environment that meets the animal's needs. Otherwise the animal would die. The large number of bird species shows that the Heinroths were able to create species-appropriate conditions. For example, the dipper, which in nature lives by flowing water, had a small stream in its cage. The swift spends its life in the air; it eats, sleeps and mates during flight. At the Heinroths', a so-called swift home was set up for it, which allowed it to rest for short periods. Otherwise it flew around the flat. The woodpecker pecked holes in the cupboard, while a treecreeper ran along the master's trouser leg. In other words, the animals perceived the domestic environment as their habitat and behaved accordingly.

With the breeding of nightjars, the Heinroths also became known beyond the country's borders. Nightjars are nocturnal birds that catch insects in flight with their wide-open beaks. Keeping and breeding them was considered impossible. Magdalena and Oskar had managed to raise young birds bought out of compassion at a Berlin bird market. And apparently the birds felt so comfortable with the Heinroths that they actually mated, bred and had offspring the following year. As if that wasn't enough, the first brood was followed by a second successful one, so that in the end the Heinroths were home to a further 6 nightjars in addition to the parent birds Kuno and Nora. The birds, which breed on the ground in the wild, chose a pigskin that was lying on the living room floor.

With the construction of the Berlin Aquarium, of which Oskar Heinroth was the director, they were able to move into an official flat there in 1913. Until then, they had lived in a rented flat in Berlin-Friedenau. The neighbours occasionally complained about smells and noises. Despite this, the research couple continued to keep the animals in the flat.

Didn't the unnatural environment and close contact with humans distort the animals' behaviour?

Even the Heinroths were confronted with this question! You can read their answer in the introduction to the first volume of "Birds of Central Europe". And to add to this: The Heinroths' precise observations and findings led, among other things, to the subsequent differentiation between instinctive, i.e. innate, and learned behaviour. Oskar and Magdalena described a number of phenomena for the first time, such as the imprinting of newly hatched chicks on the person present or the learning of song by listening to other bird songs. For example, the eider duck Edda, who hatched on the train home from Sweden and from then on recognised Magdalena as her first caregiver. Or the nightingale Ferdinand, who imitated parts of the song of a blackcap, as both were kept at the same time. The famous behavioural scientist Konrad Lorenz saw Oskar Heinroth as his most important teacher and later anchored many of these observations in scientific theories.

What discoveries did the Heinroths make that made a lasting impression on you?

It is not so much a single discovery that fascinates, but rather the passionate interest in bird breeding and the life of the birds, which determined the entire daily routine and the very unusual family life. During the annual rearing periods from spring to autumn, they kept around 30 to 35 bird species, all of which were given suitable food and whose cages or nests had to be kept meticulously clean to prevent disease. The dedication to the animals over a period of almost thirty years ultimately led to massive health problems for the foster parents, but these were accepted. The love and bond between Magdalena and Oskar was certainly a source of strength. Her precise powers of observation and detailed scientific documentation made it possible to gain insights into the individual development of bird species, their species-specific communication and behaviour, which marked the beginnings of behavioural research in Germany.

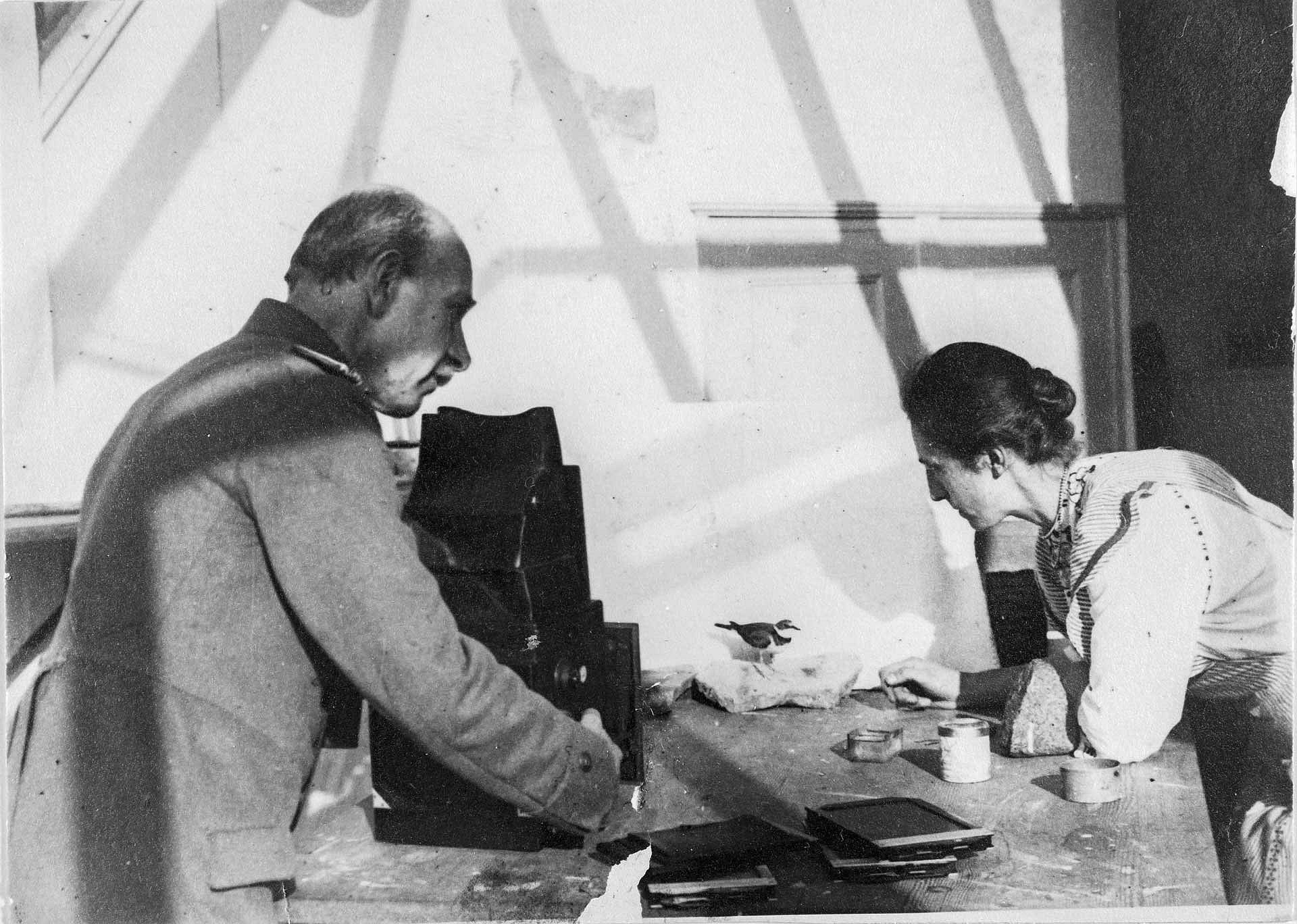

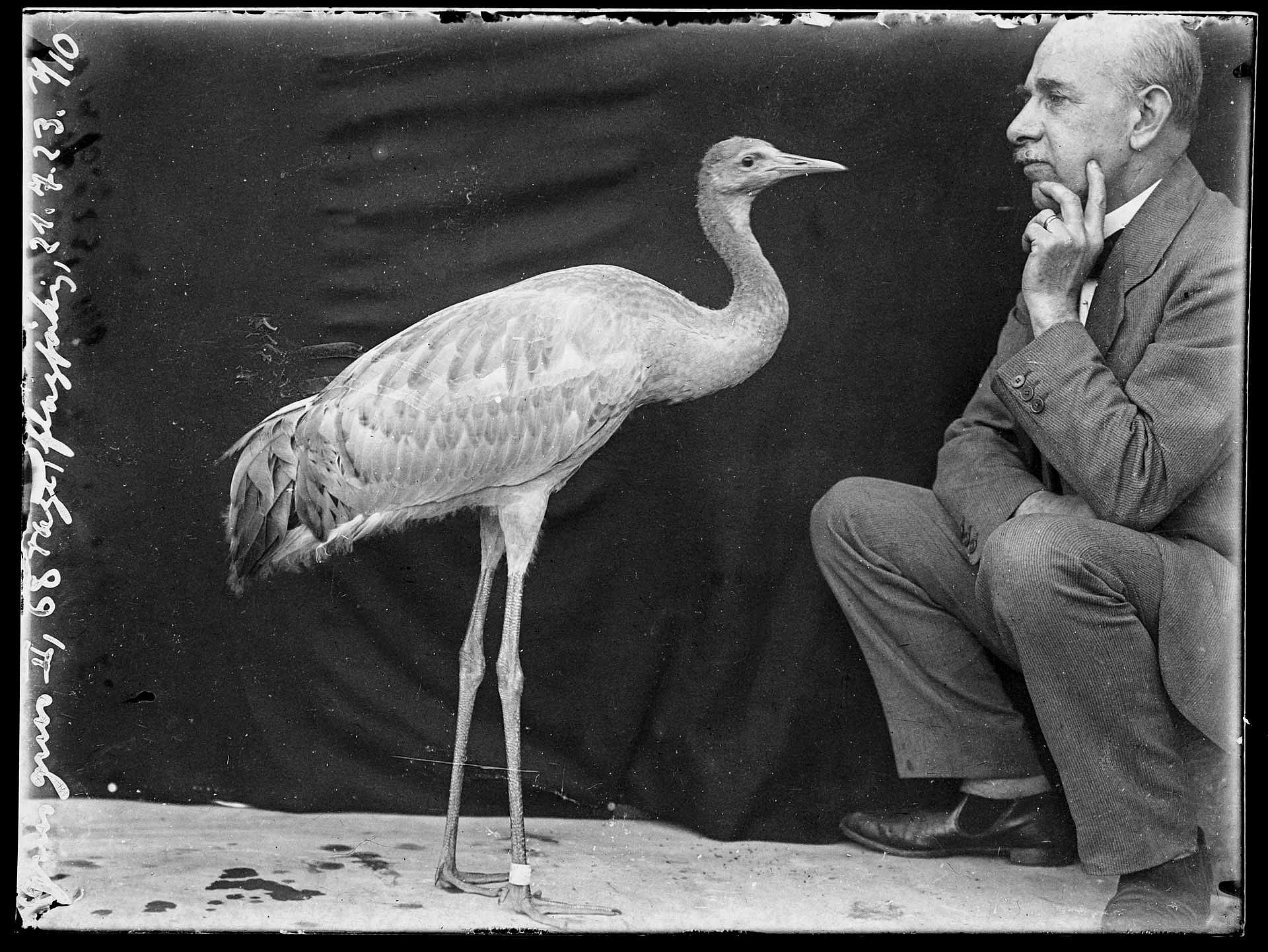

There are also thousands of photographs in her estate. Photographic documentation was part of the daily routine of bird breeding, with Oskar operating the plate camera and Magdalena taking care of positioning the birds - a task that was quite demanding, depending on the species. In some cases, several blank shots without a glass plate negative were necessary to get the animal used to the sound of the shutter release. In the end, however, they both managed the seemingly impossible: the birds even appear relaxed in the photos.

What role did Oskar Heinroth's wives, Magdalena (1883-1932) and Katharina (1897-1989) Heinroth, play? Katharina took over almost seamlessly after Magdalena's death. Are they particularly honoured in the exhibition?

The exhibition tells the story not only of Oskar, but of course also of Magdalena and Katharina, who are each thematised in their own showcases.

Magdalena was the soul of the bird breeders. Without her dedication, care and empathy, the whole thing would be unthinkable. She did most of the care work and was responsible for procuring the food, keeping the cages clean and feeding the birds. Oskar was not only fully occupied as an assistant at the Berlin Zoo, but also as director of the aquarium from 1913 onwards. Studying the birds was practically his hobby.

The numerous photographs show Magdalena as a young, self-confident and cheerful woman. The daughter of a middle-class family, she trained as a taxidermist at the Berlin Natural History Museum in Invalidenstraße. She obviously had the necessary willpower to pursue her early interest in animals professionally and to realise this unusual career aspiration. Incidentally, it was at the Natural History Museum that she met Oskar Heinroth.

Katharina was a biology graduate with a doctorate. Here too, their shared interest in ornithology and biology in general played a major role. However, the bird flat-share as a common place for the life and keeping of birds essentially came to an end when they finished work on the book "Die Vögel Mitteleuropas" (The Birds of Central Europe). Katharina researched the behaviour of pigeons, for which purpose a dovecote was set up on the roof of the aquarium.

The aquarium and the zoo were destroyed during World War II by bombs in November 1943, killing numerous animals. The descriptions of this in Oskar Heinroth's "personal report" are harrowing. Katharina had a very important task during this time, standing in for her seriously ill husband.

After the end of the Second World War, Katharina became Director of the Zoological Garden, making her the first woman ever to hold this position. Under her leadership, Berlin Zoo was rebuilt and became a crowd-puller in Berlin. Despite successful reconstruction work, she was dismissed from this position in 1957 following intrigues and disparagement.

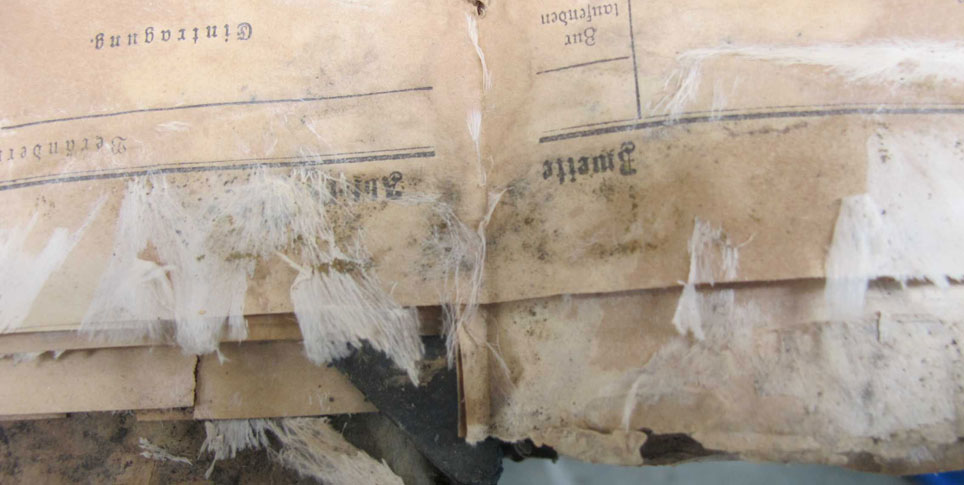

At the end of the war, Katharina Heinroth rescued Oskar and Magdalena's estate from the rubble of the aquarium, i.e. all the archive material that provides us with information about the “Vogel-WG” today, and handed it over to the Staatsbibliothek (State Library) in 1980. In doing so, she laid the foundation for the creation of the exhibition.

Special exhibition "Die Vogel-WG"

- 13 June to 14 September at the Stabi Kulturwerk

- Wednesday to Sunday: 10 am - 6 pm

- Thursday: 10 am - 8 pm

- Monday and Tuesday: closed

Admission free!