Benedikt Brilmayer is a research associate at the Musikinstrumenten-Museum of the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung. In the interview below, he answers questions about electronic musical instruments, the “New Music” and the relative value of a Beethoven violin.

What sort of challenges do electronic instruments represent for a museum collection, and should or must the instruments in the collection actually be played?

Surprisingly, electronic instruments pose a great many challenges in the context of a museum collection. The reasons for that are complex, and they have to do with the specific material qualities of the objects involved. In the case of musical instruments, an additional question – which should not be underestimated – is the matter of playing the instrument and generating its characteristic, ephemeral sound, which is an important aspect of the identity of the object.

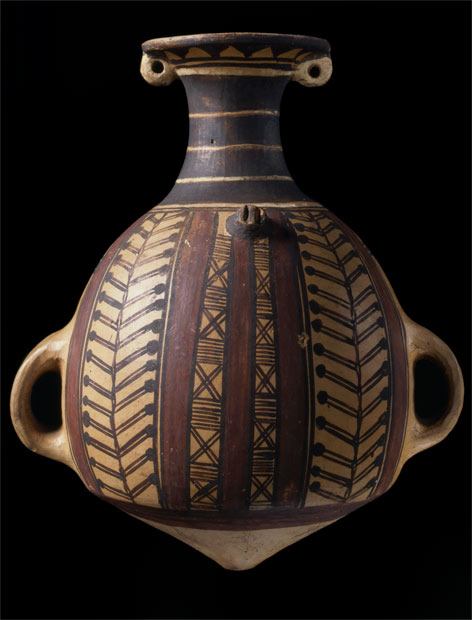

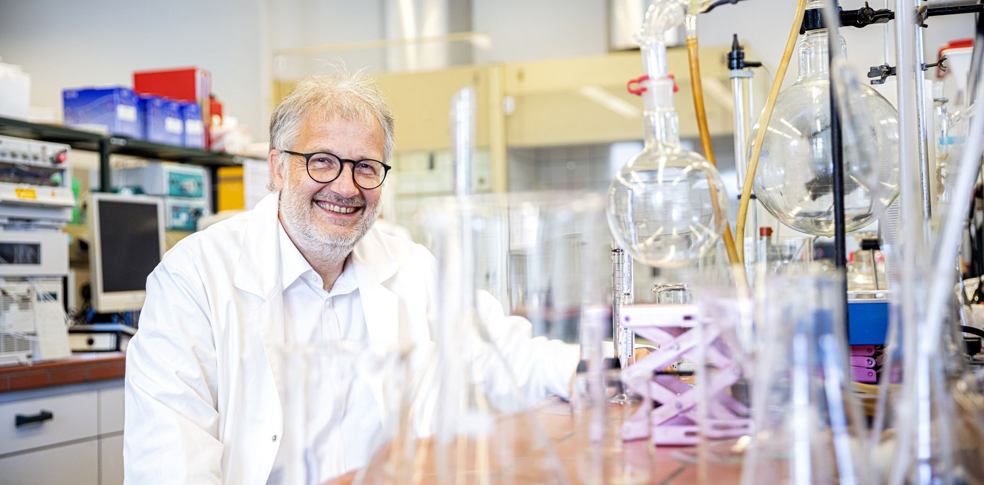

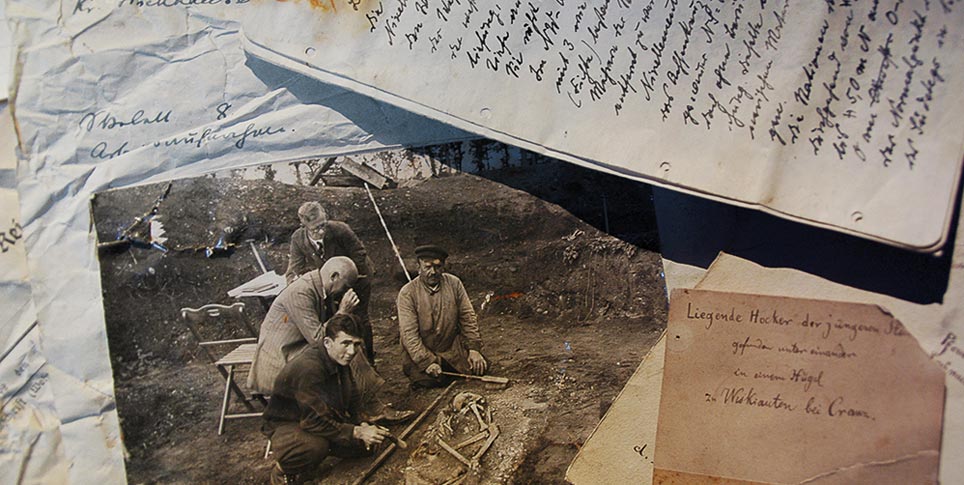

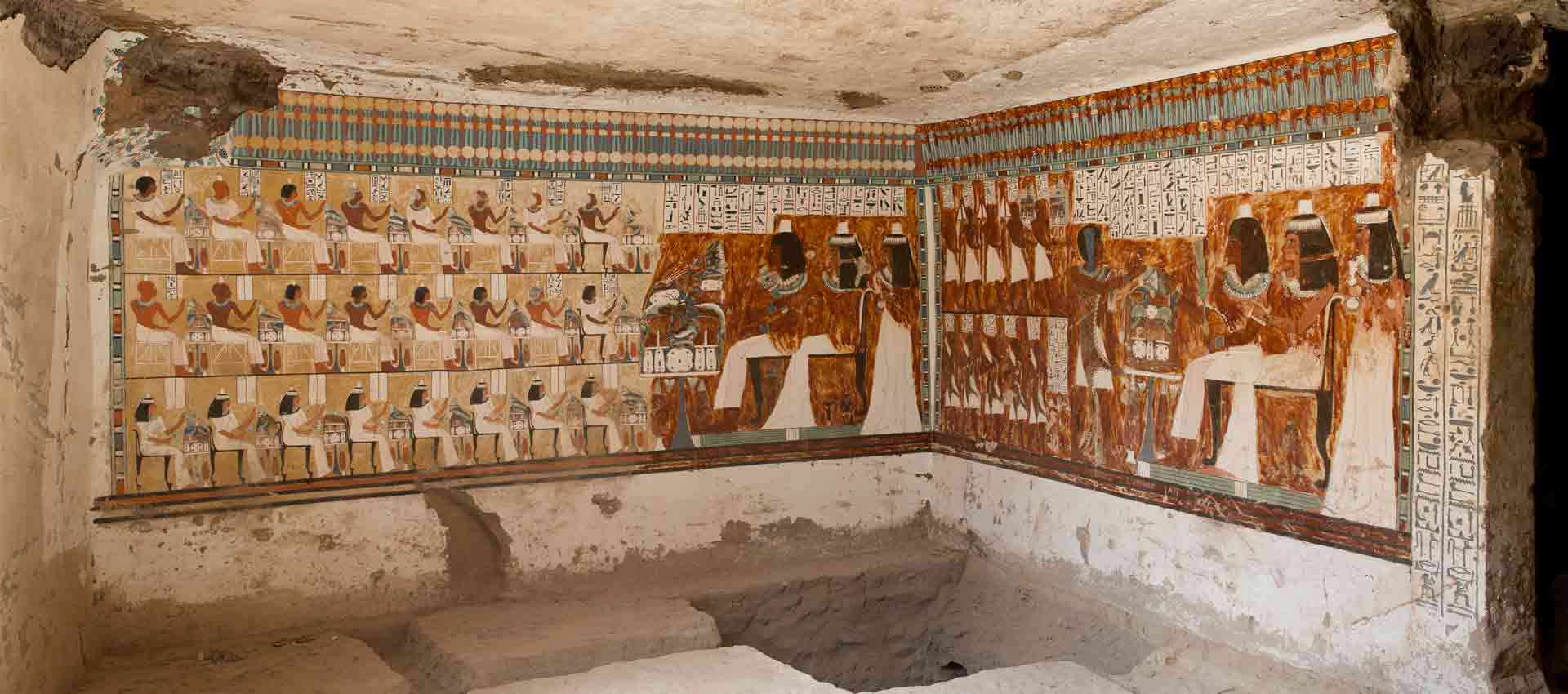

The Heliophon, cat. no. 5286, which was built by Bruno Helberger and Peter Lertes in approximately the year 1940, is a good example of the large range of materials used in early electronic instruments, including wires, tubes, switches, wood, and many other materials. This instrument is a unique specimen and a valuable example of the early history of electronic instruments. Photograph: schnepp renou

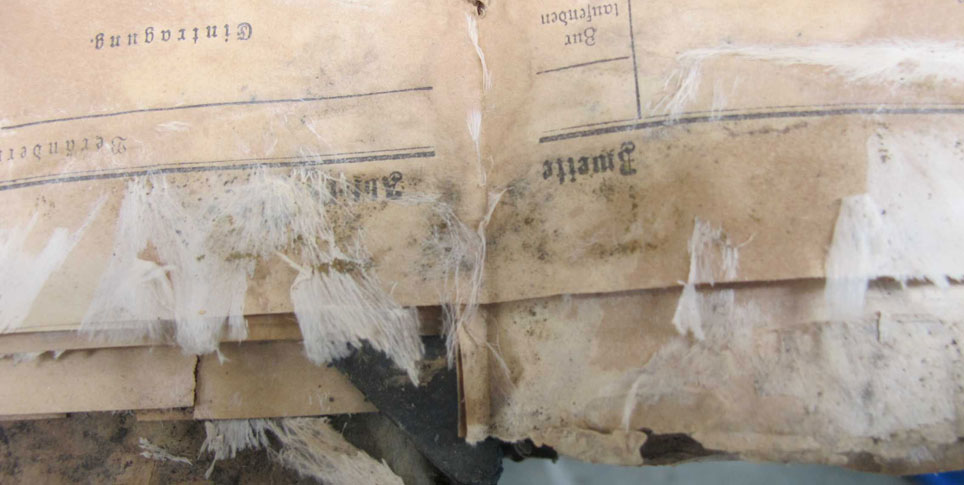

The special challenges of dealing with an instrument collection that includes electronic instruments arise first of all from their characteristic material features. The plastic outer casings and the numerous controls – buttons, toggle switches, knobs, sliders and so on – are just the tip of the iceberg. Experience shows that synthetic materials age quickly. Plasticizers or solvents, for example, start to separate out, which can change the character and composition of the materials significantly in just a few decades. This means that, in the worst case, the surfaces basically crumble, so to speak, when you touch them. If you look at the switches and buttons, the mechanical movements are also a problem, and over the course of decades, just a small amount of lubricant residue can lead to sticking, especially in the case of the rotary knobs and sliders. But even more serious are the problems with conserving the electronics inside these instruments.

Components like microchips, but also simpler parts like resistors and batteries or – as in the first electronic instruments from the 1920s and 1930s – the various forms of vacuum tube, pose nearly insurmountable problems for collections. Some of these electronic components consist of microscopically thin layers of various metals and, over the years, these can react with one another. On a larger scale, the oxidation and corrosion of two metals is also evident at soldering points; this too leads to dysfunctions, of course, and could even cause a fire in extreme cases.

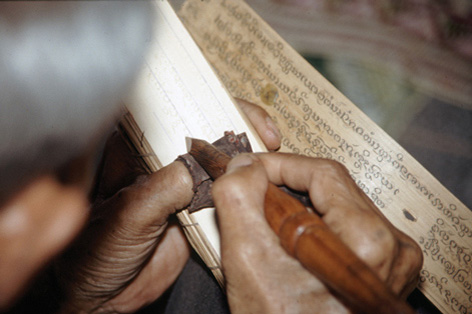

The aging processes sketched out above – in a very brief and incomplete form – take place both on the surface of the object and inside it. But there are additional challenges of a different kind. In the case of non-electronic music instruments in museum collections, such as harpsichords, organs, violins, viols, flutes, or brass instruments, we (the people working with the collections) are sometimes able to draw on traditional methods that have been used for centuries in terms of materials, substances, or tools, and we can use and apply those practices in workshops set up for that purpose.

Electronic instruments, in contrast, have been manufactured in an industrial context and are fitted with highly complex components assembled on large production lines. Not even vacuum tubes can be rebuilt in restoration workshops – to say nothing of microchips. This means that it is impossible to create “replacement parts.” A lot of time and effort has to be spent on locating them instead. And if, instead of modern parts with an equivalent function, you want to obtain only original parts (the sort that were used when the object was first built, or when it was altered, depending on which stage you are aiming to recreate) then the true scale of the problem becomes apparent. And as for vacuum tubes, we currently face the absurd situation that these are themselves highly desirable collectors’ items, sought after mainly by private collectors of historical radio sets or of electronics in general!

Finally, a few brief words about preserving electronic instruments by playing them: to extend the life of the components mentioned above, it is indeed important to use them, because the flow of current seems to slow the aging processes of these electronic components. Hardly any systematic research has been done on this, and in my work, I have taken processes used for testing materials in the field of medical device research as a reference. The difficulty with this, however, is that it presupposes that you have a functional instrument – something that cannot be taken for granted. And if you wanted to return it to a functional state, you would first have to do a thorough evaluation and comprehensive servicing – quite apart from the issue of documentation. Since the restoration of such complex technologies and devices is a subject that has only recently begun to be taught, and since the requisite infrastructure is only rarely in place, dealing with electronic instruments in the context of a museum collection poses an enormous, complex challenge.

How did people react to the emergence of electronic sound generators and electronic music?

There was naturally an extremely wide range of reactions. What is especially interesting, if you review the early history of this, are the reasons that were given and the way in which the positive and negative criticisms were distributed among the various “groups,” such as composers, musicians, researchers, laypeople (in terms of music or electronics) et cetera.

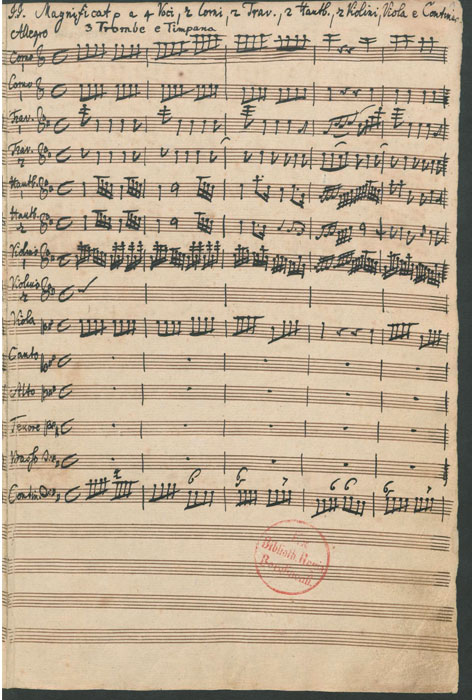

One early example is the telharmonium, also known as the dynamophone, created by Thaddeus Cahill of the United States. This was developed around 1897, and it had rotating, gear-like wheels that generated sound. Cahill’s own perspective on the instrument naturally derived from his interest in successfully marketing his creation; he saw it as a way to provide anybody and everybody with music down the telephone line – for a small fee. A variety of critics did respond very positively to the music produced by his instrument. It is often asserted that composer Ferruccio Busoni admired this instrument, which is somewhat of an over-simplification. He did so from a very specific perspective. His idea of producing smaller intervals as semi-tone steps – namely as thirds and sixths of tones – could, he thought, be achieved not just vocally and with string instruments, but also with the dynamophone. The music that was played on the dynamophone was mostly drawn from the repertoire of Classical and Romantic composers; Cahill also had to think in commercial terms, of course. This example also shows that electronic music identifiable as such only emerged some years after the development of corresponding instruments.

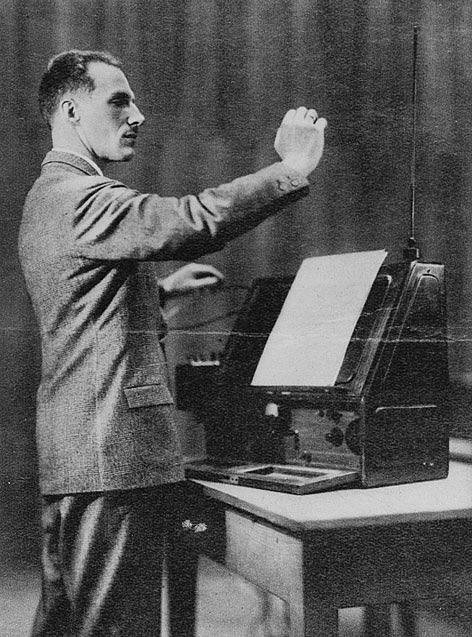

Another stage in the development of electronic music was marked by the International Music Exhibition in Frankfurt am Main, in 1927. At the time, it was already clear that public broadcasting would soon be the next big area of development, and this was reflected in more nuanced responses to instrument designs that used the new technology. At this major exhibition, a Russian called Lev Thermen introduced his instrument to the general public. It was called the “termenvox” or “aetherphone” and it was not the music so much as the unusual manner of playing the instrument that elicited positive – and sometimes downright exuberant – responses. The player controls the pitch and volume by moving both hands within electromagnetic fields, without touching the instrument itself. Extraordinary means of operation or playing were often perceived as a positive feature of newly developed electronic instruments. On the other hand, the critical responses to the termenvox tend to focus on its monotonous tonal range and limited musical potential. Lev Thermen himself played mostly a Classical-Romantic repertoire on his instrument, which is today known as the theremin. His performances triggered a flurry of tinkering and development throughout the early 1930s among composers, amateur inventors, and instrument designers, who were highly receptive to this new trend of generating sounds. This in turn led to ever better and more complex audio outputs. The public, including those parts of the public with professional training, naturally included a few critics who felt, for instance, that these electronic instruments produced a lifeless, mechanical, or technical sound. But many listeners responded quite favorably to the new instruments and their potential.

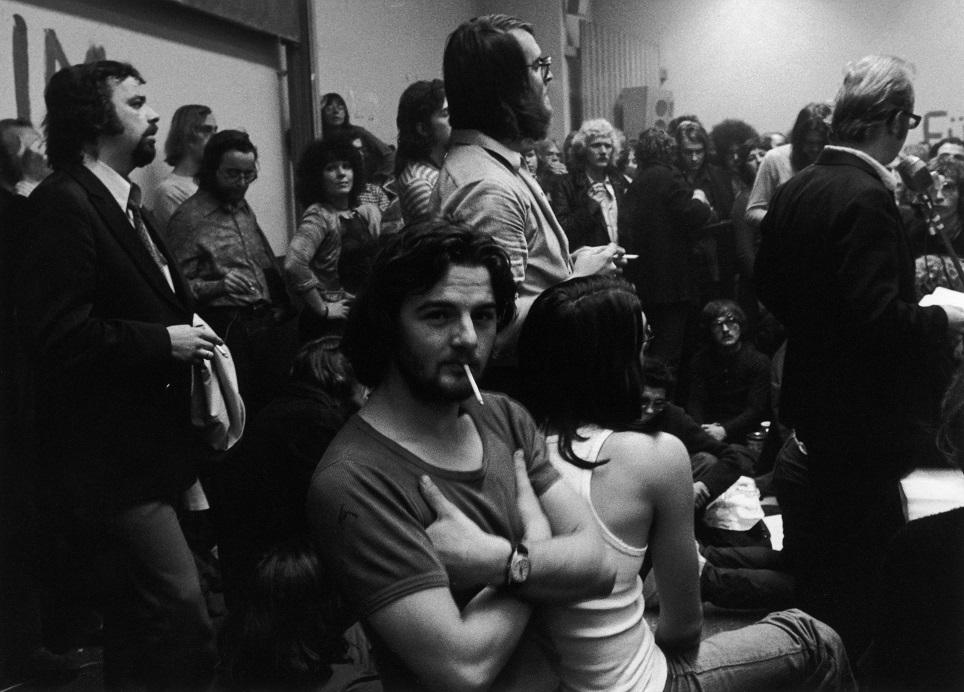

It was not until after the Second World War that “New Music” of an electronic kind was composed in Germany: in the electronic music studio of what was then Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk (NWDR; Northwest German Broadcasting) in Cologne, a group of experts working under Herbert Eimert, Robert Beyer and Werner Meyer-Eppler developed a new and radical type of music, advocating the use of recording tape to generate and transmit sound. Initially, this music met with widespread rejection on the part of “normal” listeners. Not just the sounds, but also the musical syntax posed major challenges to both listeners and artists, and it took several years for this genre to gain first a foothold and then a permanent place in the canon of New Music. Nowadays, no one would deny the significance of electronic music in the musical history of the twentieth century.

Which is more valuable: a violin associated with Beethoven or a guitar that was owned by Jimi Hendrix?

We often get questions like this, especially when we are telling visitors about the Stradivarius violin in our collection. The answer is actually quite simple: what do you mean by “value”? Simply the amount of money? The emotional value, which is something highly subjective? Museums and collections are basically engaged in a permanent discussion of the concept of “value.” The value of an object can be defined in a great variety of ways, depending on the perspective, the focus of a collection, or the task at hand. For the Musikinstrumenten-Museum (Museum of Musical Instruments), the string instruments associated with Beethoven, which are on permanent loan to the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn, are definitely some of the most valuable instruments that we have.

Since we are not explicitly focused on collecting items related to the history of pop music, the Jimi Hendrix guitar (he preferred a Fender Stratocaster), would not have the same value to us. But for collections and museums dedicated to pop culture, it would probably be the other way around. How much these instruments would actually fetch at auction depends on what collectors would be willing to pay for them, and that is a very subjective affair.

But when collections and museums discuss “value,” it is largely without regard to pecuniary factors. For example, famous prior owners could add to the value of an object in a collection, as well as enhancing its identity. As it happens, the names Beethoven and Hendrix both satisfy that criterion, but for very different target groups. Another factor is the importance of an object in relation to a certain cultural movement or trend. Something like a musical instrument can also be viewed in the context of multiple, overlapping lines of development, such as changes in music and musical practice, and (associated) changes in the construction of musical instruments, as well as cultural exchange between various regional and national traditions of music and instrument design. So the concept of “value” has many different dimensions, and any attribution of value is an expression of the particular perspective from which the object is being viewed.