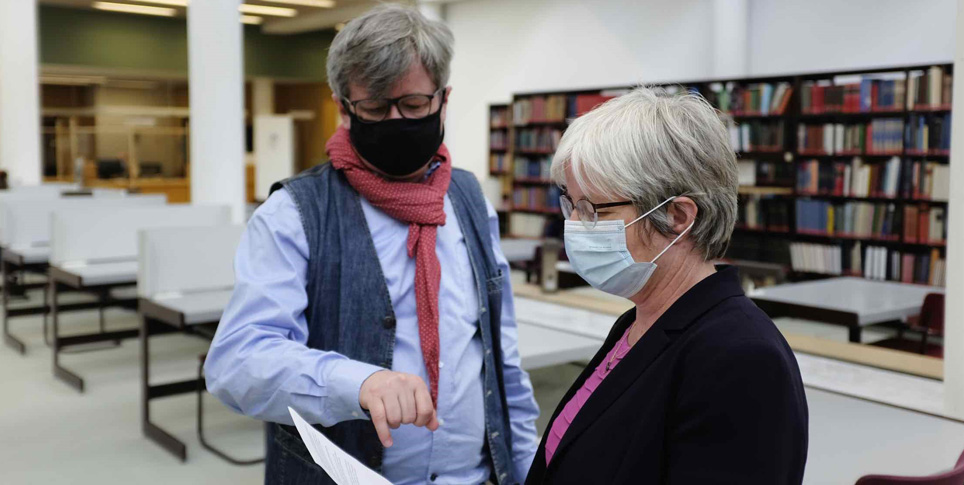

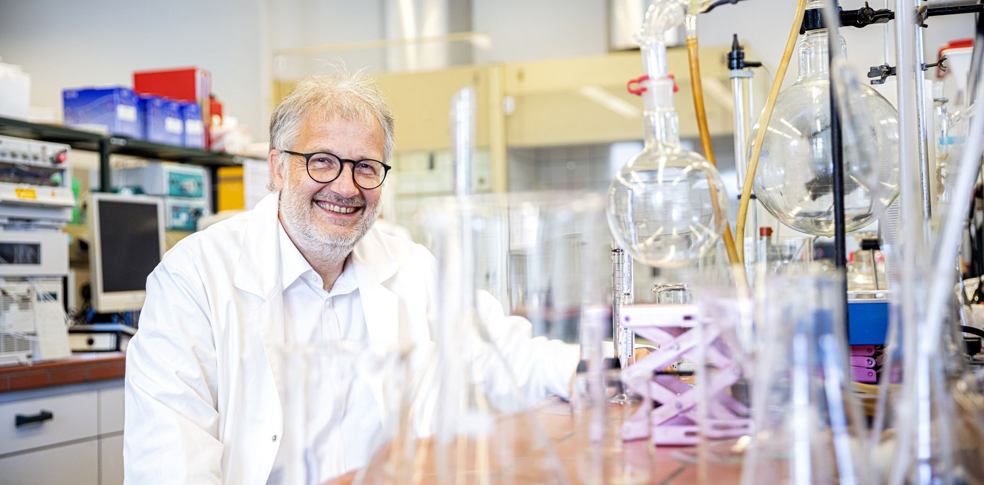

Clemens Neudecker works at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, where he is responsible for research projects on methods of data analysis that use computer vision, natural language processing and artificial intelligence (machine learning). In addition to research into methods for automatically acquiring and analyzing information from digital content, his interests include newspaper digitization and the digital humanities. In the interview, he estimates the chances that AI might soon take his own job.

What are the difficulties faced by automatic text recognition as library holdings are digitized?

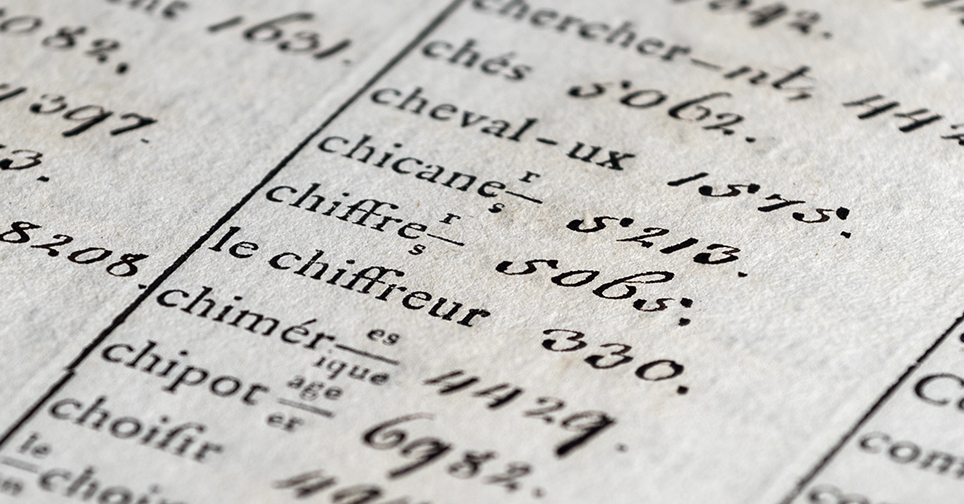

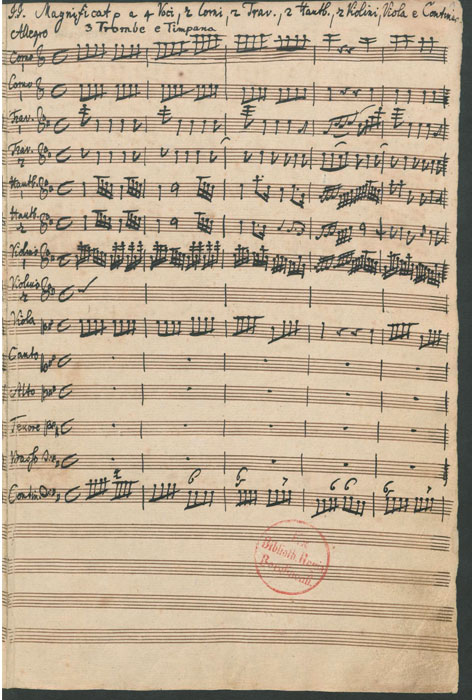

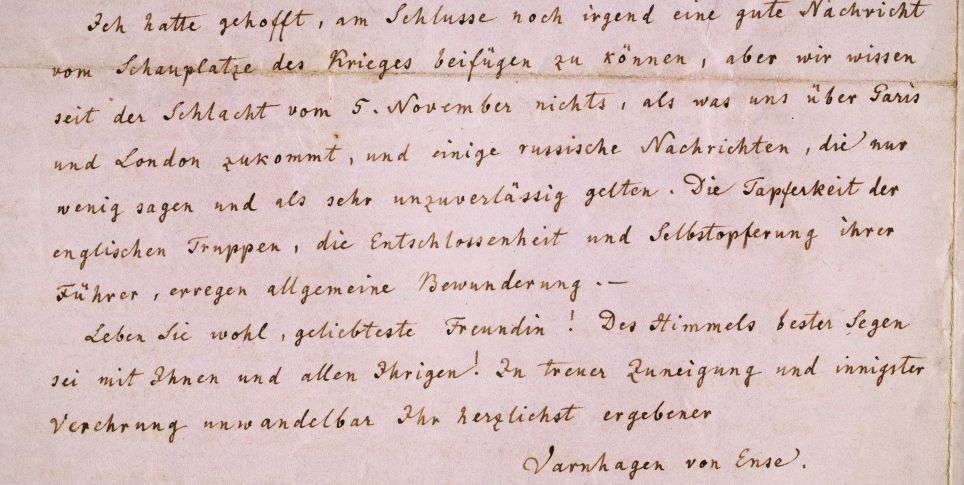

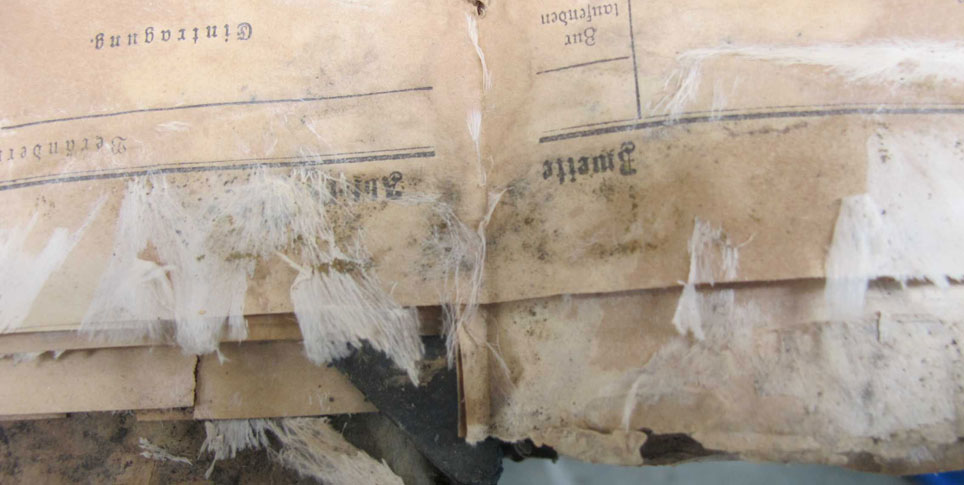

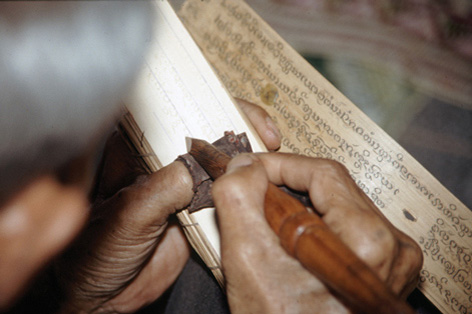

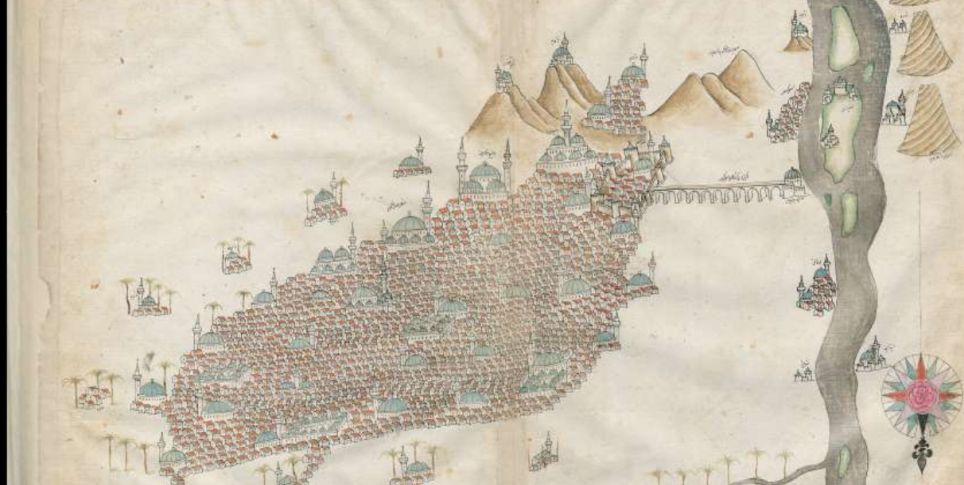

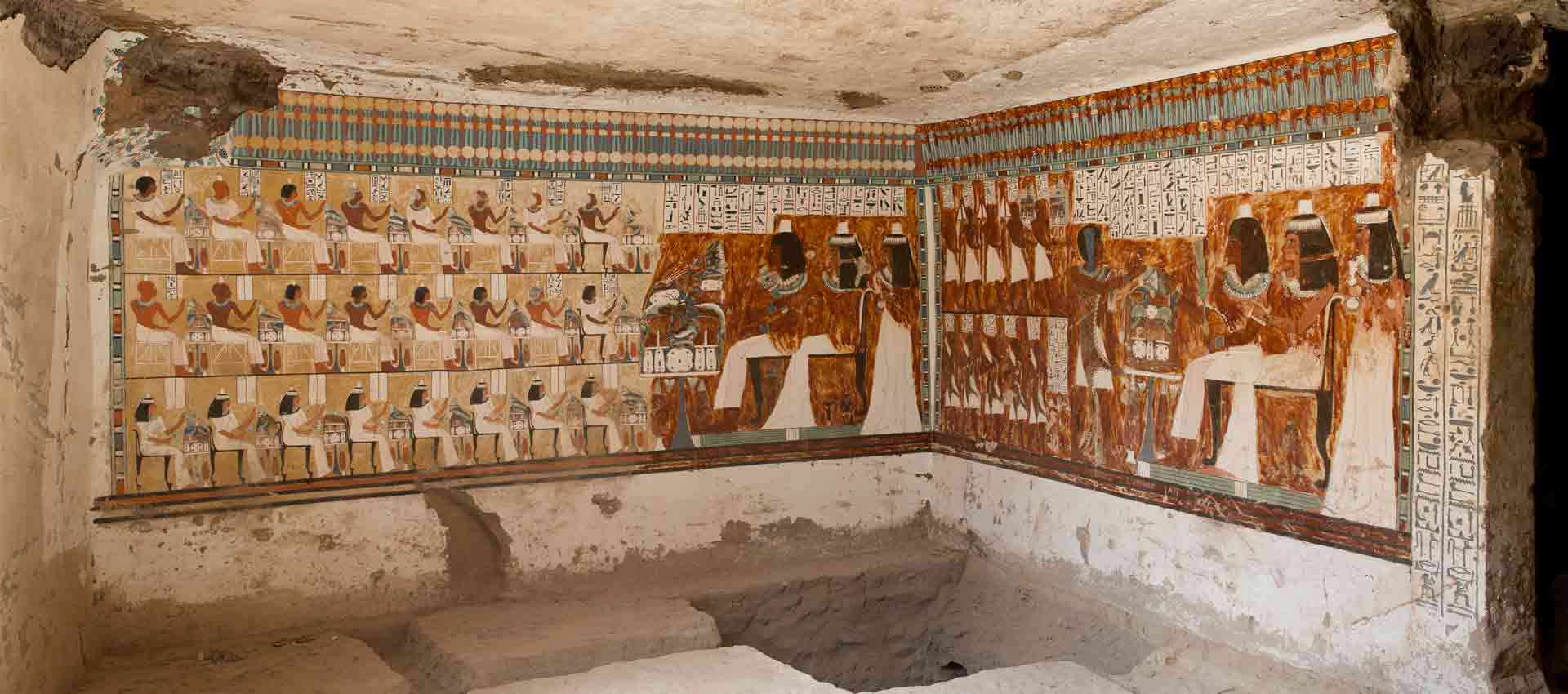

As a result of technological progress in recent years, automatic text recognition (also known as optical character recognition, or OCR), has overcome many well-known problems. Now, for example, it is possible to recognize Fraktur typescripts and even handwriting almost perfectly. But there are still plenty of challenges for text recognition. They result from the four-hundred-year-plus history of printing and the variety of textual material held in libraries and archives, and these challenges will require further research projects and more development.

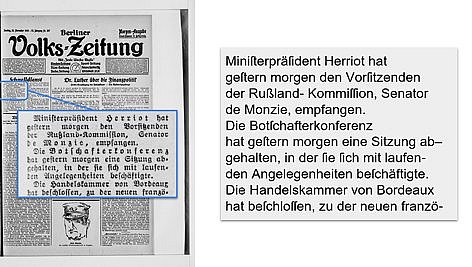

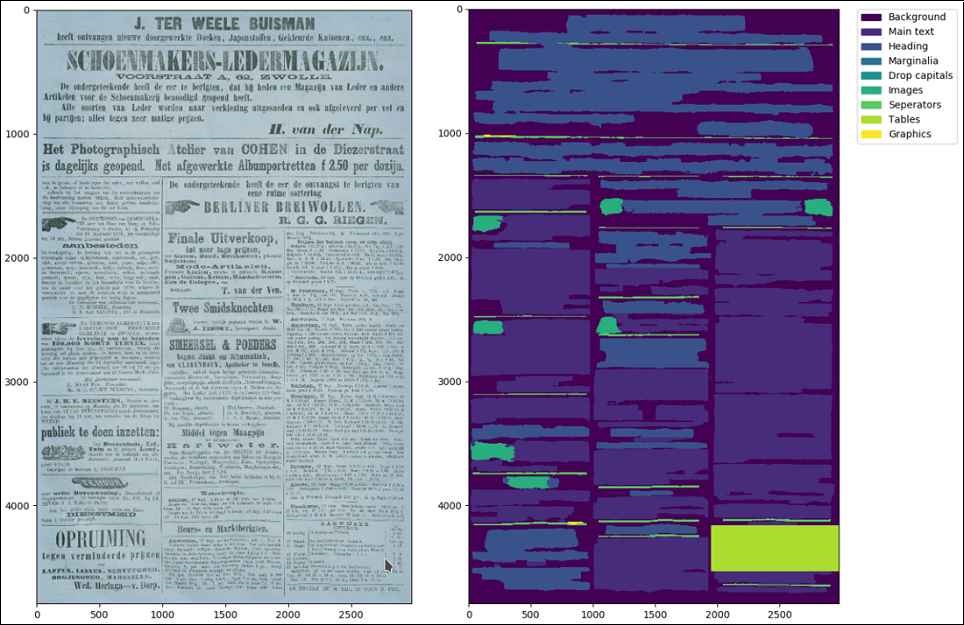

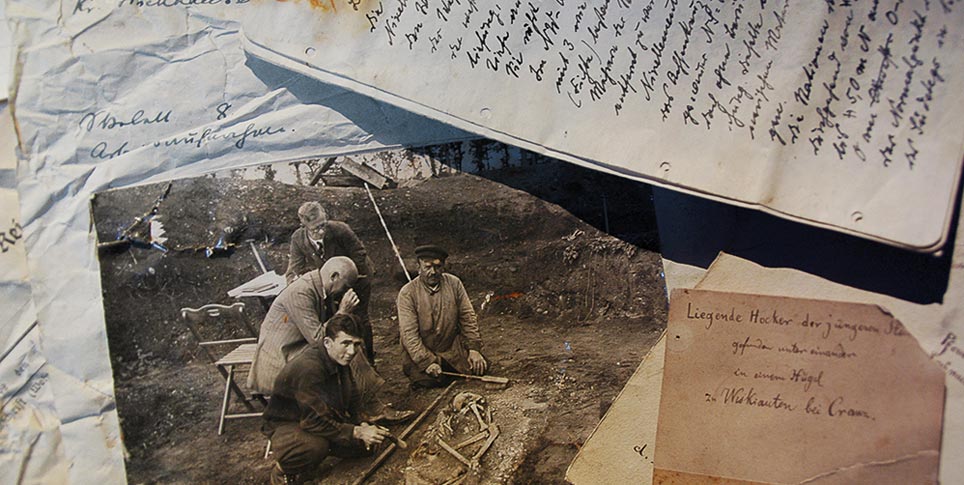

The biggest difficulty is analyzing the layout (or segmentation) of a document. The challenge, in other words, is recognizing and splitting up the different areas on a page, such as paragraphs, headlines, footnotes, tables, illustrations, et cetera. Another difficulty is scalable quality assurance. To assess quality, researchers compare the result of the OCR with the “ground truth,” which is a 100-percent accurate transcription. But when you are dealing with millions of pages, that is not feasible, so different methods and metrics have to be developed for that. We are currently working on all of these issues in the DFG project OCR-D.

What is the most exciting research project that you are working on right now?

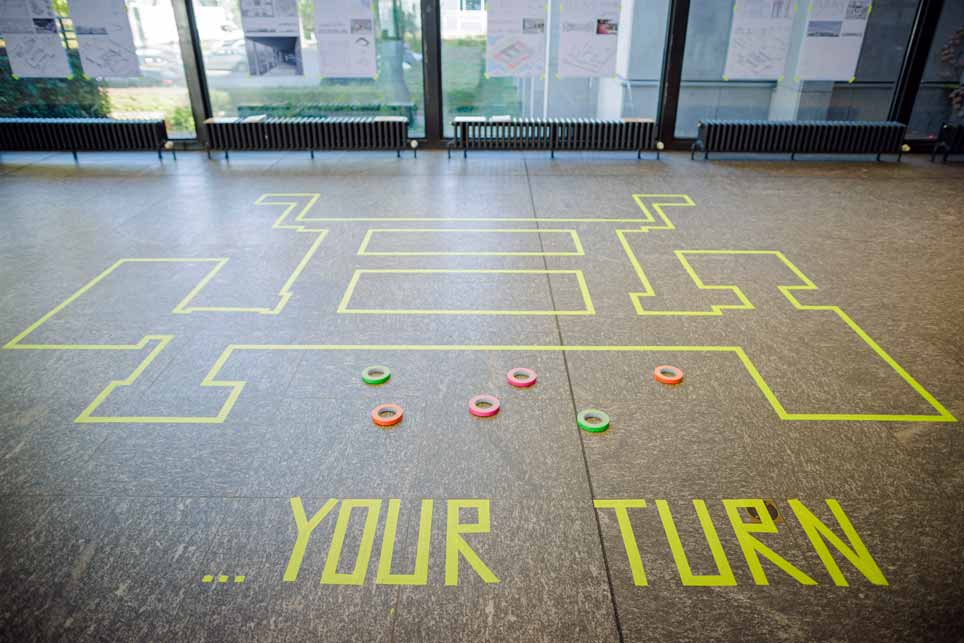

The most exciting research project for me right now is the three-year project „Mensch.Maschine.Kultur“. This has been underway since mid-2022, and it involves taking research projects like Qurator and building on them, expanding them, and – equally necessary for such rapidly evolving fields as AI – bringing them up to date, because a lot has been done here in the last three years. Another aim of this particular project is to take the prototypes that have been developed in prior research efforts and turn them into concrete products and services for the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library) in cooperation with our departments as well as clients from the academic and research communities, such as those working in the area of digital humanities.

One aspect of this project that I am quite excited about is that one of its four sub-projects has been devoted to the important question of how cultural institutions like libraries, museums and archives, which have large quantities of data as a result of digitization, can use this data to improve the AI. And more specifically, it is looking at how they can do so in a way which addresses the potential ethical, social and legal problems of data and AI transparently and with input from the research community, which is a dimension often neglected by commercial AI projects.

Will AI take over your own job at some point?

Sometimes I would certainly like it to, but I don’t think that will happen in the near future or even the distant future, even in the case of those tasks at the library that we’re now trying to automate at least partially. At the end of the day, we have to bear in mind that “AI,” as the term is used outside of computer science, is often a nebulous and very problematic concept. We ourselves prefer to use the term “machine learning.”

That better expresses the fact that we are not developing an intelligence in the sense of something comparable to a human being. Instead, we are trying to teach a machine to do something automatically by showing it many examples – we are trying to “train” the machine to accomplish a very specific task. And for that, there is a greater need than ever for human experts who can, yes, teach the machine something, but also correct it time and again when it makes mistakes.