In the Neue Nationalgalerie's second refurbishment phase, the building fabric and interior fittings of this architectural icon are being comprehensively repaired and renewed.

January 2018 saw the beginning of a further phase of refurbishment work on the Neue Nationalgalerie. In the first phase, the main aim had been to strip the building down its skeleton and to secure, restore, and store the 35,000 or so original components. In the next step, the experts from David Chipperfield Architects concentrated on renovating and upgrading the building fabric, installing up-to-date building services, and beginning the refurbishment of the interior.

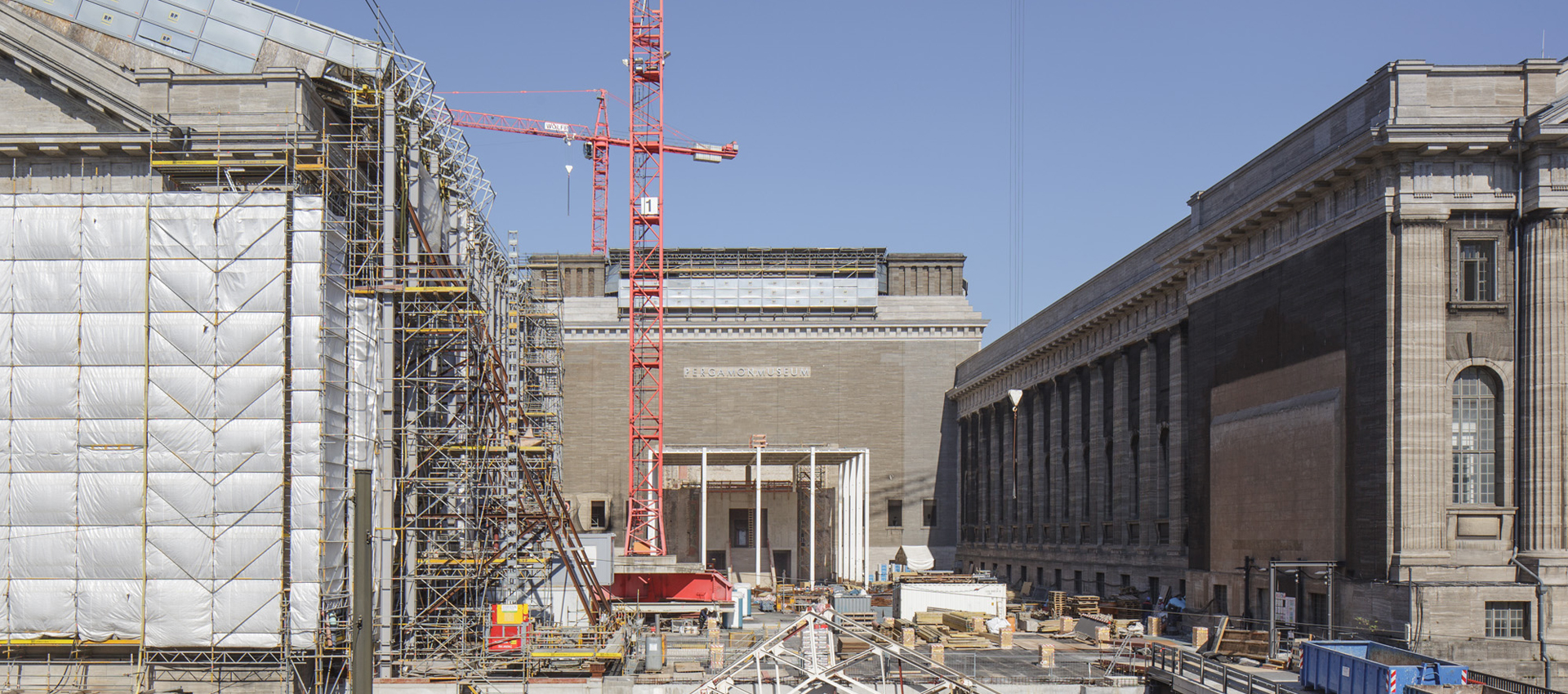

View from the roof into the excavation pit for the depot extension under the terrace facing Potsdamer Strasse. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / schmedding.vonmarlin.

New Concrete

In the winter of 2017–18, the Neue Nationalgalerie was dismantled down to the structural shell – almost back to the state that it had been in at the topping-out ceremony fifty years before. Then began the laborious process of repairing the reinforced concrete walls and ceilings. The building's lower floor level was dotted with red markers to indicate damaged areas, which were of the usual kind for material of the quality used in the 1960s.

Because the concrete surfaces in the Neue Nationalgalerie were concealed behind granite slabs, exhibition walls, or the panels of the module ceiling for as long as it was in use, a comprehensive picture of the deterioration could only be obtained after these had been removed. Over the decades, the materials had suffered considerable damage due to weathering and defects dating from the time of construction. In the course of refurbishment, repairs were made to cracks and areas of spalled concrete as well as rusting reinforcement that had thus been exposed. This meant chiseling concrete off the outer walls to a depth of several centimeters, laying new steel mesh and applying a fresh covering of concrete.

Inside the building, repairs were generally more localized, especially on the modular ceiling. At the lower floor level, cracks, drill holes, and voids were discovered in the concrete above the steel panel ceiling; the cracks were filled by injecting a strengthening emulsion.

Global Glass Procurement

In addition to repairing the concrete, work also began on renewing the building's characteristic steel-and-glass facade, which had been exposed to great stress over the years owing to fluctuations in the local climate. The 56 panes of glass in the upper sections of the facade are each 5.40 meters high and 3.40 meters wide – so replacing them completely was a mammoth task. This step was nonetheless necessary because panes of glass in the Neue Nationalgalerie have been cracking ever more frequently since the mid-1970s.

"There are several causes," says project manager Daniel Wendler from David Chipperfield Architects: "corrosion along the glazing beads, structurally under-dimensioned upper panes, and considerable deformation of the steel structure of the facade due to thermal expansion and wind loads."

The resulting cracks and broken panes, combined with the fact that the facade of the upper hall only had single glazing, meant that safety could only be ensured to a limited extent, especially in recent years.

In order to achieve the proportions that he wanted in the glass facade, the building's designer, architect Mies van der Rohe, went to the limit of what glass production processes were capable at the time. In the Libbey-Owens process, a sheet of glass is drawn into the required shape over polished steel rollers, allowing panes of widths up to 360 cm to be produced.

At the time that the gallery was being built, the last production facilities worldwide still using this drawing process were being retooled to use the float glass process, which is qualitatively better and more economical. This method, in which molten glass is floated on a bed of liquid tin in order to achieve perfect surfaces, works with a standardized pane width of 321 cm.

In 2018, a worldwide search turned up only one glass manufacturer that could produce panes of float glass of the width needed for the refurbishment. The basic glass was produced south of Beijing and then processed by a glass finishing company with larger than usual technical facilities, based in the same city. It was a huge effort, but it was worth it: the new panes come close to the originals in the appearance and color of the glass while offering greater safety and better resistance to breakage.

A New Part of the Building

Besides the refurbishment, a completely new part of the building was created during the second construction phase. The Neue Nationalgalerie now has a new, state-of-the-art storage area and technical room under the terrace facing Potsdamer Strasse. The floor area at basement level has been extended by 900 square meters behind the flight of steps up from the street, unnoticeable for visitors to the museum.

Relocating the 600 square meter depot outside the building’s original footprint meant that the former storage areas could be converted to accommodate the cloakroom and the bookstore. The new layout of rooms has significant logistical advantages for the delivery of works of art and makes it possible for visitors to circulate around the exhibition space in the way that Mies intended once more.

In addition to the comprehensive refurbishment of the building fabric, the second phase of work included the modernization or renewal of building services and interior fittings. It was a constant challenge for the architects and specialists to strike a balance between the respective requirements of historic building conservation on the one hand and modern construction standards on the other.

Renewal of the Air Conditioning

A stable interior climate is essential to the working of any museum today: sudden drops in temperature are as dangerous to a painting's sensitive layers of paint as excessive moisture is to the wood or paper support to which it has been applied. In the meantime, very strict climatic parameters have become established internationally, and these form a binding part of the contracts for lending objects for exhibitions. Today's air conditioning systems must therefore guarantee a specified interior climate, free of fluctuations, as well as meeting standards for energy efficiency and environmental sustainability.

In the case of the Neue Nationalgalerie, the specialists had an especially difficult task to incorporate the requisite technical improvements while respecting the interests of historic building conservation. Here the building's biggest headaches were caused by its iconic design element – the fully glazed exhibition hall. This has a volume of 25,000 cubic meters, enclosed by a steel-and-glass facade with a height of 8.40 meters. Underfloor heating was originally planned for the hall, and this was renewed as part of the refurbishment. The ventilation system, with supply and exhaust air ducts installed in the pillars and the ceiling, was given a technical upgrade with new components. Here, one of the biggest problems in need of a solution was the formation of condensation on the large panes of glass.

Mies van der Rohe had been well aware of this phenomenon, but he had accepted it as a trade-off for the beauty of his architecture. The refurbishment offered an opportunity to counter it by installing modern facade ventilation technology. A specially developed system now blows air all the way up the eight-plus meters of the glazing and reduces the formation of condensation to a large extent.

Modernized Lighting

Another technical challenge concerned the interior lighting. In his presentation for the new building of the Neue Nationalgalerie, Mies made proposals for homogeneous lighting that would not create lighter and darker zones on the exhibition walls. This was to be achieved by using wallwashers – lamps built into the ceiling parallel to the wall.

As part of the basic overhaul, the 2,400 or so existing built-in lights were carefully converted to LED technology and the light fixtures were refurbished. This has allowed the original lighting scheme and layout to be retained along with the visible original parts of the fixtures while satisfying modern technical standards and exhibition requirements. In addition, a new control system will enable the brightness of each luminaire to be adjusted separately, so that the levels of interior lighting can be adapted to changing daylight intensity and to the different sensitivities of various works of art.

Ceilings, Floors, and Walls: the Interior Fixtures#

The interior renovation began with the removal and replacement of basic elements such as the dividing walls, ceiling cladding, and floor coverings.

Mies had used a modular ceiling with panels that could be rearranged easily in response to changes in the room layout. It turned out that they were not all that easy to remove, as the panels were of engineered wood, screwed to a wooden supporting grid and then plastered over. This outmoded construction was also fairly combustible and thus no longer met current fire safety requirements. "The comprehensive refurbishment aimed to improve the structure in terms of fire safety and functionality while keeping the original appearance of the ceiling," explains Michael Freytag from David Chipperfield Architects.

New panels made of metal and fire-proof vermiculite have now been installed, which really can be demounted easily and rearranged as desired. Like the panels of the original ceiling, they have openings for technical fittings.

The floor covering has also been completely renewed. The modular suspended ceiling was originally complemented by a bouclé carpet made of pure new wool with a salt and pepper pattern. Laid over the entire floor area, it was exposed to heavy wear in many areas of the museum and was completely replaced several times over the decades. Without any surviving sample from the time of the building's construction, the carpet's exact appearance had to be reconstructed from photos and personal recollections. The new carpet, consisting of a wool-polyester blend, was commissioned from the company that had manufactured the original in 1968.

Cloakroom and Museum Shop

The last phases of the interior refit concerned furniture and small fixtures, the cloakroom, and the museum shop.

The capacity of the original cloakroom soon became inadequate for the needs of a modern museum. The number of visitors increased so much over the years that space for additional coat racks had to be found. With no suitable room available, the new cloakroom was inserted along the northern side of the museum, but this meant that it interrupted the circulation of visitors around the exhibition space envisaged by Mies van der Rohe, as well as blocking an escape route.

Now the extension under the terrace towards Potsdamer Strasse has freed up space elsewhere in the building, allowing David Chipperfield Architects to install the cloakroom in a former storage room for paintings. This larger space accommodates additional coat racks, a group cloakroom, and lockers, as well as a point for borrowing buggies/strollers and wheelchairs. A new elevator at the entrance to the cloakroom area offers disabled access between this and the visitor toilets below and the exhibition hall above.

The museum shop also had to be relocated. In his design drawings for the museum, Mies had provided for a sales table in the "refreshment room," the room that was used as a vending machine café for visitors in the first few years after the museum opened. As the range of items on sale increased, more space was needed, and in 1979 glass partitions were installed to enclose an area between the café and the stairs, which was occupied by an independently operating bookstore.

As with the cloakroom, David Chipperfield Architects have used the former sculpture storage room for the new museum shop, which therefore remains opposite the café. Now, however, it occupies a larger area, which can be leased to an external operator as a self-contained unit.

With these and other laborious and challenging stages of refurbishment now complete, David Chipperfield Architects and the many different specialists involved can take stock of their achievement: to repair and modernize one of Berlin's great architectural icons while simultaneously restoring the appeal and grandeur of Mies van der Rohe's original vision. This summer the building will finally reopen after five years of painstaking work, fully equipped to serve the needs of a modern, world-class museum for the next fifty years.