Renovating the Neue Nationalgalerie according to protected monument specifications is a gigantic project. Starting in 2015, Mies van der Rohe’s architectural icon was gutted and all the original components, numbering in the tens of thousands from original light switches to the cloakrooms, have been removed, restored, and placed in storage.

According to Martin Reichert, out of respect for Mies van der Rohe’s legacy almost no changes worth mentioning were made to the Neue Nationalgalerie in almost 50 years. Reichert, an architect and partner at Chipperfield Architects, said in 2015 that the intensive exhibition schedule that has drawn millions of visitors since opening in 1968 left its mark on the house at Kulturforum. At that time, it was obvious that the renovation and careful modernization of the famous monument was more than overdue.

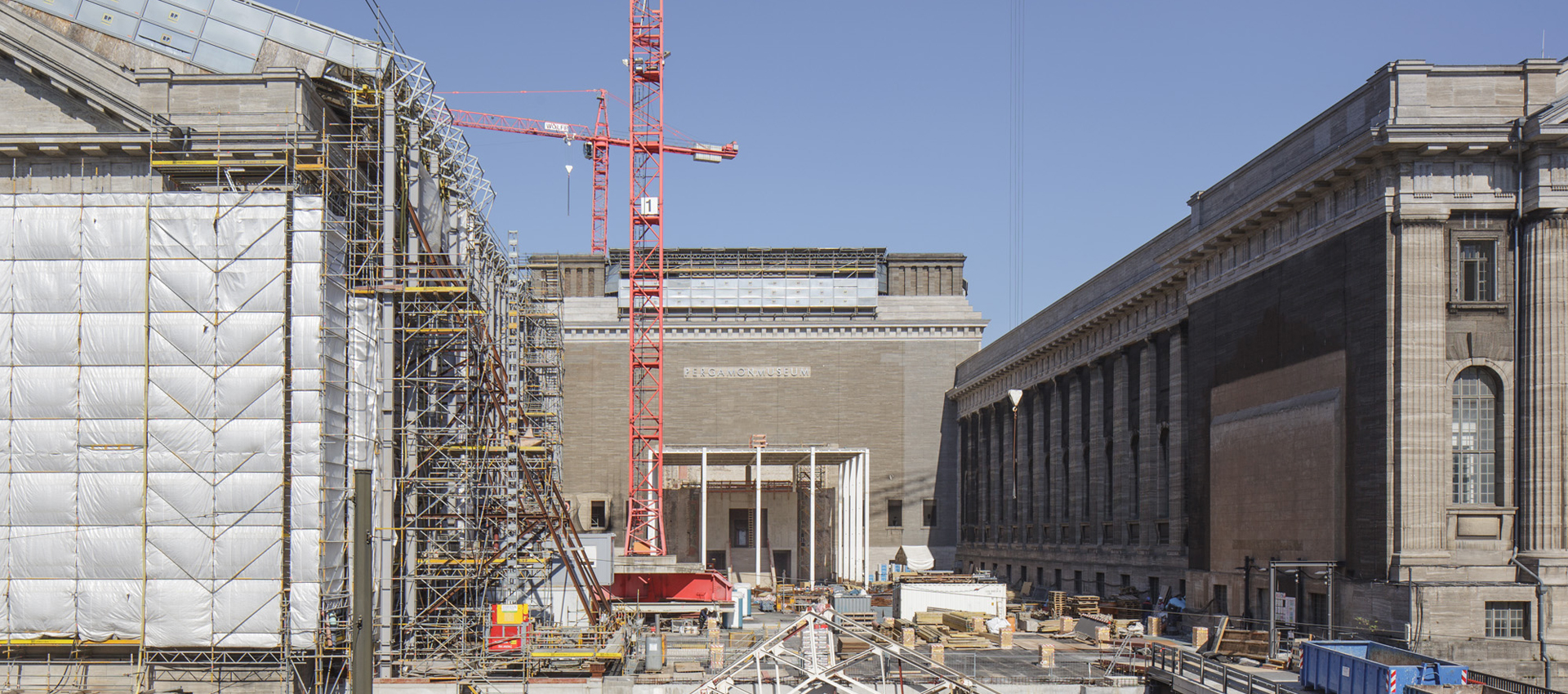

The Neue Nationalgalerie before the renovations began, late 2015 © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Juliane Eirich

According to Martin Reichert, out of respect for Mies van der Rohe’s legacy almost no changes worth mentioning were made to the Neue Nationalgalerie in almost 50 years. Reichert, an architect and partner at Chipperfield Architects, said in 2015 that the intensive exhibition schedule that has drawn millions of visitors since opening in 1968 left its mark on the house at Kulturforum. At that time, it was obvious that the renovation and careful modernization of the famous monument was more than overdue.

David Chipperfield’s firm is an optimal partner for this undertaking since Chipperfield and his team have already acquired experience with the modernization of listed buildings in numerous other renovation projects, including the Neues Museum (opened 2009). “New complements old, carefully but also self-confidently,” said Chipperfield to summarize his credo.

reserving the original solution plays an especially important role with Mies van der Rohe. For example, the precise contrast between cool glass-and-steel architecture with warm wood tones and green marble was conceived with great attention to detail. It is what defines the quality of van der Rohe’s architecture.

Clearing out and taking down

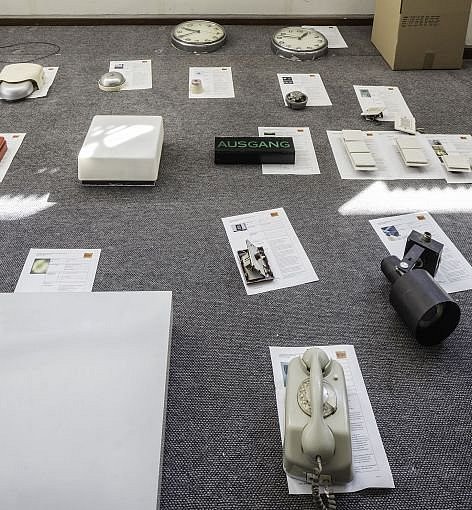

From the beginning, everyone agreed that Mies van der Rohe’s Modern age icon should retain as much of its original form as possible, even if this meant additional costs and effort. The materials and interiors would not be replaced, but instead restored – this applies to the granite plates on the terrace and in the large hall, the wood paneling, and historic furniture, like the famous Barcelona chairs. “Keeping the original aesthetics and materials is very important in an iconic house like this one,” Museum Director Joachim Jäger explained at the beginning of the renovation. Commitment to the original form involved an enormous logistical task. Over 10,000 objects had to be dismantled, documented, and stored in a central location before being given to specialized workshops for restoration. Each object will be returned to its original location with the help of scrupulously kept repositioning plans. “We are breaking the Mies van der Rohe temple down to its individual parts and putting it back together again,” said Reichert.

A lot has happened since the first planning and long, drawn out concept phase before the renovation began. The first step was clearing out and dismantling the museum by late 2016 and turning the building into a shell. The dismantling sequence had to be determined, storage space had to be scouted within the entire city, and an inventory system with a database had to be created. In the summer of 2016 on the lower floor of the building, countless pieces of carefully labeled, original van der Rohe furniture, house telephones, bell buttons, alarms, light switches, electrical outlets, and signs waited to be taken away.

Dealing with materials according to monument specifications

Preserving the original materials and furnishings from the beginning of the Neue Nationalgalerie also meant studying them professionally and planning individual restoration measures. “We need to take the material seriously,” said Reichert about the restoration work back then. There were many challenges, since the materials that the specialists had to deal with ranged from marble paneling from the top floor and wooden surfaces from the cloakrooms to glass panes, coats of paint, and other seemingly minor details such as sinks and curtain rails. Especially the technical systems made restoring to original condition difficult because of the technological advancements in the past 50 years. Facility details that are visible to the public, like outlets and light switches, ventilation grills or light fixtures were brought up to date technically where possible.

To do justice to this huge job the architects and engineers were able to rely on the help of professional building restorers. ProDenkmal, a company specializing in restoring building interior and exterior components and surfaces according to monument specifications, had already worked on a concept for dealing with the wood, stone, and metal components in 2013.

The complexity of some of the problems can be seen in the treatment of the wooden surfaces, for example. Mies van der Rohe used English brown oak for many of his interiors, including that of the Neue Nationalgalerie. But this is not a type of wood; it is normal oak that has been discolored to shades ranging from dark brown to honey by fungal red rot. So the reddish brown color in Mies van der Rohe’s buildings developed naturally and was not produced artificially. But this special color is not particularly light-resistant and so surfaces like those in the cloakroom areas faded over time. Restoring it to an even surface color was a special challenge because the wood was treated with linseed oil when it was installed and staining it would have led to uneven results. A complex process was developed in which shellac and a pigmented glaze were applied in several reversible layers to reach the desired results.

Restoring the wood was only one of ProDenkmal’s challenges. The original steel construction part coating was also exposed after removing many layers of paint using a complicated process. At times, it was restored meticulously by hand.

Mies van der Rohe was the son of a stone mason and his buildings drew attention to the use of natural stone. In the large hall and the surrounding terrace, 14,000 characteristic granite plates had to be mapped, catalogued, dismantled, and stored by stone masons during the renovation work until they could be used again. With the aid of exact mapping to document the location and position of each piece, each plate can be returned to its original location. In the meantime, ProDenkmal’s professional restorers are cleaning and repairing the plates, and replacing broken parts. A stone will only be replaced in the worst case: when it has been completely destroyed.

When the stone plates were removed, it became possible to determine their source, which was unknown until then. Tests showed that they are very likely to have been made from Striegau granite, which is still being quarried near the Lower Silesian town of Striegau (Polish Strzegom).

The stone masons encountered far more valuable stones inside the Neue Nationalgalerie. The supply ducts in the upper hall are paneled with hand-picked plates of green Tinos marble. “Mies wanted to bring the color green into the hall, but not so dominantly that it competed with the pictures on exhibit,” recalled Dirk Lohan during an inspection of the building site in 2017. He is Mies van der Rohe’s grandson and was the project director in the architect’s offices when the museum was first built. “That is why the plates were ground and not polished: they were not supposed to reflect.” In order to add modern building technology to the shafts, one side of the valuable paneling will have to be opened. The other surfaces will be covered during the renovation and only cleaned – the danger of damaging them is too great to remove them all.

Where is the art?

Along with the building renovations, the question of what to do with the artwork while the museum is closed also faced the Neue Nationalgalerie team from the beginning. Comprehensive research was necessary. What security standards would have to be followed and what climatic conditions did the artwork need?

Ultimately, 967 paintings, 459 sculptures, and 24 outdoor sculptures from the Neue Nationalgalerie collection were distributed among the depots of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) on Museumsinsel, in Charlottenburg, and in Hohenschönhausen. Some works were sent to rented facilities in Großbeeren and Oberschöneweide. Preparations for transport took from November 2014 to August 2015; the artwork was packed and transported between July 2015 and December 2015. The Neue Nationalgalerie restorer, Hana Streicher, has been supervising the depots since then. She goes to them regularly to monitor the artworks’ condition and tend to lending the objects in the collection to international recipients, which will continue during the renovation.

Some of the works are also moved around inside the Nationalgalerie (National Gallery). The Neue Gallery was opened in the Hamburger Bahnhof in November 2015; it is a separate area where works from the Neue Nationalgalerie are being exhibited while the museum is closed. “The original idea of the Neue Galerie is older,” explained Nationalgalerie Director Udo Kittelmann shortly before the opening. “We talked about how we could continue to present the works of the Neue Nationalgalerie to our audience, but we did not want to just line up the masterpieces. Instead, we are planning to give the collection new perspectives in new constellations.” Since then, several exciting exhibitions with works from the Neue Nationalgalerie have been held in the Hamburger Bahnhof, including the highly respected show The Black Years about the history of the Nationalgalerie between 1933 and 1945. Rudolf Belling and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner have also been exhibited.

The most recent project, which is currently attracting a great deal of attention, is the exhibition Emil Nolde – A German Legend. The Artist during the Nazi Regime. This helps Berlin’s residents keep the Neue Nationalgalerie in mind during the long renovation period.