Two masks from Colombia were held at the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin for just over 100 years before being returned in June 2023. They are simple-looking wooden objects, but they have a special meaning for the indigenous Kogi people. In the interview below, Manuela Fischer, curator of the South America Collection, explains how they ended up in Berlin.

Who are the Kogi?

Fischer: The Kogi (also called “Kágaba”) are one of the four indigenous communities of the eastern Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountains in northern Colombia, the others being the Ijku, Wiwa and Kankuamo. The approximately 16,000 members of the Kogi tribe live on the steep northern flank of the isolated mountain range. The rivers that discharge into the Caribbean form the entryway to their territory, which rises to an elevation of 5775 meters at its highest point. This indigenous territory is protected. In 2018, the Colombian state issued Decree 1500, which defines the boundaries of the territory as the linea negra (literally “black line”), which coincides in part with the road that surrounds the mountain range and a number of the sacred sites. In recent years, the state and NGOs have tried to expand the territory through land purchases. The farms of the Kogi are scattered across the slopes of the Sierra. The villages are used for gatherings and celebrations. Among the Kogi people, the separation of the sexes takes the form of separate meeting huts for men and women. Likewise, the women and children live together in their own huts, separate from the men.

The Kogi who live at the foot of the mountains maintain relations with the state, NGOs and neighboring farmers, and they produce crops for the international market, including coffee. The Kogi who live at higher elevations often hold a skeptical view of Western medicine and literacy, because they are incompatible with their traditions. The community is understood as a unit, and as taking part in a direct, unmediated relationship with the territory. During their long period of training and associated deprivation, the religious specialists, the mamos, acquire special knowledge. This knowledge allows them to explain illness as a consequence of social offenses, perform rituals to accompany the change of seasons and bring about decisions within the community.

What do these masks mean to the Kogi?

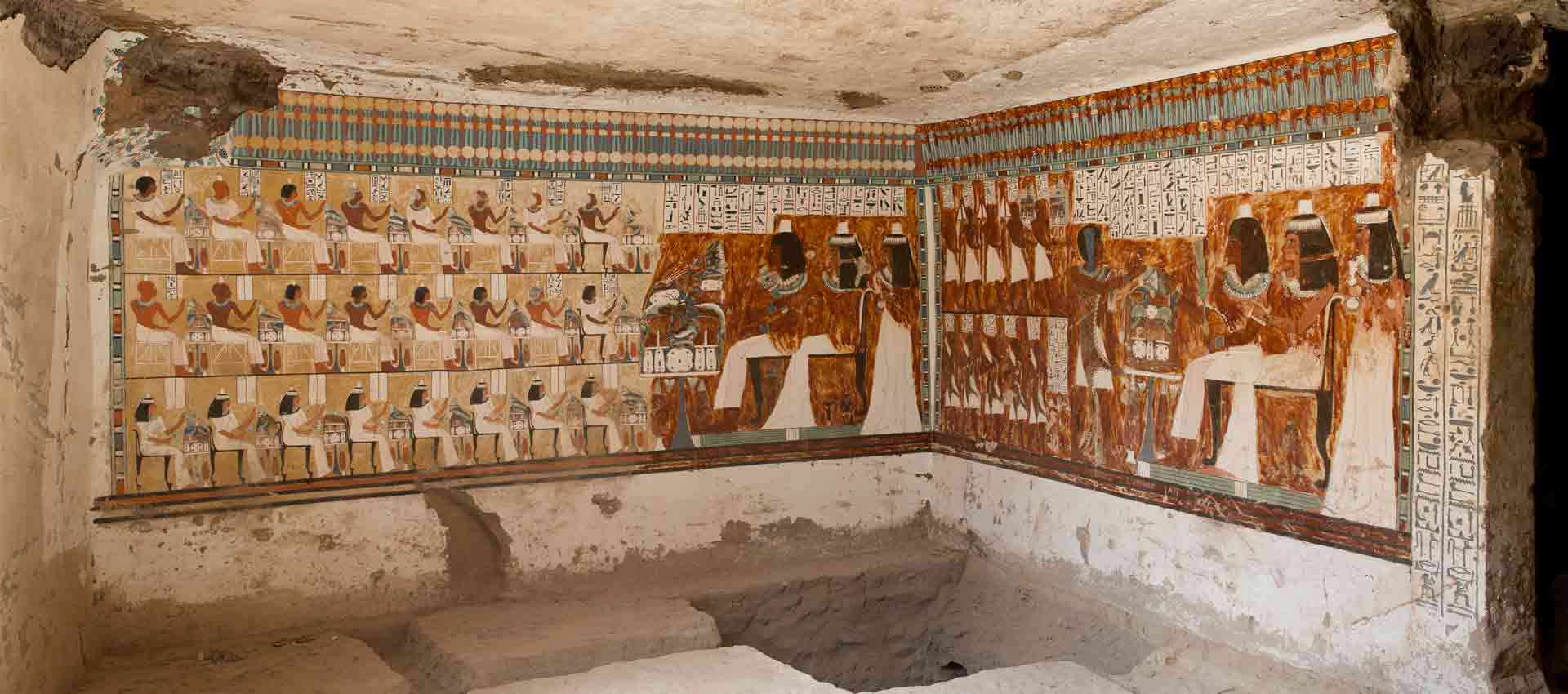

For the Kogi, masks represent mythical ancestors to whom various functions are attributed. During celebrations to mark the change of seasons, and at other occasions, they are used in ritual dances to define time and space. The same is true for the two masks that are now being returned. These are "sun masks”; in other words, they are used to usher in the dry seasons in June and December.

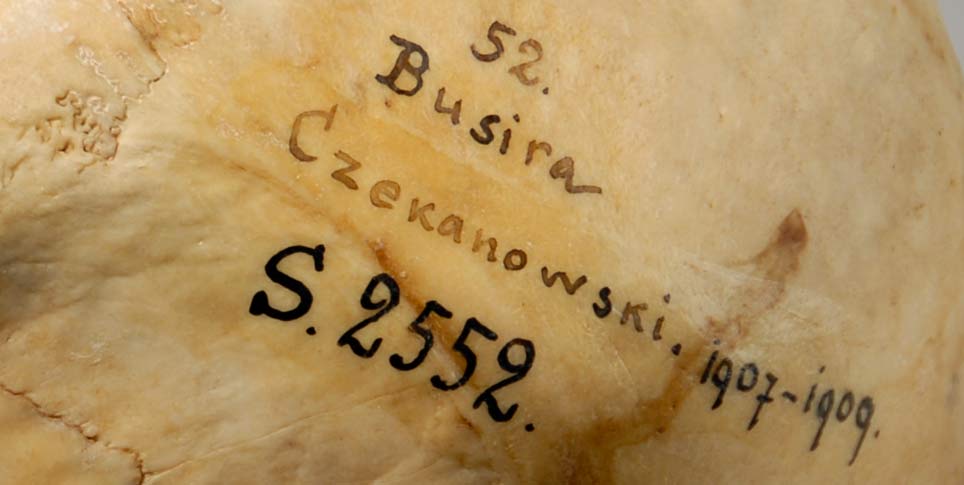

One special feature of these masks is their age. It has been a long time since the Kogi made any masks. All the preserved masks date back to the pre-Columbian era; this has been confirmed by archaeometric analysis of the two masks in the Ethnologisches Museum. The mask with the coca awl, object number V A 62649, was dated to 1470 AD; the mask with the repair – object number V A 62650 – was dated as far back as 1440 AD.

An impressive age for wooden masks. Were they used for centuries?

Yes, we assume they were. The age supports the thesis that paraphernalia used in rituals, including the masks, were made at the founding of the temples, the men's meeting houses, in other words. The repair work on one of the masks is a further indication that a mask cannot simply be replaced with a new one. Instead, they are passed down by the mamos from generation to generation. The list of 39 generations of mamos at Noavaka, the place where the masks are from, is confirmed by the absolute C-14 radiocarbon dating.

It was Konrad Theodor Preuss who brought the masks to Berlin. How did he become interested in the Kogi?

Konrad Theodor Preuss conducted his research expedition to Colombia between 1913 and 1919 in his capacity as curator of the North American collections at the Berlin Royal Museum of Ethnology. With his research focus in the ethnology of religion, Preuss studied the sculptures of San Agustín in southern Colombia to learn what they revealed about the spread of religious ideas and influences from the South American lowlands. To this end, Preuss recorded myths and ritual texts among the Uitoto, Koreguaje and Tama people on the Orteguaza River. He originally intended to stay in Colombia for one year, but his visit was extended to 1919 after World War I broke out, because maritime connections to Germany had been interrupted.

While still in Germany, Preuss had paid a call to the geographer Wilhelm Sievers, who had traveled around the Sierra Nevada from 1884 to 1886 and published an account of his experiences. As a result, Preuss was able to spend several months with the Kogi also. In cooperation with several mamos, he recorded myths and songs in the language of the Kogi and published them with a translation in 1926. In addition, he gathered a small collection of Kogi objects, of which about eighty are still preserved today.

How did Preuss come into possession of the masks?

Preuss acquired the two masks from the heirs of the deceased mamo Fermin Vacuna, "thanks to the favorable opportunity," as he wrote in his book Forschungsreise zu den Kágaba (Research Expedition to the Kágaba) in 1926. Neither the age nor the special significance of the masks was known to him at the time.

It was stated in articles that the Kogi masks are heavily contaminated by pesticides and other substances. Is that true?

As was common practice at museums in many countries, large portions of the collections at the Ethnologisches Museum were treated for decades with pesticides and fungicides to ward off insects and molds. To preserve organic materials such as wood, leather, feathers or fibers, they were sprayed with chemicals that later turned out to be very dangerous. Dichlorobenzene, camphor, arsenic, naphthalene and DDT were used, among other chemicals. Analyses have shown that these substances are present mainly in the dust that has accumulated on the surface of the objects. In preparation for their return, the two masks were therefore cleaned with soft brushes and a vacuum cleaner to remove any dust that might have been contaminated with biocides.

Are there any other Kogi objects at the Ethnologisches Museum?

The phonograph recordings from Colombia are kept in the Phonogram Archive of the Ethnologisches Museum. Of the one hundred wax phonograph cylinders from Colombia, ten were recorded in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Of the photographs that Preuss and his assistant, Telésforo Gutierrez, took among the Kogi, 54 have been preserved at the Världskulturmuseet (Museum of World Culture) in Gothenburg, Sweden. Until the 1930s, there was a lively exchange of objects and other materials among museums, which was a reflection of the universalist aspirations of museums that still existed at the beginning of the twentieth century. In this context, relatively small collections were exchanged for objects from expeditions at other museums.

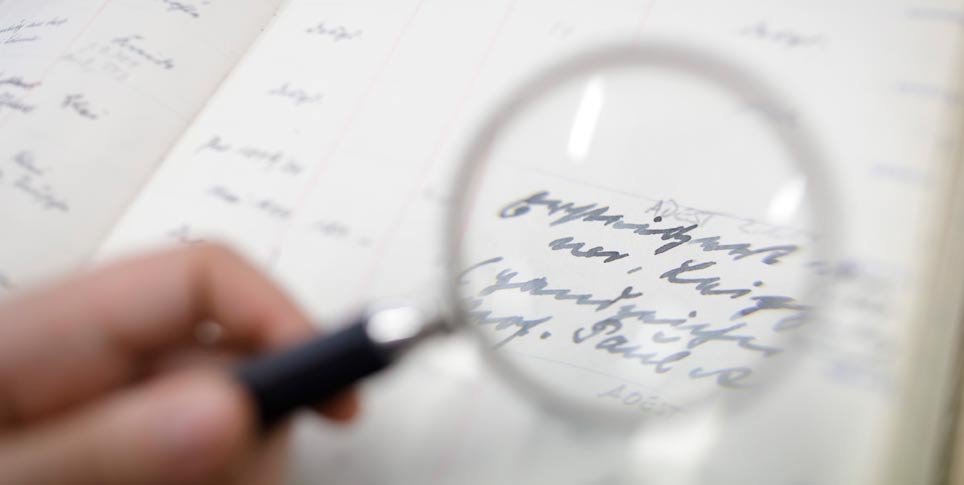

Preuss himself inventoried the objects he acquired, and that is something special about his collections. The index cards he labeled hold valuable, detailed information that complement the publications. In general, the expedition undertaken by Konrad Theodor Preuss was documented in exemplary fashion. The historical files, which have since been converted to digital formats, include travel plans and correspondence to the head of the America collections at the Royal Museum of Ethnology, Eduard Seler.

Will the return of the masks create a gap in the museum’s collections?

Returning the two masks is the right thing to do. The Ethnologisches Museum of today no longer has the universalist ambitions pursued by its founding director Adolf Bastian at the end of the nineteenth century. So there can be no question of a "gap" that will open up by returning the masks.

On the other hand, however, there is one important aspect that has not yet been taken into account. The masks are going to the Colombian state, and in particular to the Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia (ICANH), which is responsible for archaeological artifacts. On the Colombian side, the parties involved in the reclamation of the masks were the Colombian Embassy in Berlin, the Cultural Department of the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, ICANH and the spokesman of the Kogi, José de los Santos Sauna, who has since died of COVID.

The two masks that the Ethnologisches Museum are returning to the Republic of Colombia are part of a group of pre-Columbian masks that are used to this day by the mamos in their rituals. Of course, since the ritual paraphernalia is linked to the founding of temples, I would hope that the masks can eventually be returned to the Sierra Nevada.