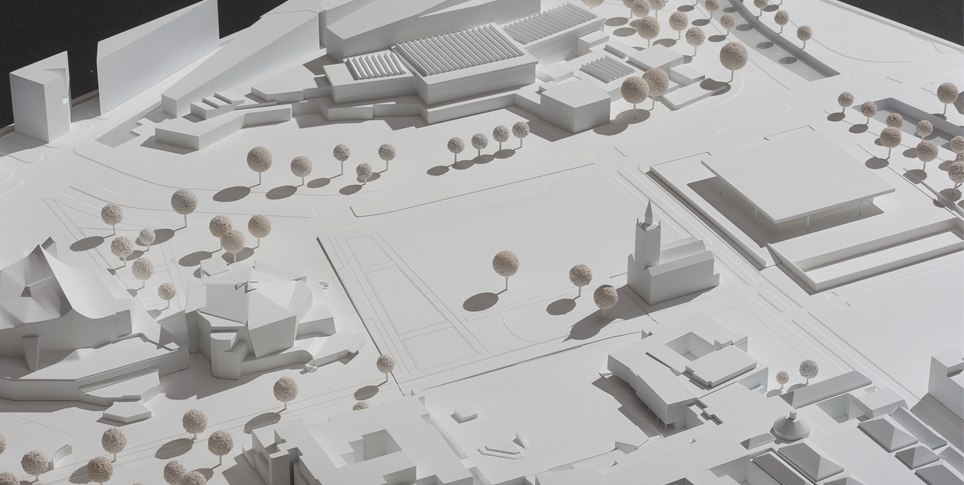

Since 2022, the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library) has been pursuing the research project "The Art Histories and Stories of the Tiergarten Quarter" with funding from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media. Prior to 1945, the quarter around today's Kulturforum was an area of considerable arts-related activity and home to many artists, but the history of the neighborhood was largely forgotten after the war. The aim of the project at the Kunstbibliothek is to reconstruct this history, bring together existing research results and build on them through new studies of the available sources.

The focus is on the magnificent era at the beginning of the twentieth century, when the Tiergarten quarter with its cultural networks grew into a center of modernity, the arts trade, fashion, photography and interior design. This unique cultural heyday came to an end after 1933 as the Jewish residents were persecuted, robbed and murdered by the Nazis, and the quarter was largely destroyed during World War Two.

During the "Day in the Gardens" on September 3, 2023, the project team of Gesa Kessemeier and Joachim Brand will take you on a trip back in time to the Berlin of the 1910s and 20s and trace the footsteps of the forgotten residents of the old Tiergarten quarter. Previously unknown biographies help to fill out the portrait of a fascinating, close-knit neighborhood with a passion for art. They also demonstrate that, a good one hundred years ago, Matthäikirchstrasse was already a "Kulturforum."

A building and its owner

Built in 1870/71, the luxurious apartment house at Matthäikirchstrasse 4 exemplifies the history of this art-minded district. From 1900 onward, it was owned by the fashion journalist and author Julie Elias, whose father was a banker. Beginning in 1890, she lived on the third floor with her husband, Dr. Julius Elias, a historian of art and literature. Their large apartment was a popular gathering place for denizens of the art world.

Photo: The building Matthäikirchstrasse 4 (Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Photo Library, ZI-0178-02-3-252838 / Photo of the Staatliche Bildstelle).

"The couple Julius and Julie Elias occupied a special place [in the neighborhood]," noted the actress Tilla Durieux in her memoirs written in 1971. "They lived across from us..." Tilla Durieux and her husband, the gallery owner Paul Cassirer, often visited the Elias household. Though it was once a radiant center of attention on Matthäikirchplatz, hardly anyone these days knows where the Elias building was located. It stood in the middle of what is now the "piazzetta," the entrance area to the museums at the Kulturforum. Today, there is no trace left of the elegant "brownstone buildings in French villa style," the former residents, or the art-minded neighborhood.

Julius and Julie Elias were two of the prominent, early twentieth-century figures who were forgotten after 1945 but are now being rediscovered and rewritten into our cultural memory. The recovery of such history is providing fascinating insights into a lost world, an "Atlantis of modern art" in the Tiergarten quarter.

Julie Elias – "One of the most endearing figures from the literary and artistic world"

When fashion journalist Julie Elias (1866–1943) – described by art critic Max Osborn as "one of the most endearing figures from the literary and artistic world" – and her vivacious husband Julius (1861–1927) extended invitations to one of their "gastrosophic evening parties" at Matthäikirchstrasse 4, the cultural elite of Berlin paid a visit, and it promised to be an artful evening in a number of ways.

Amidst paintings by German and French impressionists such as Monet, Manet, Cézanne, Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt and Lovis Corinth – a detailed list can be found among the heirs' claim for compensation – the Eliases dined with their painter friends Liebermann, Slevogt, Orlik, and Corinth, along with gallery owner Paul Cassirer and other welcome guests, such as Max Osborn, Gerhard and Margarete Hauptmann, Henrik Ibsen, Edvard Munch and fashion journalist Elsa Herzog. Those in attendance carried on passionate discussions of modern painting, literature, fashion and design while enjoying culinary delicacies and fine wines.

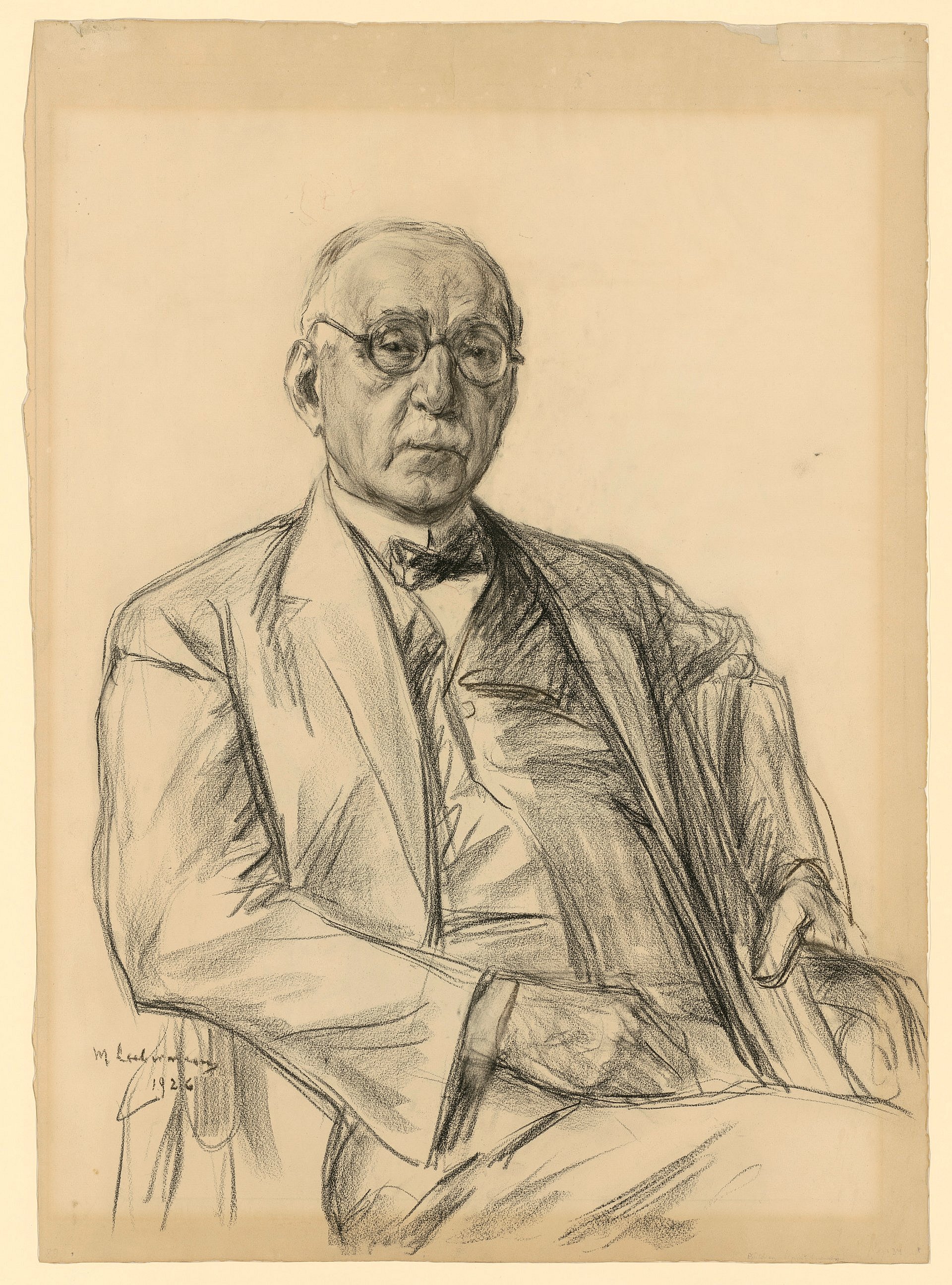

Julie Elias was considered a "virtuoso of first-rate conviviality." "The lady who gifts us with the most graceful and charming essays on fashion also has the best taste. Not just in matters of fashion, but also in her bill of fare," commented the magazine Querschnitt in 1925. Networks were formed; friendships were cultivated; and jobs were commissioned. Max Liebermann painted portraits of Julius and then Julie Elias. Lovis Corinth created a portrait of their son Carl Ludwig. On a number of occasions, Julius Elias wrote commentaries on Liebermann's art that were printed by Paul Cassirer's publishing house. A portrait of the painter hung next to those of the Elias family. In 1925, Julie published a gourmet cookbook with the apt title The Art of Cooking, which she dedicated to Liebermann, whose daughter Käthe had begun renting rooms in the large Matthäikirchplatz building owned by the Eliases in the 1930s.

In keeping with the special character of the district, which had grown into a center of the art trade, interior design, haute couture and fashion photography since the turn of the century, Julie Elias was passionate about not just fine art but also applied and performing arts – especially fashion and theater. In her column "Spotlight on Fashion," which she wrote for the Berliner Tageblatt, Elias reveled in painterly worlds of color and vivid imagery. She waxed lyrical about Berlin "fashion artists" like Olga de Bayer, friend of Emil Orlik, and the salon painted by Orlik in the neighboring Bendlerstrasse, and about new shades of red, in which the afternoon dresses and evening gowns of the Hess fashion boutique "burn and blaze." In 1926, she wrote about three evening dresses in gold and red hues that reminded her of "the rosy dawn of beautiful summer days."

She was also eager to note costumes in theater performances, such as a silver lace dress "with a spiral winding around the torso," and a "white velvet cape with silver lamé lining" by her neighbor Johanna Marbach, who lived in Tiergartenstrasse and had a fashion shop in Lennéstrasse; these were pieces, she wrote, that "well-informed observers would never forget." "Frau Marbach has really created a work of art," she concluded.

Elias was a master of vivid descriptions of a literary quality. In the days of black-and-white photography and newspaper articles without pictures, her characterizations immediately brought the models to life in the mind's eye of the reader – like the dress with the "moonlight blue paillettes" that lie "like scale armor around the slender body of the wearer," and the evening dresses that "flash and sparkle: now black as night, now blue like the sky, now white like ice crystals."

Tilla Durieux in a silver lamé dress by Johanna Marbach (Kunstbibliothek – photo by Becker & Maass). The studio of photographer Marie Flatow, née Boehm, owner of Becker & Maass, was located at Bellevuestrasse 5 beginning in 1914.

An art-loving neighborhood

The Eliases were in the best company, surrounded by an illustrious and art-loving neighborhood. At the turn of the century, there were more than 36 private art collections in the vicinity of the Lenné Triangle, Matthäikirchstrasse and Tiergartenstrasse. It was a neighborhood where modern trends in art encountered admirers of the Old Masters; where Louis XVI furnishings met ideas from the Viennese workshops and the Deutscher Werkbund; where enthusiasm for Paris encountered the growing self-confidence of Berlin; where tradition met modernity.

People collected paintings, drawings, sculpture, porcelain, faience, books and furniture – as the Handbook of the Art Market impressively documented in 1926 with innumerable addresses from the Tiergarten district. In 1912, there were 17 millionaires living in Matthäikirchstrasse – either in their own houses or as tenants in large, 15-room apartments full of art and antique furniture. The street was home to banking families like the von Wassermanns, department store owner Georg Wertheim and the industrialist Oscar Huldschinsky.

The buildings and houses in Matthäikirchstrasse were full of art. The street was lined with excellent collections and private galleries like the one owned by Oscar Huldschinsky (Old Masters and sculptures, Matthäikirchstrasse 3a). "It was the perfect reflection of its era," said contemporaries. They also described it as "one of the richest and most beautiful collections in Berlin." A Raphael adorned Huldschinsky's study.

In the home of Max and Olga von Wassermann at Matthäikirchstrasse 6 (where the Kunstbibliothek now stands), there were paintings of German impressionists, drawings and Chinese porcelain. Nearby (Sigismundstrasse 1), Charlotte Fürstenberg-Cassirer collected "modern art," while Dr. Ernst Feist-Wollheim's preference (Matthäikirchstrasse 25) was "old art." Max Neulaender (Matthäikirchstrasse 26), who hailed from Munich and owned the company "Hans Stobwasser," owned a Canaletto.

The art dealer Paul Cassirer (1871-1926) played a central role in this neighborhood. In the 1900s and 1910s, he lived at Margarethenstrasse 1 and had an unobstructed view of Matthäikirchplatz and the Elias building. Early on, Cassirer turned neighbors, friends, family and deep-pocketed customers on to French and German impressionism. In this, reports Tilla Durieux, he had the energetic support of "Dr. Julius Elias," whom she described as a "campaigner for Cézanne und Van Gogh." Another neighbor passionate about modern art was Van Gogh enthusiast Margarethe Mauthner (1863-1947), who had grown up at Matthäikirchstrasse 1 and in 1904 translated Van Gogh's letters for Bruno Cassirer Verlag.

Initially, collectors who took Cassirer's advice, such as Margarete Oppenheim (who lived at the corner of Victoriastrasse and Margaretenstrasse until 1912) were considered "crazy" by their own families "for buying so many of these dreadful modern paintings," wrote the Mendelssohn relative and historian Felix Gilbert. "During the 1920s, however, this contempt gradually gave way to admiration for the courage they had shown in following nothing but their own taste at such an early stage."

The art-filled environment and the artistically oriented family homes inspired the younger generation, too: Annie von Wassermann (*1904), who grew up amidst luxurious furniture, porcelain, faience, Old Masters and modern painting, was a promising sculptor at the end of the 1920s. She was described by Renée Sintenis as "exceptionally gifted." During the same years, Oscar Huldschinsky's son Paul Oscar (*1889) made a name for himself as an interior designer in Berlin, before he emigrated and became a respected set decorator. Of his work on the film Gaslight with Ingrid Bergmann, he remarked: "I just arranged the set the way we lived at home."

Both of them were part of the "lost generation," however. Paul Oscar Huldschinsky died in the United States in 1947 at the age of 57, not long after decorating Thomas Mann's home in the Pacific Palisades. In the 1930s, Annie von Wassermann exhibited her works at the Secession exhibitions in Berlin and Munich and in a solo exhibition in Paris. Ultimately, however, she was unable to maintain the momentum of these early successes. After she emigrated to the United States, she worked as a translator. She died in Switzerland in 1979.

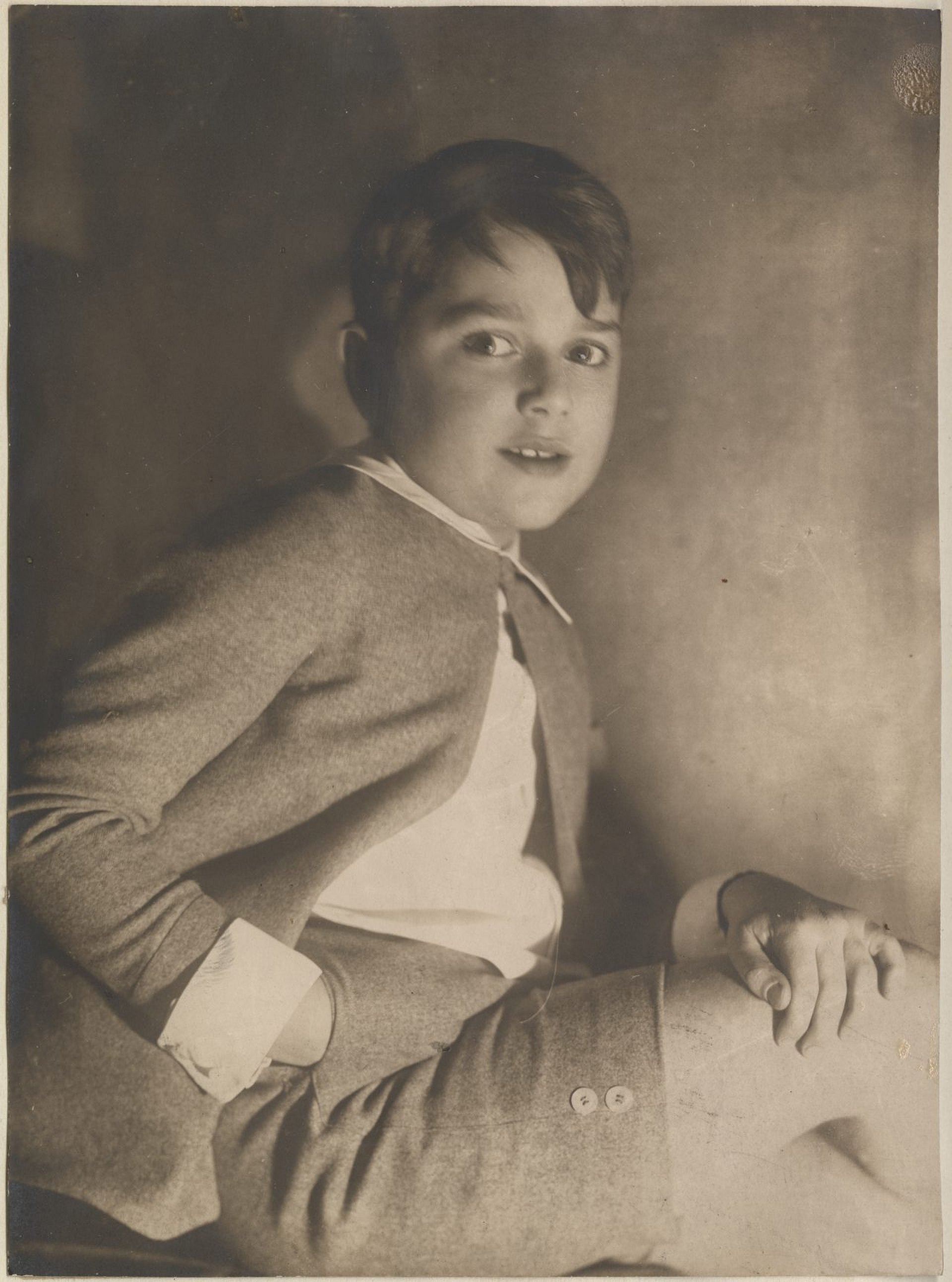

Paul Oscar Huldschinsky.

Photo: ullstein bild

Artistically-minded tenants at Matthäikirchstrasse 4

As historical address books show, the tenants selected by Julie and Julius Elias at Matthäikirchstrasse 4 also had a great proclivity for art and were themselves representative of the inspiring neighborhood in which they lived. The large corner house had belonged to Julie Elias's father since the 1880s, and at the beginning of the twentieth century, spacious apartments were rented there by fashion entrepreneur Fritz Adam (from 1912 to 1924); the interior designer Ilse Dernburg (from 1914 to 1930/31) – a granddaughter of feminist and suffragette Hedwig Dohm and cousin of Katia Mann – and her sister Käthe Rosenberg, who translated for S. Fischer Verlag; the Preussisches Staatstheater actress Lucie Mannheim (from 1920 to 1933/34); and, during the 1930s until her emigration in 1938, Käthe Riezler, the only daughter of Max Liebermann, along with her husband, the former diplomat and philosopher of history Dr. Kurt Riezler, as well as Max Liebermann's charming granddaughter Maria (*1917).

Fritz Adam (1879–1936) in particular drew inspiration from his proximity to the Elias family and their artist friends. In 1924, he launched a large exhibition devoted to the subject of "sports in art" at his fashion store "S. Adam" in Leipziger Strasse. Designed with the support of graphic artist Louis Oppenheim, the show featured seventeen rooms presenting modern sports. The exhibition was rounded out by historical and contemporary sports illustrations arranged by the painter Fanny Remak. "The greatest artists of our age prefer sports-related themes as their subjects. Who hasn't seen Max Liebermann's magnificent pictures of riders on horseback, for example, or his shimmering tennis courts, inspired by players clad in white beneath the summer sun," commented the Berliner Tageblatt. "Slevogt's boundless imagination is captivated by the animated scene at the racetracks. Unerringly rendered by his expert hand, the horses seem to fly across the track. To the great delight of all Berliners, Ulrich Hübner often likes to show us the tumult of the sailing yachts on the Havel and the Wannsee. (...) While elsewhere, the sculptor di Fiori presents the sport of boxing, which has only recently taken root here in Germany. On the walls, pictures by E. Oppler, Büttner, Paeschke, Finetti, Dix and many others demonstrate how eager modern artists are to render sports-related subjects, and how skillfully they do so."

Creative women in the Tiergarten district

Research into the Tiergarten district has uncovered remarkably many previously unnoticed women in creative professions, above all in the applied arts. In the 1920s, they were icons of their trades. After 1933, many of them were persecuted by the Nazis as Jews, robbed and forced to emigrate. Some, such as the photographer Marie Flatow (1872–1943), owner of the photography studio Becker & Maass, hundreds of whose fashion shots are now held at the Kunstbibliothek, were deported and murdered, and the memory of them deliberately blotted out.

"Fashion artists" like Johanna Marbach (Lennéstrasse 3) and the fashion boutique Clara Schultz (led by the creative team of Louise and Anneliese Busch, first at Potsdamerstrasse 129/130, and from 1927 onward, Tiergartenstrasse 15) produced visionary stage costumes for Tilla Durieux and the fashion icon Fritzi Massary. In the early 1920s, eleven haute couture shops lined the Lenné Triangle and Bellevuestrasse, in the immediate vicinity of well-known art dealers and interior design stores.

Interior designer Leni Michels-Fougner (ullstein bild – photo by Atelier Eberth). The photographer Anny Eberth was a neighbor from the Tiergarten district. From 1918 on, she ran a studio for fashion and portrait photography at Lennéstrasse 5.

Interior designer Leni Michels-Fougner (1880–1963), a long-time resident of Matthäikirchstrasse 23, was considered a "master of interior furnishings" and a "spatial artist." As owner of the Antike Wohnräume at Bellevuestrasse 6 (later Hohenzollernstrasse 13), she furnished apartments and houses in the Tiergarten district with furniture, objects of art and antiques. She created set decorations for Fritzi Massary and equipped entire country homes with antique furniture and historical "Dutch panneaux" with landscape scenery, old Chinese wallpapers, Venetian mirrors and historical furniture – work that was very well received.

Michels-Fougner was in the best company with neighboring firms like Hans Stobwasser. Künstlerische Wohnungsausstattungen, which had a business address at Matthäikirchstrasse 26, or the interior designer Ilse Dernburg (1880–1965) at Matthäikirchstrasse 4, who was the same age, was likewise attributed "exceptional talent, outstanding drawing skills, artistic experience and taste" and had worked for many years for Paul Schultze-Naumburg's Saalecker Werkstätten at Victoriastrasse 23 before going into business herself. One thing these creative personalities all had in common was a "large and wealthy circle of acquaintances in Berlin" to whom they had "ample opportunity" to display their talents, attested Dr. Leo S. Gutmann, who was director of the Danat Bank in Berlin until 1931.

After 1933: indiscriminate persecution and destruction of a legendary milieu

After 1933, all of the prominent tenants of Matthäikirchstrasse 4 were persecuted by the Nazis as Jews and forced to emigrate. Julie Elias was forced to sell her building to the city of Berlin. General Building Inspector Albert Speer had planned to have it torn down, along with everything else on the street, to make way for the monumental – but ultimately unrealized – new site of the "Oberkommando des Heeres" (Army High Command). Instead, the building remained a place for art, but under different conditions: The imposing structure was eventually assigned the address Matthäikirchplatz 2, and from the mid-1930s onwards, it accommodated an office and exhibition rooms maintained by the Protestant Kunst-Dienst ("Art Service"), a body that was co-financed by the Ministry of Propaganda and was actively involved in the liquidation of "degenerate art." Exhibitions of "German artistic craftwork" were shown there with the intention of shaping public tastes. These included, as late as 1944, the exhibition Art and Fashion, "a mirror image of German cultural production." On April 29, 1945, the building was destroyed by fire bombs.

The fates of the residents are haunting, and they provide evidence of not just the destructive force of the Nazi regime but also the courage to resist it. In November 1938, for example, after the forced sale of the building at Matthäikirchplatz and the difficult struggle to acquire a visa that would save them, Julie Elias and her son, the lawyer Dr. Ludwig Elias (1891–1942), managed to flee to Norway, where they built a new life with the help of Norwegian friends. After the German occupation in 1942, however, Ludwig Elias was arrested, deported to Auschwitz and murdered there. Julie Elias, who was seriously ill, was able to stay in Norway and died in Lillehammer in 1943.

In 1934, the actress Lucie Mannheim (1899–1976) emigrated to London, where – in the employ of the BBC – she played an active role "in the fight against Nazi tyranny." Her anti-Hitler song to the melody of the pop hit Lilli Marlen is still moving today – "Hitler, the man of blood and fear, hang him up at the lantern here!“ In 1953, she was awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Fritz Adam (1879–1936), who lived at Tiergartenstrasse 8 beginning in 1925 and later at Matthäikirchstrasse 28, emigrated to England with his family. He was unable to overcome the persecution, emigration and loss of his famous fashion company. He died in London in 1936. His son Klaus Adam, who was born at Matthäikirchstrasse 4 in 1921, achieved a successful career in England. In the 1960s, he became a leading production designer for the early James Bond films under the name Ken Adam. But the memory of his childhood in the Tiergarten district never left him: While working on the film Taking Sides in the year 2000, he designed a set from the 1930s in the style of his parents' grand, upper-class apartment in the Tiergarten quarter. His artistic estate is held at the Deutsche Kinemathek on Potsdamer Platz.

"From wall to mouth"

After emigrating to the United States with her husband and daughter in November 1938, Käthe Riezler (1885–1952), the daughter of Max Liebermann, wittily described her erstwhile neighbors' manner of existence. In exile, she remarked sarcastically, many of the former residents of the Tiergarten district lived "from wall to mouth."

She was alluding to the fact that art which had been taken abroad by those former residents – after they had paid huge compulsory charges to the German Reich to obtain a "certificate of good standing" from the tax office – was a means of subsistence for many of them. In the 1950s, this was confirmed in statements made to the Entschädigungsamt (Compensation Office) from New York by Leni Michels-Fougner and Katharina Feist-Wollheim (Matthäikirchstrasse 25), widow of the art collector Dr. Ernst Feist-Wollheim, who was detained in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1938 and died there in January 1939 as a result of the serious injuries he suffered – frostbite, and an untreated case of blood poisoning.

In the case of Julie Elias and her son Ludwig, immigration to Norway was secured not only via the support of the Norwegian Foreign Minister Halvdan Koht but also with the help of more than thirty paintings. Gustave Courbet's Vendange à Ornans, which Ludwig Elias sold in Switzerland in 1938, provided them with foreign currency that could not have been transferred out of Germany without deducting a compulsory 96-percent levy. Five works of French impressionists that had previously hung at Matthäikirchplatz, paintings by Toulouse-Lautrec, Manet, Monet, Pissarro and Cézanne, served as security and were given on loan to the Norwegian National Museum in Oslo in the year 1939/40. These are all forgotten stories of the art from the Tiergarten district.

More historical research and detective work needed

A great deal of historical research and detective work are still needed in Berlin to add more detail and breathe yet more life into the fascinating picture of the art-loving Tiergarten district, a world deliberately consigned to oblivion after 1933. The research is already endowing the site of today's Kulturforum and the future location of the new museum of twentieth-century art with a previously unimagined depth and significance.