Michaela Scheibe in search of lost books and their unknown owners

Imagine wanting to make a mystery movie. The setting is the endless stacks of a famous library. The detective is a woman, of course; a shrewd lady who searches not only for lost books but also for their unknown owners.

Drei Engel mit dem Christuskind © SMB, Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst/A. Voigt

Our book detective is Michaela Scheibe, who works in the Department of Early Printed Books in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library). She loves to travel, has a gravelly voice and fly-away hair, and the first thing she does in the elevator is tell a joke. The elevator loudspeaker makes a surreal announcement: “Twelfth book floor.” The shelves up here in the floors of the stacks support the whole building, not only the books. This house can never do anything but store books. Even in a future when maybe no one reads anymore, this building will stand on Unter den Linden as a greeting from the past. Three million greetings, to be exact. Greetings in the form of books. And each one has a story. What that story is, however, is often a matter for years of research and detective work. The odor of old paper wafts through corridors that seem to go on forever. During the NS period, some of these books were stolen from private Jewish libraries, worker society libraries, Masonic lodges or scientific institutes. All of them have a long history. Some were placed in ostensibly safe places during the war and then brought back to Berlin. Others never came back. Books are like people. If they could speak they would tell of the labyrinth of guilt under the NS, of farewells, loss and death. But they can’t speak. Only whisper in their own language. Scheibe can understand what they whisper.

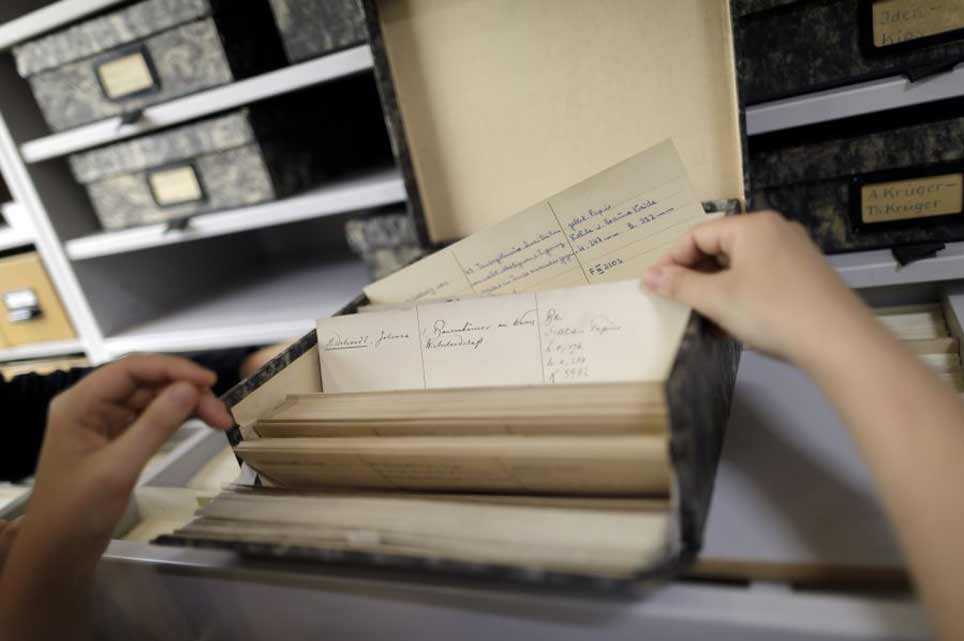

After all, books are not the only influences on their readers. Readers–all owners, in fact–influence their books with marginal notes and dedications, with beautifully made bookplates, with marks and stamps. These are all signposts that lead to the former owner with a little luck. Scheibe has a detective’s approach: she holds black stamps under UV light, deciphers the pictures in bookplates and compares handwriting.

A medievalist, she learned the language of books by dealing with medieval manuscripts. She gave herself over completely to her fascination when she reconstructed the library of the Pietist Johann Friedrich Ruopp in Franckeschen Stiftungen zu Halle (Francke Foundations in Halle). “My job is very haptic. We don’t just deal with abstract texts but also with the whole materiality of a book as such. Books are wonderful sources; they are charming and tell stories.”

The Staatsbibliothek has been systematically researching and exploring dubious acquisitions since 2006. Scheibe found her niche in provenance research even though she has to distance herself from the personal tragedies she encounters there. “That’s not always easy. When I see that a book was confiscated from Jewish owners in 1942 or later, I know that the owners were probably murdered.”

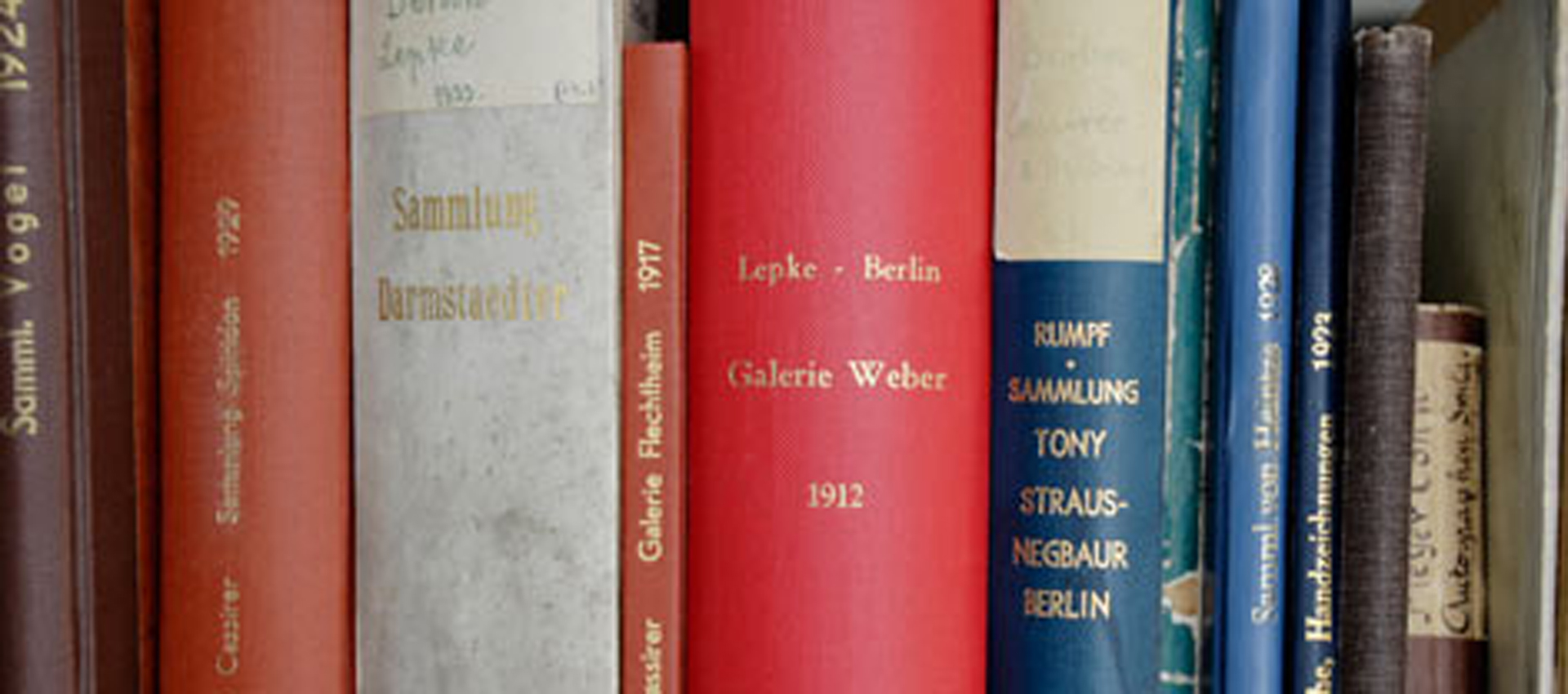

Tracing the owners often takes years of work. There are three million volumes in the Staatsbibliothek that were printed before 1945, and Scheibe first has to filter out the books that are potentially NS plunder. Of course, there is no card file labeled “Plundered.” Instead, there are 20 meters of large-format, handwritten acquisition registers. These entries are first examined for suspicious signs. Her team is lucky to be able to refer back to Karsten Sydow’s previous research. Of 375,000 entries, he was able to filter out 20,000 suspicious acquisitions. Eleven thousand of them have been checked and 2,200 have been returned to their rightful owners.

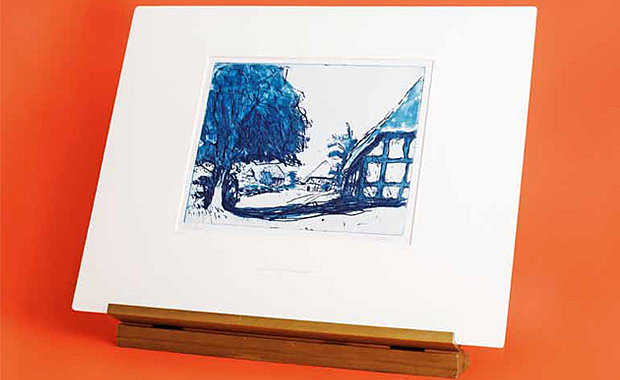

Scheibe opens an acquisition book: a large register with a marbled cardboard cover. The suppliers are entered in red tables. The team looks for all copies of the registered book title in the online catalogue, then inspects the books for the acquisition number that was noted in the acquisition register. When they find the number, they inspect the book for any traces of previous owners. But the book could also have been burned during the war, or it could be in Moscow or Krakow now. “After the war, the Allies took entire libraries away with them. The fact that they are holding on to property stolen by the NS is only just starting to dawn on them.” If Scheibe finds an entry referring to a book that was removed from the Staatsbibliothek because of the war, her job is finished. Politics steps in. Even in cases where a book is found, the research is not always fruitful: in many cases the books hold no traces of previous owners or the markings cannot be connected with any individual or institution.

Books are charming and tell stories.

The team was especially happy when almost the whole library of the Teutonia zur Weisheit Freemason’s lodge could be returned. “We don’t attach any emotional value to successful restitution. We can’t expect anything from what amounts to rudimentary attempts at restitution.”

How long would it take to research the provenance of all the books? Scheibe considers and then says: “If I could work on it with ten people for one hundred years, then we could do it.” Provenance research is a combination of futility and hope. But Scheibe isn’t working for the headlines. Her goal is to find the historical truth. This requires painstaking detective work. It’s like a good mystery novel. Michaela Scheibe is the ideal heroine.

Michaela Scheibe

Michaela Scheibe was born in Würzburg. After studying history and political science, she worked for the manuscript department of the Staatsbibliothek and completed an librarian internship at the Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek (University and State Library) in Halle. Today she is the assistant director of the Department of Early Printed Books.