The Saulmanns were dispossessed and driven out of the Swabian Alb in 1936. Searching for traces of the past

Perhaps Hermann Taigel is the last one. He caught a fleeting glimpse of her between the white clouds and the high tops of the apple trees. “I still remember the airplane exactly,” he said. When he was a boy, he sometimes saw it against the sky. The man’s voice faltered, and there was only the sound of breathing in the telephone receiver. The former historian of the city of Pfullingen and the author of a standard work on the Swabian dialect does not want to say any more. And no, he doesn’t want to see anyone either. But he did see Agathe Saulmann. Back then, in 1933 or so, when half of the town looked up from their work and looked curiously above the green hills of Echaz Valley. “There she goes, it’s Mrs. Saulmann,” they all said in amazement. Now over 90 years old, Taigel is the last one whose dreams were filled with flying and the lightweight airplane of the factory owner’s wife, which was built by Hanns Klemm from Böblingen.

Designed by Theodor Fischer, the house is now privately owned © Christoph Mack

The village diva

The others in the small town only know the woman from hearsay. They still call her “the Saulmann”– as if she had been a diva. Indeed, “the Saulmann” must have been a commanding figure. The daughter of architect Alfred Breslauer from Berlin, she bought a large house here on the edge of town in 1927 together with her husband. “In a place like Pfullingen? Why?” An elderly, well-dressed lady arched her gray eyebrows. In Pfullingen, someone like Agathe Saulmann would certainly not have had it easy. A woman like her would certainly not have fit into the idyllic place at the foot of the Swabian Alb that seems like an extension of the county town of Reutlingen five kilometers to the north.

After all, Agathe Saulmann sometimes wore checked trousers. In an old picture she is smoking a pipe. And just behind road 6729 toward Gönningen, where the eight-acre field called Schweinhatz starts, she took off with her little Klemm plane. “That would have been too much for the down-to-earth Pfullingers.” The elderly lady arched her eyebrows again. But she said that she had never met the Saulmanns. She only moved to the orchard-filled valley after the war – back then when people claimed not to have seen anything, but sometimes to have heard things.

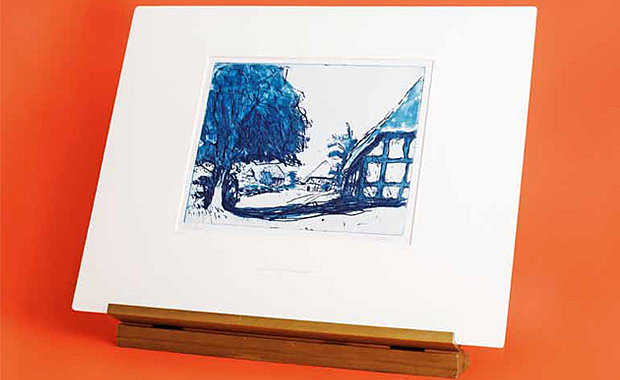

Anyway, blessed are those who have not seen and still believe. Maybe Saulmann knew that too. There was an art collection in Erlenhof, her large house that was built in 1904 by the architect Theodor Fischer, which still stands like a monument on one of the last hills on the edge of town. And there was a small relief in that collection. a work of sacred art from the 15th century. It told of faith, of seeing and remembering: It was created by an unknown artist in southern Germany and portrays the Christ child being carried by three angels. The birth of something divine. An image like this could help make the unexplainable explainable to believers.

A lot of things were inexplicable. Later on, here in Pfullingen as well. It started sometime in 1933. During one of the first boycotts of the Jews, they took Agathe Saulmann’s airplane away from her. Out of the blue, the manufacturer’s eccentric wife suddenly seemed transformed into a threat for many people in Pfullingen. “There were lots of Nazis and anti-Semites here…like everywhere in Germany,” explained Waltraud Pustal, the chairwoman of the Pfullingen Historical Society. But there were hardly any Jews in the town. Up there in the mountains, in Lautertal, there was a small Jewish settlement, according to Pustal. “Here in Pfullingen? Only the Saulmanns.” A file from the 1960s confirmed her statement. At the request of the archive directorate in Stuttgart, a “Documentation on Jewish Fates in 1933/45” was compiled: “Here is your form on Ernst Saulmann, filled out and returned. Apart from him, no Jews lived in Pfullingen between 1933 and 1945,” reported the mayor of Pfullingen to the capital city of the state of Baden-Württemberg.

An unlikely couple

Nobody, just those two. The businessman and the amateur pilot. In October 1927, the managing partner of Mechanischen Baumwollweberei Eningen, a weaving mill for cotton, and his 17-year-younger wife settled in Erlenhof. Surrounded by hedges and old fruit trees, they lived in an idyllic house with crenellations and towers. A short time before, it had been the home of an artists’ colony that was known far beyond the city boundaries. Hermann Hesse and Adolf Hölzel were said to have been among the regular guests. And then came the Saulmanns, an unlikely couple; he was a successful businessman and she was athletic, artistic…and a divorcée.

The house was rumored to have cost them 66,000 Reichsmarks. An acquisition that riled up the envious and the Nazis. It was always the same story. “Just before that the harassment began,” Agathe Saulmann once told a journalist. The stream of factory orders became a trickle, approved loans were rescinded. As if that weren’t enough, there were attempts to agitate the factory employees during the Christmas holidays in 1935. “When Mr. Leger told me on December 25, 1935, that district leader Sponer gave a speech hoping to incite the employees to demonstrate in front of the factory and call for my husband, I sent the weeping man away against his will.”

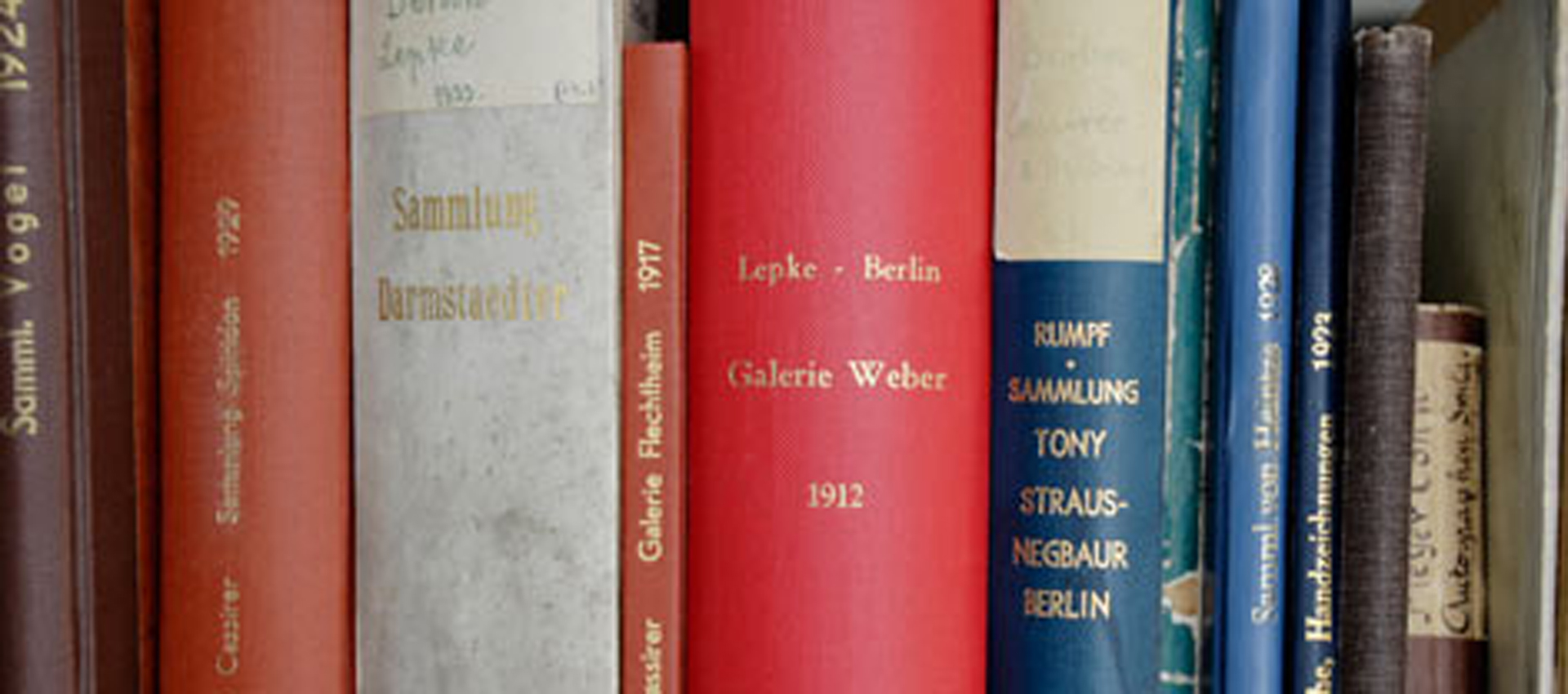

Agathe and Ernst Saulmann fled via Florence to Nice, where they later fell into Nazi hands. In 1936 their factory was impounded, sold at auction, and aryanized. The more than one hundred objects in their art collection were also auctioned off. In 1936, they were sold in three auctions in Adolf Weinmüller auction house in Munich. As was customary then, the previous owners were not mentioned during the auctions. The proceeds from the auction were used to collect the Reichsfluchtsteuer (Reich flight tax), an insidious method of refinancing Nazi terror by which the victims paid the henchmen for their crimes. The Saulmanns were later brought to a concentration camp in France, probably the notorious Gurs in the Pyrenees Mountains. Ernst Saulmann died in 1946 as a result of his imprisonment. Only Agathe would return once, go back to the green hills at the foot of the Alb, to the half-timbered houses and apple trees, to the places where today almost nothing is reminiscent of those terrible days.

But in 1999, five hundred kilometers to the east, the first clue leading back to the Saulmanns’ story turned up. At that time, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin acquired a small relief made of lime tree wood, an unsuspicious sacred object: three chubby-cheeked angels guarding a small, helpless baby above the clouds. The angel group from Ernst and Agathe Saulmann’s art collection; it had once been a great help to all those who had to see to believe. But the small object’s history was still unknown.

Thirteen years later, in September 2012, a search request appeared in the Lost Art online database. Under the number 459418, a law office in Berlin had entered a search on behalf of Saulmann heir Felix de Marez Oyens, a half-brother of Agathe Saulmann’s daughter by her first marriage. The three silent angels and countless other works from the Saulmann collection were being sought. Another five years would pass before the object was connected to the search request. Then everything went very quickly: After the object’s resemblance to historical pictures was pointed out to the Staatliche Museen, comprehensive provenance research was initiated.

Persecuted in plain sight

“The facts were obvious,” said Sven Haase, assistant director of the museums’ central archives, who was responsible for researching the angel relief’s origins. The Saulmanns’ status as victims of persecution was clear from the beginning. Reading the newspaper would have been enough: In 1936, there was a tax warrant announcement in the Reichsanzeiger, the official Nazi newspaper, publicly announcing the confiscation of the Saulmanns’ property. It accused them of owing the German Reich 106,885.75 Reichsmarks in Reich flight tax. It was public persecution.

Today, there is a short comment in the Lost Art database entry: “Amicable settlement.” In fall 2017, the Staatliche Museen restituted the object and then bought it back. The three angels can now be admired in the Bode Museum. They tell far more than a story of adoration and the beauty of Christian art. But was justice redressed with the return of the angels? Agathe Saulmann is not the only one who would have had her doubts. In a spectacular court case after the war–at that time the largest restitution proceedings in the French occupation zone–the manufacturer’s widow fought to get Mechanische Weberei Eningen returned to her. Ultimately, she accepted payment in lieu of her shares in the business.

But there was no way to undo the suffering. A short announcement appeared in the local newspaper, the Eninger Heimatboten, in July 1951: “Mrs. Agathe Saulmann, most recently a resident of Baden-Baden, committed suicide there in the middle of last month.” There were four unsuccessful previous attempts and the reasons for her suicide appeared to be clear to the Heimatboten editor: “Since Mrs. Saulmann had no extreme financial difficulties, it is assumed that manic depression was the cause.”

Anyone who wanted to look at the big picture would have also seen injustice and the unbearable helplessness of a woman dispossessed by the Nazis. Today, there is hardly a trace of Agathe and Ernst Saulmann. Evening is descending over small Echaz Valley. Hermann Taigel, the former historian of Pfullingen, is the last to have seen her. He is one of the last to remember Saulmann and her small airplane. She used to fly through the broad Swabian skies like an angel.

Expelled, Dispossessed, Interned: The Saulmann Heir in an Interview