For 70 years, Victoria of Calvatone was considered lost. Then the work suddenly reappeared in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. How to approach a woman in gold.

The victories were in the past. When General Alfred Jodl signed the unconditional surrender of the German Army on the night of May 7, 1945, certainly no one in Germany needed a gilded goddess of victory. More than 60 million lives, including 27 million citizens of the former Soviet Union – this was the result of a war started by Germany, the most horrific war to date in human history. Wasn’t it logical that at some point after the end of the unimaginable inferno, a statue of Victoria (victory) from the imperial Roman period would be heaved into a Russian truck to be removed from the ruined capital of the fallen Third Reich?

© Museo Civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona

Victoria in art

An ink drawing by Carlo Alghisi from 1879 shows Victoria without wings.

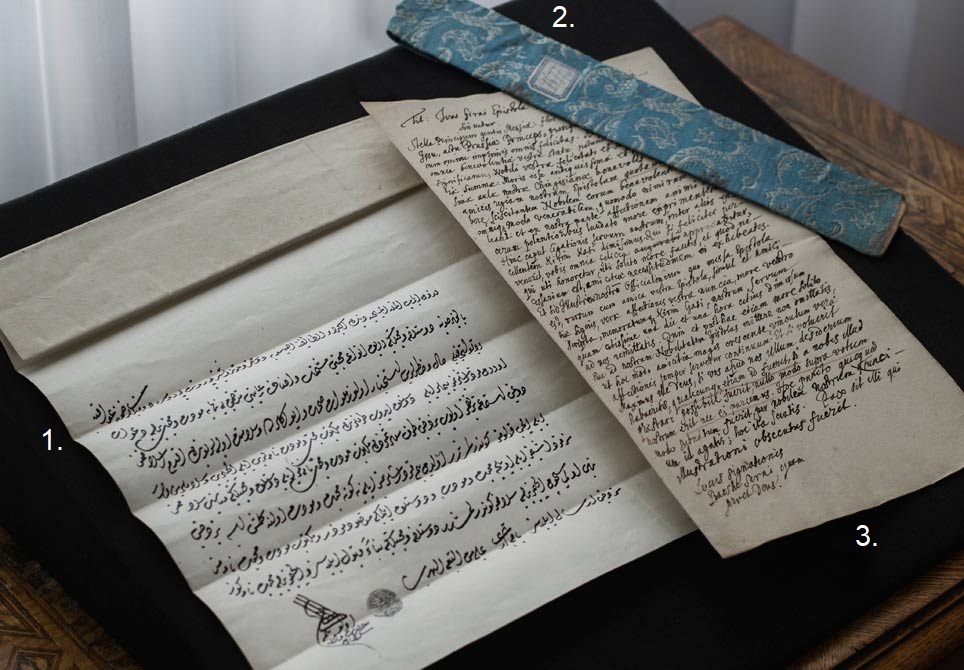

The statue, which was known all over the world as the Calvatone Victoria, was in the Altes Museum in Berlin for almost 100 years. It was considered a gem of second century Roman sculpture. But then the war started and starting in 1939, parts of the collection were moved to the safe room of the Neuen Münze (New Mint) at Molkenmarkt – including Victoria – to protect them from air raids. The statue survived the later conquest and capitulation with relatively little damage.

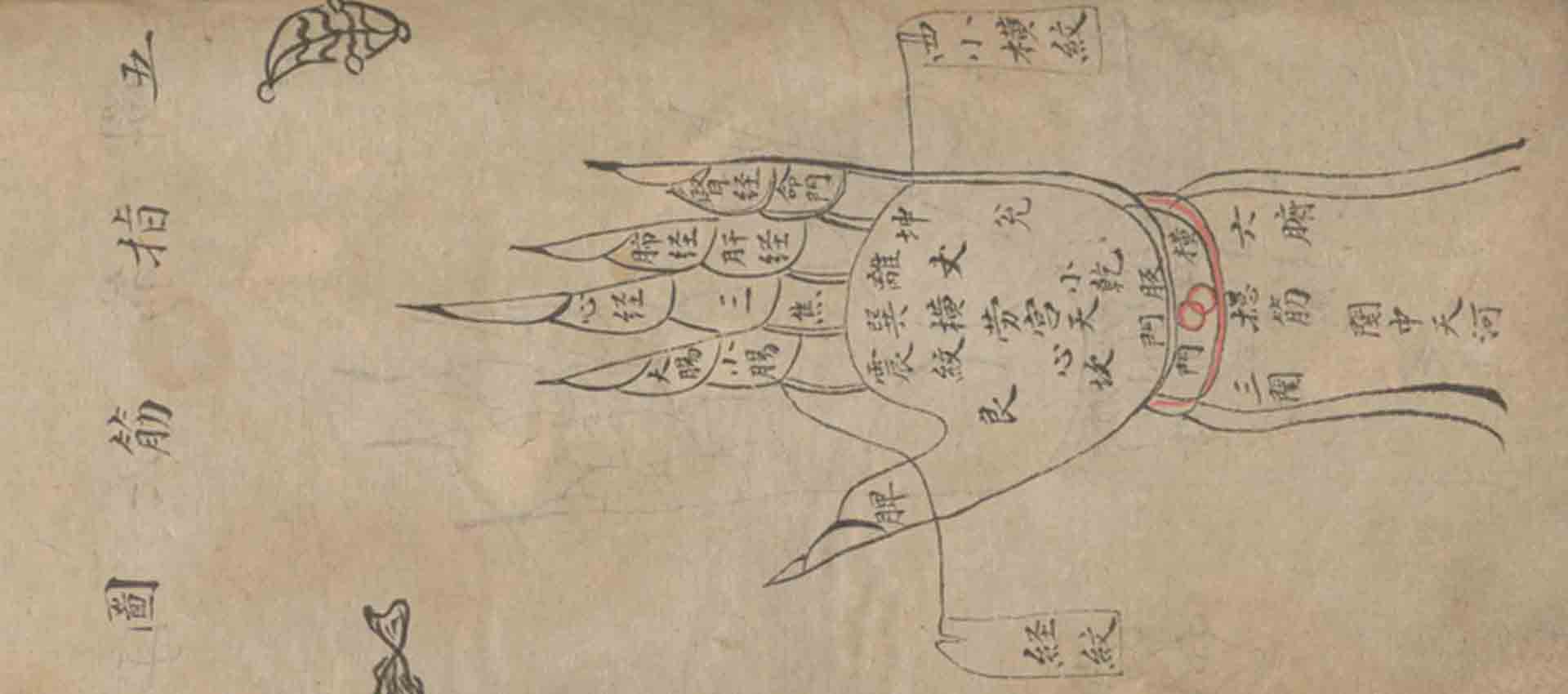

But during the first year after the war, Russian experts specifically remembered the Calvatone Victoria. One of the most important gilded bronze statues from the collections of Berlin museums was taken to the former Soviet Union in 1946 – along with 2.6 million other art treasures. It appeared to be the end of the unique female figure, which was first discovered by Italian farmhands near the city of Cremona in Italy. Five years later, in 1841, was sold for 9,000 Austrian liras to the Royal Museums in Berlin. Victoria floated elegantly over a globe that she hardly seemed to touch with her toes. Her size, quality, and balance had made her an eye-catcher of the antiquities collection in Berlin; numerous copies, including ones in Rome, Moscow, and Cremona, spread her fame throughout the world.

But after she was taken from Berlin, all signs of the 170-centimeter tall goddess of victory, who had once stood on a covered bridge connecting the Altes Museum and Neues Museum, were lost. When the truck reached its preliminary destination with Victoria, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, a fatal error must have been made. Presumably out of haste, the bronze figure was placed in a storage area for 17th century French sculptures.

Anna Vilenskaja, an art historian at what is probably still the most famous museum in Russia, whose areas of expertise include Victoria of Calvatone, has a practical explanation for the error. “The sculpture depicts a European woman’s figure in a sensuous pose, so the people probably automatically thought the gilded woman was from France,” said Anna Vilenskaja with a laugh. Of course, an expert like her knows that the real reasons for the statue’s disappearance may have been far more complicated. The large Roman statue underwent many changes during the 19th century. Restorers in Berlin gave her a new arm and attached heavy wings to her delicate back. So it is likely that in 1946, only experts would have recognized the ancient origins of the dainty sculpture of a woman with unusually long legs. According to Vilenskaja, who has recently researched Victoria’s iconography, the bronze arrived at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg without documents or an inventory number. So it was practically impossible to identify it at that time.

The statue might have remained in storage so if her sister goddess Fortuna had not stepped in for her. While researching in an archive in Moscow in 2016, Vilenskaja’s colleague Anna Aponasenko, a historian from St. Petersburg, discovered documents that revealed Victoria’s fate and location. A stroke of luck for the international museum world, as Vilenskaja said: “From then on it was clear that the historically important statue, which had inventory number 5 according to the documents in Moscow, had to be in storage in the Hermitage Museum. The number was probably lost in the confusion of the war and post-war period.”

This made it possible for professional circles to hear nothing more about “Number 5” for almost 70 years. As far as the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) were concerned, the statue had been lost. But the colleagues in Berlin were notified by St. Petersburg shortly after it was found in the Hermitage Museum. In a joint project agreed between the museum’s director, Michail Piotrowski, and Hermann Parzinger, president of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), research and restoration of the precious find was begun. Since then scientists have regularly traveled back and forth between Berlin and St. Petersburg to uncover the gilded lady’s last secrets.

“This cooperation is immensely important,” said Anna Vilenskaja about a German-Russian cooperation that some might think unusual. A national law passed in Russia in 1996 declared all German cultural assets that were transported to Russia after World War II to be Russian property. In Russian, this is called “compensational restitution.” But talks and agreements that consistently cause difficulty on the political level have long since become normal on the cultural level. Supported by the Kulturstiftung der Länder (Cultural Foundation of the German States), Russian and German museums have been working together closely on the research, restoration, and exhibition of cultural assets relocated as a result of the war despite the assumption that these former German cultural treasures will never be returned to German museum collections.

This applies to the Calvatone Victoria as well. “The longer we study this statue intensively together, the more new questions arise,” said Aponasenko about the intensive cooperation. Ultimately, there were more questions than answers, but some riddles could actually be solved. According to Aponasenko’s colleague Martin Maischberger, assistant director of the antiquities collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin), we can assume that Victoria originally had no wings: “The wings were added in the 19th century, presumably by a restorer in Berlin.” For the German-Russian research team this was an important find. “Now an interesting theory has been postulated that the statue originally did not represent Victoria, but some other goddess: Luna, Aurora, or Diana,” said Maischberger. “In the 19th century there were several precursors and parallels to the practice of adding wings and reinterpreting statues as the goddess of victory.”

If the hypothesis is proven true, it would indeed be an irony of history. A statue that could have become a tragic symbol of the rift between Germany and Russia in the 20th century would become the expression of a unique cooperation between two important European cultural institutions and, on top of it, is probably not a goddess over victory and defeat. Instead, she may well represent grace, splendor, and an ideal of beauty that binds peoples together.

Michail Piotrowski, director of the Hermitage Museum, sums up the confusion surrounding Victoria in a nutshell: “We have so many problems in the world today and everyone should do their job. For people who work in museums, this means researching objects and presenting the results to the public worldwide. Political issues or issues of ownership are clearly of lesser importance.”