SJ Zanolini is a PhD candidate in the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and is currently writing up a chapter of their dissertation that focuses on rice porridge and conducting primary source research to prepare a subsequent chapter on edible fungi. As a research fellow at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Zanolini worked on "Everyday Medicine: Prescribed Diets in early Modern China" from a medical history perspective.

What is your professional background and focus?

I am currently a PhD candidate in the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. My research focuses on “everyday medicines” used in China during the long-eighteenth century. However, prior to embarking on this path of historical research, and preparatory training in Chinese language, I was a licensed practitioner of East Asian medicine. I studied acupuncture and herbology at Dongguk University in Los Angeles, and after graduating I practiced community acupuncture from 2012 onwards in California, and again from 2019-2020 in Maryland.

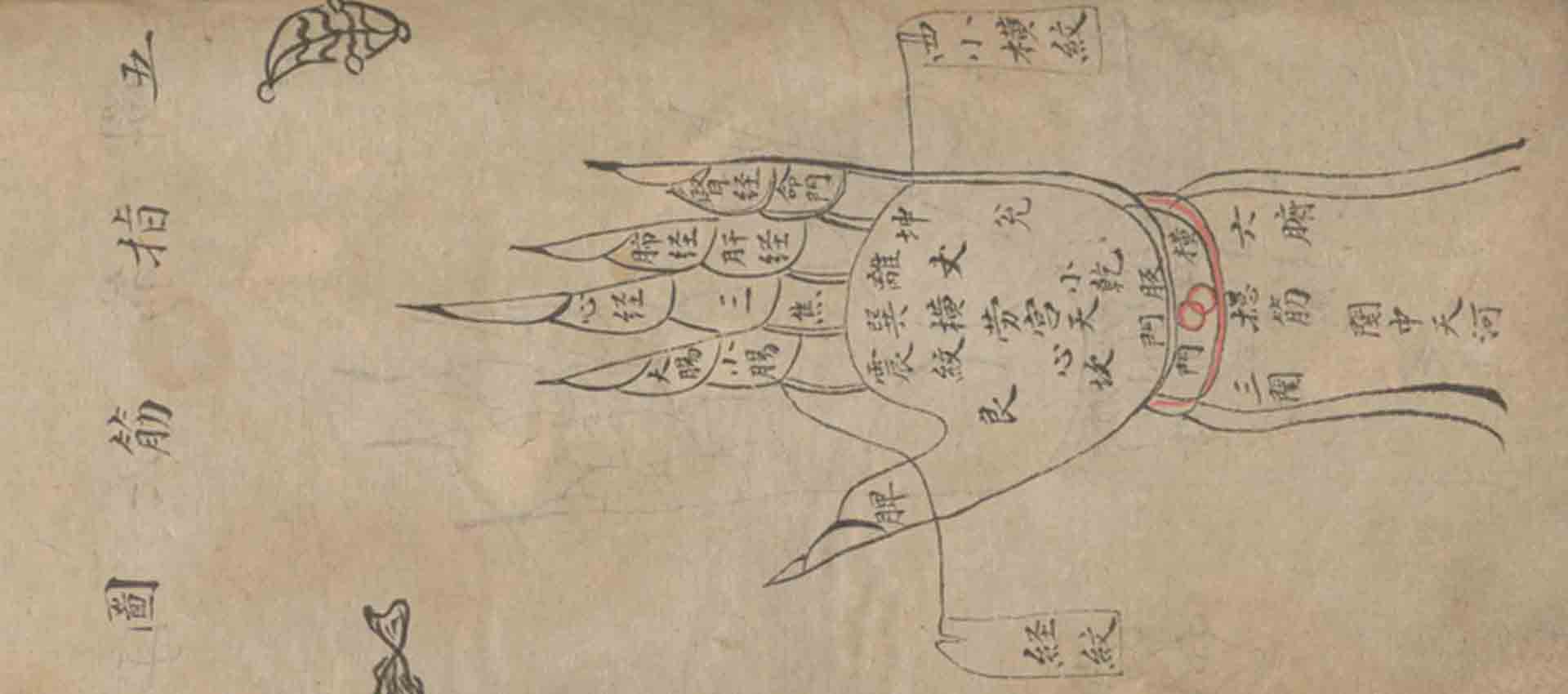

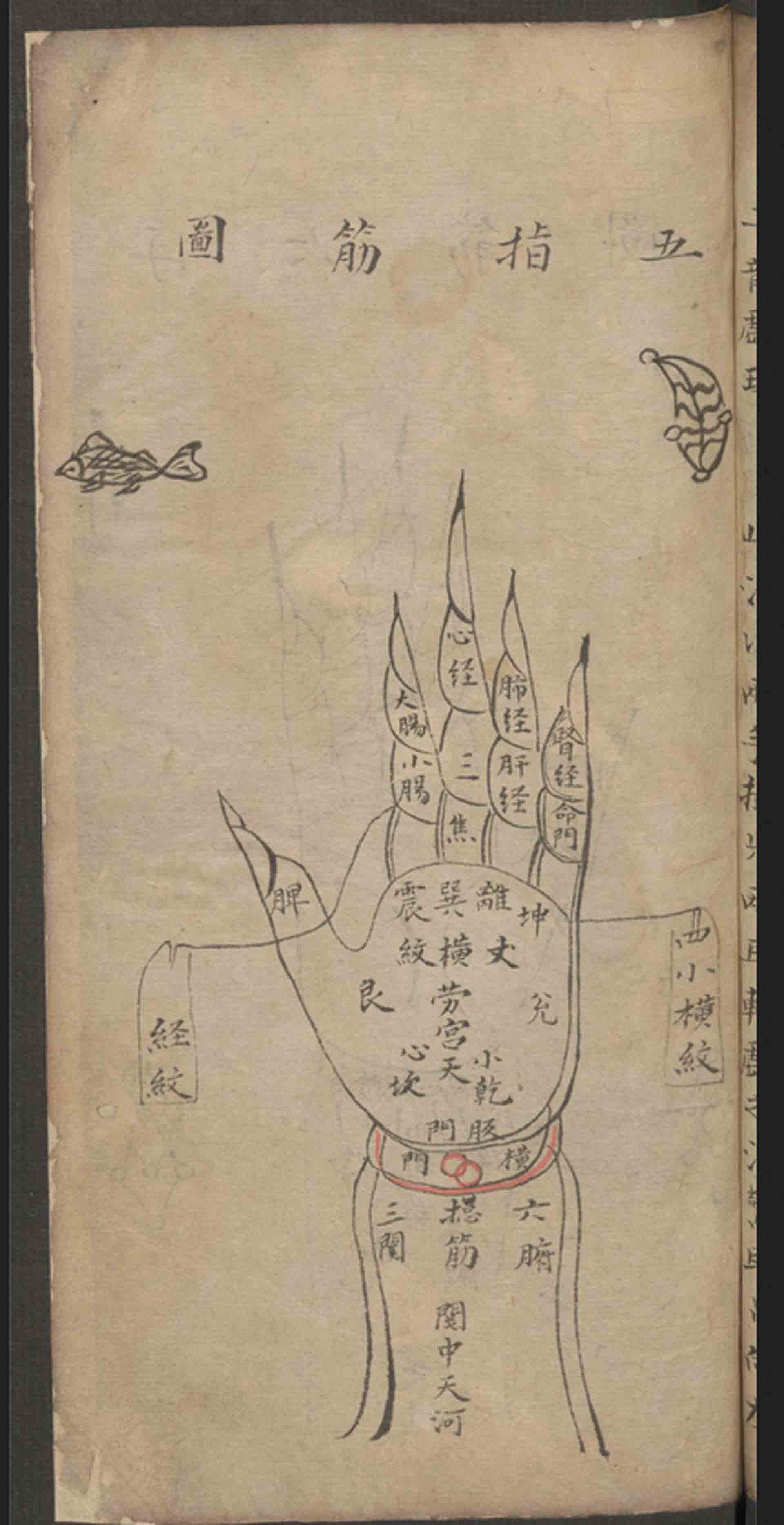

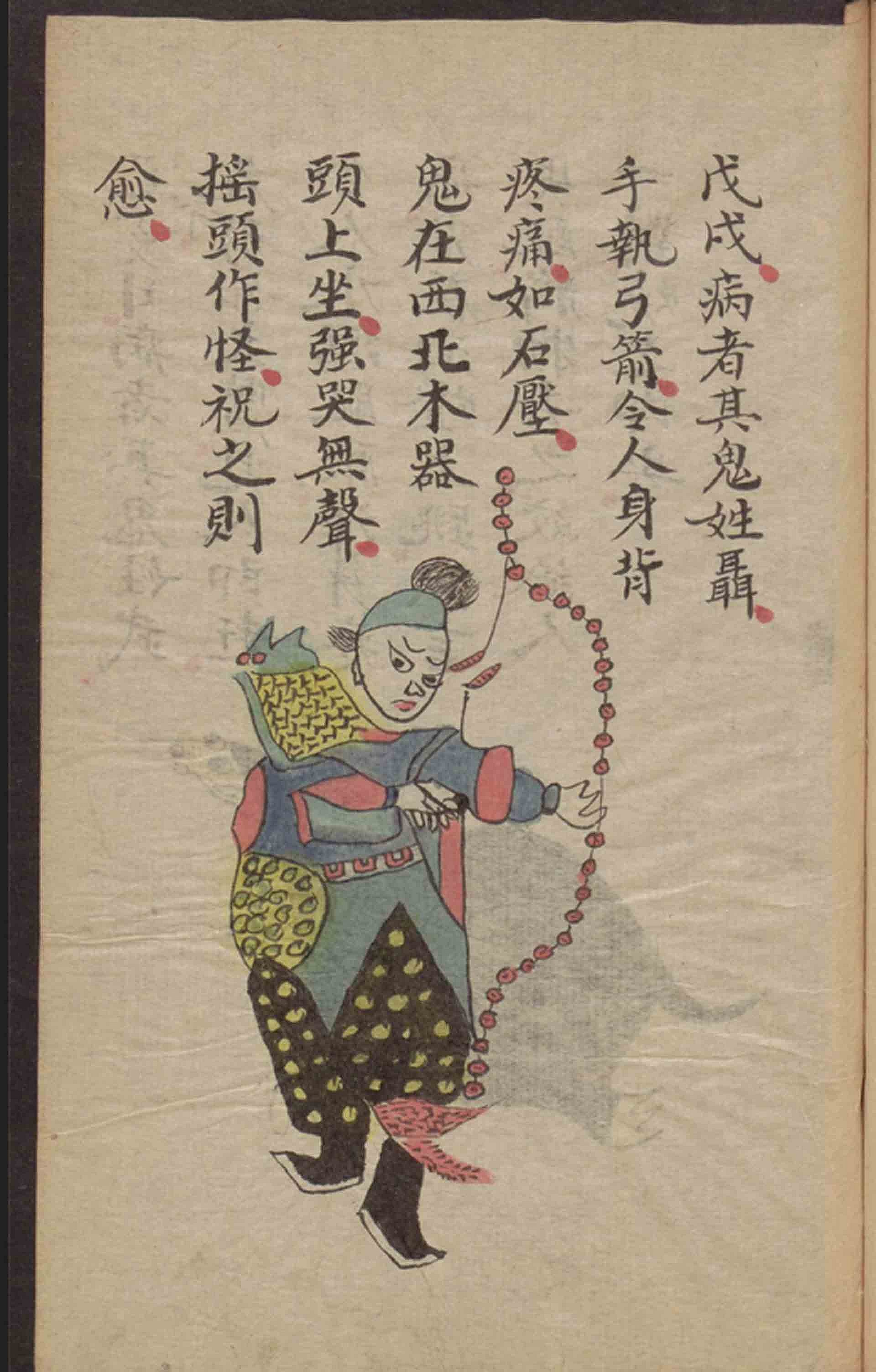

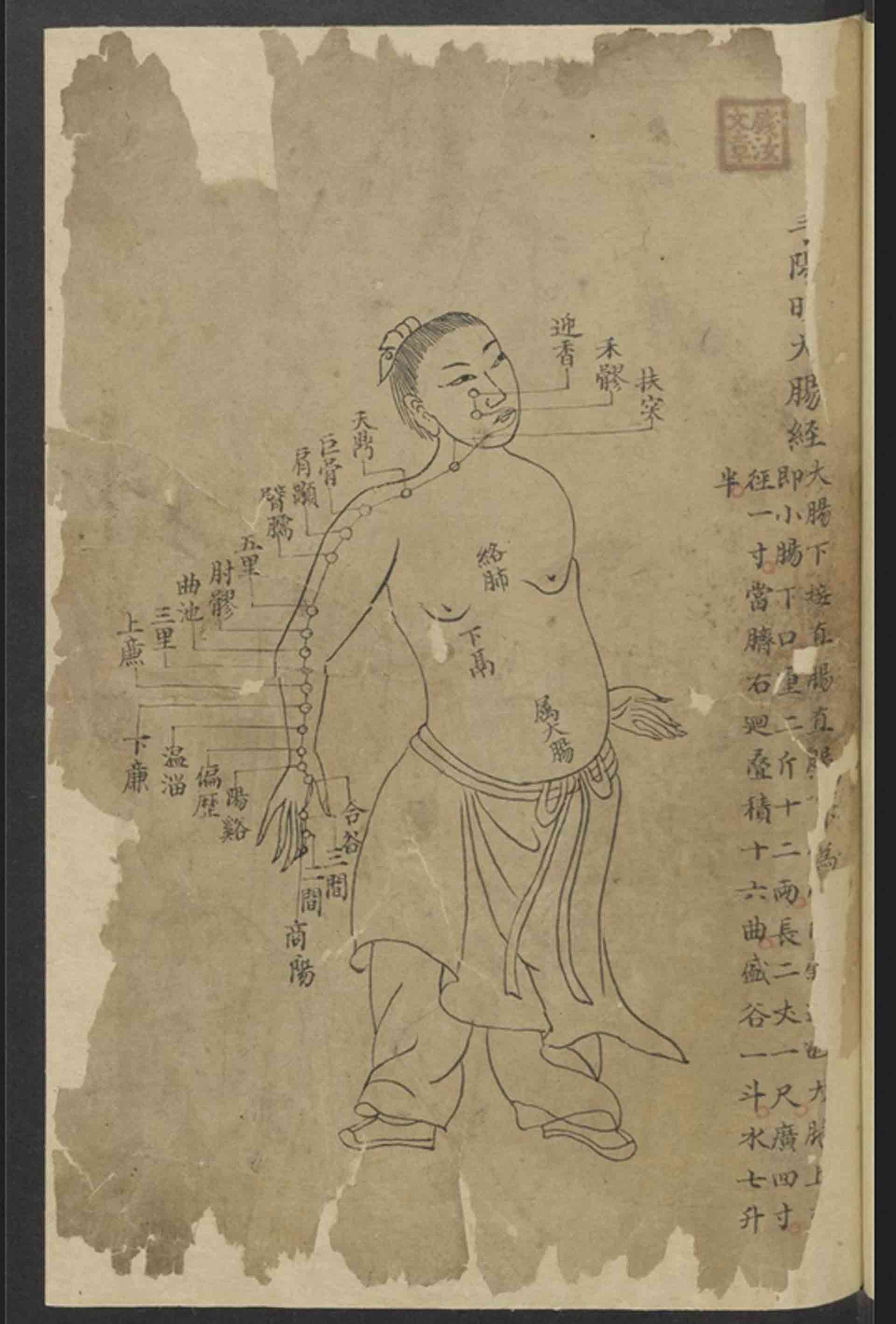

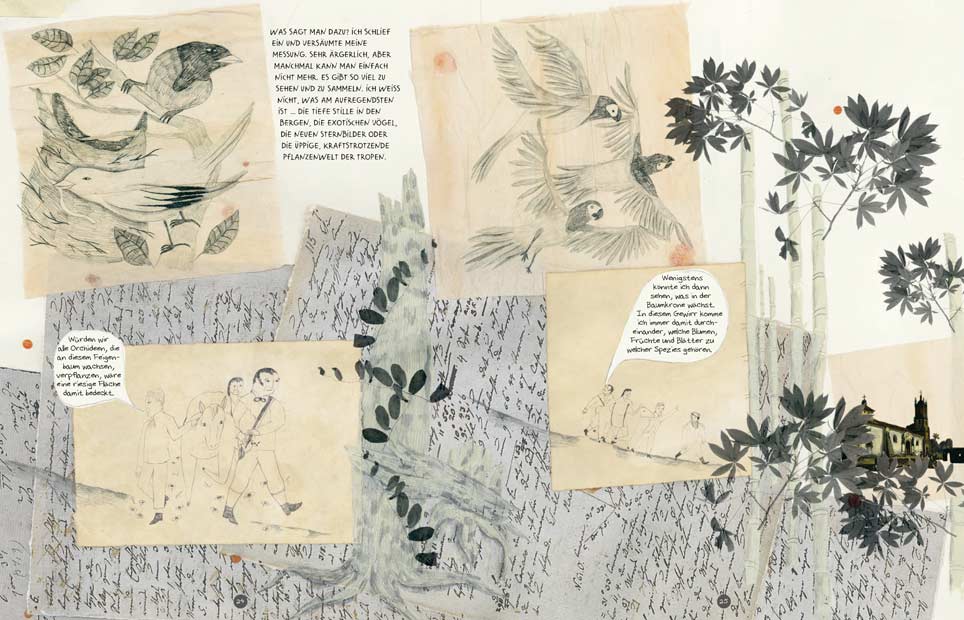

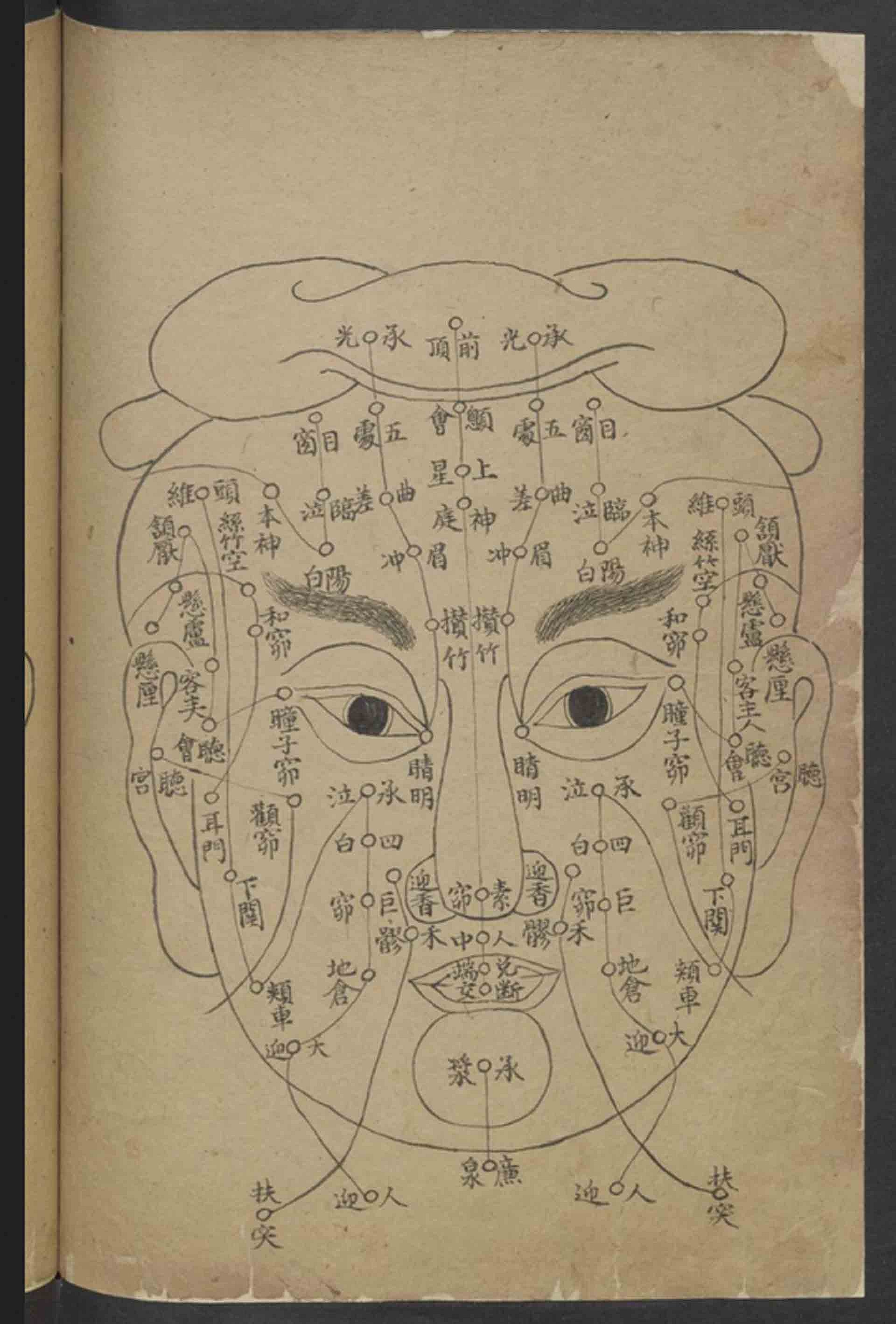

Illustration from Zhenjiu jingluo huichao 針灸經絡彙抄 ("Manuscript with Data and Pathways of Acupuncture"). The manuscript is part of a seven-volume work on acupuncture, external medicine, and medical prescriptions (late 19th/early 20th c.), Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Ostasienabteilung, Coll. Unschuld 8559

How did you come to work at SBB in Berlin? How was working with the colleagues there?

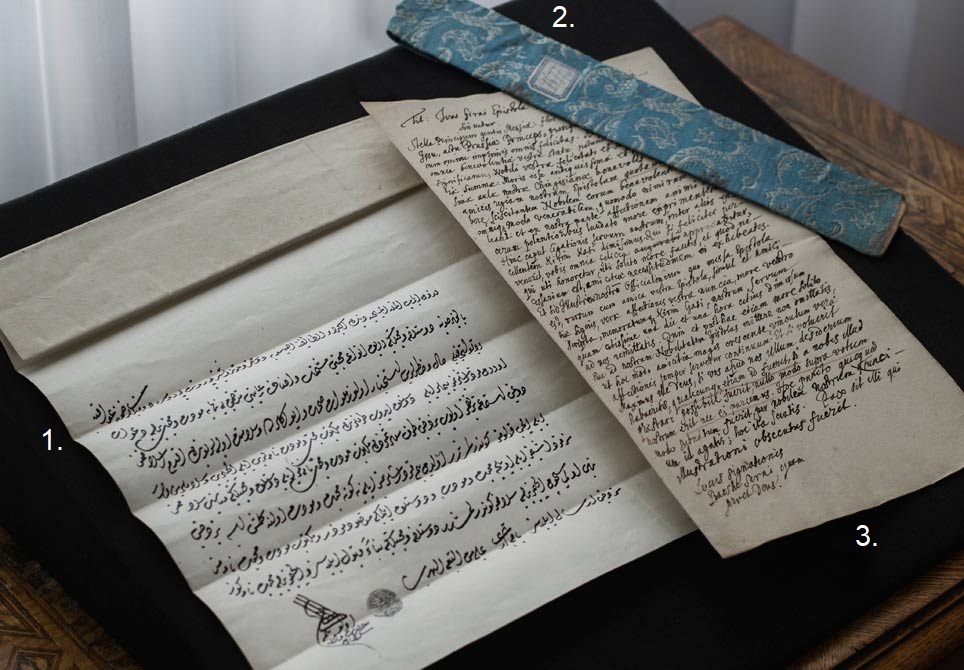

The collection of Chinese medical manuscripts held at the Staatsbibliothek is truly world-famous! It was donated by one of the original pioneers of historical research on Chinese medicine in the West, Paul Unschuld. It was always my dream to work with these manuscripts, so when travel difficulties getting to Asia persisted long into the pandemic, coming to Berlin was actually the next best thing for my research. Working at the Staatsbibliothek has been excellent – the staff is most kind and the collection is unparalleled.

Can you tell me about the Chinese Medical Manuscripts?

The entire collection is over 1,000 individual manuscripts, all of them handwritten. Most date from the 19th and 20th centuries, but many contain excerpts from older texts. Some of these excerpts are passages from canonical extant works, which is interesting because it demonstrates which parts of the canon ancient doctors found important. Still more interesting are unique manuscripts written by otherwise unknown physicians, because these demonstrate the multiplicity of practices of Chinese medicine that existed outside of the better known or more attested circles of very elite Scholar-Practitioners.

What can you do with the digitized manuscripts? What are user experiences?

An increasingly large percentage of the Unschuld manuscripts have been digitized, allowing them to be read and used by scholars everywhere. This is game changing, because you can do nearly everything with a digitized manuscript that you can with the original – reading through it, zoom in to analyze the handwriting, look for orthographic variants, added punctuation and other reader’s marks. Additionally, you can do these things without the cost and carbon footprint of travel, and without risking damage to very old, sometimes quite fragile pages. Several of the manuscripts I’ve reviewed in person were so damaged conservators had to rebuild and rebind them, and others bear the imprint of past damage by insects or water. The staff at the Staatsbibliothek is very skilled and has done excellent work to both preserve and digitize the collection!

That said, for those engaged in very close reading of specific manuscripts, it is always important to eventually spend time sitting with and reviewing the physical text if at all possible. One of my former teachers, Matthias Richter, argues in his monograph The Embodied Text (Brill, 2013) that scholars should not study manuscripts as if they were printed works in the received tradition, when we can learn so much from their physical attributes. This includes things like the paper type and size, style of binding, areas of wear from page turning or frequent past reference, marginalia, unusual orthographic conventions, calligraphic style itself, and notes added by later calligraphic hands. Thies Staack, another student of Richter, has applied this method to one of the Unschuld collection to very good effect, revising the dating and provenance of one very large manuscript in the collection. So although it is possible to do nearly everything with a digitized manuscript, in no way do I think this should supplant looking at manuscripts in person, if one is able.

How are they relevant for our times? Can the content be applied in practice?

Nowadays I think it unfortunately common to reify alternative medical traditions, conflating TCM (a modern standardization of acupuncture and herbal medicine prescription) with 2+ millennia of medical thinking and practice across not only China but also East Asia more broadly. Sinographic medical cultures --- by which I mean diverse traditions of medical practice in the places we today call China, Korea, Japan, Vietnam --- were never unitary even within specific regions, but instead practitioners were debating theories, dismissing “lesser” practitioners as quacks, writing books claiming the superiority of their own norms of practice, and sometimes forming traditions of their own with the help of dedicated students. There is something incredibly humanizing about this more diverse view of the past, because it allows for a view of ancient doctors who, not unlike allopathic physicians today, for the sake of their patient’s health engaged in empiricism as well as broad textual study. Ancient doctors actively worked to refine their praxis, honoring old through ways of knowing but engaging in contemporary study and debates. Manuscripts are a particularly good evidentiary source for this, because they demonstrate something about the levels of practice just below the elite levels that made it into the received corpus of printed medical texts. The ancient practitioners who copied passages from popular books, and less popular books, and sometimes elaborated their own ideas about the passages they copied out, took active roles in shaping medical knowledge that otherwise remains hidden from historical view. And cooler still, some texts record treatments or ideas that are not attested elsewhere, and thus may be from folk or oral healing traditions. Without this collection, we would have no idea certain remedies were ever used!

Have you gained any new insights during your work in Berlin?

My thinking about diversity in various levels of practice has become much fuller. Additionally I’ve gained a better appreciation for the need to move beyond talking about “Medicine in China” and towards more carefully situated, local studies; names for several medicinals or therapeutics are highly localized, demonstrating regional trends that are interesting, but easy to miss if you’re only looking at the big picture. For a long time we knew so little about Chinese medical history that we really needed big picture studies; now, I think enough of that frame has been developed that it’s time we start filling in smaller gaps – by region, by time period, by topic. Once we have more of this granular detail, then the big picture might come into new focus.

What is the most interesting find you have made?

It is so hard to choose just one! I do not know that this is my find, specifically, but one of the first manuscripts I looked at remains notable to me specifically because it is such an amazing text, but paradoxically, I have been able to find nothing about the author in any other source. It’s 7 volumes, all written out in a remarkably beautiful hand sometime in the late Qing dynasty, and covering a comprehensive range of medical topics – from acumoxa point location to herbal and food therapies to differential diagnosis and treatment of various diseases. The catalogue notes that it might have been intended as a textbook that never made it to print, and I agree. This comprehensiveness of scope is itself very intriguing to me because it feels so modern and ambitious, almost like a textbook.

Adding to this is that although much of actual text of these seven volumes was collected or copied from diverse extant sources, there is an original commentary, and the commentary is good! I was trained as a practitioner before I began my career as a historical researcher, so I know a few things about medical practice, and nearly every time something in the main text had me scratching my head – wondering about a specific term, practice, anything – the author helpfully offered a gloss of my question in the commentary! This leads me to think that if this was indeed a textbook, it was written not for pure beginners, but to help somewhat more advanced students level up from the basics.

Another thing I find fascinating but quite sad about this text is that although the author was clearly very educated, well versed in extant literature, and pedagogically savvy, I have not yet able to find any information about the copyist or presumed author. How many other doctors’ are entirely unknown to us? What other manuscripts like this might once have been written, but lost to what Stephen Owen calls the “flotsam and jetsam” of what texts have been able to survive the many metaphorical shipwrecks of historical upheavals intact?

What are plans for the future and next steps?

Ah, this is a hard question to ask a PhD candidate! In the upcoming year, I hope to have a more or less completed draft of my dissertation. Following graduation, who knows? I might win the lottery and find a teaching position, or, I might go back to clinical practice and research and write on the side. In my ideal vision I would actually find a post-doc that brings me back to Berlin, because of how much I have enjoyed my time here (yes, even through the famously dreary winter).