Hermann Parzinger and Michail Piotrowski on the future of German-Russian cooperation

Mr. Parzinger, for 15 years colleagues from German and Russian museums have carried on an intensive dialogue with the support of the Kulturstiftung der Länder (Cultural Foundation of the German States). What have you experienced?

Hermann Parzinger: The dialog started in 2005 with the purpose of creating a forum for intensifying cooperation. The starting point was the issue of war-related relocation of cultural assets. On the German side, it had become clear that policy making on this issue had ground to a halt. So we looked for opportunities to research and explore the respective collections in partnership with our Russian colleagues. The dialogue continued from this point. We succeeded in creating something that binds us together, when our difficult history should actually have separated us.

Projects currently being planned: Hermann Parzinger (left) and Michail Piotrowski have known each other for years. © Christoph Mack

As part of the dialogue, you not only investigated German collections. In 2012 the Volkswagen Foundation supported a research project on Russian museums’ losses during the war. Are there still any large gaps in the findings?

Michail Piotrowski: There are still many questions, even so many years after the war. It is not just a question of what was lost; it is mainly a question of what actually happened. The answers can teach us a lot for present times. Remember the evacuation of the antiquities collection from Palmyra. The evacuations in Germany and Russia could teach the best way to evacuate a museum in general. Ultimately, what matters is the art. There are moments when art is more important than the lives of people. I know that this is a provocative statement. But look at Notre Dame: people risked their lives there to save art. Now it is important to find out as much as possible about evacuation procedures during World War II. On the Russian side, there is little documentation from the beginning of the war. We have been combining German and Russian knowledge step by step.

Hermann Parzinger

Born in 1959, he studied prehistoric archeology and has been president of SPK since 2008. Parzinger is on numerous committees and councils and is a corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

We were able to turn a difficult history into something that connects us.

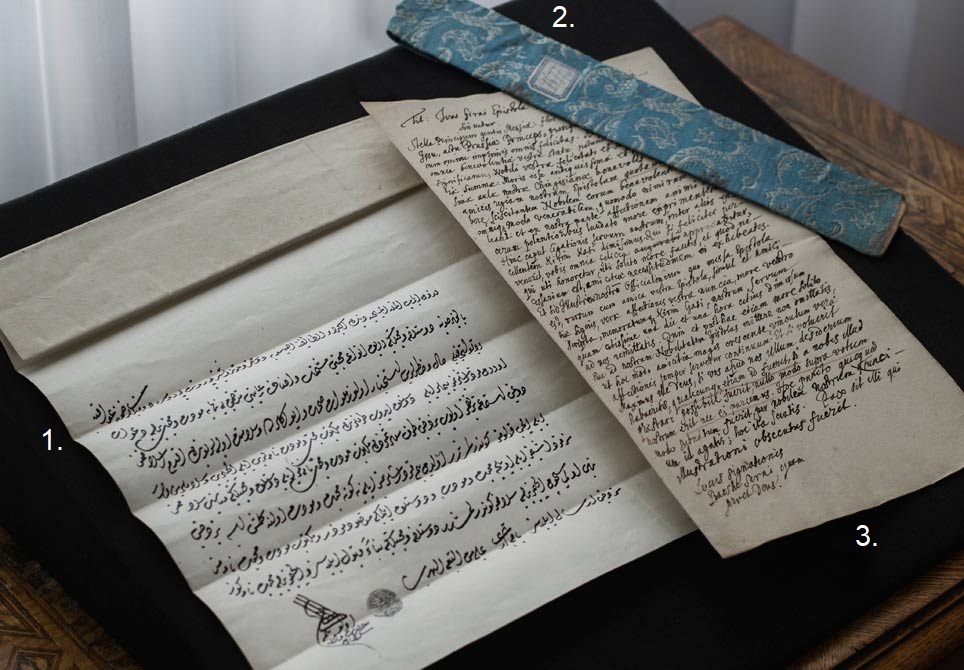

The story of the statue Victoria of Calvatone is part of this common history. For almost three years Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, SPK) and the Hermitage Museum have been collaborating closely to research and restore the statue despite all the political controversy regarding war-related relocation of cultural assets.

Parzinger: Restoring the Calvatone Victoria is a nice example of how well German and Russian museums work together. The project is naturally being directed by the Hermitage Museum, but our experts travel to St. Petersburg regularly to consult with Russian colleagues on the final appearance of the restoration. A lost work of art has been found and now we are caring for it together.

Will the Victoria be exhibited in the Hermitage Museum after it is restored?

Piotrowski: We will come to an agreement on this. An exhibition like this should definitely be held in conjunction with a scientific symposium. This is what we have always done in our joint exhibition and research projects. So the issue is not just exhibiting Victoria of Calvatone again.

What experience have you acquired from exhibitions in the past, including the ones on the Merovingians and the Bronze Age?

Parzinger: A great openness emerged from the exhibitions. Politicians also understood that candor among scientists does not preempt decisions; it is simply the basis of good cooperation. We currently have three other joint projects: an exhibition on the Iron Age, one on ancient vase painting, and one on Donatello. The latter is in cooperation with the Pushkin Museum, which now houses a large part of the Donatello works that used to be in the Bode Museum.

Piotrowski: Our cooperation started with an exhibition on Schliemann. It was the first time that objects went back and forth between Russia and Germany. Some people thought that was risky. Today we know that it was a good start. Based on this, we gradually developed a concept for further cooperation. So starting with Schliemann, we are now at Donatello. That is a good growth pattern. I think that we are setting an example for the entire world.

Parzinger: The point of our cooperation is shared heritage. Together, we are taking responsibility for objects that belong to all of mankind. After all, museums do not really own their works of art. We are curators. We preserve objects for the future and make them available in the present. As far as German-Russian cooperation is concerned, we can really be proud of what we have achieved. Today we work together more closely and productively than almost no other two countries in the world.

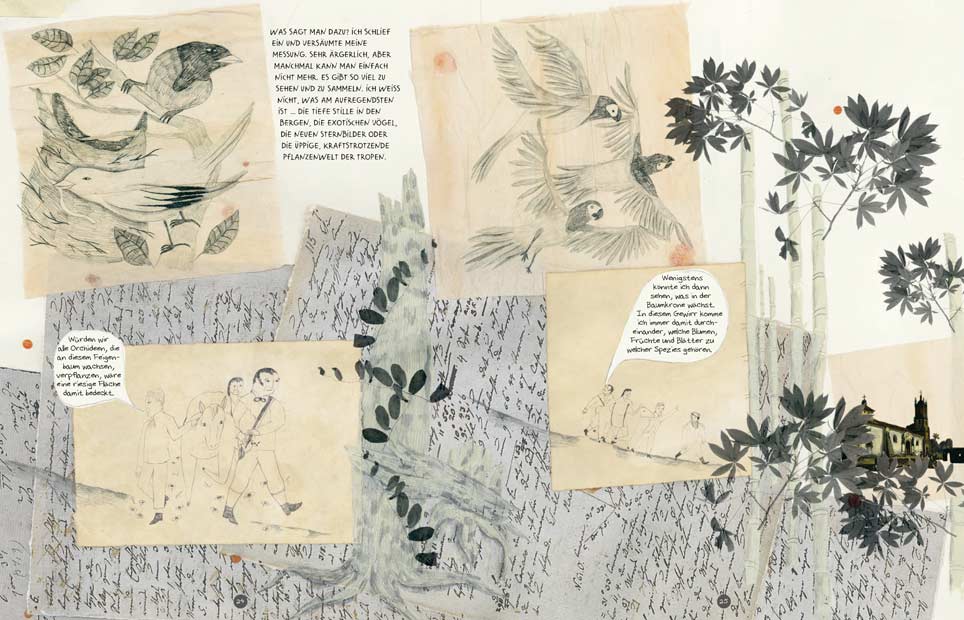

The book

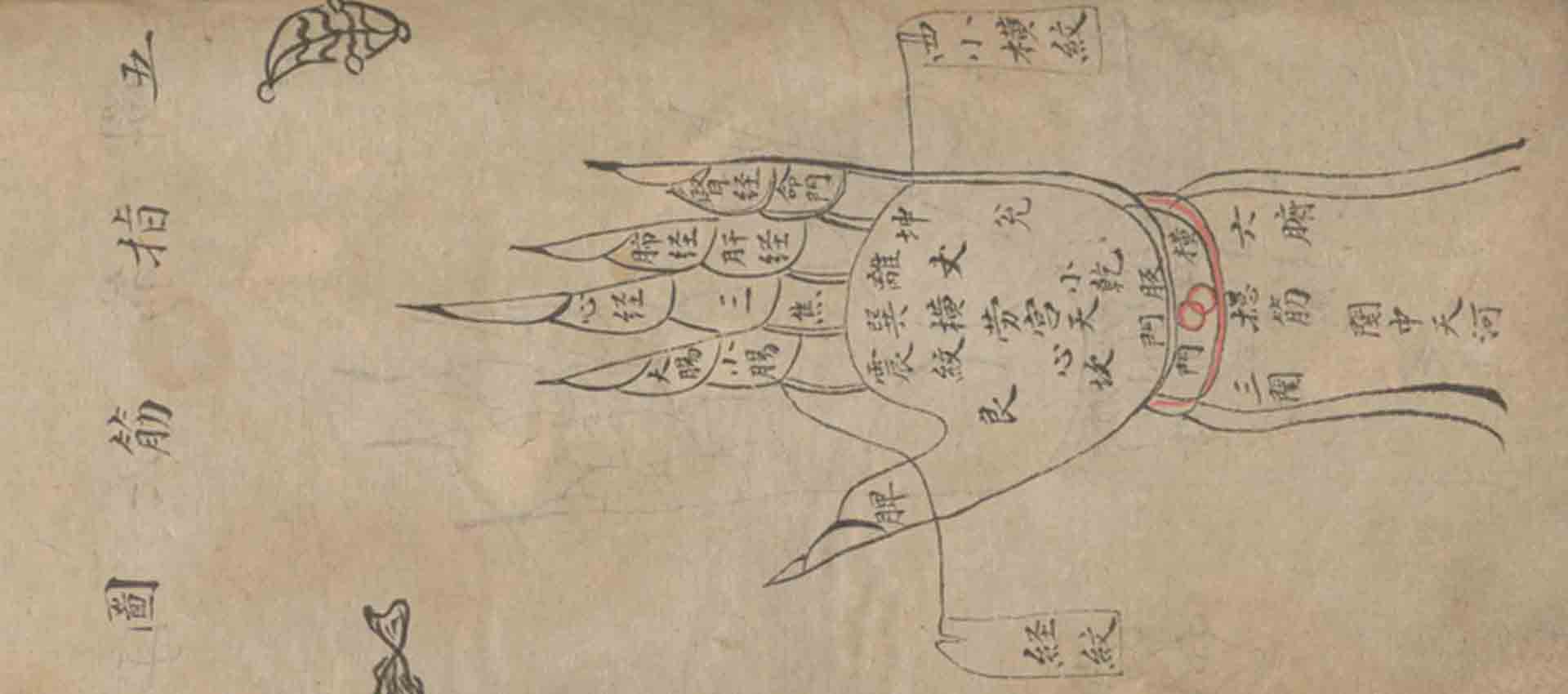

The Kulturstiftung der Länder and the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz are initiating a new series of publications containing studies on war-related relocation of cultural assets. The first volume, Raub und Rettung. Russische Museen im Zweiten Weltkrieg, which is about theft and rescue in Russian museums during World War II, is available now from Böhlau Verlag (45 Euros). Russian museums suffered great losses during World War II. Currently, research on the history of the museums and the fate of their collections is in its infancy. A project by German and Russian scientists attempts to close gaps in the research.