St. Matthew’s Church, the Neue Nationalgalerie, the Kunstbibliothek, the Kunstgewerbemuseum, the Philharmonie, and the Staatsbibliothek are carrying out a collaborative examination of the “Utopie Kulturforum” for the first time starting at the end of August.

The Berlin Kulturforum entered into history in 1960 as a utopia. It was a counterreaction born out of pain, and doomed by a vision. From the beginning a double-negation existed: the total demolition of the old buildings of the heavily damaged Tiergarten district along with the architectural relics of the Nazi regime on the one hand, and the repudiation of communist Germany beyond the Berlin Wall on the other. The desired metamorphosis of the place was not possible without hardship and loss. The clearing of the war ruins meant that the buildings, the history of the district and the fate of its occupants were obliterated and forgotten. Eradication and suppression were the leitmotifs in the process of dealing with the dystopia of Nazi city planning. The new beginning was to come about on a site freed of all rubble, memories, and ideologies. In the literal and figurative sense, a tabula rasa was created here.

Wasteland interlude. The desolate ruins of the Nazis’ House of Tourism. Otto Borutta, 100° Panorama, 1961–1962, © Berlinische Galerie, Repro: Anja Elisabeth Witte

“In opposition to the overwhelming desolation with its oppressive bleakness, Hans Scharoun together with free Berlin . . . has situated the Philharmonie at the farthest point that he dare, as confirmation of music as the purest sound of human community, and thus of faith in the power of freedom.” With these words, Adolf Arndt opened the Philharmonie on the Kulturforum in October, 1963 – three years following the reconstruction of St. Matthew’s Church, which from 1956 to 1960 stood in a wasteland, conceived as a monument and sign of life for the as yet unrealized site. The spectacular new architecture of the Philharmonie, without any right angles, axes, or architectural hierarchy, was a provocation to totalitarian regimes, and the strongest conceivable negation of the new buildings once envisioned by Speer for the Tiergarten quarter. These included the ruined House of Tourism, which was not demolished until after the Philharmonie had been completed.

In 1968, the Neue Nationalgalerie by Ludwig Mies von der Rohe followed as a reaffirmation of Berlin’s culture of modern architecture, which had been disrupted by forced emigration and war. Within this temple for the veneration of art, works by modern artists once proscribed by the Nazis were shown along with the most recent international developments in art from the United States and elsewhere, further perpetuating the narrative of the opposed political systems. The establishment of the two other new institutions at the Kulturforum was based on the historic precedents of the earlier Prussian State Library and the legendary Museumsinsel (Museum Island), which at this time lay in East Berlin.

Hans Scharoun arrived at an architecturally potent solution for his Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz (State Library of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation), which opened in 1978. He positioned it within the urban fabric as a bulwark against the East, at the same realizing a symbol of free, Western thinking in the interior with its highly functional reading room landscape.

An architectural competition was held in 1965–66 for the new buildings of the Museen der Europäischen Kunst (Museums of European Art). In spite of numerous futuristic design entries, such as that by Rolf Gutbrod, the diminished power of the post-war utopia was no longer enough to realize an outstanding architectural solution. Institutional pettiness, increasing bureaucratic intervention, and a multi-year planning moratorium led to a compromise solution. By 1985, when the Kunstgewerbemuseum (Museum of Decorative Arts) opened, Gutbrod’s ultramodern 1965 brutalism appeared to belong to another era. The change of architects and subsequent redesign did not bring about an improvement.

Following German reunification in 1990, the Kulturforum became a relic of the bygone era of West Berlin. The end of the clash of systems undermined the essential narrative that this place was a center of freedom for the art and culture of the West in the frontier city of the Cold War. Even today, the Kulturforum has not fully recovered from this loss of identity. Despite numerous urban design initiatives, competitions, and master plans, after sixty years it is still perceived by visitors as an unfinished, barren site with no inviting qualities.

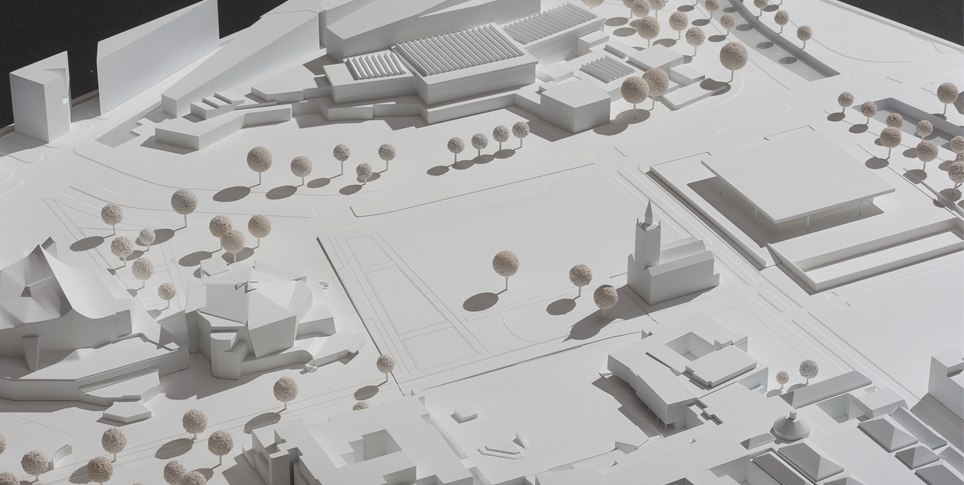

Since the 2016 competition for the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (Museum of the 20th Century) the Kulturforum has once again been in the public eye. Through its simplicity, the design by Herzog & de Meuron architects connects historic urban patterns with the ensemble of distinguished standalone buildings. The two central axes of the new building connect its neighbors and give the interior space a sense of place. The new construction will fill the void at the heart of the Kulturforum and alter people’s perception of it as a space.

Through the “Utopie Kulturforum” project, supported by the Hauptstadtkulturfond (Capital Cultural Fund), the institutions situated there are publicizing the history and potential of the Kulturforum jointly for the first time. With the program of dispersed exhibitions, public discussions, and art events, they also aim to sow the seeds of fruitful activity in future and to lay the foundations for closer collaboration.

Utopie Kulturforum

With the "Utopie Kulturforum" project, the institutions at the Kulturforum have come together for the first time to bring to light the history and the potential of the Kulturforum as a source of inspiration for the future. In the interview below, Joachim Brand, deputy director of the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library), explains exactly what is involved.