Research project on Tiergarten quarter: Joachim Brand, the deputy director of the Kunstbibliothek, envisions a vibrant celebration of the past

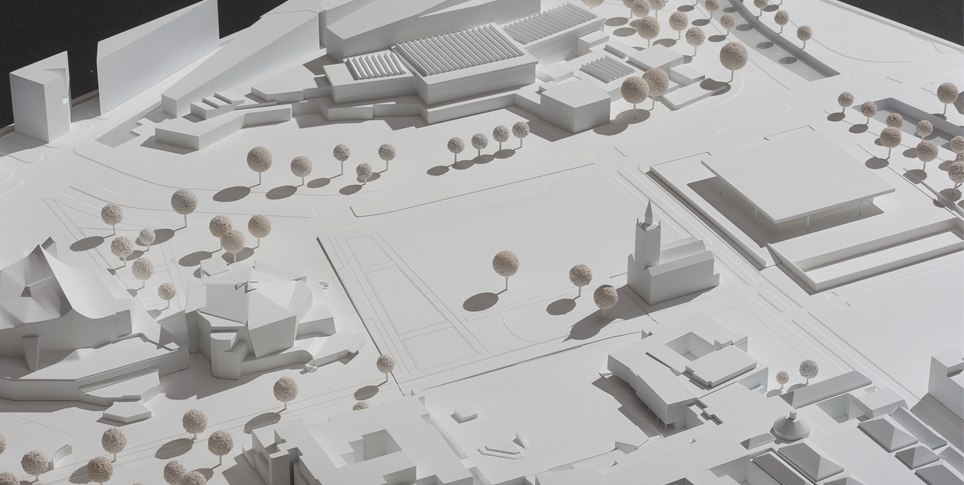

When Joachim Brand, the deputy director of the Kunstbibliothek (Art Library) looks out the large windows of his office at the Kulturforum, he is often reminded of what used to be here. He sees the Staatsbibliothek (Berlin State Library), the Berlin Philharmonic building and the construction site of the Museum des 20. Jahrhunderts (Museum of the 20th Century), and he knows that at one time, this neighborhood – the Tiergarten quarter – had magnificent mansions and urban villas, offices, cafés and hotels. Leading figures from the worlds of art and commerce resided here; it was a place where philanthropists, artists, intellectuals and bohemians lived side by side. Brand would like to keep the memory of that era alive: “What we need is a place where museum visitors and people passing through can learn more about the old Tiergarten quarter, its people and the dramatic events they experienced; where they can learn about the prominent Jewish art patrons who lived and worked here,” Brand says. “I would like to see a well-grounded, vibrant celebration of the past.”

View from the Landwehrkanal into Matthäikirchstraße. In the background the Church of St. Matthew. The Neue Nationalgalerie now stands on this part of the former Matthäikirchstraße. © Bildarchiv Foto Marburg/ Türck

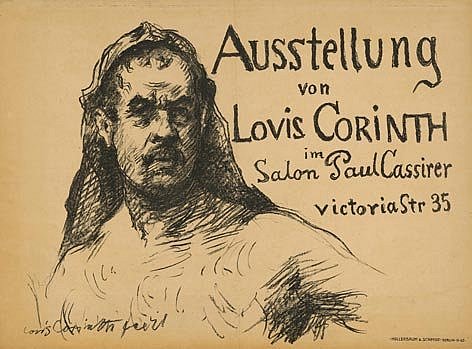

Brand has been working at the Kulturforum for more than twenty years, and the topic continues to occupy his thoughts. From the mid-19th century to the latter years of the Weimar Republic, the Tiergarten quarter was a place where modern art was created, collected and exhibited. Brand speaks with enthusiasm of the publisher and gallery owner Paul Cassirer, who ran his glamorous art salon right on the spot where the Philharmonie building stands today. He tells of Curt Glaser, a former director of the Kunstbibliothek who owned an important art collection and regularly invited prominent figures in the art world to meet for tea and liqueurs. Brand recalls the actress Tilla Durieux, the poet Else Lasker-Schüler and the publisher Ernst Rowohlt. James Simon, a generous art patron, also lived in the Tiergarten quarter, as did Johanna and Eduard Arnhold, art collectors who displayed works of Manet, Monet, Pissarro and Liebermann in their two-room gallery.

It was an Atlantis of modern art, Brand says, a world that the Nazis deliberately targeted for destruction and that was just as deliberately allowed to pass into oblivion after the war. “A silence surrounded it that was intentional and became entrenched,” Brand says. A clean sweep was made, both figuratively and literally, of the site that became the Kulturforum, he explains. The only remaining buildings of that time are St. Matthew's Church in the middle of the area, Villa Gontard in Stauffenbergstrasse (which now accommodates the head office of the Staatliche Museen) and Villa Parey, which has been integrated into the Gemäldegalerie.

How can the memory of the former Tiergarten quarter be kept alive on the basis of solid historical research? How could its residents be remembered and their stories told, including what became of them? How can the importance of the Tiergarten quarter as a center of modern art and literature be appropriately honored, here of all places, where the Kulturforum and its key institutions again serve as a home for the arts? In order to answer these questions, the Kunstbibliothek has now launched a research project with substantial support from the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media.

It has created a research position and has been accepting applications since February. The job will entail studying source material, examining building records to determine who owned what, and piecing together all the extant written and photographic sources in order to create a set of documentation that could later serve as the basis for an exhibition. “I would like to see a central memorial site at the Kulturforum. It could take the form of a visitor center, and there could also be a comprehensive presentation on the Internet, depending on which target group is being addressed,” says Brand.

He doesn't have to start from square one. Some steps have already been taken to commemorate the past at the Kulturforum. In 2021, for example, an information panel was put up in Sigismundstrasse, directly behind the Gemäldegalerie, to tell visitors about the history of the neighborhood and its distinguished residents. It includes a plan of the old street layout and a photo. Brand also mentions a number of plaques: a commemorative plaque for James Simon at the Representation of the State of Baden-Württemberg in Tiergartenstrasse, a plaque for Curt Glaser at the entrance of the Kunstbibliothek, and a memorial to the “euthanasia” murders behind the Philharmonie building. “But this is all very rudimentary, fragmentary,” he says. “We have to tie these pieces together conceptually and integrate them into a greater whole.”

Another commemorative effort cited by Brand is the Arnhold Initiative, an association of well-known art-lovers and professional historians. Their goal is to get the plaza in front of the Kulturforum renamed “Johanna und Eduard Arnhold Platz” and, if possible, to redesign the space in a way that evokes the garden of the Villa Massimo, the German Academy in Rome, which the Arnholds generously donated to the Prussian state. Brand also refers proudly to “Utopian Kulturforum,” a project in which all the institutions at the Kulturforum came together last year for the first time, in order to spotlight the history of the area with exhibitions, panel discussions and artistic events. The project made it abundantly clear that a great deal of work and research is still needed in order to really understand the significance of the location to the history of art and culture, and to commemorate the people who lived here.

The new research project is expected to incorporate the expertise of all the libraries, museums, cultural institutions and research centers at the Kulturforum. This effort will bring rewards on multiple levels, as Brand explains: “If we deal with the past and reconcile ourselves with it, we are better able to look to the future.” In the end, the project may succeed in accomplishing something quite apart from and beyond its strict academic objective: after so many years, the Kulturforum may finally find its identity.