The Kulturforum draws its strength from contradictions and contrasts. This gives the site a real-life, human quality.

Certainly, Berlin is no longer that truly mythical place. The late 1980s and early 1990s have long since passed, an era when every day a mad burst of creativity exploded like fireworks over the Spree. Back then, Berlin was unfinished, multi-faceted and open, a dizzying mix of history and the future, and seemingly everyone could participate in its transformation. Tempi passati. You can moan about it or accept it: Berlin has become conventional, even indistinguishable, as a result of the massive effects of globalization and financing on the city, which are felt not only by residents, but also experienced by visitors. Divided up, built up, and done up – that is how the German capital appears in 2021.

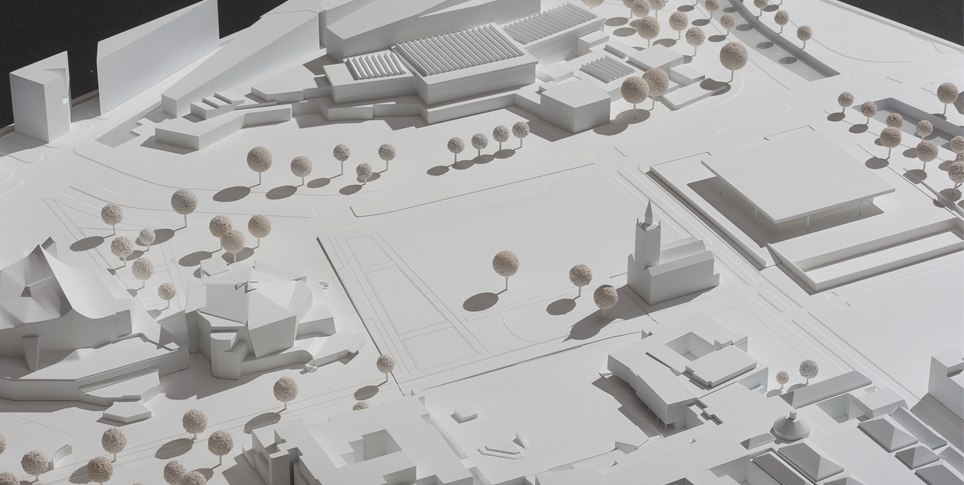

Thus it is all the more astonishing that in the middle of the city center one urban quarter has resisted this development: the Kulturforum. It is continually berated as notoriously incomplete, because the plans for its full realization disappeared into the city authorities’ plan chest for over forty years, without being carried out. Now, something will actually be built: a new museum for the art of the twentieth century. Designed by the Swiss architectural practice of Herzog & de Meuron, the building will join the ranks of such world-famous icons as the Philharmonie (1960–63, architect: Hans Scharoun), the Neue Nationalgalerie (1965–68, Ludwig Mies von der Rohe), and the Staatsbibliothek (1967–78, architect: Hans Scharoun in close collaboration with Edgar Wisniekwski). This shows how fortunate it was that the Kulturforum remained an “open,” even incomplete, example of urban Land Art. Otherwise, there wouldn’t have been space for a new building. And if you trust the genius loci of the place, which is indeed an unruly spirit, then there is no need to worry any further. Even after the construction work has been completed, the Kulturforum will doubtless remain a place of openness.

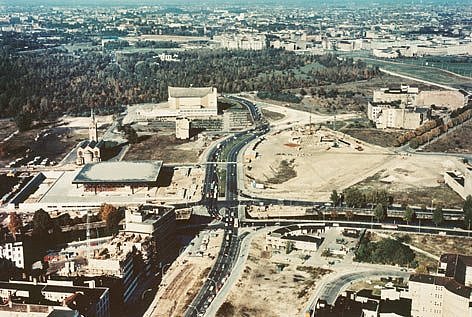

For one thing, the contradictions between various urban design concepts are baked into it. When the architect and urban designer Hans Scharoun developed a second Berlin cultural quarter between 1959 and 1964 as a counterpoint to the Museumsinsel (Museum Island), which was then in East Berlin, he envisioned a flowing, open urban space of parks, streets, and impressive large buildings. At least a part of this plan had been carried out by the end of the 1970s, but the street plan itself was soon reduced to wastepaper, including the urban freeway spur that would have continued behind the Staatsbibliothek (Berlin State Library). Even the spirit of the Tiergarten wasn’t really able to penetrate the Kulturforum; the buildings stand among asphalt and concrete, rather than among clumps of trees and swathes of grass.

And then there was the legendary “guesthouse.” It was to stand exactly on the spot where the museum designed by Herzog & de Meuron architects is taking shape. Accommodations for “artists in residence” were planned for this site. The curated artefacts in the surrounding buildings would thus be supplemented and enriched with contemporary works. This quarter, currently deserted at night, could have been populated, and perhaps even been made a lively place. In reality, it would also have resulted in more apartments, restaurants, and shops (a kind of expansion that is by no means out of fashion and is still very much possible.) However, the house for artists turned into an object of controversy for years. There were multiple attempts to realize it, and various plans and ideas for its design, until the whole project was filed away and ultimately forgotten.

Also abandoned in the early 1980s, along with the guest house, was the once-influential planning paradigm of the “urban landscape” (Stadtlandschaft). The post-war concept of breaking-up and restructuring the city was then passé. Nineteenth-century concepts of strongly defined blocks, buildings aligned with the street, and geometric public squares now informed a new urban design model dubbed the “European city.” At around this time, West Berlin incorporated a great deal of planning expertise via the International Building Exhibition. This was a period when the critique of modernism was institutionalized and the constructive, creative confrontation with the old dogmas opened up new paths, which have themselves become part of history in turn.

All of that naturally had to lead to a fundamental reshaping of the Kulturforum. The Kunstgewerbemuseum and the Kunstbibliothek (Museum of Decorative Arts, and the Art Library – 1979–85, architect: Rolf Gutbrod) were now complemented by the angular Gemäldegalerie (Old Master Paintings), an unfortunately rather feeble response to Venturi Scott Brown’s Sainsbury Wing for the National Gallery in London (1985–91). The Gemäldegalerie is not freestanding, but rather an elongated block that follows the street alignment (1986–98, architects: Hilmer & Sattler) and is scarcely recognizable as a building in its own right. Since then, Scharoun’s opening-up of the urban fabric has been answered with a blocky conglomeration surrounding the Piazzetta, the equally controversial ramp-like forecourt that conceals an underground car park.

Thus, the Kulturforum ultimately not only offers a haven for art in all its facets, but also acts as a kind of open-air museum showcasing various urban spatial concepts and their effects. Be it modernism or post-modernism, the urban landscape or strictly defined city blocks, they all face onto one another, intermesh, compete and debate, while mutually extending and complementing one another.

Unruly and Contradictory

If you wander around the Kulturforum with an open mind – ready to tolerate contradictions, acknowledge experiments, recognize a product of its time, and understand failure as a part of creative processes – then you will be richly rewarded. And if you really want to contemplate it further, by elevating the contrasts to a higher plane, and indulging in exercises of urban dialectics, then being there in person becomes even more rewarding. This would still be true even if it had only the two masterworks of late-modernist architecture: the Philharmonie and the Neue Nationalgalerie, which people journey to Berlin from all over the world to admire. Both are the work of one generation of grand masters (Scharoun lived from 1893 to 1972, Mies van der Rohe from 1886 to 1969), but they could scarcely be more different.

Scharoun’s concrete mountain range glows a golden-yellow and rises in waves as though the sound of the orchestra inside had caused the entire shell to vibrate. The interior aspires to be a continuous, flowing space, with a foyer reminiscent of lofty caverns, with meandering steps and passages, and finally the grandiose tent of the great hall with its tiers of seating, which quickens the heart and attunes the ear even before the first sound has rung out from the podium in the center of the building. And standing across from it, like a temple, is the cool, sublime hall of glass and steel – a work of absolute architecture, some say, a perfected artwork in itself, which tolerates no other purpose than to pay homage to itself (for this reason Mies van der Rohe relegated the exhibition spaces to the basement, as critics wryly observe). Two buildings, two poles: here, overt emotionality and playful form; there, apparent rationality and geometric rigor. Here, concealment of the building services, even a negation of formality and gravity. There, pure construction taken to the extreme, the most refined distillation of earnest, restrained architectural endeavor.

It is a fortunate act of providence that the other buildings of the Kulturforum don’t interfere in this clash of the titans, but rather take part in the scene like spectators at the ringside. That is certainly true of the Staatsbibliothek, whose elongated tanker-like form gives the entire site a tightly closed outer boundary, shielding the arena within. And it is precisely this embattled restraint that has allowed it to survive the generational leap from modernism to post-modernism.

Rolf Gutbrod’s range of buildings around the Piazzetta has an exterior material palette limited to red brick, in contrast to the older buildings. They appear calm, even introverted, keeping their qualities in reserve for the functional interiors of the library and of the exhibition and event spaces, not to mention the astonishingly long passages that lead directly into the Gemäldegalerie and its halls, which by contrast imitate the grace of nineteenth-century bourgeois exhibition salons.

A place of openness and a place of open contradictions: walking around the Kulturforum, it is impossible not to derive a moral for our times from this ensemble of buildings. For openness means tolerance – tolerance towards the other, the supposedly false, the allegedly half-baked. And in tolerance the factor of time plays an important role. There are echoes of the voices from over ten years ago that pleaded, in reaction to the demolition of the Palace of the Republic in favor of the Berlin Palace: please leave the space open. Open for the unknown, the inconceivable. Open for a coming generation. At the Kulturforum, one can study what openness really means: it produces disparity – truly part of life, truly human. Some may find this irritating. They may moan about the lack of perfection, or indignantly assert: “That’s just Berlin.” Others may call for a masterplan, for a “consistent” artwork, and the perfect form. But we can also simply be tolerant – and thus acquire the strength and equanimity to accept that even with the next museum masterwork, neither will the development of the Kulturforum be completed, nor the development of the once so glamorous city of Berlin.

Christian Welzbacher

Christian Welzbacher is an art historian born in 1970 who lives in Berlin. In addition to writing, he devises exhibitions and translates. He has received many prizes for his work, including the Theodor Fischer Prize of the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte (Central Institute for Art History) and the Kritiker-Förderpreis (Critics Award) of the Bundesarchitektenkammer (Federal Chamber of German Architects).