A few weeks before his death, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe recorded his memories on tape. They make for an extraordinary historical document.

Dirk Lohan, grandson of the famous architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, recorded his conversations with his grandfather on tape. They were special in several respects. For one thing, Mies was not confronted with stock questions – to which he increasingly responded with stock answers. And for another, these conversations took place only a few weeks before his death on August 17, 1969. The tapes were a record of what might be considered his last words and were later donated to the Museum of Modern Art as part of his bequest. Unfortunately, they went missing under unexplained circumstances. Only an incomplete typescript of the conversations has survived.

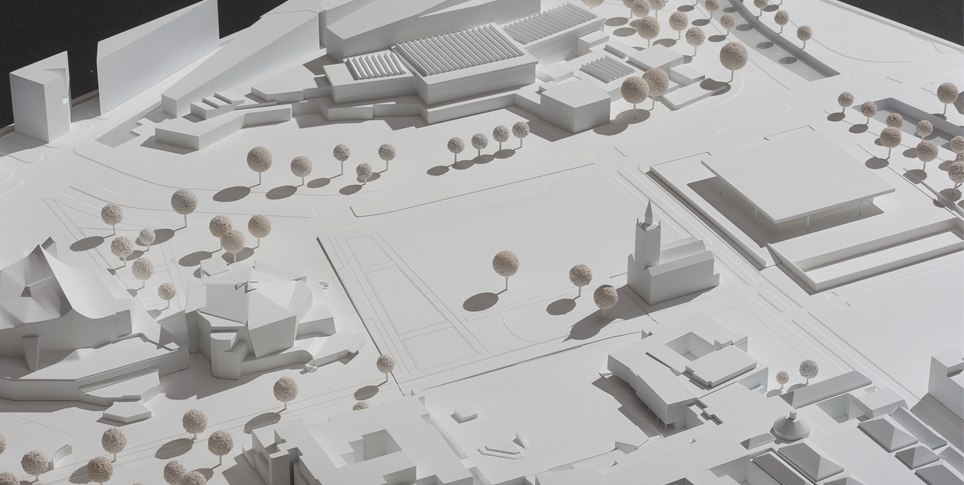

The Neue Nationalgalerie in the year 1968 © bpk/Nationalgalerie, SMB/Reinhard Friedrich

That 44-page transcript was recently published by DOM publishers, and it suggests that a real treasure was lost when the Mies tapes disappeared. In these conversations, which were not intended for the general public, Mies talks about his life more extensively and in greater detail than in any other known source. They contain an abundance of revealing and informative comments as well as touches of irony and humor, which he deployed with relish when articulating his reservations about other architects – in this case, Walter Gropius and Philip Johnson, in particular.

But perhaps the best thing about this source is that it clarifies certain aspects of the early work of Mies van der Rohe. We learn, for example, how important drawing was for Mies, especially drawing ornamentation and architectural details. He developed his talent for drawing in his parents' stonemasonry business, and it shaped the direction of his career. After a year of practical work at a construction company, he took a job as a draftsman of ornamental stucco before joining the office of Aachen architect Albert Schneiders in 1904. Schneiders had been engaged to build the Tietz department store, and Mies was assigned the job of creating drawings for the richly decorated facade.

In 1906, Mies moved to Berlin and took a job as a draftsman at the construction site office for the Neukölln town hall, where his work focused on the wooden paneling in the council chamber. His interest in learning to work with wood and design furniture led him to Bruno Paul. In the conversations with his grandson, Mies recalls an episode that illustrates just how important this was to him. It involved the construction of a small building for the tennis club in Berlin's Grunewald neighborhood. Bruno Paul had been commissioned to design it and he wanted to assign the job to Mies. Undoubtedly, it would have been a very respectable architectural assignment for him, but Mies turned it down because working with furniture was nearer to his heart at that time. So he persuaded a friend to apply to Bruno Paul as a stand-in, and Mies went as far as hastily preparing drawings for the application portfolio of his friend, which were then submitted to Bruno Paul under false pretenses.

The transcript also contains the only known evidence of another facet of the early work, an aspect that researchers had overlooked for a long time: Mies relates that during his days in Berlin, there was another Berlin architect who he admired very much, even more than Peter Behrens and Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Namely, Alfred Messel, who designed the famous Wertheim department store at Leipziger Platz. When he was employed at the construction site office for the Neukölln town hall, Mies would go to the city center on Sundays and look at Messel's buildings. He was especially impressed with the front façade of the department store, which faced Leipziger Platz. Mies not only compares Messel's proficiency with Gothic forms to Palladio's mastery of classical forms, he even compliments Messel, remarkably, on his ability to outdo Palladio in his details!

Traces of the influence of Alfred Messel can be seen in the first houses built by Mies, such as the Riehl House (1908) and the Urbig House (1915). Mies was especially fond of the Oppenheim country house that Messel built in 1906–07. In later years, he retained a vivid impression of Messel’s buildings. In the recordings of 1969, for example, he recalls two large stone volutes in the portal of a stable building belonging to the Eduard Simon House, which was built in Viktoriastraße (in the Tiergarten quarter) between 1902 and 1904 and was later destroyed in the war. As Mies had learned in the stuccowork business in Aachen, these were ornaments which, considering their size, you drew not from the wrist but from the shoulder. And Mies wonders what book might have a picture of these, in his view, marvelous and impeccably detailed stone volutes, so that he can show them to his grandson.