Philosopher Andreas Weber finds poetry in listening to trees and imagining the questions they might ask. Recently, he lent an ear to the old plane tree at Scharounplatz.

To learn something about the relationship between the modern age and the creative element, all you have to do is visit the Kulturforum in Berlin some day this spring. Crows are cawing in the gray air. And in front of the Philharmonie, a few kids are trying out their skateboards. The construction site for the Museum der Moderne (Museum of the 20th Century) is fenced in with galvanized wire mesh, pale like the city sky. In the northwest corner of the site stands a mighty plane tree, its branches laden with prickly seedballs. In the southern part of the plot are almost a dozen black locust trees, their crowns interspersed with round bunches of mistletoe.

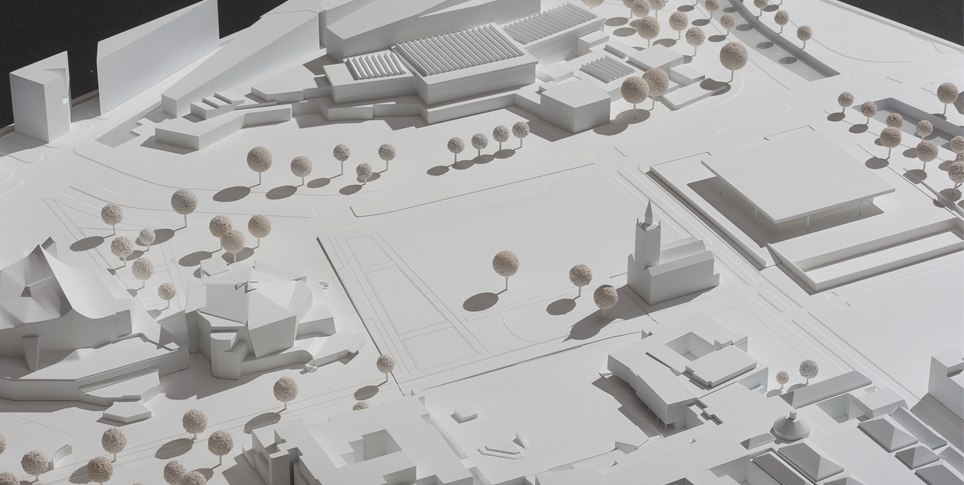

The 150-year-old London plane tree at Scharounplatz has survived all the events of Berlin's modern history © Christoph Mack

The site is still untouched by culture. It is practically a "non-place," an expanse of uneven asphalt with trees pushing their way up through it. In that respect, it is typical of Berlin: creative forces are carving out a path for themselves in unattended corners. Here, the creative forces are trees and shrubs, and they are doing what they have a knack for: growing, giving oxygen, spreading life. The old plane tree has been doing that for 150 years.

The tree is so important to the city planners that, in the design brief for the new building, they stipulated that it must be retained. It is a "natural monument," they wrote, and "its preservation is imperative." The winning architects therefore designed a huge rectangular cut-out in the even larger rectangular floor plan of the new building: a maximalist version of the niches otherwise created for figures of saints and other venerated objects. After all, the plane tree is a "natural monument." It is something worth exhibiting and it that can be integrated into the new cultural center and events venue with spectacular effect. The black locus trees with their mistletoe will be cut down.

Is the plane tree mega-niche the first artistic expression of an imminent sustainable society? Maybe even a cultural response to the crisis of climate change? Is the whole thing a marriage of art and nature, and therefore a new form of architecture for the Anthropocene? Is it greenwashing? Or simply sentimental?

The brief for the design competition also stipulated that, in the interior of the building, the architects should break down the customary separation between artworks and information about art – such as bookstores and libraries. The creative element will thus become part of daily life, and daily life will be infused with art. But like any beautiful thing, the tree, with which we inhale and exhale in concert, gets its own niche. Having long been an object of nature, it will now become an object of a museum.

Berliners are arguing about the new museum, as they must. But what does the tree think? If, as the competition brief proposes, the creative element should be intermixed with everyday life, then why is that which represents the epitome of the creative element right in front of us and inside us and above us, namely life, benignly enclosed in a recess – but not involved as a participant? Has anyone asked the trees in the asphalt what they want? What is good for them? Or, which amounts to the same thing: have we listened to what the trees are asking us?

Listening to what the trees are asking us could amount to a poetics, the seed of an artwork, something that might even be exhibited some day in the Museum der Moderne. As long as all of the trees – and not just the museum's plane tree – are still standing, in the fresh breeze, beneath the bunches of mistletoe, we can all do just that – go there and listen to the question they are asking us. And heed the response from within ourselves.

Andreas Weber

Philosopher, biosemiotician and journalist Andreas Weber argues for moving beyond the mechanistic interpretation of the phenomena of life. His debut book Alles fühlt brought Weber to the attention of a wide audience in 2007. In 2015, Matthes & Seitz published his essay Enlivenment. Versuch einer Poetik für das Anthropozän (Enlivenment. Toward a Poetics of the Anthropocene). Weber lives in Berlin and Italy.