The artworks from Hermann Göring’s country estate, Carinhall, still pose many riddles

On November 5, 1940, head Nazi ideologist Alfred Rosenberg received instructions from the top. Paris was occupied by the Wehrmacht, and the instructions described in detail the order in which the inventory of the Louvre was to be distributed: “1. The art objects whose future use the Führer has reserved the right to decide, 2. The art objects that will complete the Marshal of the Reich’s collections.”

Carinhall © Christoph Mack

The sender had no lack of self-confidence. It was Marshal Hermann Göring himself, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, in charge of the four-year-plan and as the “first in succession” at this time, in fact, the most powerful of Adolf Hitler’s paladins. Göring was a passionate and greedy collector, which made Carinhall, his luxurious country estate in the Schorfheide region, a private museum filled to the brim.

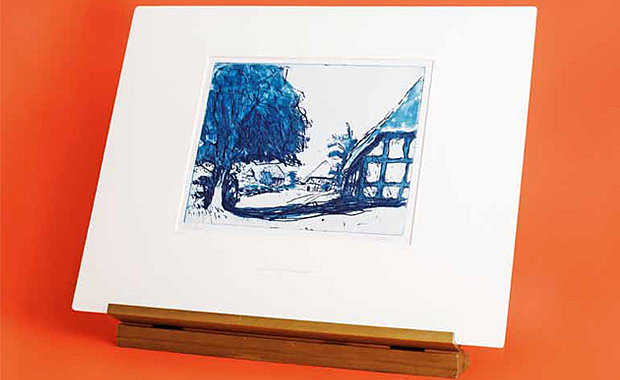

Archeologist Laura Puritani states: “Göring used his high-level political position to expand his collection with works of art that were confiscated from Jewish owners.” in Volume III of Dokumentation des Fremdbesitzes published by the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin – Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (National Museums in Berlin – Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation). After examining the inventory of the Nationalgalerie and the Gemäldegalerie for unlawfully acquired works in the first volumes, the third volume turned to the Antikensammlung (Collection of Classical Antiquities) and the antiques from Carinhall. Puritani examined 158 ancient artifacts in the Foundation’s inventory whose previous owners are not known, and 42 mainly fragmentary or restored antiquities that have been salvaged from Carinhall since 1946 and that are on permanent loan to the Antikensammlung from the Federal Republic of Germany.

“Fremdbesitz” (objects kept for someone else) is often a difficult matter for museums. These objects are kept safe in collections but are not owned by them. The previous owners are unknown, or the museum has lost contact with the owners for various reasons. Descendants often cannot be found. Or, to make it even more complicated, the objects could have been plundered from German collections by the victorious Allied troops and then returned to Berlin in 1958. But they cannot be clearly identified as part of the historic Berlin collections or inventories.

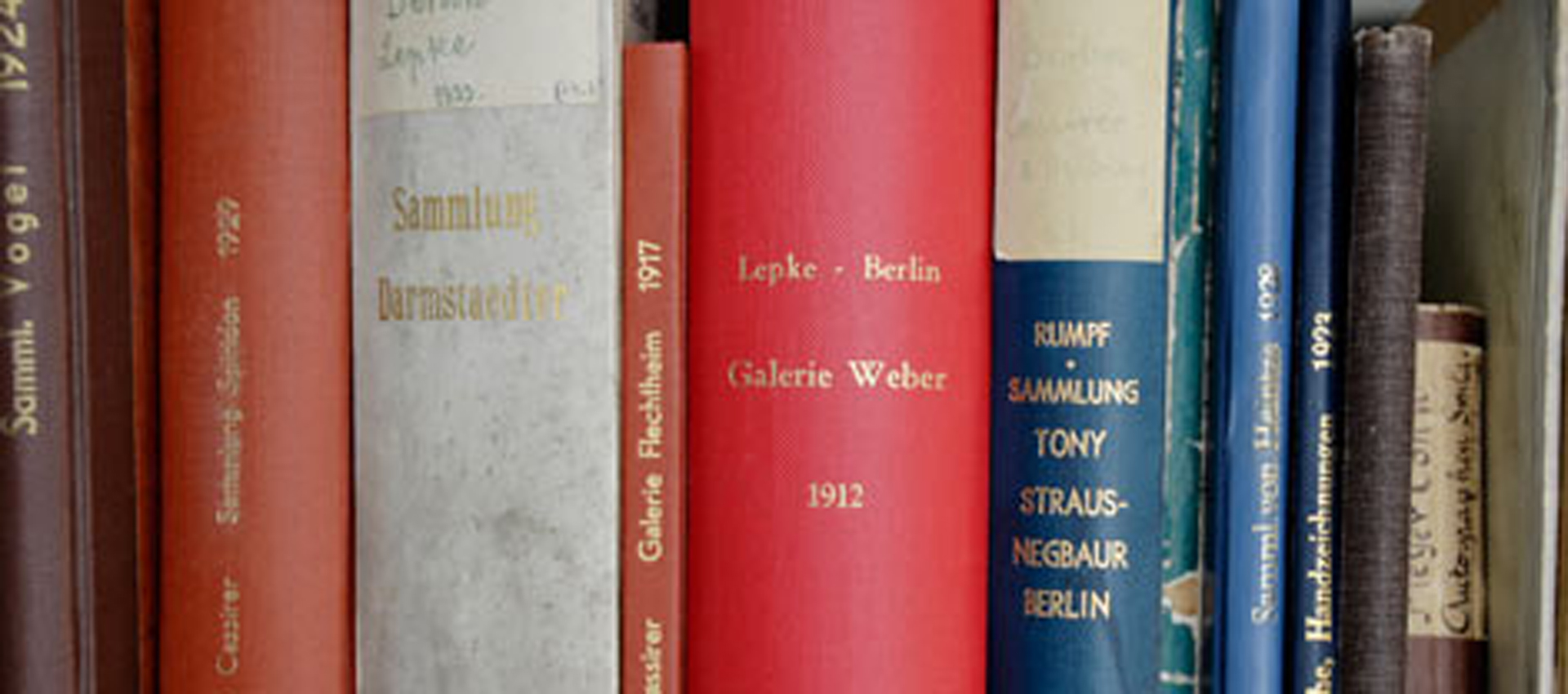

When Puritani started her project in 2013, she was faced with complex scientific detective work. First, she filtered a list of 300 antiquities from the 4,000 whose origins are not clear. Then she searched through archives, inventory lists, catalogs, files, correspondence and photographs for traces of the pieces that could lead to information on their origins and owners. The search even led her to US databases. She left the pieces from Carinhall, which are property of the Federal Republic of Germany, for last.

Puritani states that antiquities played “no special role” in Göring’s collection, but he probably thought that they suited his lifestyle. The archeologist reconstructed how he was able to acquire them based on the example of a third-century Roman sarcophagus. Göring’s agent, Walter Andreas Hofer, was commissioned to acquire it in 1942 for 120,000 lire – at that time about 45 times the average annual income. When the seller found out who the potential buyer was (Hofer carelessly used a letterhead with the title “Director of the Marshal of the Reich’s Art Collection”), he suddenly refused to sell. He was probably trying to drive up the price.

But Hofer was able to report proudly to Göring that “after days of negotiations,” he succeeded in buying the sarcophagus from the “thief” for the originally agreed price.

Tracing real objects with unknown owners is much more complicated. These include some that were confiscated in Berlin in 1945 by the Red Army’s trophy commissions and were sent to Moscow or Leningrad for storage. As a gesture to its socialist “brothers,” the Soviet Union returned about 1.5 million of these pieces, including works of art, archives and books, to the Staatliche Museen (National Museums) in East Berlin and the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen (National Art Collections) in Dresden, but they included objects that had never been part of the collections there.

Puritani painstakingly compared the Berlin inventories to the lists of objects prepared by the Russians. Sometimes inventory numbers that were still visible on the objects helped. But for some of the antiquities, the archeologist had to state that it was “conceivable, but not verifiable” that they belonged to the historic Berlin collections.

The small statue of a satyr is a curious case. Puritani found information that the bronze statue had been sent to Berlin “for safekeeping” towards the end of the war by the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Kassel (National Art Collections). But there is no explanation for the fact that the orgiastic woodland sprite was not picked up again after 1945 or why it cannot even be found in the inventories in Kassel.

Puritani found the legacy that the Bergungsamt beim Magistrat von Groß-Berlin (Magistrate of Greater Berlin Salvage Office) sent to the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin in 1947 especially challenging. Established at the request of sculptor Kurt Reutti, the office’s mission was to find and rescue ownerless art objects among Berlin’s ruins. Even though the individual finds were poorly documented, Puritani was able to disprove the hypothesis that the works from this office all originally came from Carinhall.

In a letter Reutti wrote in 1953, Puritani found a reference to “2 marble reliefs” that one of his co-workers had rescued from the cellar of H.W. Lange’s gutted art dealership. The reply mentioned that they had been put in the “National Gallery’s storage rooms.” In fact, the Staatliche Museen do have two reliefs in their inventory, each depicting a young man on a horse; on the back of each is a label with “Marble relief Reutti” written on it.

But Puritani could not reconstruct the chain of ownership any further. She said, “It is possible that the reliefs are part of confiscated Jewish property.” Cases like this link the subject of ownerless objects to the debate on restituting works that were confiscated from Jews during the Nazi regime. But the majority of the ownerless objects in the Staatliche Museen’s storerooms do not fall into this category. On the contrary. Like the satyr from Kassel shows, there are other possibilities.

Ultimately, the act of documenting the objects with unknown owners in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin offers museums and the public an opportunity to take a look at the identified objects. After all, the objects’ provenance might be able to be completed or the real owners might turn up.