An estimated 600,000 works of art were plundered by the Nazis. A summary of restitutions to date

Twenty years have passed since the Washington Conference on Holocaust Era Assets. This is an anniversary to celebrate even if the fact itself is no reason for joy. More than seven decades after the end of World War II, cases of people persecuted and robbed during the Third Reich still have not been cleared up completely. And there is no end to the process in sight.

The Washington Conference in December 1998 was organized by the US State Department and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Delegations from 44 countries, representatives of 13 NGOs, and numerous experts took part in the milestone meeting, which marked the birth of public interest in what was probably the largest art theft in history. But the breakthrough was not a complete surprise. The conference under the patronage of Madeleine Albright, who was secretary of state at that time, was well prepared. The resolution draft prepared by Stuart E. Eizenstat, the US undersecretary for economic, business and agricultural affairs, was based on an agreement between the Art Dealers Association of America and the American Association of Art Museum Directors. In its final form, it became the eleven Washington Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. A turning point in the treatment of stolen Jewish art in public museums, the resolution was the first international agreement after World War II. From then on, negotiations between the descendants of once-persecuted collectors and the museums that housed their possessions would be guided by the famous formula “fair and just.” This paved the way to restitution.

The conference focused on finding a way to return stolen paintings and works of art. The conflicts over the spectacular confiscation of two museum loans from Austria, two paintings by Egon Schiele, made this all the more urgent. Wally Neuzil, the portrait of Schiele’s lover, was confiscated from the Museum of Modern Art in New York after the descendants of the former owner claimed it. Schiele’s Wally made the lines of conflict clear: Who does art belong to? The original owners who had been dispossessed or robbed through a forced sale between 1933 and 1945? Or the current owners who had probably acquired the works without any previous knowledge about the criminal circumstances surrounding them? Until the fall of the Berlin Wall, private collectors and museum curators hardly gave a thought to the origins of the pictures, sculptures and art objects that had made their way into their collections during the Third Reich and afterward. A baffling case of suppression that is incomprehensible today.

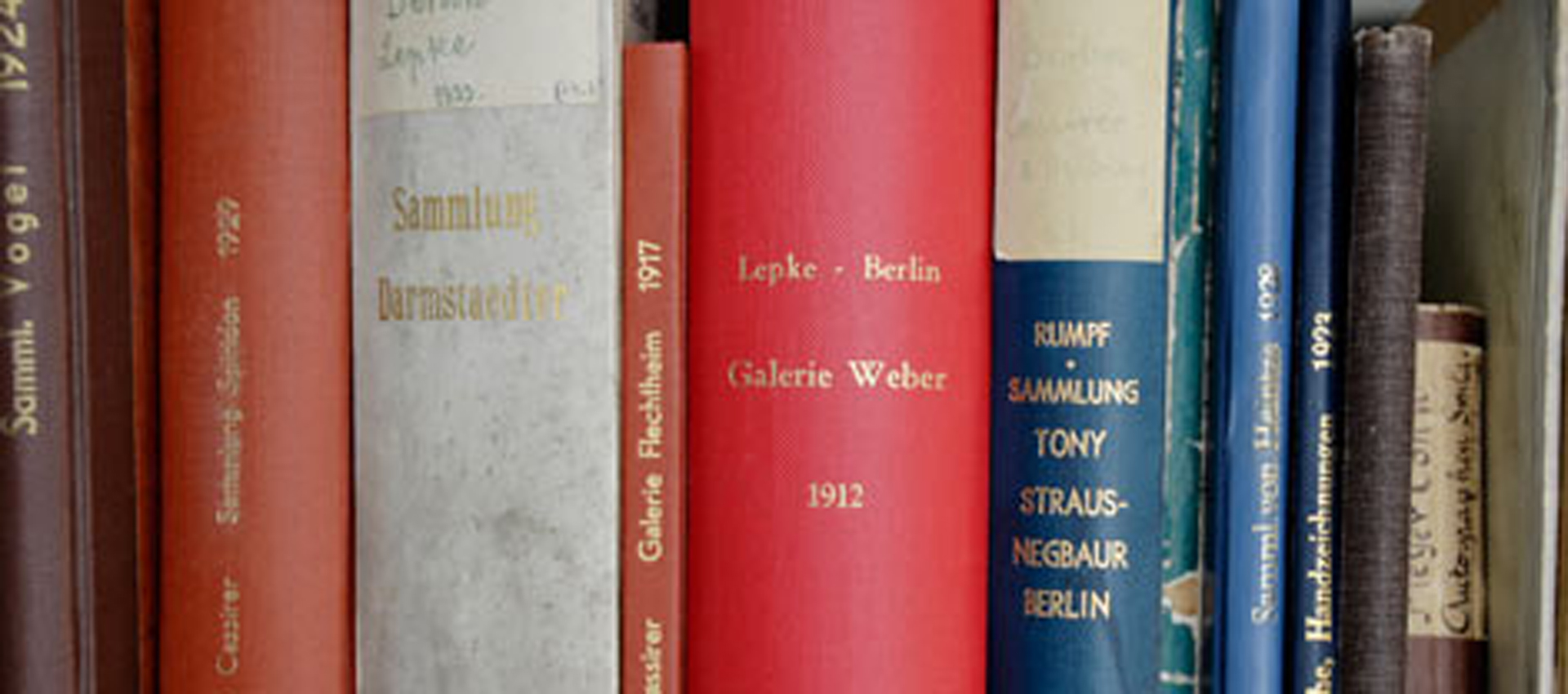

During the Nazi dictatorship, the government authorities created a legal basis for gaining possession of their victims’ property; their wealth, houses, land, art and books. They did this by gradually excluding Jews from all areas of society within the German Reich and, during World War II, in the occupied areas. To a large extent, this process of dispossession was gradual. Pressure was applied to art owners and they ultimately had to undersell their collections in order to support their families, pay for moving abroad or pay the government Reichsfluchtsteuer (Reich Flight Tax).The art trade profited from the goods that came into the market in this way. Their provenance was covered up–sometimes more, sometimes less–and that made it all the more difficult to reconstruct the sales channels decades later.

According to estimates, 600,000 works of art turned into Nazi plunder between 1933 and 1945, half of them in Eastern Europe. Tens of thousands of them are still in public collections or private ownership. The Washington Principles were the first international regulations for dealing with these “last prisoners of war,” as Ronald Lauder, the chairman of the Commission for Art Recovery of the World Jewish Congress, once called them.

Because it had been confiscated from museums after 1937 and then either destroyed or sold, modern art, termed “degenerate art” by the NS government, was not covered by the principles. In its case, the government had stolen from itself. The legal basis was not changed after 1945, so the government could not prosecute the new owners and ownership could not be reversed.

Public attention did not turn to Nazi art theft again until the Berlin Wall fell, and previously inaccessible archives could be opened. For many years, the victims themselves did not ask what had happened to the objects. In the first years after the war, many Holocaust survivors were preoccupied with rebuilding their lives. Others could not or would not reduce the tragedy to the material level, as Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Elie Wiesel explained in his opening speech to the Washington Conference. Subsequent generations would have the task of formulating their just demands more clearly. And the next generation was willing to face the problem again.

In West Germany, the deadlines for restitution expired in 1958 and 1969. At that time, the focus was on returning real estate and wealth. The subject soon became old news. In East Germany, on the other hand, only loyal followers of the system could have their claims honored. The fall of the Iron Curtain and the adoption of one of the GDR government’s last laws on property into German federal law created the conditions for a new approach. But first the provenance of real estate that was previously dispossessed or sold under duress had to be dealt before the focus could be turned to its contents–including art.

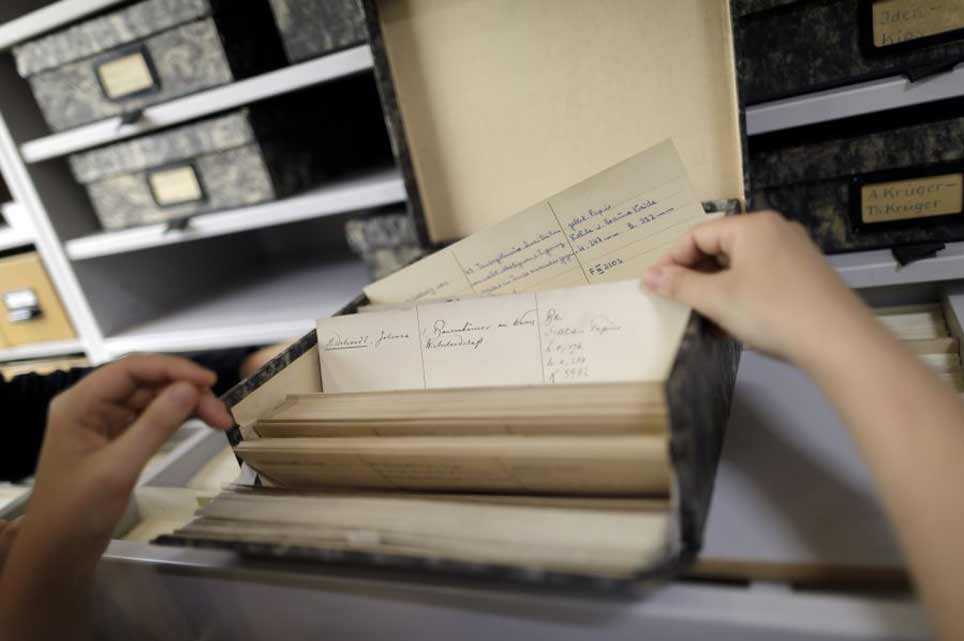

The Washington Conference provided the basis for how to proceed. The eleven principles that were adopted to handle “cultural property confiscated as part of Nazi persecution”–not just in Germany but in all of Europe–were not laws. Instead, they represented a commitment. In particular, the eighth principle lent them significance: “If the pre-War owners … or their heirs, can be identified, steps should be taken expeditiously to achieve a just and fair solution.” A year later in 1999, the German federal government followed up with a “Joint Declaration” with the German states and umbrella organizations, which is based on the Washington Principles, and in 2001 with the “Handreichung zur Umsetzung der Washingtoner Erklärung” (Guide to Implementation of the Washington Principles). It called on all museums, libraries and archives to search their inventory and restitute where necessary.

At the tenth anniversary of the Washington Conference, Bernd Neumann, the German minister of state for culture at that time, stated: “There is no statute of limitations on moral responsibility.” In 2008, he inaugurated a special program for provenance research, which was expanded by his successor Monika Grütters and again after the scandal surrounding the 2012 “Munich artworks discovery.” In 2015, Deutsches Zentrum Kulturgutverluste (the German Lost Art Foundation), headquartered in Magdeburg, was founded to coordinate the research. Today, provenance research is a core task for museums. The Washington Conference laid the cornerstone for this process of raising awareness.