In the restitution debate there is a gap between justice and morality. Our author calls for reevaluation.

Is identifying and restituting art plundered by the Nazis a question of justice? The answer to this question seems obvious, but it is interesting that this clarity doesn’t have anything to do with the actual answer. Of course, you could argue that justice can only be served if the victims of NS robbery and plunder and the heirs of the murder victims actually get back what was stolen from them. But you could also object: There can be no justice for the murder of six million Jews. It will not be served by paying money to all victims and their descendants, nor by restituting art to individual victims and their heirs. Referring to restitution of NS plunder, Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel said: “Even if – as a gesture of restitution or an act of contrition – we received all the money in the world, it would not relieve the pain that we feel at the thought of just one murdered child in Birkenau.”

In the art restitution effort, great expectations have only been matched by the ambivalent experience of applying them. Exactly in view of the expectation that justice will be restored by returning the art, restitution fails in a very elementary point: restitution cannot turn back time. Just circumstances under which National Socialism did not persecute specific groups of people cannot be reconstructed. Rather, restitution can only be an instrument of a conscious and active process of reparation, designed to react to injustices that were committed; it can be a source of satisfaction for the victims and their descendants, and an act of contrition for the perpetrators and their descendants.

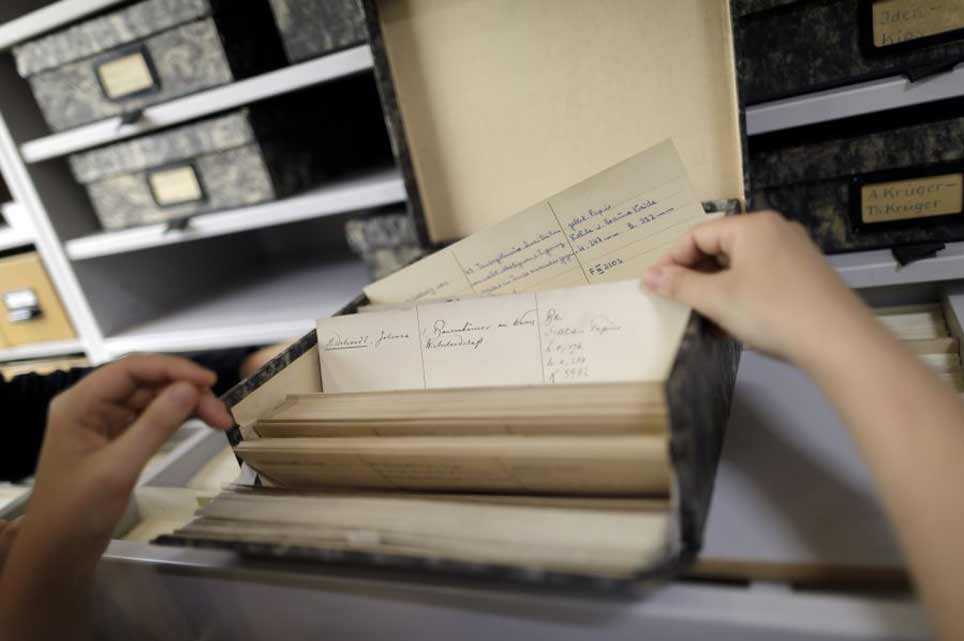

Exactly because restitution is only conceivable as an active effort of reparation, it cannot constitute a judicial or anthropological universal. On the contrary, when the Allies created a legal basis for the restitution of the assets that were plundered and extorted from the victims of Nazi persecution in the western German occupation zones after World War II, it was a historically unique occurrence. For that very reason, the new laws were formulated carefully and aimed at compromise. While persecuted people were promised complete restitution, they had very short application deadlines after the end of the war. If they missed the deadline, all further claims were excluded. By today’s standards these regulations may seem insufficient. By the standards of that time, they were revolutionary. After German reunification, they were also applied to subsequent reparations in the new German states and the deadlines were just as strict.

The legal situation remains the same. When Germany signed the Washington Declaration in 1998, professing on the international level to want to find “fair and just solutions” for unrestituted Nazi stolen art, the country deliberately decided not to substantiate its declaration of intent with new, legally applicable claims for Nazi victims and their heirs. Despite all pleas of special historic responsibility, victims of NS persecution and their heirs are supplicants when it comes to questions of restitution. They can call for the return of the stolen art works supported by moral arguments, but generally they are not entitled to restitution. Moral claim and legal reality are as far apart as possible.

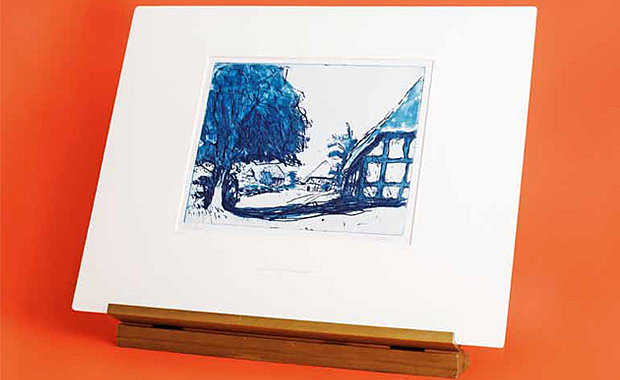

In practice, the fact that Germany has not adapted its laws to satisfy established moral expectations has led more and more heirs of Nazi victims to turn to US courts when making their claims for art restitution in Germany. In this way, restitution is no longer considered an element of the German policy of reparation. Instead, from the claimant’s point of view, it is a legal issue that needs to be enforced on the international level in the face of German resistance. Moral grounds are supposed to be above legal regulations in the German application of the Washington Principles, and under the circumstances pleading them becomes more than dubious if the claimants are not willing to be content with a moral solution and instead demand a legally binding decision.

This basic conflict can only be resolved if the Bundestag, Germany’s parliament, decides to adopt new legislation on restitution claims and provide claimants with truly applicable legal positions instead of mere moral expectations. In this way, the Bundestag would explicitly take responsibility for National Socialist injustice and act to contribute to restitution. Of course, this would not relieve the pain we feel at the thought of one murdered child in Birkenau. But it could keep the memory of these children’s fate alive.

Sophie Schönberger

Sophie Schönberger holds the chair for constitutional and administrative law, media law, art and cultural law at the University of Constance. She previously studied the mathematics of technology and business in Berlin, and from 2000 to 2005 she studied jurisprudence in Berlin, Rome and Paris. After her second state exam, she worked at the University of Bayreuth and Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, where she received her professorship.