The architect of the Washington Conference, Ambassador Stuart E. Eizenstat, on the achievements of the Washington Principles from 1998.

How did you first become involved in the issue of Holocaust-era assets?

In 1968 I joined Vice President (Hubert) Humphrey’s presidential campaign against Richard Nixon, as his research director. One of my colleagues, Arthur Morse, had just published a book called While Six Million Died. It directly implicated (President Franklin) Roosevelt’s administration, up to and including the president, in knowledge of the unfolding Holocaust and relative inaction and lack of urgency in dealing with it. Because Roosevelt had been an iconic figure in my household when I grew up, I found it a complete shock. I pledged to myself then – I was all of 25 years old – that if I ever had an opportunity in the U.S. government to remove this cloud from the otherwise stellar record of the U.S. and President Roosevelt during the war, then I would take it.

You became the U.S. ambassador to the EU in 1993 and worked to help Jewish and other religious communities in eastern Europe to rebuild their infrastructure – schools, synagogues, churches, community centres. And then you negotiated settlements for claimants of dormant Swiss bank accounts and victims of Nazi slave labour. How did this lead to art?

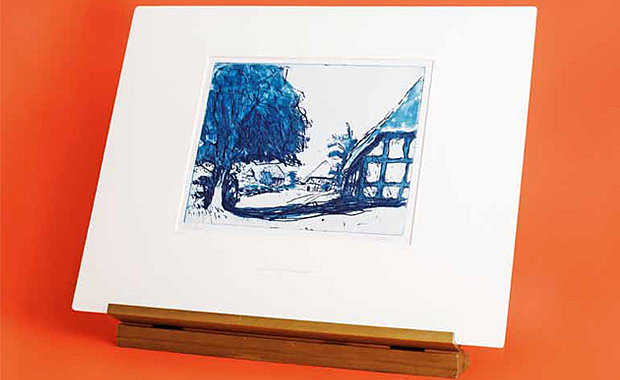

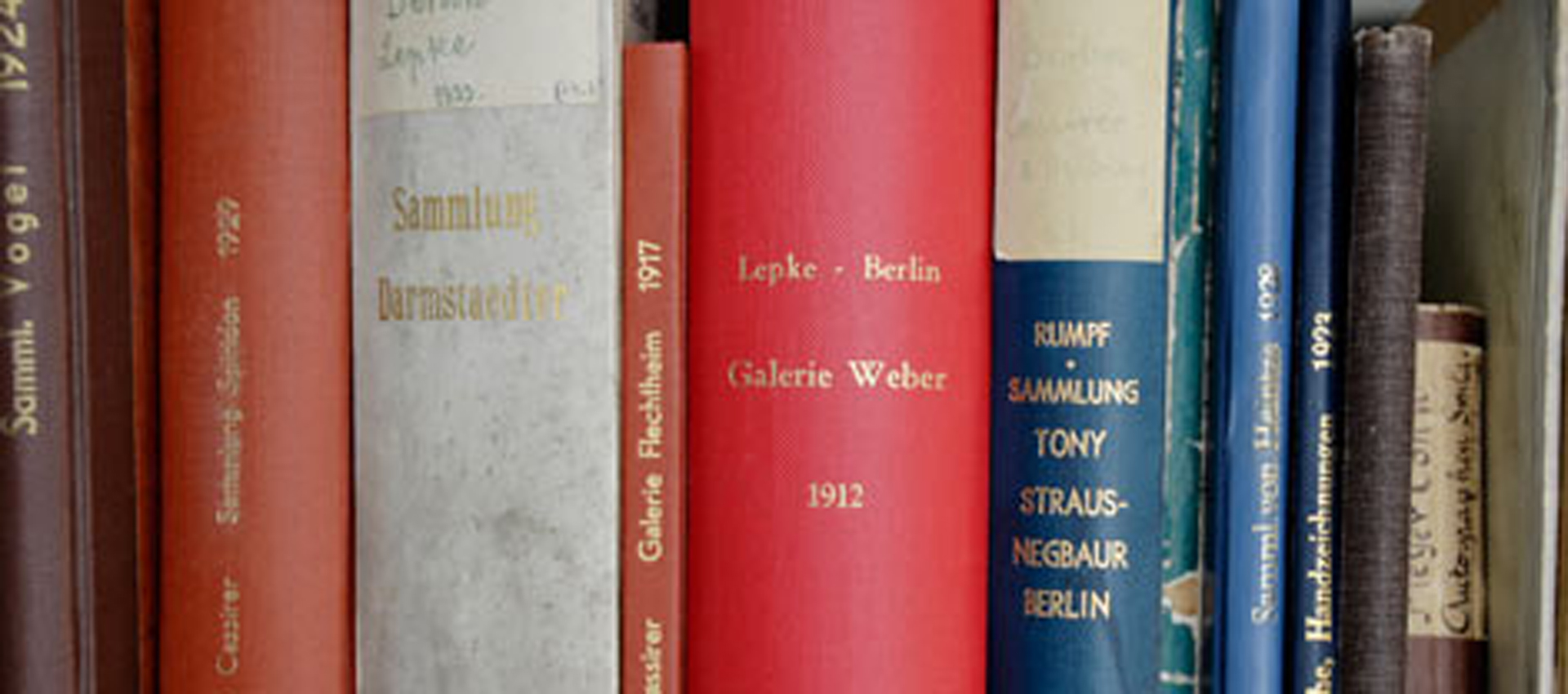

Several scholars – Lynn Nicholas, Jonathan Petropoulos, and Hector Feliciano had published books about Nazi-looted art. There was a conference hosted by Bard College in New York at which they presented their shocking findings. It all came to light shortly before the London Conference on Nazi Gold. I asked the British to put art on the agenda. I said at this concluding session that the issue of Nazi-looted art was so dramatic, little recognized, and important – the experts were saying some 600,000 paintings had been stolen by the Nazis – that it was worthy of a full conference. So I invited over 40 countries to a conference in Washington in November/ December 1998 to focus on Nazi-looted art and cultural property. That resulted in the Washington Principles on Nazi-looted art, which I negotiated along with my excellent assistant and career diplomat, J.D. Bindenagel.

Do you have any regrets about the principles being non-binding?

I have no regrets because it was the only way to get it done. At the closing conference, a very important statement was made by Philippe de Montebello, who was then the long-time head of the Metropolitan Museum. He said the art world will never be the same -- that this had revolutionised the art world.

What have been the major achievements of the Washington Principles?

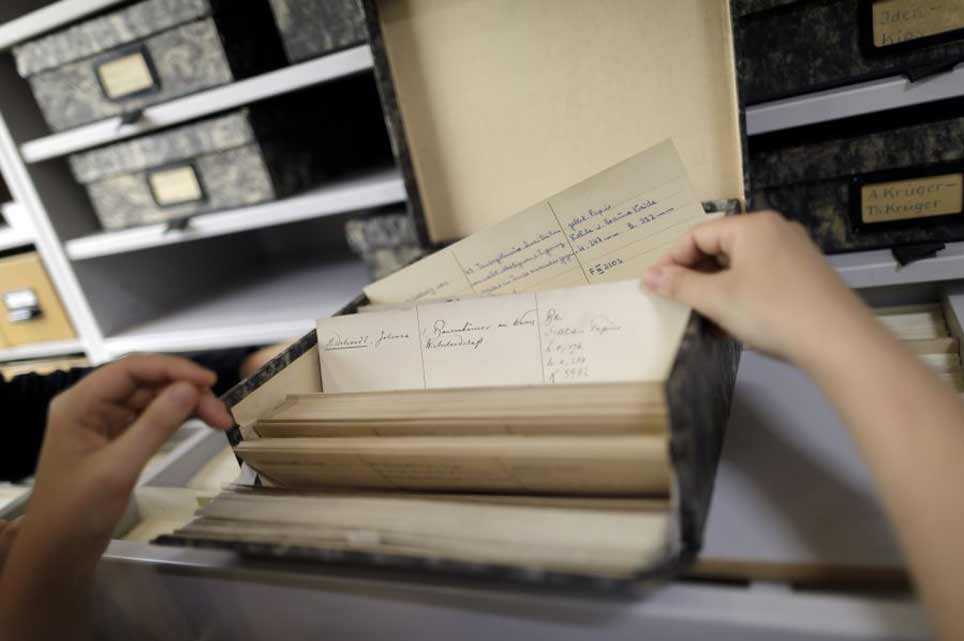

A number of things have happened. Both Christie’s and Sotheby’s, the two largest auction houses, have full-time staff (led by Monica Dugot at Christie’s and Lucian Simmons of Sotheby’s) devoted to provenance research. Monica Dugot at Christie’s has told me that they refuse to sell up to a dozen pieces a year. They cannot always be returned to claimants, because the company has a fiduciary duty to its consignors, but at least they cannot be sold through that channel. Second, hundreds of pieces of Nazi-looted art have been returned to their rightful owners, or compensation has been paid. Third, we knew there would be a burden on families in trying to trace their art back to that period. So the American museums, which are all private with the exception of the National Gallery in Washington, set up a search engine that permits a potential claimant to submit their claim, which then goes to about 100 museums. Fourth, the Netherlands, the U.K., Austria and Germany have set up claims processes outside the court system to facilitate the resolution of Nazi-looted claims.

How do you assess Germany’s progress since 1998?

Germany made a good-faith effort, but frankly it has not been implemented well. The commission works very slowly, very few claims are permitted, and there is a need for accelerating its efforts. Having said that, (Commissioner of Culture) Monika Grütters deserves a lot of credit. I went to see her a few years ago and she told me she had just gotten an additional €4 million from (Finance) Minister (Wolfgang) Schäuble to give to German art museums to accelerate and deepen their provenance research and publish their results, which is the first critical step to try to provide justice to claimants whose artworks were confiscated by the Nazis. In the U.S., an absence of funds by museums has stalled provenance research, and equally if not more discouragingly, the museums began to defend cases by claimants on grounds like statutes of limitations, laches and jurisdiction, which is contrary to the intent and spirit of the Washington Principles.

Did you see the Gurlitt case as a turning point in this whole discussion?

Potentially, yes, because it brought back the world’s attention to an issue which had faded to the sidelines so many years after the Washington Conference. It was such a dramatic find. And the discussion to me showed that the Washington Principles are still alive.

The Washington Principles didn’t cover private collectors. Is this something governments could do more about? Could there be more international pressure?

The Washington Principles were not limited to public museums, and could cover private museums and galleries as well. However, personal and family collections are a huge gap, but we couldn’t bite off more than we could chew in 1998. Just getting museums to sign on in the United States was difficult.

You said in your concluding remarks at the Washington Conference that the goal was “to complete by the end of this century the unfinished business of the middle of the century.” That was definitely too optimistic – we are now 18 years into the following century. How long do you think this subject will remain with us?

It was important to set a goal to stimulate action, and it did. Just think of where we were before 1998. We would not be anywhere without the Washington Conference on Nazi-Looted Art and the Washington Principles. It has led to the restitution or compensation for hundreds of works of art and it has also revolutionised the whole issue of provenance of art. But where are we now? It’s a glass that is maybe slightly more than half full. There are still major gaps. How long will we be at it? As long as there is a political will to focus on it. That is why the Berlin conference in November is so important, for which I credit the German government for calling as a stock-taking opportunity. I hope it will stimulate countries to try to demonstrate what they have done and point the spotlight at those who have not acted. It’s an enormously important event to provide some new momentum 20 years later. I am more optimistic than pessimistic, given how far we have come in the past two decades.

Stuart E. Eizenstat

Ambassador Eizenstat initiated and hosted the Washington Conference in 1998. He has held a number of key posts in various U.S. administrations, serving as chief White House domestic policy adviser to President Jimmy Carter (1977-1981); U.S. Ambassador to the European Union (1993-1996); Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade (1996-1997); Under Secretary of State for Economic, Business and Agricultural Affairs (1997-1999); and Deputy Secretary of the Treasury (1999-2001). He is the author of Imperfect Justice: Looted Assets, Slave Labor and the Unfinished Business of World War II (2003) and most recently, President Carter: The White House Years (2018).