The municipal collection of modern art, built up from 1945 onwards, has been a pillar of the Nationalgalerie since 1968. Provenance researchers at the Zentralarchiv (Central Archive) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin) have investigated about five hundred of these works to check whether they might have been confiscated under Nazi persecution. Christina Thomson reveals how she and Hanna Strzoda pieced together the pictures' biographies and explains why Berlin needed a new collection of modern art in 1945.

Why did the city of Berlin begin to assemble a collection of modern art right away in 1945?

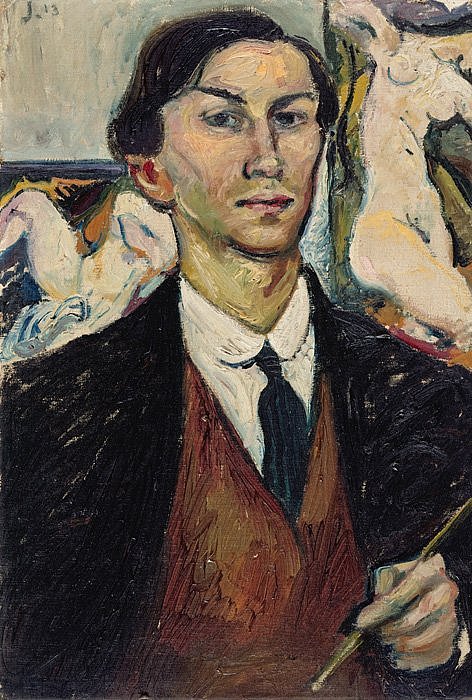

Berlin's cultural figures wanted to repair the gaping holes that the Nazis had torn in the existing collections. Works of modern art had been confiscated, coercively transferred , looted, or denounced as degenerate, while many artists had to emigrate or were no longer allowed to work freely.

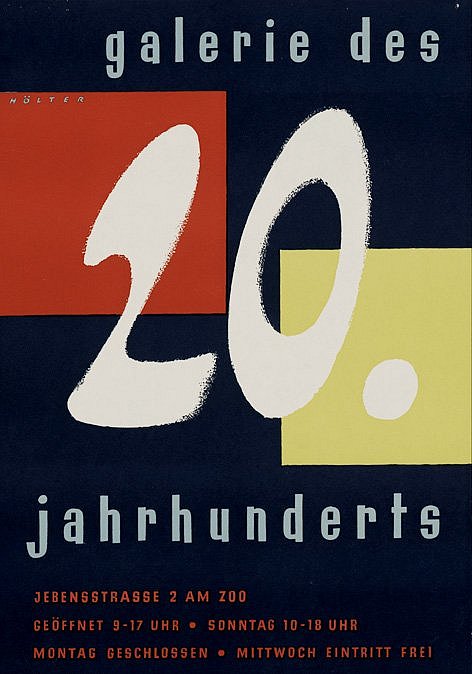

The Gallery of the 20th Century was conceived as a new platform, which would make reparation in two ways: it would help to support living contemporary artists and it would bring those who had been ostracized and expelled back into the limelight.

It was originally an initiative by the Berlin Magistrat – the executive city council – in the period immediately after the war. Not long afterwards, however, the city was divided and the GDR – East Germany – was created. The nucleus of the new collection remained in the eastern part of the city. The gallery was re-established in the western sectors and over the following years it grew considerably. In 1968, the western collection was exhibited, on permanent loan from the Federal State of Berlin, together with the collection of the Nationalgalerie in Mies van der Rohe's new museum building at the Kulturforum.

Federal President Theodor Heuss leaving the recently opened Gallery of the 20th Century in Jebensstrasse. Beside him on the right is Otto Suhr, the Governing Mayor of Berlin; behind them is Adolf Jannasch, the gallery's director (January 29, 1955) © Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290(05)Nr.0107995 / Gert Schütz

How did they go about it in practice? Was it difficult to buy modern art after twelve years of ostracism and persecution?

The situation in West Berlin was certainly more difficult than in West Germany, on account of the city's political and physical isolation. Nonetheless, the network of contacts with people based in West Germany worked well. In addition, Adolf Jannasch, the head of the gallery in West Berlin, had good relations with many living artists, and the purchase committee always included at least one or two artists. This network made it possible for him to buy many works directly from various artists. That is why the gallery has such a strong focus on Berlin – in respect both of the art market and of the artists.

One of the difficulties when making purchases is, of course, the need to stay within budget. How can you buy modern art of sufficiently high-quality on a limited budget? The main thing to bear in mind when you look at buying and collecting in the post-war period is the sudden jump in prices during the mid-Fifties. In the Forties, you still got a lot of art for a little money, but in the course of the Fifties prices rose sharply; art became so expensive that by 1960 you could only afford to concentrate on individual pieces.

What kinds of ownership path did you ascertain for the pictures? Is there such a thing as a “typical biography“ of a work?

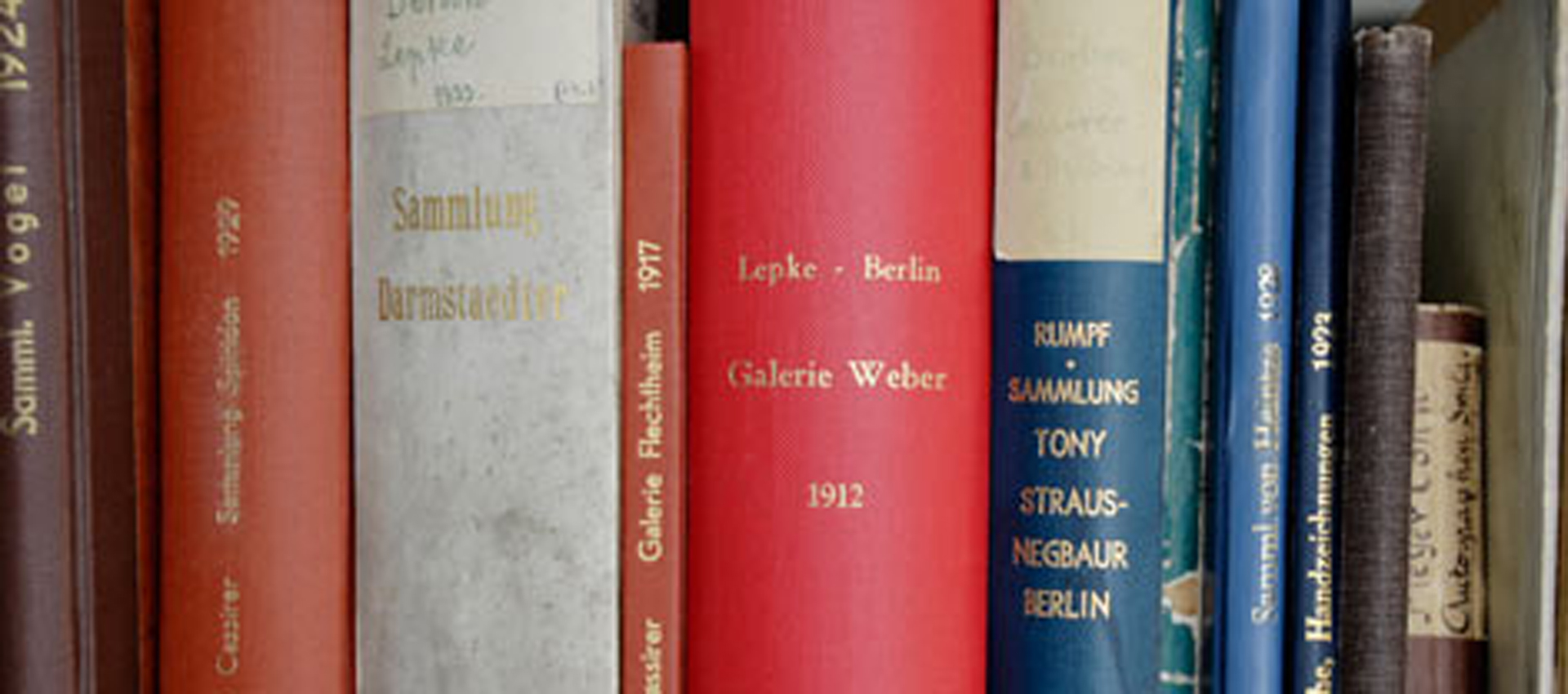

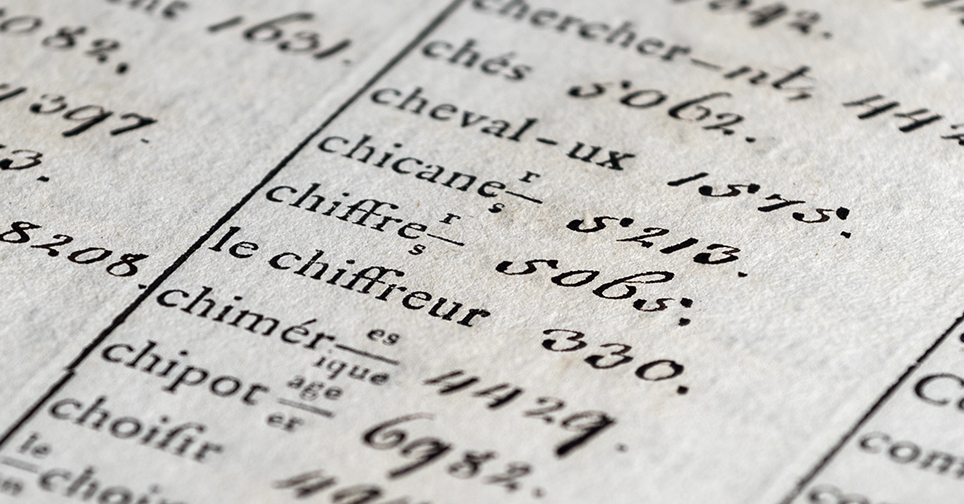

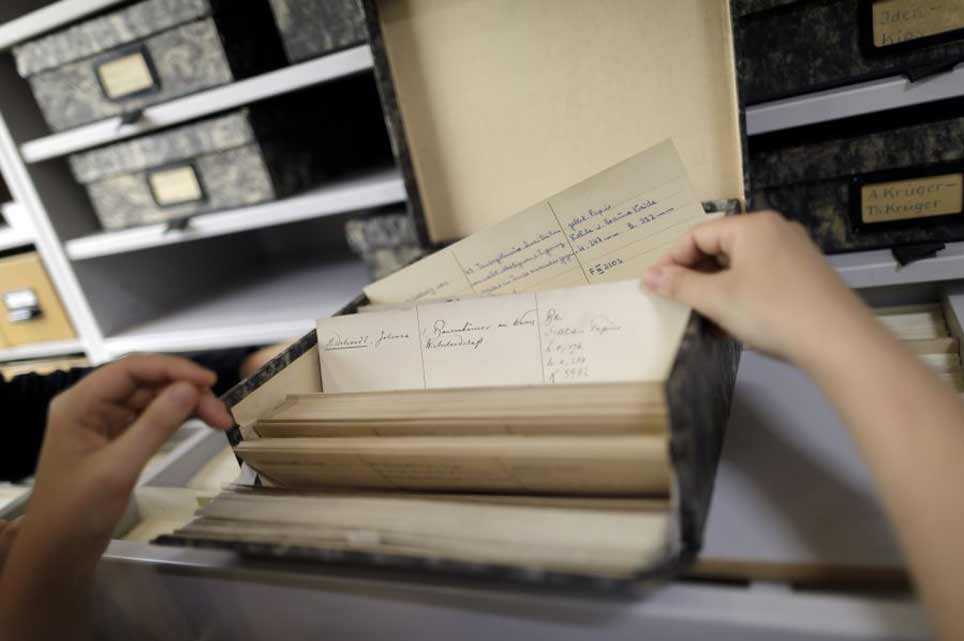

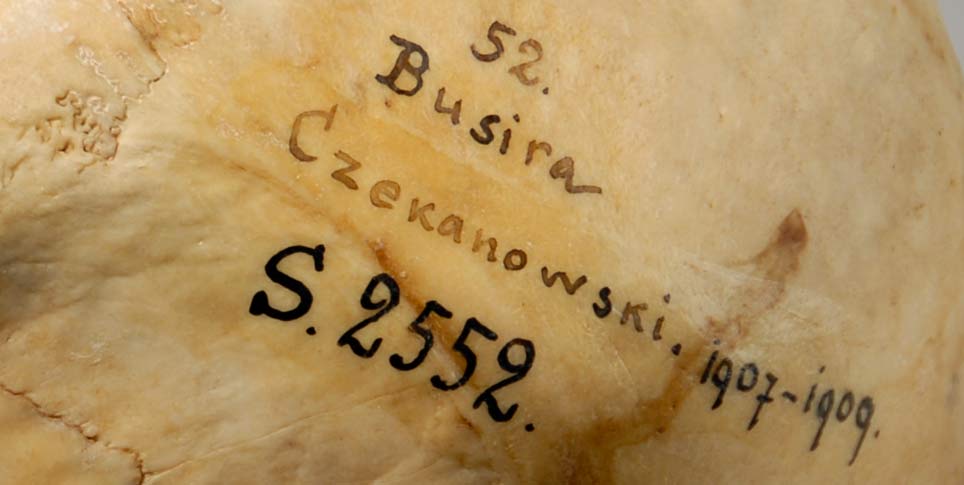

For this project, we researched the provenance of the pictures dating from before 1945 that were acquired in West Berlin and are kept in the Nationalgalerie and the Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings) on permanent loan.

That's around 500 works of a collection totaling around 1700. The objects that we investigated can be put into a number of categories: some were bought directly from the artists or from the trustees of their estates – which of course is always a nice starting point as far as provenance research is concerned. Then there is a small number of works that were defamed as “degenerate art“ by the Nazis and confiscated from public collections on their orders, but which went onto the art market and thus eventually ended up back in the Gallery of the 20th Century. That leaves a relatively large group of works that can only be regarded as isolated cases. Here you can identify networks, but cannot ascertain a “typical biography“ that could be regarded as exemplifying others. Provenance research demonstrates that each work has its own history.

Sometimes purchases fall into patterns or come in groups consisting of smaller collections – that helps with research. For instance, one collector, city councilor Heinrich Evert, donated more than sixty works to the Gallery of the 20th Century. Another kind of group consists of works by an important artist, such as Edvard Munch or Max Beckmann, which were crucially important components of what later became the Nationalgalerie collection. Many pictures, including some of those by Beckmann, came to the gallery through Jannasch's contacts with collectors and other art experts. The cultivation of contacts with widows or estate trustees was another important way of getting hold of works.

So do you now know the origins of all the five hundred works that you researched?

We have traced the ownership paths of all of these works. Despite intensive research, we have not been able to clarify every aspect down to the last detail. That is normal, however – especially in the field of graphic prints. Even if a work's provenance does have gaps, you can often exclude the possibility that it was confiscated in relation to Nazi persecution. And we've made all our results available on a web site: www.galerie20.smb.museum. So now anyone who wants to can find out for themselves. It was very important to us to have transparency. As far as I know, there is nothing comparable to it so far.