What an object had to go through to arrive at its present location is often difficult to trace. "Susanna" by Reinhold Begas is an example.

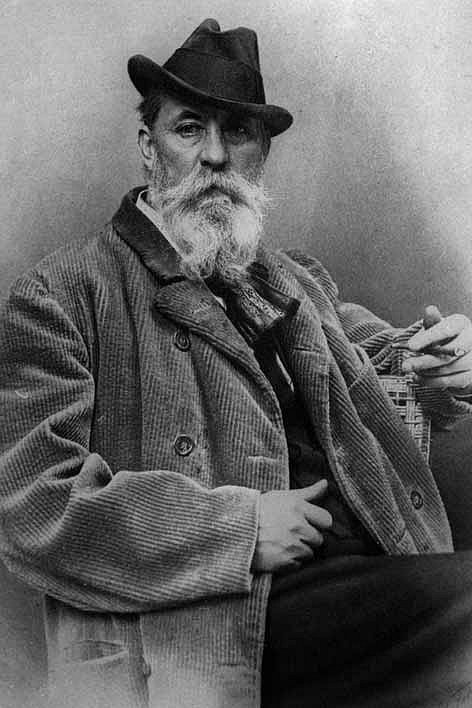

Sculptor Reinhold Begas (1831–1911)

Reinhold Begas, a native of Berlin, was born into a respected family of artists. Two pioneers of the Berlin school of sculpture mentored young Begas both artistically and personally: Johann Gottfried Schadow, who was older, and his student Christian Daniel Rauch. As Reinhold Begas’ godfathers, both were closely connected to the family and they both introduced him to the art of sculpture.

"Susanna" by Begas in the Alte Nationalgalerie © SPK / Birgit Jöbstl

Remarkably, Begas was able to separate himself from his two role models at an early stage. He managed to revolutionize Classicism, which had become rigid, and with his fluid, sensual works, he was celebrated as the “reformer of the Berlin school.” His return to Baroque forms went down in art history as “Begas style.” Like many other 19th century artists, Begas went to Rome to study the eternal city’s Baroque and ancient artworks. His lifelong friendship with painters Arnold Böcklin and Anselm Feuerbach also began in Rome. Begas’ early period was characterized by genre and literary subjects such as his Susanna. As Wilhelm II’s favorite sculptor, he later worked mainly on imperial representations.

"Susanna", the statue by Reinhold Begas

The Book of Daniel in the Old Testament relates the story of Susanna, the wife of a well-to-do Babylonian. The young woman is described as being very beautiful, and her virtue was put to a severe test in the biblical tale. Two elderly judges watched her bathing and pressured her to commit adultery. Susanna resisted firmly, which offended the two judges and they tried to have her executed for promiscuity. Susanna’s unwavering faith in God ultimately saved her.

The story of Susanna became a parable of godliness and integrity, and throughout history it has often been used as a subject in art. Its attraction consisted mainly in the opportunity to create an image with sensual appeal and erotic connotations. Begas concentrated his work completely on Susanna and decided against the art historical tradition of a group sculpture. The way the body turns, her glance, and the act of pulling up the protecting cloth points to the presence of the two old men. Begas took the cloth that was actually supposed to hide the naked body and turned it into a means of presenting its sensuousness. He focused on the voyeuristic aspect of the story to turn viewers into participants in the illicit act.

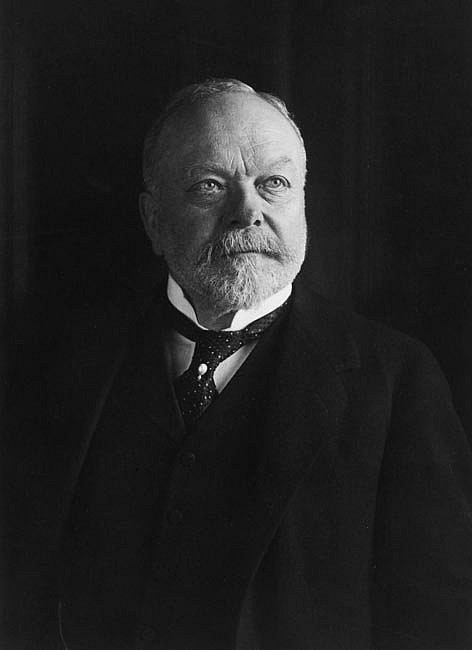

Rudolf Mosse (1843–1920)

The Jewish publisher Rudolf Mosse was one of Berlin’s lions of business during the German Empire and the early Weimar Republic. One of 14 children, he was born in Graetz near Posen (Poznán) in 1842. He completed an apprenticeship as a bookseller and moved to Berlin in the early 1860s. He worked as an advertising salesman for the magazine Die Gartenlaube and after that, founded “Annoncen Expedition Rudolf Mosse” in 1867. This was the first step in his professional and economic ascent. After only a short time, he expanded his business into the successful Mosse Verlag and published numerous newspapers, including the Berliner Tageblatt which he established in 1872, over 130 trade journals, address books, and scientific publications.

In 1912 he was considered to be the second wealthiest man in Prussia. With the considerable wealth that he accumulated through publishing, Mosse bought many properties – including several manors and Schenkendorf Palace near Königs Wusterhausen. In 1882 he also had a magnificent residence built on Leipziger Platz, “Mosse Palace,” in which he housed his major art collection. He was a generous benefactor and donor, active in social work. He supported Reformed Judaism and as a liberal interested in reform, he was also involved in politics. Mosse died in Schenkendorf Palace in 1920.

The Mosse Collection

Rudolf Mosse’s art collection, which he primarily focused on in the 1880s and ’90s, consisted of several thousand works. In 1912, Max Osborn, a contemporary art critic and journalist, called it “one of the greatest and richest German art collections.”

Starting in 1910, part of the collection was open to the public. Mosse exhibited his art collection in his magnificent mansion on Leipziger Platz; it was displayed in 20 rooms on three floors. His passion was contemporary Realist paintings with a few works from Naturalism and some Old Masters. Along with works by famous artists such as Adolph Menzel, Max Liebermann, and Hans Thoma, Mosse acquired numerous works by younger, unknown artists in order to support them financially. Along with paintings and sculptures – including Susanna by Reinhold Begas – the collection that was called the “Mosseum” in art circles included applied art, tapestries, books, Egyptian and Roman artworks, Benin bronzes, rugs, needlework, East Asian objects, and furniture.

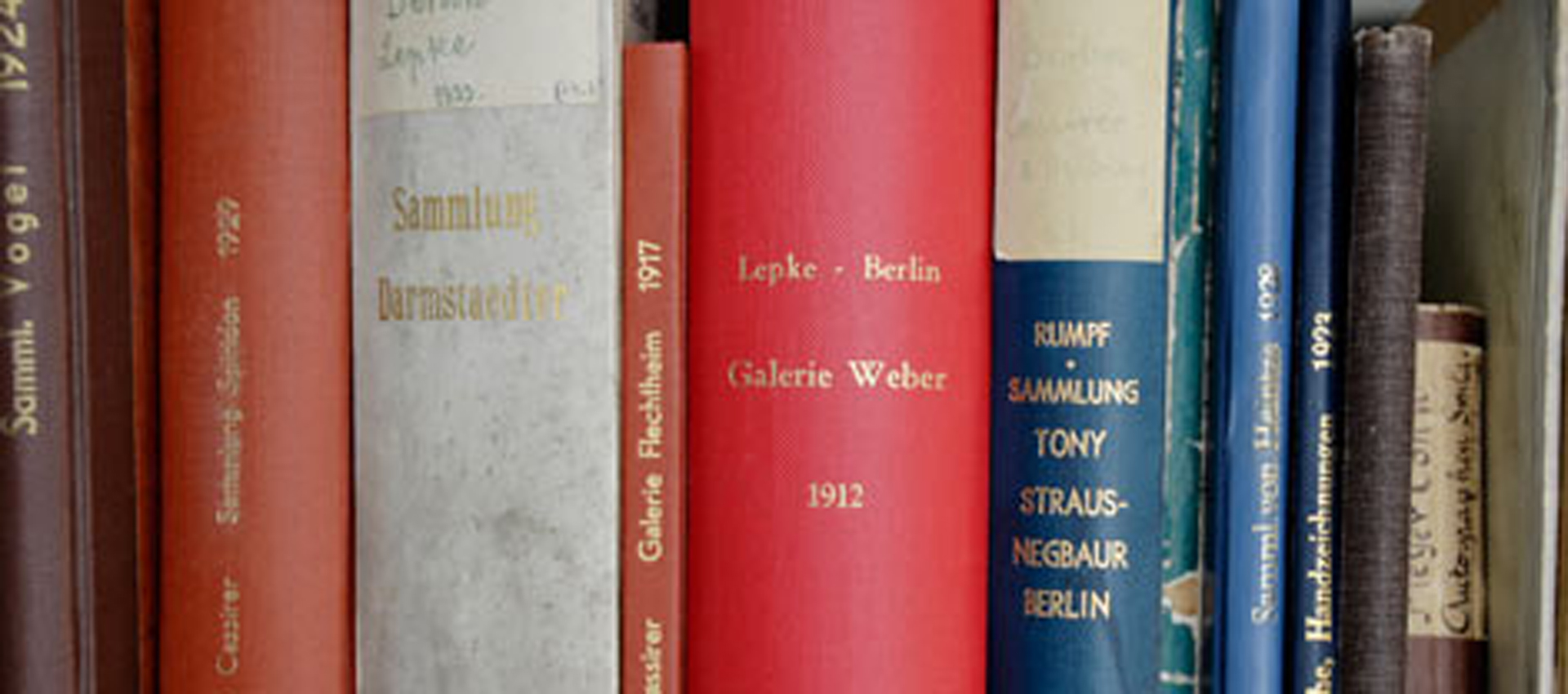

After his death, Rudolf Mosse’s adopted daughter, Felicia Lachmann-Mosse, inherited the collection. In 1933 the Lachmann-Mosse family’s art collection was impounded and transformed into a foundation. Many of the works were sold by the Rudolph Lepke and Union auction houses.

"Susanna" Provenance Overview

1897Oscar Hainauer collection (unconfirmed provenance)

1909–1933Rudolf Mosse collection

1933Removed from the Mosse collection and transferred to the Rudolf Mosse Foundation, established by the Nazis

1936Anny Lederer

1945/46Transported to Leningrad, the Soviet Union, as spoils of war

1978Returned to the Museum of Ethnography in Leipzig

1994Transfer to Nationalgalerie – Staatliche Museen zu Berlin as an ownerless object

2016Restitution to the Mosse family

2017Acquired for the Nationalgalerie

Provenance of "Susanna" by Reinhold Begas

The marble sculpture’s public biography begins in Vienna in 1873. The artist presented his Susanna to an international audience for the first time at the world exhibition. The sculpture, which weighs one ton, was not sold immediately. It came into Rudolf Mosse’s ownership in 1908 at the latest. It was displayed in the publisher’s mansion on Leipziger Platz, surrounded by works by contemporary sculptors, including a bust of Mosse’s wife by Reinhold Begas.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, the Lachmann-Mosse family’s art collection was impounded, turned into a foundation, and sold by the Rudolph Lepke and Union auction houses. Susanna was not among the works that were auctioned off. It was exhibited in 1936 by the Academy of Arts. The catalog states that Anny Lederer, the wife of Hugo Lederer, a sculptor who admired Begas, was the lender.

Apparently, in 1946 a Soviet “trophy commission” sent the marble sculpture to Leningrad from a public art storage site. It was transferred to the Völkerkundemuseum (Museum of Ethnography) in Leipzig in 1978 along with other returned objects and placed in trust with the Nationalgalerie in 1994, which has exhibited it as an ownerless object since 2001. In 2017 the sculpture was restituted to the heirs of the Mosse family and then acquired with the support of the Kulturstiftung der Länder, the German states’ cultural foundation.

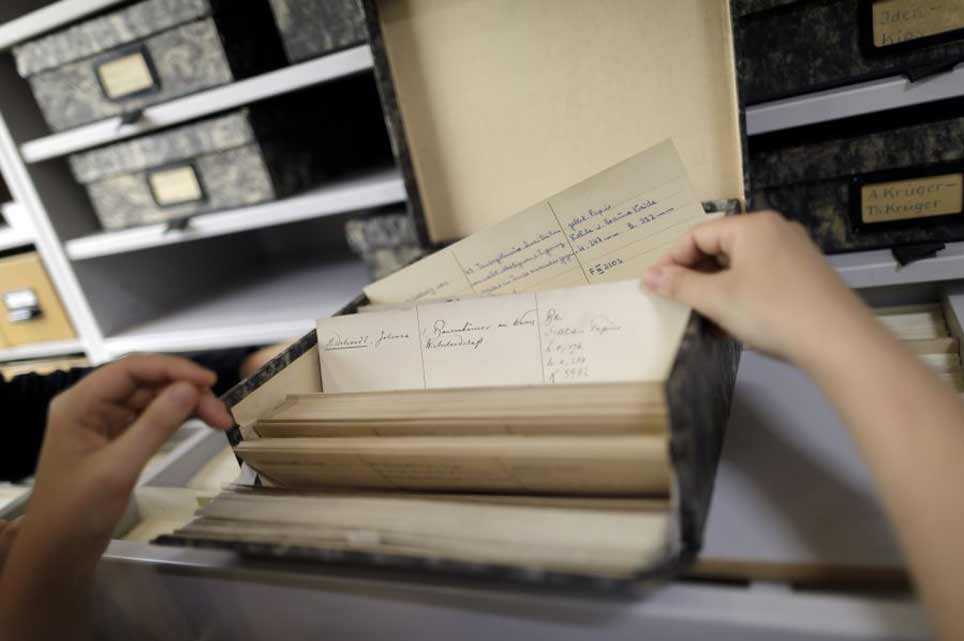

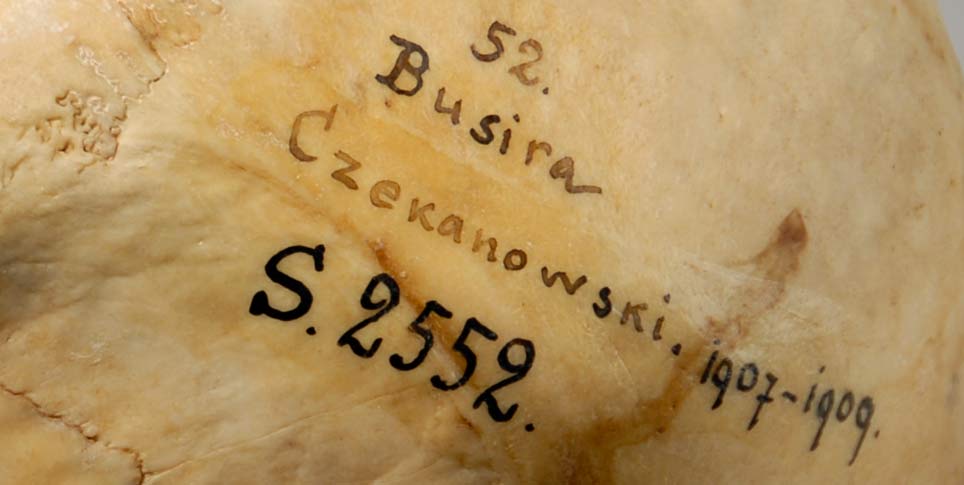

Provenance research project on the Mosse collection – project partner MARI

The collection of German-Jewish publisher Rudolf Mosse comprised thousands of pictures, sculptures, applied arts objects, books, and antiques. Together with the heirs of the Mosse family and other project partners, scientists from Freie Universität Berlin have been researching to locate the works that were seized by the Nazis.

The Mosse Art Research Initiative (MARI) is a collaboration among the university, museums, archives, and the Mosse family heirs. It is the only provenance research project of its kind in the world. As an independent research institution, it is not involved in any restitution processes, therefore Freie Universität Berlin is head of the project and it is directed and coordinated by Prof. Klaus Krüger and Dr. Meike Hoffmann. The Cultural Foundation of the German States, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin), the Jewish Museum Berlin Foundation, Landesarchiv Berlin, Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe, Wallraf Richartz Museum in Cologne, Museum Wiesbaden, Worms Museum, and Mathildenhöhe Darmstadt are all cooperating partners. The Zentralarchiv (Central Archive) is the internal Staatliche Museen zu Berlin partner. It also researched the objects from the Mosse Collection in the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. The research project is supported by the German Lost Art Foundation in Magdeburg and the Mosse Art Restitution Project.

Additional Information

The Mosse Art Research Initiative (MARI) identifies and localizes artworks that were owned by Rudolf Mosse and his family. This includes retracing the works’ individual stations and paths to their current locations and clarifying the exact circumstances of loss during the Nazi period. Another goal is to find out more about the system initially used by the Nazis to dispose of disowned cultural objects.

Freie Universität developed a website to present, explore, and visualize the complex MARI research results digitally.

The Mosse Foundation reports on progress in the restitutions on their website: The Mosse Art Restitution Project.