MacKenzie Mallon works as the provenance specialist at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and is a participant of the German-American Exchange program on provenance research (PREP) this year. She told us about her recent research on a Lionel Feininger painting where she also used information from the Zentralarchiv.

MacKenzie, you are working at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art as theprovenance specialist. Can you briefly explain what kind of museum this is and what it collects?

The Nelson-Atkins is an encyclopedic museum. We collect art objects from cultures around the world, all the way back from antiquity up to the present day. In addition to our European and our American collections, we are especially well known for our Chinese art and our photography collection.

MacKenzie Mallon © privat

What is your job at the museum?

My specialty here at the Nelson-Atkins is Nazi era provenance and the research for Nazi-looted art. I have a long term project to research all the European works in our collection for which we do not have complete provenance between 1933 and 1945. I also do special projects when questions come up, maybe for new acquisitions, or if we find something that we need more information about. , Alll the curatorial departmentsconduct provenance research and I am here to help them with any problems they may have and to support them in that research.

When you speak about your long-term project, long term means a few of years, I suppose?

I’ve been doing this six years and we just finished the paintings - so it is long. We have over 40 000 objects…

So there’s still some work for you to do. Could you tell me about your recent research, was there anything special last year?

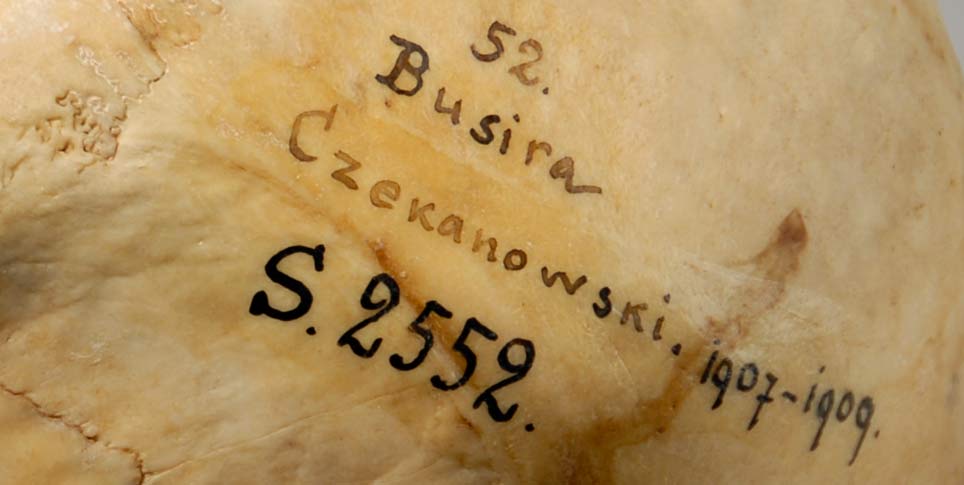

In the last year, I’ve been researching all of our modern paintings, especially the German expressionists’ works. Then Scott Heffley, senior conservator of paintings at the Nelson-Atkins, told me about slashes in the canvas of our Feininger, “Gaberndorf II”. He suspected that perhaps the painting had been a victim of the “Degenerate Art” campaign. It very well could have been, as Feininger certainly was in Germany until 1937. We decided that we needed to find out when the painting was in Germany and when it left and try to find some more information about it. So I moved that painting to the top of our list.

How did you start with the research?

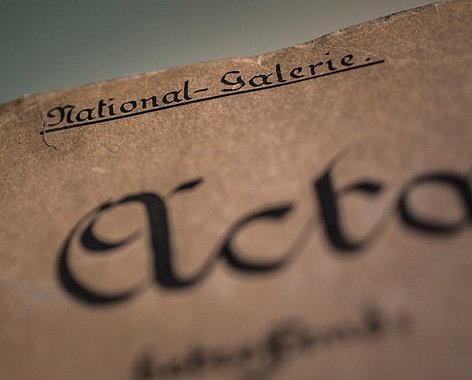

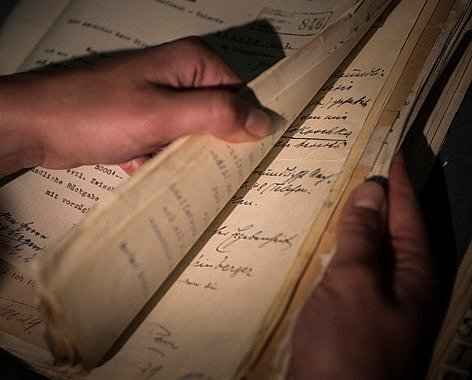

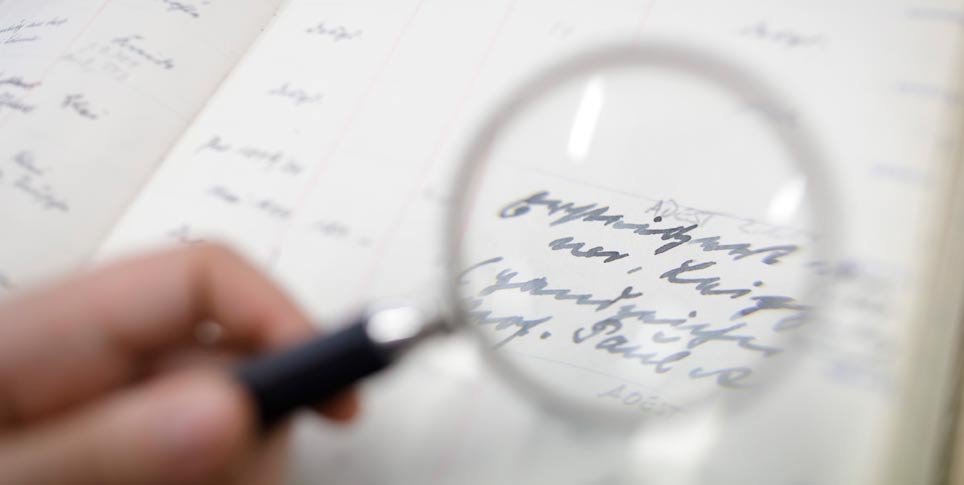

I started with what we knew about the painting’s history from the catalogue raisonné and the records we had in our files. One of the things we knew was that it had been on exhibit at the National Gallery in Berlin in 1931 to 1932. So I contacted the Zentralarchiv of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin and asked them if they could send us any documentation they have regarding who lent the painting to the exhibition. The painting was created in 1924, so if we knew who had lent it to the exhibition in 1931 that would give us a big clue as to its owner before the war and possibly where it might have been during the war. The colleagues at the Zentralarchiv were so kind and helpful. They sent me scans of their records which enabled us to determine that the painting had been lent to the exhibition by Feininger himself, which was very interesting. At that point we needed to find out how long Feininger kept the painting and if he sold it before the war.

What about the slashes?

The next step was that I went through Feininger’s letters published by his wife. I finally found some from 1925 in which Feininger actually described slashing the painting himself! This was a real surprise to us. He was not happy with the composition right after he painted it and decided to destroy it. But a couple of weeks later he had a change of heart and decided to repair it. And he actually kept it with him for many years after that. It was a relief to us that it wasn't a victim of the “degenerate art” destruction, of course. And to find that information really helped our research a lot.

Then how did you proceed?

We knew from the letters that Feininger was the one who slashed it. We knew that he had lent it to the National Gallery Exhibition in 1931/32. So from that point on, it was researching where else he had lent it to exhibitions. The painting had been shown in a numberof exhibitions between 1932 and 1945. So I had to contact the museums in Germany and here in the US to find out whether he was the lender or whether someone else had lent it. It turned out that in every case Feininger himself had lent the painting to German exhibitions and to American exhibitions.

How did you find out at which museums the painting had been on display? Apart from the Nationalgalerie you had no information about them. Or was it also in the catalogue raisonné?

A lot of it was in the catalogue raisonée. To find some of them was just by chance, looking in exhibition catalogues of Feininger’s work and trying to match up works that were in these exhibitions with ours. I requested copies of exhibition catalogues; as many as I could get my hands on. Dozens and dozens of exhibition catalogues of Feininger’s paintings. A lot of it was looking for a needle in a haystack. But when we were able to find that he lent it to a US exhibition in 1937, then, at that point, we knew it was in the States by 1937. That was helpful.

When did the Nelson-Atkins acquire the painting?

We acquired it in 1946, right after the war. And we now know that Feininger lent it to a lot of exhibitions between his return to America in 1937 and our acquisition in 1946. They were all in the US. He kept it with him throughout the war.

When did the Nelson-Atkins acquire the painting?

We acquired it in 1946, right after the war. And we now know that Feininger lent it to a lot of exhibitions between his return to America in 1937 and our acquisition in 1946. They were all in the US. He kept it with him throughout the war.

Did you find out when he actually sold it?

He gave it on consignment to a dealer in New York in 1946 and we bought it from them the same year. So Feininger had the painting with him for over 22 years, which is interesting considering the fact that when he first painted it, he didn’t like it and destroyed it. And then he put it back together and kept it with him for decades!

Did you find out anything else about his personal feelings for this painting, and were you able to fill all the gaps in the painting’s history?

Just what he said in his letters about it, right after he created it. That he didn’t like it and then that he repaired it. About two months later he says in his letters that now he is really pleased with it and thinks that it is one of his best works and that he is seeing it in a different light. I think the one thing I wish that we could find that I haven’t been able to determine is the exact date that Feininger shipped the painting out of Germany to the US. There is a really faded purple stamp on the back of the painting that looks like a customs stamp. So I contacted customs stamp experts all over Europe from different countries asking them if they could recognize the stamp. Eventually I was referred to the Czech General Director of Customs, who identified it as a Czech customs stamp probably dated from just before World War II. This corresponds with Feininger’s departure from Europe in 1937. I suspect that he probably shipped the painting right then in 1937 the same time that he left Germany. But the details of the exact time and the method of shipping is something that is not very easy to find.

And how long did the research take all together?

Four months.

Did you spend all your time on that one painting?

No, one always has to wait for answers. A lot of times I’ll find myself working on ten or twelve works at the same time and it can get a little confusing. Documentation, taking notes of what I’ve done and what I still need to do is really important. Otherwise I’d lose my place.

Did you have any contact with the Zentralarchiv of the Berlin museums before for any other research or was this the first time you approached them?

Yes, a couple of years ago I had asked them about a Signac painting in our collection. They were able to identify a label on the back of the painting as from the Moderne Galerie Thannhauser, which was extremely helpful to me. I have to ask a lot of people a lot of things and when you are working in the US on European works of art a lot of research that you need is obviously not at your fingertips. My museum is very supportive with travel-funding, but I can’t spend all of my time in Europe. Since I can’t get there very often I try to combine a lot of research into one big trip. If I need something quickly or something small, then I have to rely on the kindness of people over there. I have to rely on archivists and museum staff and researchers in Europe a lot. I couldn’t do this kind of research without their help.

Whatever is digitized is already a big help, I suppose.

Oh yes, absolutely. I think it’s helpful for all researchers whether they are in the US or in Europe. Certainly digitization makes things so much easier since you don’t have to leave your desk. The Getty databases for example, they are huge. They put so much on their website, but they have so much more that is not digitized. The Getty is actually one of my most frequent research trips. They have so much available there.

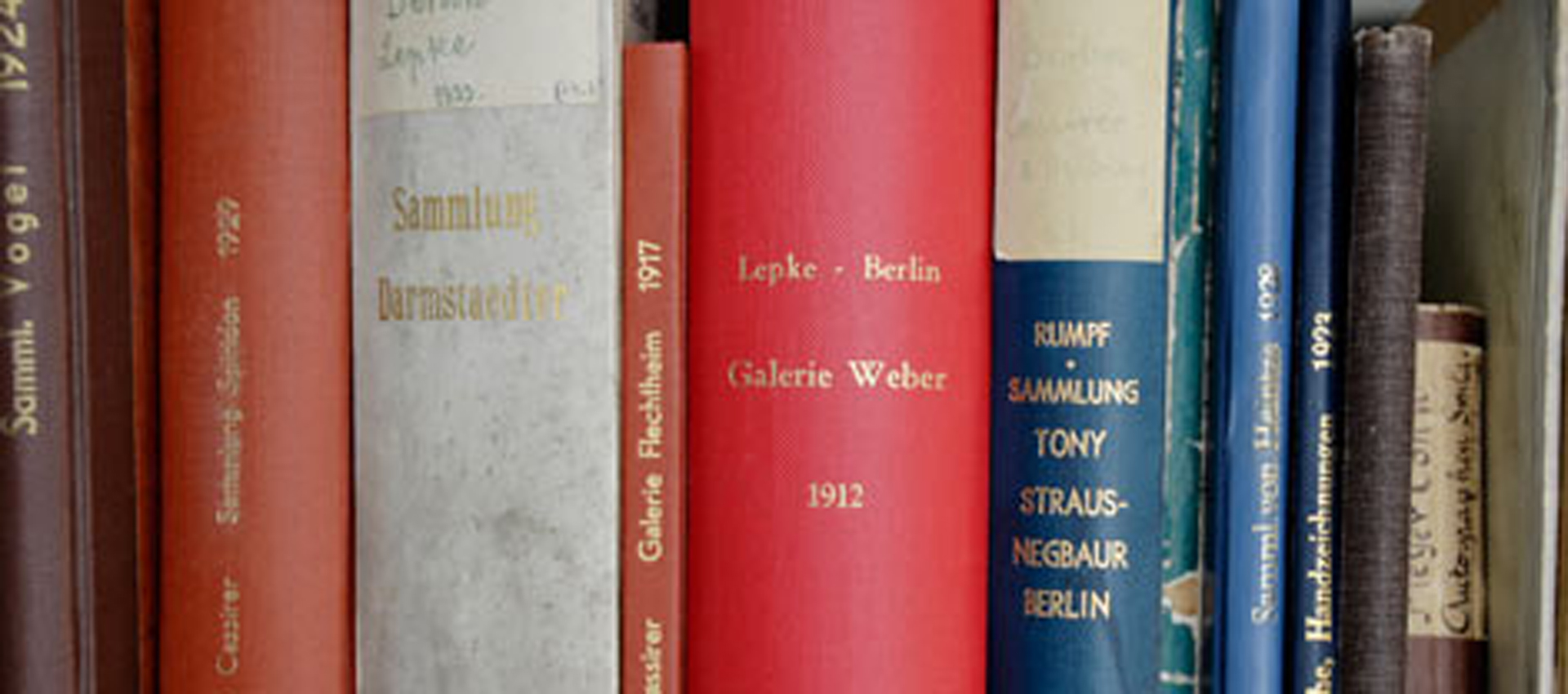

One of our institutes also has a digitization project on the auction catalogues of the years 1930 to 1945. Did you ever come across those as well?

Yes, I use them all the time! They are connected to the Heidelberg University and to the Getty. I think they are extremely helpful.

Is being part of PREP helpful for your work as well?

The February PREP was really a revelation for me. It far exceeded my expectations. The on-site visits to the archives in New York were very helpful and interesting. But by far the best part of the program was meeting other provenance researchers, especially the Germans, because we are doing the same work on two continents. But before PREP we didn’t speak to each other enough. I didn’t realize how different provenance research is in Germany. It seems that so much of the German research is project-based and government-organized whereas in the US we are usually employed by individual museums or we work independently. The Germans therefore seem to be much more connected to each other, their work seems more collaborative. In the US, the researchers talk to each other a lot, but I don’t think we do to the extent that the Germans do. So there is so much that we American researchers can learn from them. Hopefully they can learn something from us Americans too! I think the September PREP-meeting will be just as good as the New York one. I am not as familiar with the German archives so it will be really great to learn more about them and especially to have the German researchers there to help guide us through them and give us pointers.

Do you have anything that you would like to share, something I didn’t ask but you think is important?

The most important thing that I would want to convey is how grateful I am, and I think many American provenance researchers are, that our European colleagues are willing to collaborate with us. It means a lot to us to have the opportunity to work alongside them, to meet them at PREP, to share ideas and to broaden our understanding of this field by sharing our common experiences and working on similar problems together. I hope we can continue our collaboration, I hope that we can do even more work together in the future. I think that PREP is an excellent starting place for that kind of collaboration.

Can you finally tell me what is your personal background, how did you start with provenance research?

I kind of fell into it. My undergraduate degree is in history, but my Master’s degree is in art history. I’ve always loved history and the fascinating stories that go with it. So about six years ago I was working as an assistant in the European department at the Nelson-Atkins and the curator at the time asked me if I could help her with some Nazi Era provenance research. She knew that I had studied both history and art history and that I knew some languages including German, so I started to do some provenance research as a side project and I really enjoyed it. So I made it a point to learn as much as I could about the field. Then in early 2015, when I was asked to consider doing provenance research fulltime, I jumped at the chance. I have been a provenance specialist ever since. The Nelson-Atkins is fully committed to provenance research on its collections and it’s wonderful to work in a museum that’s so supportive.