A project to establish the origins of East African human remains starts in October 2017 at the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte (MVF) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. Bernhard Heeb, curator of the MVF and manager of the project, explains why the museum has a skull collection and how it is being investigated.

Mr. Heeb, what is the story behind the thousand skulls from East Africa?

The skulls belong to a larger collection, known as the S-collection, which was assembled by physician and anthropologist Felix von Luschan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Originally this collection contained around 6,300 skulls. Almost 5,500 of them still exist in Berlin.

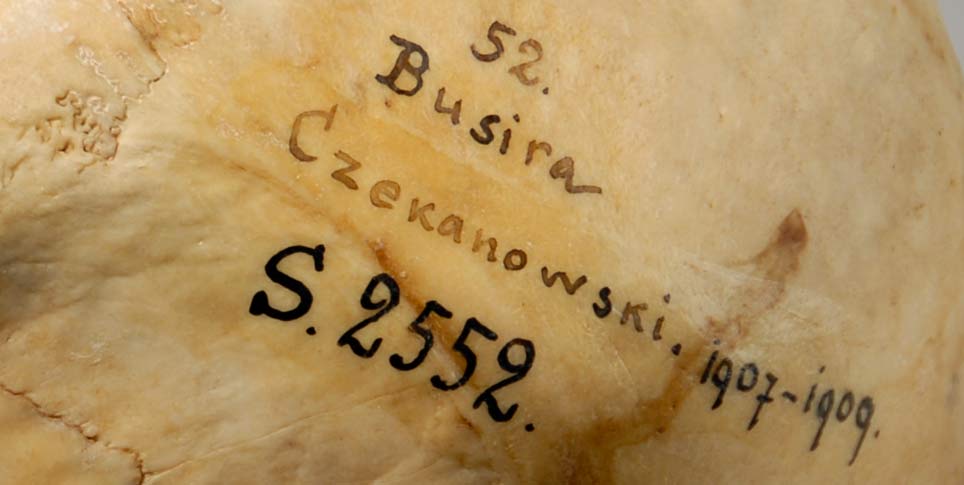

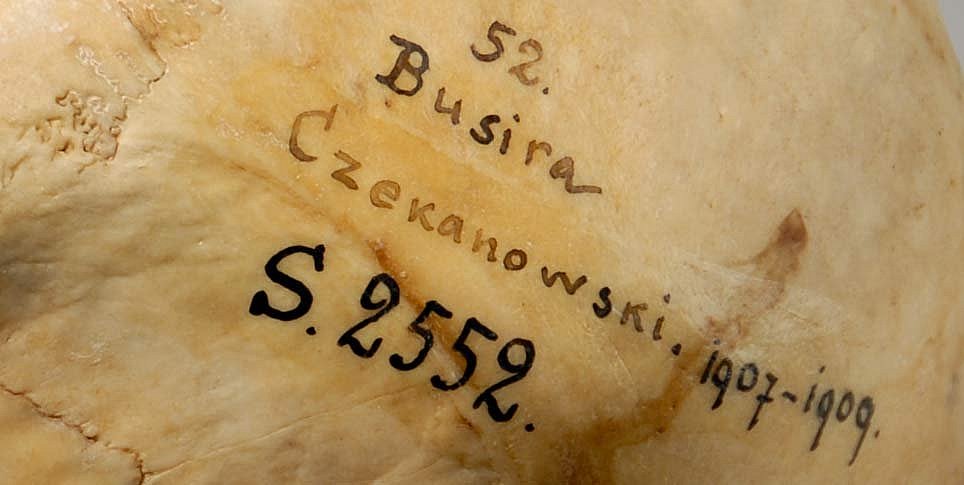

Writing on a skull © Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte

What did von Luschan plan to do with them?

He wanted to study the development of the human race by analyzing the bones. To him, they were simply sources of factual information for this purpose.

And from a scientific perspective, it is generally true that the more data you have, the more accurate the results are. That's why he obtained a large number of skulls from a variety of countries. Some of them are archaeological remains: from Egypt, Central America, and South America, for example, as well as from early medieval tombs in Europe. But in many other cases, we do not yet know how old they are, only where they have come from.

A considerable proportion of them was brought from the German colonies in Africa and the Pacific region – a historical background that makes it essential to establish their provenance. At least we are now able to begin a closer investigation of the thousand or so skulls from East Africa, thanks to a grant from the Gerda Henkel Foundation.

How did von Luschan manage to accumulate so many in such a short time?

For one thing, the collection was not acquired all at once, but was built up over a period of about thirty to forty years. For another, Felix von Luschan, as far as we know, did not go on such expeditions himself. As a curator at the forerunner of the Ethnologisches Museum (Ethnological Museum), he was able to call upon a network of collectors that covered almost every part of the world. So he commissioned these collectors. Sometimes a delivery of several dozen skulls would arrive, and then nothing for a while. However, none of them were labeled until they got to Berlin and some were inventoried much later, which makes it difficult to say now exactly where they came from.

How did the S-collection end up in the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte (Museum of Prehistory and Early History)?

That is a long story. The collection was assembled from 1885 onward at the Museum für Völkerkunde (Museum of Ethnology) in Dahlem, where von Luschan was directorial assistant. When he became a professor at the University of Berlin in 1909, the collection went there with him for organizational reasons. After his death in 1924, the collection was transferred to the university's pathology department, and later to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology in Berlin.

During the war, it was put into safe storage elsewhere, like many art and cultural objects. In 1948, it reappeared in the cellar of the Marstall building of the Berlin Palace. We do not know how it got there. After that, the collection went to the Charité, where it joined the hospital's other anthropological collections for many years as part of the Museum of Medical History.

In 2010, the museum concluded that it was no longer able to give the skulls adequate care. Because a considerable number of the skulls are archaeological remains, and because we are very conscious of the special responsibility owed to this collection, which needs to be examined with modern methods, it has been taken on by the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte.

What is this collection needed for now? Could you not simply return it?

In order to return something, you first have to know where it comes from. Then you can decide where the objects should go and who they should be handed over to. That is why we are researching the exact provenance of the remains. If this turns out to be uncontroversial and the skulls were not obtained in a context of injustice, then they could actually be used for science again. For example, scientific methods from fields such as palaeogenetics can be used to study long-established diseases such as malaria – and resistance to them – and can thus help in developing cures and therapies today.

Moreover, isotope analysis can be used to identify the region in which an individual grew up. If the remains were found at a site far away from that region, we could potentially trace individual migratory movements, or even patterns of settlement. Examinations of this kind can only be carried out, however, if we are perfectly certain that they are justifiable from moral and ethical points of view. If we discover that skulls have a context of injustice, we must find an appropriate solution. One possibility is to return them.

If we establish that its context involved injustice, then the skull cannot become a subject of scientific inquiry.

What would count as a context of injustice?

Regarding Africa especially, some accounts mention executions by the colonial authorities; that context would clearly be one of injustice, but to the best of our current knowledge, we have no such skulls in the Luschan collection. The question is more difficult in the case of historical burial grounds: there you have to examine every single case carefully.

The important thing, however, is that if we establish that its context involved injustice, then the skull cannot become a subject of scientific inquiry. The next step is to clarify what to do with it: whether it would be appropriate to return it, or to hold a funeral – and if so, how and where it should take place. A variety of solutions are conceivable, and they need to be worked out together with the countries of origin.

What methods do you use for provenance research?

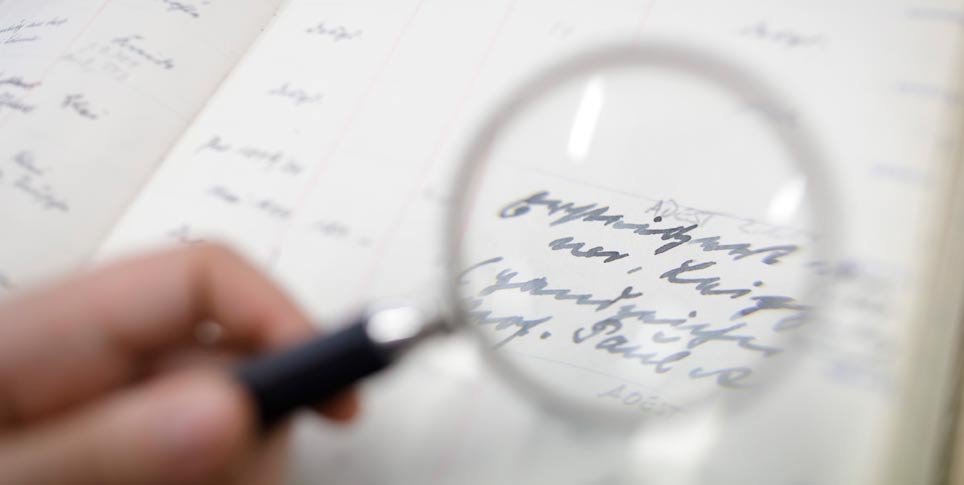

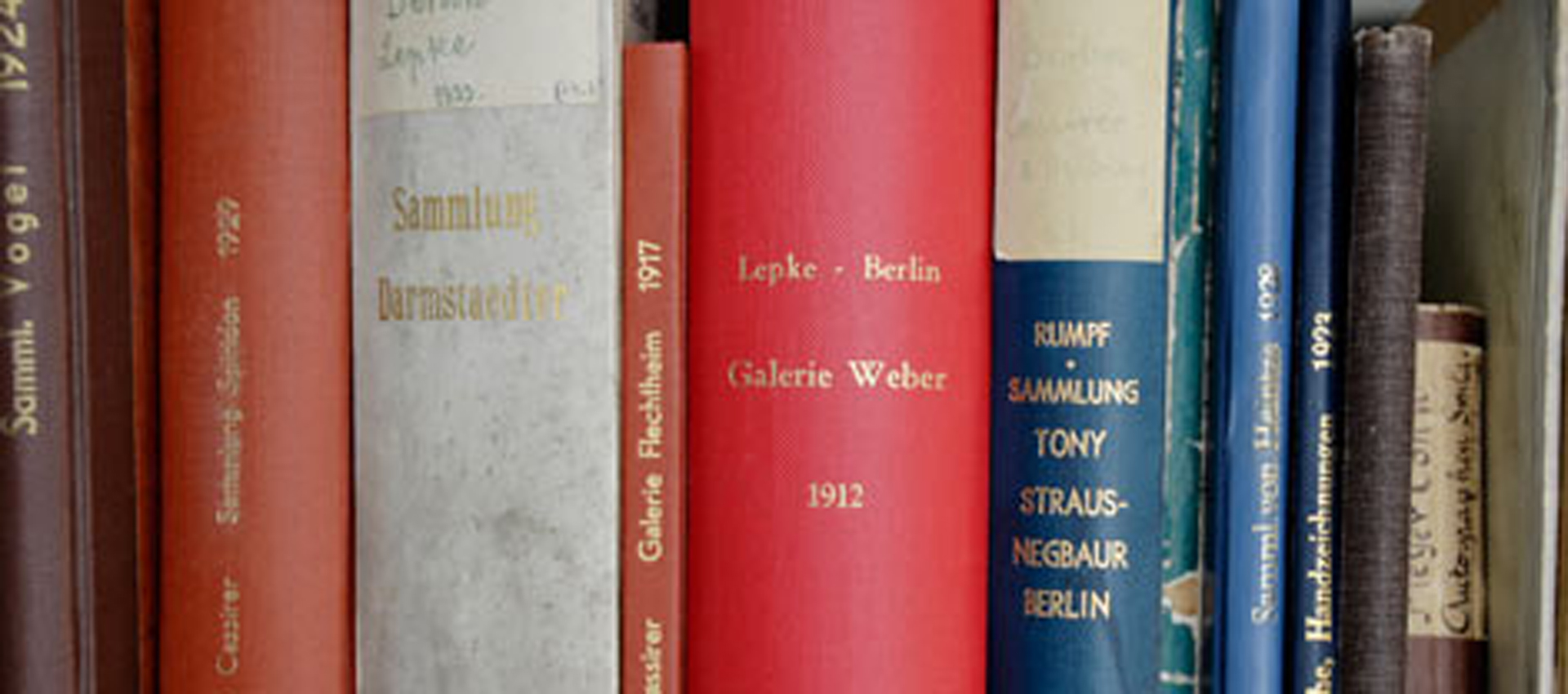

We use various sources in trying to establish an object's provenance. Unfortunately, nearly all of the primary documentation – that's the inventory register, the card catalogue and any correspondence about the acquisition of the collection – was lost during the war. Fortunately, some information has been written directly on many of the skulls. And documents have survived in various archives in this country and abroad. For example, the documents for von Luschan's personal collection still exist – they are in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. There were certainly overlaps among the acquisitions made for the two collections.

What have you found out up to now, and how exactly do you carry out the research?

From the information written on the skulls and from the sources that we have had access to so far, we know that over nine hundred skulls from the former colony of German East Africa can be traced to an area that is now part of Rwanda. There is evidence that they were obtained by Polish anthropologist Jan Czekanowski during an expedition in 1907–1908.

He collected the skulls in several different places, however, and many of them had been removed from burial grounds. Our next step will be to visit the known provenience sites in the country of origin and – insofar as it is still possible – record any relevant knowledge handed down orally, in the hope of learning how long each burial ground continued in active use. And of course, we are also trying to gather more information from the public archives in the countries of origin. We are doing that in collaboration with local scholars.

Is this really up your street, as a specialist in prehistory and early history?

The project grant has enabled us to fund posts for an ethnologist, an anthropologist, and a museologist. This interdisciplinary team is necessary in order to be able to investigate the origins of the collection. Archaeology has a part to play too, of course, when it comes to chronological classification.

The collection has been in the care of the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte since 2011. Why have you only begun researching the provenance now – and why only that of some of the skulls?

Unfortunately, the collection had not been properly stored at the Charité. We first had to clean the objects painstakingly, take measures to preserve them, and then document them with all of the available information. We worked very quickly to get all that done.

What does that mean in detail?

Some of the skulls were broken, so we put that right as far as possible. We removed the dirt and mold from them very carefully. Overall, it was a laborious task, but if we had not done it, the collection would have decayed in the meantime and would thus have been lost. Today, all of the skulls are stored with the dignity they deserve. Our next steps were to create a new inventory (checking the remaining skulls against the old lists in the process), and to set up a research database. This is the basis of any further research. And that is what we can start doing now, thanks to the grant.

The results will, of course, be published. It is clear that this project can only be a pilot project for subsequent investigations of the entire collection. We do hope, of course, that it will also serve as a model for a general reassessment of colonial-era collections, not just the collection in Berlin.

Have any restitution claims been made?

No – as things stand at the moment, we have not received any requests for the return of items in the Luschan collection.

Felix von Luschan

Felix Ritter von Luschan (b. August 11, 1854, in Hollabrunn near Vienna; d. 1924 in Berlin) initially worked as a doctor. He qualified as a lecturer in anthropology in Vienna in 1882, and again in Berlin in 1888. In 1885, Adolf Bastian appointed him as directorial assistant at the Völkerkunde Museum (Museum of Ethnology) in Berlin, where he was responsible for the Africa-Oceania department. It was Africa that became his real field of expertise. Although he did not conduct any field research of his own, he was very active in the areas of acquisition, research, and publication. The museum benefited in particular from his acquisition of objects from Benin, among other places, and his efforts to build up the phonogram archive. In 1909, he was appointed Professor of Anthropology at the University of Berlin.

Die anthropologischen Sammlungen am Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte

In 2011, the SPK took over the "Felix von Luschan" university anthropological collection and the associated anthropological-osteological collections from the Charité. Felix von Luschan’s so-called S-collection was built up roughly between 1885 and 1920. It originally comprised around 6,300 skulls. Among the associated collections are the RSK-collection and the K-collection as well as a smaller number of bones that cannot yet be assigned definitively to any collection.

SPK policy on dealing with human remains

The collections of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin contain human remains of various kinds. They can be classified as archaeological finds, ethnological objects (such as those made partly of hair, for example), or anthropological objects. Museums should deal with any such human remains in a particularly sensitive way and must observe high ethical and moral standards. The policy is based on the recommendations made by the German Museums Association. In addition, the SPK has developed its own set of guidelines.