In 2021, a project was launched to investigate the origins of human remains from West Africa. During the second half of May, participating researchers from six African countries and Germany gathered for a conference in Yaoundé, Cameroon. With two-thirds of the time allotted to the project having elapsed, the international team of investigators presented and discussed results from Berlin as well as the provenance and field research conducted in Cameroon and Togo and developed ideas for follow-up projects.

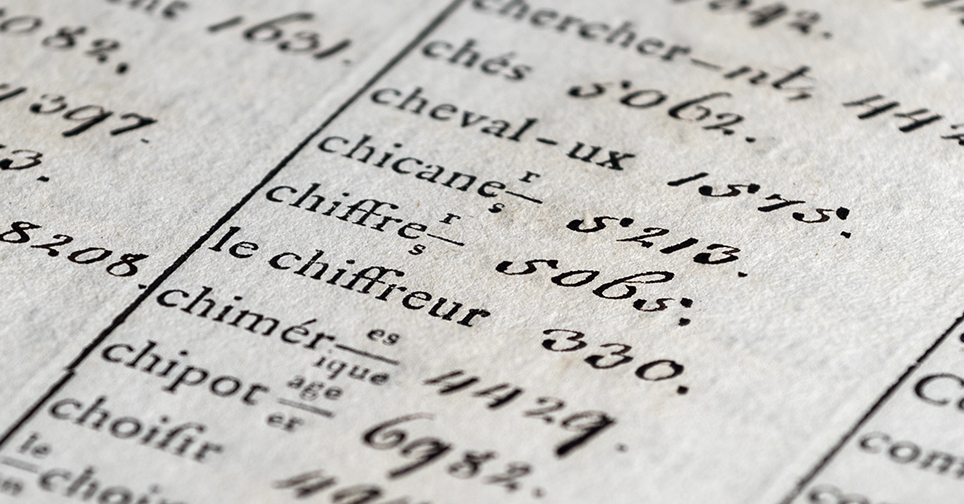

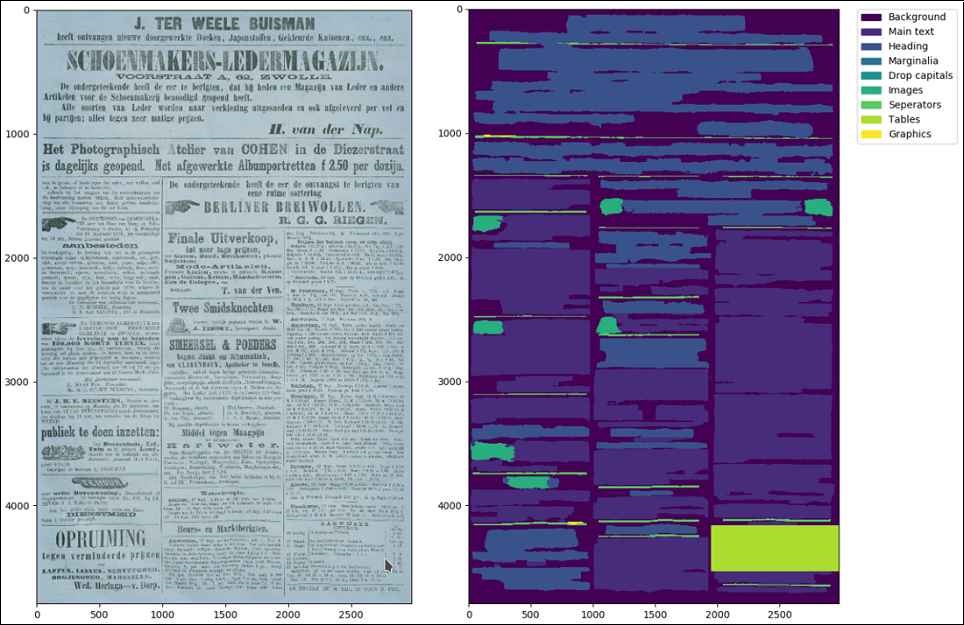

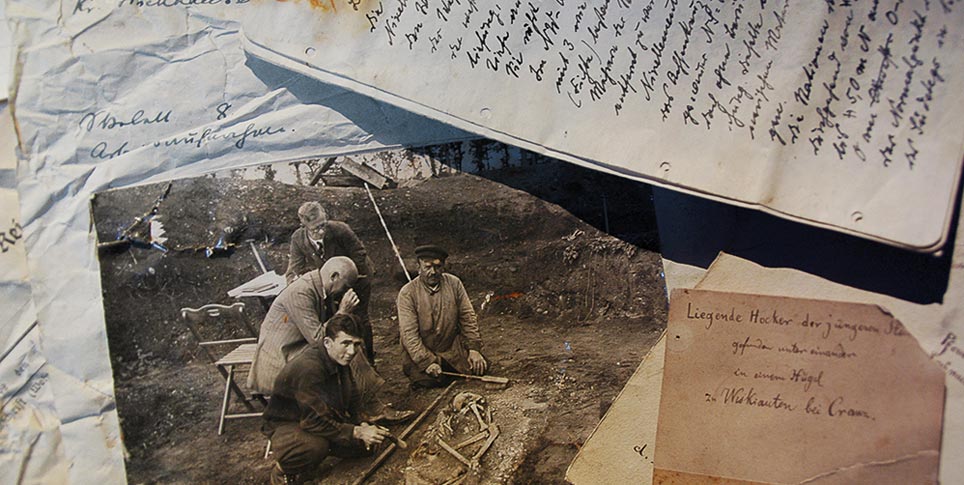

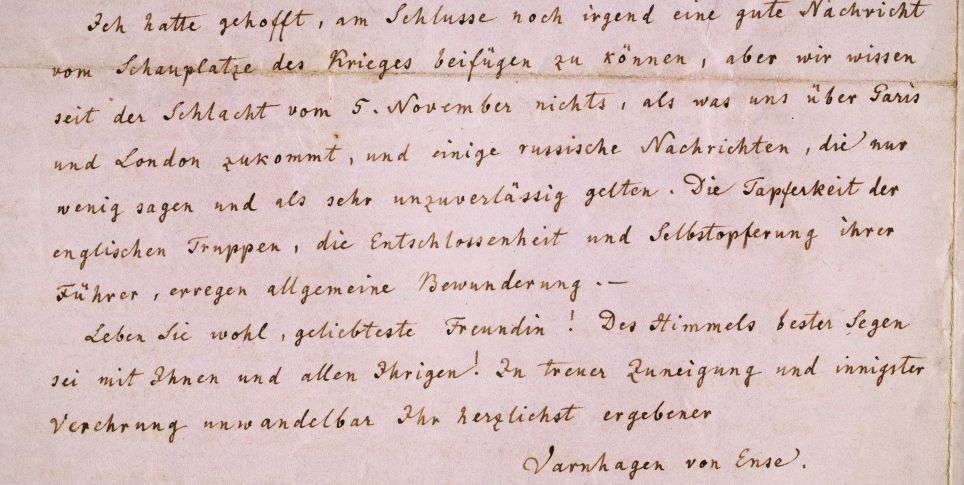

“Since the methodology used in the preceding project on East Africa proved to be successful, this one likewise involves archival research, anthropological investigations in cases where the local provenance is unclear, and above all an effort to capture the voices of the communities of origin,” says Dr. Bernhard Heeb, collection manager at the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte (Museum of Prehistory and Early History) and project coordinator. “So our Cameroonian and Togolese colleagues traveled the countries involved and established contact with local communities.” The Berlin team, which consists of ethnologist Marius Kowalak, anthropologist Barbara Teßmann and archeologist Bernhard Heeb, is in constant contact with project partners Professor David Simo (Université de Yaoundé II) and Professor Kokou Azamede (Université de Lomé). On the German side, the focus is on examining written sources (archives, literature and bequests) and conducting dedicated anthropological investigations, which often supplement and complement the results from Togo and Cameroon in important ways. Everyone on the project shares a common goal: to learn where the remains came from and how they were acquired so that they can be returned to the communities in question.

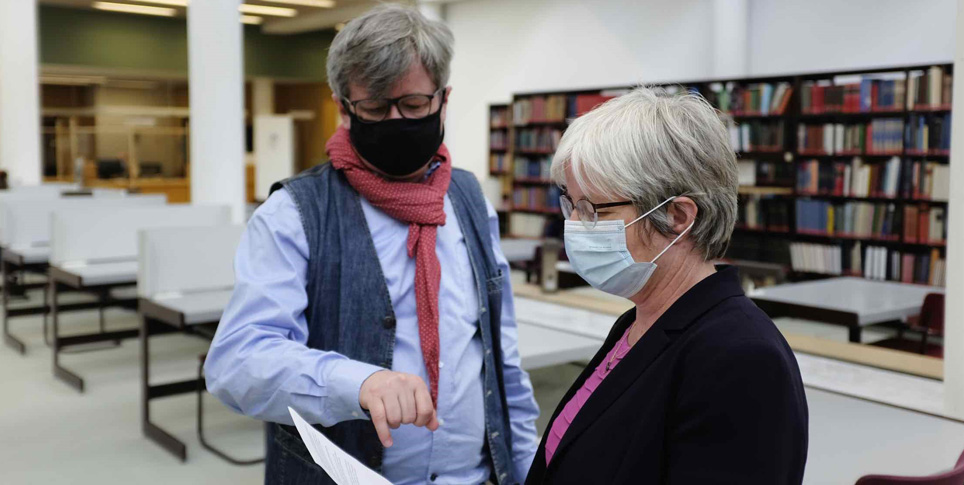

V.l.n.r: Bernhard Heeb (Kustos am Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte), Kokou Azamede (Université de Lomé) und David Simo (Université de Yaoundé II). Foto: © SPK / Stefan Müchler

“One thing that the team noticed repeatedly over the course of field research in the local communities in Togo and Cameroon is that the connection people feel to their ancestors – whose remains are in Berlin – is much stronger than we initially expected it would be,” says Heeb. “Even though there is often no memory of these remains being taken, the people are still unsettled to learn what occurred. Almost without exception, they called for their return and at the same time presented ideas for how the remains could be re-personalized and ceremonially reincorporated into the community.”

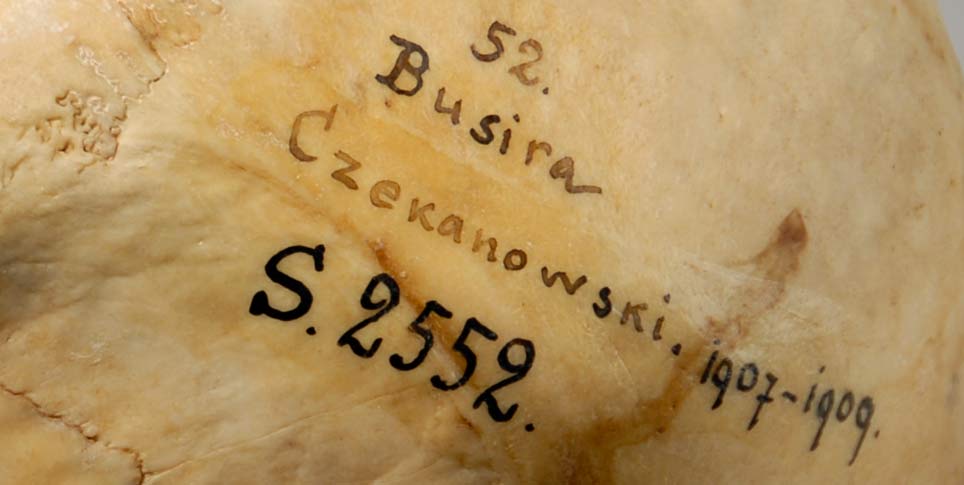

The skulls that were taken from West Africa are part of the anthropological collections that the SPK took over from the Charité university hospital in 2011. These include approximately 7,700 pieces of human remains that were amassed from across the world during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. About a third of them come from former German colonies in Africa and the Pacific. In a pilot project that ran from 2017 to 2019, researchers investigated the origin of 1135 human skulls from the former colony of German East Africa. The experience that was gained there served as the basis for the current project, which is primarily examining remains from Cameroon and Togo. The objective of the research is to work with scientists from the countries of origin to recontextualize the 477 human skulls taken to Berlin during the colonial era so that they can be returned to those countries. The project is receiving funding of approximately 715,000 euros from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and the Media.

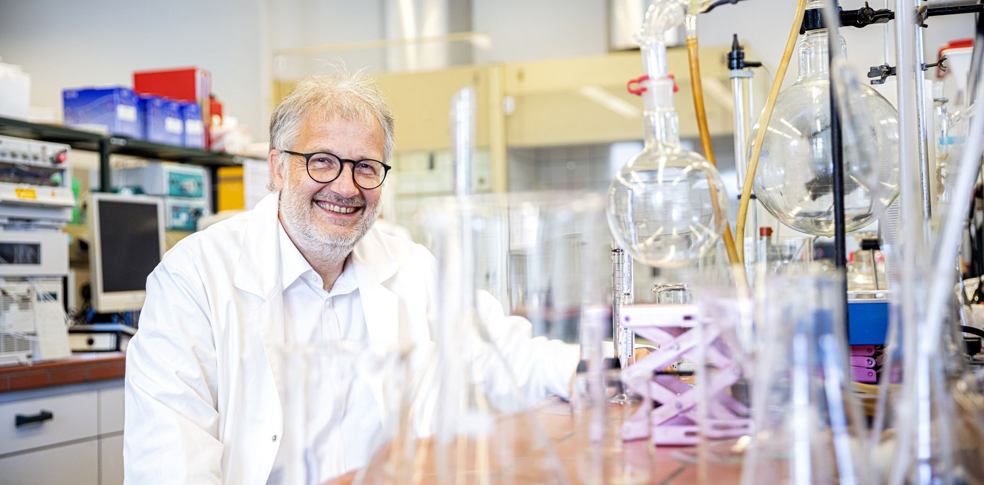

Round Table zu Erfahrungsberichten aus verschiedenen afrikanischen Ländern während des wissenschaftlichen Workshops im Nationalmuseum von Kamerun zur Provenienzforschung an menschlichen Überresten aus Kamerun und Togo in Yaoundé mit (v.l.n.r.) Kokou Azamede (Université de Lomé), Vilho Amukwaya Shigwedha (Universität von Namibia, Windhoek), Andreas Winkelmann (Medizinische Hochschule Brandenburg, Neuruppin) und Albert Gouaffo (Université de Dschang, Kamerun). Foto: © SPK / Stefan Müchler

Based on the provenance research conducted in Berlin and Togo, Professor Kokou Azamede was able to identify the places from which the skulls were said to have been taken and locate them on maps. Equipped with this information, Azamede and his team established direct contact with individual communities and conducted research locally. “Typically, at the initial meeting with us, the local chief would gather the people he worked with and the elders around him,” says Azamede. “First, we would talk with people about their memories of German colonial rule and then tell them that human remains from these regions were still being kept in Berlin. In a third step, we then asked the community to share their opinions and preferences regarding the bones.” Many communities, Azamede explains, were very surprised and initially shocked to learn, more than a hundred years later, that skulls of their forebears were taken to Germany. In general, however, the initial outrage that they felt quickly gave way to great interest.

Azamede and his team promised that, when the research was completed, they would return to the village communities to share the results. “People feel they have a duty to honor their ancestors,” he says. “As long as their ancestors aren’t properly laid to rest, there won’t be peace in the region – that’s something we heard again and again.” In addition to the knowledge gained about the origin of these remains and the period in which they were taken, the project therefore also offers a unique opportunity to promote goodwill among peoples and heal the wounds of the past.