Hanna Strzoda, provenance researcher in a project examining acquisitions for the “Sammlung der Zeichnungen” made between 1933 and 1945, and Anna Pfäfflin, curator for 19th-century art in the Kupferstichkabinett, describe the typical problems they encounter researching the origins of works on paper. They will participate this year in a German-American exchange program for provenance researchers.

What exactly is the „Sammlung der Zeichnungen” (Collection of Drawings)?

Anna Pfäfflin: In the late 19th century, the then Nationalgalerie (National Gallery) was created as a museum for contemporary art. It was intended to hold works created in a variety of media, i.e., paintings, sculptures, drawings and, initially, prints as well. The Kupferstichkabinett (Museum of Prints and Drawings), which had been created several decades earlier, possessed a collection of what were then contemporary drawings and part of these were consequently moved to the Nationalgalerie. When Germany was divided after the Second World War, its museums were divided, as well, with the East and the West maintaining (and adding to) a “Sammlung der Zeichnungen” of their own. Both sides gave some thought to where the collections should be housed. In East Berlin, the collection remained in the Nationalgalerie until 1968; from 1969 to 1984, it was part of the East Berlin Kupferstichkabinett; in 1984, it was returned to the Nationalgalerie, where it stayed until 1992. The West, too, initially kept the collection in their Nationalgalerie. In 1986, it was moved to the Kupferstichkabinett. In 1992, in the wake of reunification, the two collections were merged and the reunited “Sammlung der Zeichnungen” was housed in the Kupferstichkabinett at the Kulturforum.

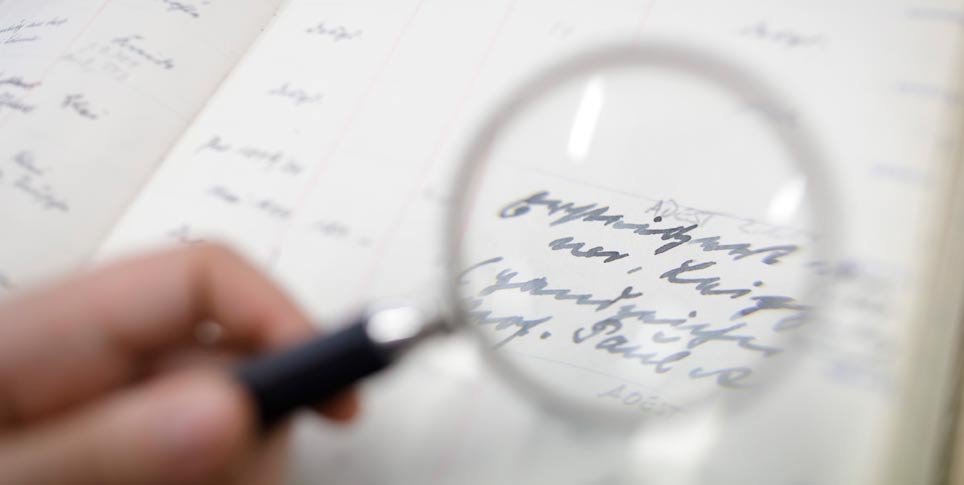

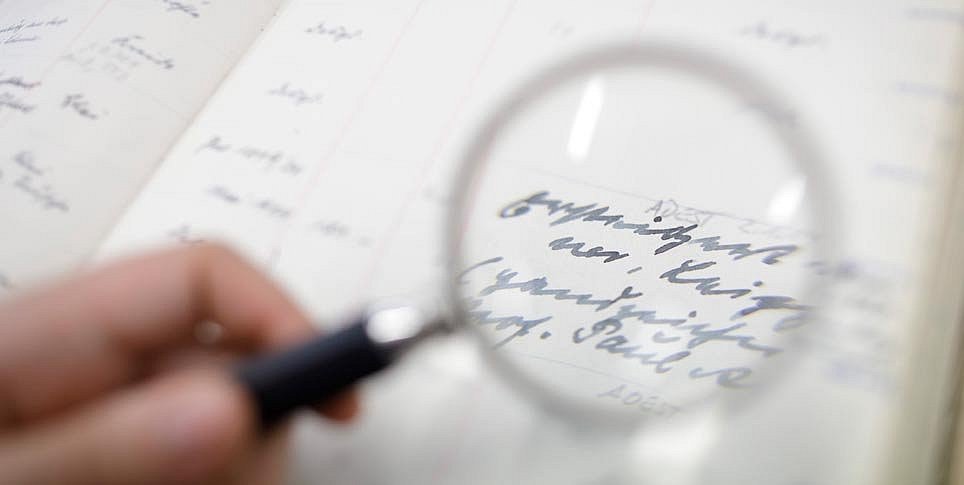

Die Lupe zeigt es: Kleins Werk wurde „ersteigert bei C. G. Boerner, Leipzig, 16.5.1934 (Handzeichnungssammlung Prof. Paul Arndt, München)“ © SPK / photothek.net / Thomas Koehler

How large is the collection?

It contains approximately 50,000 works.

And is provenance research being done on all of them?

Hanna Strzoda: No, for this project I’m only looking at acquisitions made between 1933 and 1945. That amounts to about 1,200 works. In the first phase of the project, that number was reduced still further. First, I checked to see what was actually there, as some pieces had been lost in the war and purged during the Degenerate Art operation. Then I dismissed any works purchased directly from regime-conformist artists, as these works would, of course, not have been seized from their owners as a result of Nazi persecution. That left a total of about 950 different works that needed to be investigated.

Where do you start when you have 950 works? With the lowest inventory number?

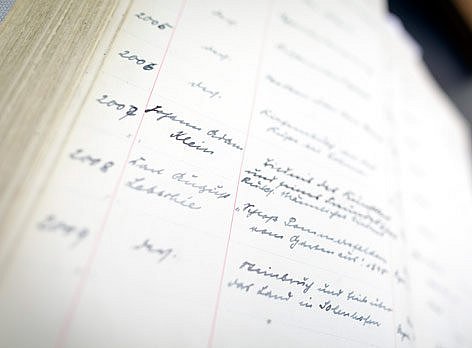

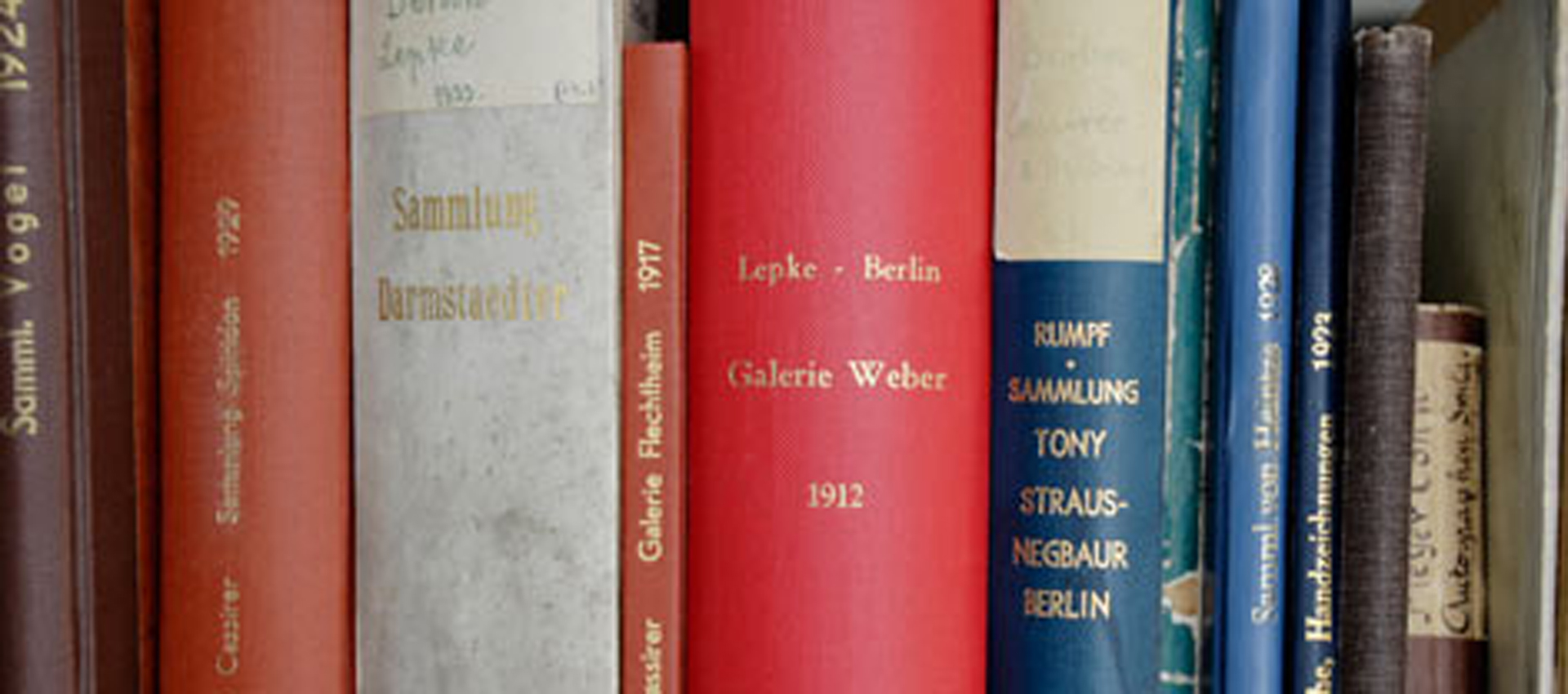

HS: I actually did work my way through the inventory, starting with the first inventory number of 1933 and then working my way up subsequent years. The first thing I did was gather all the information about previous owners from the inventory and compare it with the index cards, provided they were still extant. I also checked the back of every single work and noted any distinguishing marks that would help determine its provenance – things like collector marks, labels, auction lot numbers. In other words, everything that I could do here in the museum. Then I looked through the acquisition records in the Zentralarchiv (Central Archive) of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (National Museums in Berlin). Fortunately, because the collection belonged to the Nationalgalerie at the time, an unusually large number of files has survived.

Why is that so unusual? Don’t museums always document their acquisitions?

HS: Yes, they do, and they did that then, too, of course, but a lot of files were lost in the war. Most of the Kupferstichkabinett files, for example, were lost in the war. It's just a happy accident that the files of the Nationalgalerie survived.

AP: In general, documentation is worse for drawings than for paintings, as they are commercially less valuable and several were often bought at a time. The record might say something like “5 drawings by Liebermann, of which 3 are landscapes and 2 still lifes.”

HS: But here, too, the Nationalgalerie proves the exception to the rule. The curators there were used to dealing with paintings. They gave every single drawing the same amount of attention, and so each of them has its own inventory number.

How do you proceed from there? Does this information reveal the history of each work? That doesn’t sound very exciting.

HS: Only very rarely does this information uncover the history of the work. It just gives you clues. When you find a collector’s mark, for example, the first question is whether you can even identify it. I’m in constant contact with the people who maintain the Lugt database, a database for collector's marks. Some objects were acquired from private individuals, in which case you might find correspondence with the previous owner regarding the purchase and some mention of where the object is from. More than half of the works were purchased from professional art dealers, however. In those cases, the only information you find in the inventory book or card index is the name of the dealer – a gallery, perhaps, or an auction house. You still don’t know, though, who the previous owner was, in other words, the person who gave it to the dealer to sell or who delivered it to the auction house. And that's when the real work begins.

This kind of extensive research takes a lot of time, sometimes weeks or months

AP: And that, of course, is also the difficulty for me as a curator. It's relatively easy to take these first few steps – check the inventory book, the card index, the object – but digging deeper into provenance takes much more time, of course.

What do you do with all the clues?

HS: You put together a well-structured record of all the information you’ve collected on the work. Ideally, it gives you the complete provenance, but that doesn’t happen very often. Then you search further. There are archives on certain art dealerships, such as the Ferdinand Möller Archive in the Berlinische Galerie. Sometimes you can ascertain the previous owner from business documents, and the search is concluded with relatively little time and effort having gone into it.

And how do you find out who consigned a picture when there isn't an archive?

HS: That is a huge issue. I’ve spent so much time on it over the past three years that it’s almost become a hobby. In 1934, the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts decreed that auctions had to be registered with the Reich Chamber and that the person who delivered the item had to be listed in code in the auction catalog. When you open up an auction catalog from the Nazi period, you see cryptic notations such as “S. in B.” or “Property VIX” or just initials that sometimes appear to just be initials. “G.St.” – I recently came across that one and it turned out it stands for the district attorney (Generalstaatsanwalt). It's a good example of how initials were sometimes used to deliberately conceal the owner's Jewish origins. If you’re lucky, the auction registration information is still extant. When registering the auction with the Reich Chamber, the name of the consignor had to be given, along with their address and the objects being delivered. If I’m lucky enough to get this far, then I’ve made quite a lot of progress. Often, though, you don't get that lucky.

And what happens then?

HS: Then you look elsewhere – let’s say the object we’re interested in was consigned along with other items. Then you can examine documents concerning the consignment as a whole, look into other items that were not acquired by our museum but were in the same lot, and see if perhaps you can find their previous owners. One thing is clear, though. A good third of the works I’ve examined in the Kupferstichkabinett were acquired at auctions. That means that we’re looking at a good 300 different ownership initials. And that is just one of many answers to a question that we are asked again and again: Why does provenance research take so long?

Why is that so unusual? Don’t museums always document their acquisitions?

HS: Yes, they do, and they did that then, too, of course, but a lot of files were lost in the war. Most of the Kupferstichkabinett files, for example, were lost in the war. It's just a happy accident that the files of the Nationalgalerie survived.

AP: In general, documentation is worse for drawings than for paintings, as they are commercially less valuable and several were often bought at a time. The record might say something like “5 drawings by Liebermann, of which 3 are landscapes and 2 still lifes.”

HS: But here, too, the Nationalgalerie proves the exception to the rule. The curators there were used to dealing with paintings. They gave every single drawing the same amount of attention, and so each of them has its own inventory number.

How do you proceed from there? Does this information reveal the history of each work? That doesn’t sound very exciting.

HS: Only very rarely does this information uncover the history of the work. It just gives you clues. When you find a collector’s mark, for example, the first question is whether you can even identify it. I’m in constant contact with the people who maintain the Lugt database, a database for collector's marks. Some objects were acquired from private individuals, in which case you might find correspondence with the previous owner regarding the purchase and some mention of where the object is from. More than half of the works were purchased from professional art dealers, however. In those cases, the only information you find in the inventory book or card index is the name of the dealer – a gallery, perhaps, or an auction house. You still don’t know, though, who the previous owner was, in other words, the person who gave it to the dealer to sell or who delivered it to the auction house. And that's when the real work begins.

This kind of extensive research takes a lot of time, sometimes weeks or months

AP: And that, of course, is also the difficulty for me as a curator. It's relatively easy to take these first few steps – check the inventory book, the card index, the object – but digging deeper into provenance takes much more time, of course.

What do you do with all the clues?

HS: You put together a well-structured record of all the information you’ve collected on the work. Ideally, it gives you the complete provenance, but that doesn’t happen very often. Then you search further. There are archives on certain art dealerships, such as the Ferdinand Möller Archive in the Berlinische Galerie. Sometimes you can ascertain the previous owner from business documents, and the search is concluded with relatively little time and effort having gone into it.

And how do you find out who consigned a picture when there isn't an archive?

HS: That is a huge issue. I’ve spent so much time on it over the past three years that it’s almost become a hobby. In 1934, the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts decreed that auctions had to be registered with the Reich Chamber and that the person who delivered the item had to be listed in code in the auction catalog. When you open up an auction catalog from the Nazi period, you see cryptic notations such as “S. in B.” or “Property VIX” or just initials that sometimes appear to just be initials. “G.St.” – I recently came across that one and it turned out it stands for the district attorney (Generalstaatsanwalt). It's a good example of how initials were sometimes used to deliberately conceal the owner's Jewish origins. If you’re lucky, the auction registration information is still extant. When registering the auction with the Reich Chamber, the name of the consignor had to be given, along with their address and the objects being delivered. If I’m lucky enough to get this far, then I’ve made quite a lot of progress. Often, though, you don't get that lucky.

And what happens then?

HS: Then you look elsewhere – let’s say the object we’re interested in was consigned along with other items. Then you can examine documents concerning the consignment as a whole, look into other items that were not acquired by our museum but were in the same lot, and see if perhaps you can find their previous owners. One thing is clear, though. A good third of the works I’ve examined in the Kupferstichkabinett were acquired at auctions. That means that we’re looking at a good 300 different ownership initials. And that is just one of many answers to a question that we are asked again and again: Why does provenance research take so long?

Is it always possible to uncover the history of a work?

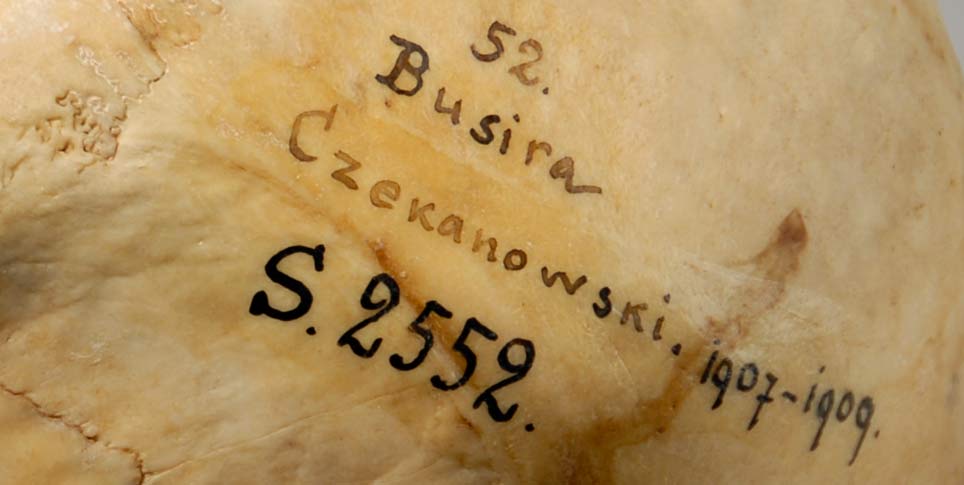

HS: Sadly, in the case of works acquired through art dealers, gaps often remain. This is especially true of works on paper, since you’re investigating works whose identity is sometimes unclear. When drawings are called “Standing man,” “Sitting nude,” or “Landscape,” it is extraordinarily difficult to clearly establish their identity. In auction catalogs, a high-priced painting may be listed with half a page of description and a copy of the work, while an inexpensive drawing is given just three short lines of text detailing the most basic information and is generally unaccompanied by a picture. A further difficulty affecting prints is that for a single work, there are always multiple copies.

AP: And because drawings are often priced lower, they were – and are – purchased by people who may not be very well known as collectors, people who aren't “big names.”

HS: Exactly, and then you have to look into their life stories, your aim being, of course, to find out whether this previous owner may have been a member of a persecuted group, what religion they practiced, whether they were politically active – in other words, what kind of person were they? This is the only way to assess whether an acquisition might have been seized by the Nazis as part of their policies of persecution. And then we begin to dig deeper, in external archives. If the previous owners lived in Berlin, I generally make inquiries at the Berlin State Archive, the German Federal Archives, the Compensation Office, and the Central State Archive of Brandenburg, where the police headquarters files – that is, the actual records of seizure – are kept. In this way, I try to reconstruct the immediate circumstances around the act of persecution. This kind of extensive research takes a lot of time, sometimes weeks or months.

But still, it's crucial that we know where the work comes from before we add it to the collection. Anna Pfäfflin

That long for a single work?

HS: Absolutely, especially when you consider that it may take four to six weeks before the archive answers a request for information. And when you’re doing research on someone who isn’t from Berlin, the challenge is even greater. Which archives have the files that I need? And how do I gain access to the files? I can often order a copy if the archive is able to give me the file signature but sometimes I have to go there in person and look for myself. In the end, there are a lot of different puzzle pieces, collected from sometimes as many as thirty different files, which themselves may come from ten different archives.

AP: Of course, today, when we acquire artworks, we have to do this kind of research in advance. It’s difficult and delicate work sometimes, especially when you’re dealing with private individuals who want to make a donation. They might have inherited the piece from their parents and know nothing of its previous history. So, when we begin to ask questions, a lot of tact and sensitivity is required. But still, it's crucial that we know where the work comes from before we add it to the collection. That is part of our responsibility as curators, and is not the job of provenance researchers, who work on projects to examine previous acquisitions, either specific objects or entire collections.

How often does your research require you to leave Berlin?

HS: In the particular case of the “Sammlung der Zeichnungen”, quite a lot of the collection was actually acquired in Berlin. This allows us to do most of the research locally. It’s still important, however, to see the bigger picture and look beyond your own city. Take the problem with the auction initials, for example – we would never get anywhere if we didn’t collaborate very closely with fellow researchers. Imagine an owner consigns 200 works, all of which are registered under the same ownership initials. Of these 200 works, however, some go to Vienna, others to Düsseldorf, a few to Berlin, etc. etc. The information is just as widely dispersed as the works themselves. The only way to get good results is to work with people in these various cities. In another project examining post-war acquisitions, we worked much more closely with the U.S. because of the possibility that works which left Germany during the period of Nazi rule and ended up on the American art market were later sold back to Germany. That is why we see the networks that are being formed through the extensive exchange program PREP as a big opportunity.

The project in the Kupferstichkabinett is slowly coming to an end. How many pieces have you found that will have to be returned?

HS: For around half of the works, we were able to rule out any suspicion that they were confiscated as a result of Nazi persecution, either through a complete provenance or one that raised no doubts whatsoever. For a handful of works, we’re now going to have to check if and to whom restitution can be made. But in the end, in all collections of works on paper, there always remains a large number of works whose provenance cannot be established – you reach a certain point where you cannot go any further, and you presumably never will. That’s the case here, too. On the other hand – and we need to be very clear about this – there are no grounds to believe these works were seized by the Nazis as part of their policies of persecution.

Will the results of your work be published?

HS: They won't be published as a book, but we are putting them online, bit by bit, on the SMB Digital website. Once the project has been completed, all the provenance chains that we were able to establish will available there for anyone to read.

Originally this article was published in the blog of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung

The Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung is the largest nonuniversity research center for musicology in Germany. It is dedicated to historical and theoretical reflection on music and making it accessible to a wider public. In its Musikinstrumenten-Museum it collects instruments of the European classical music tradition from the 16th to the 21th century. Founded as early as 1888, the museum contains over 3.000 historical instruments and provides an ideal forum for hosting various events, from academic symposia to lecture recitals with Early Music performances on period instruments of the museum’s collection to interactive sound installations. .

Voice Republic

Wie können Provenienzforscher herausfinden, ob ein Kunstwerk zur NS-Zeit unrechtmäßig den Besitzer gewechselt hat? Am 27. September 2017 berichten Teilnehmer des Austauschprogramms PREP in einer öffentlichen Abendveranstaltungen von Herausforderungen und Erfolgen ihrer Arbeit. Die Vorträge finden in deutscher und englischer Sprache statt.