Friederike Seyfried, director of the Ägyptisches Museum, discusses the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa North, paintings of captivating beauty, and the puzzle of broken shards.

Ms. Seyfried, the tombs that you and your team are uncovering near Aswan, on the banks of the Nile, are more than three thousand years old but were only discovered a little over ten years ago. Does it surprise you that so many treasures of Ancient Egypt still lie hidden in the sands?

No. We believe that well over a third of the material remains from this period are still unexcavated. The dry desert sand protects them. This is very fortunate as far as the objects are concerned, and it means that there are good prospects for learning new things.

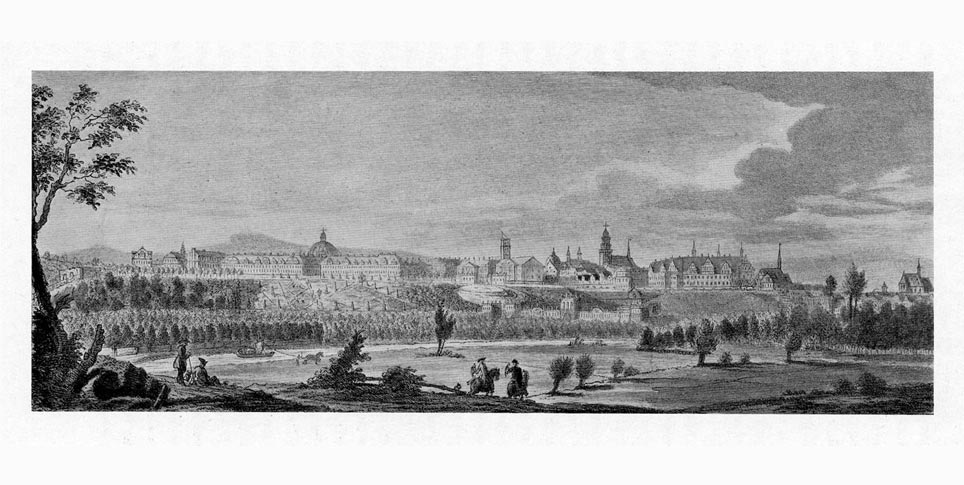

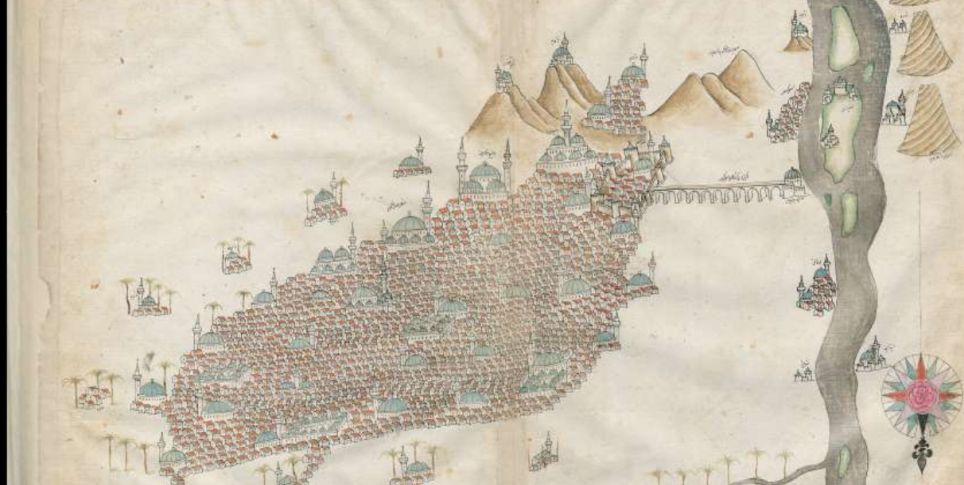

The necropolis you’re working on is called Qubbet el-Hawa North. It’s located about 800 meters north of the well-known burial site of Qubbet el-Hawa. How was it found?

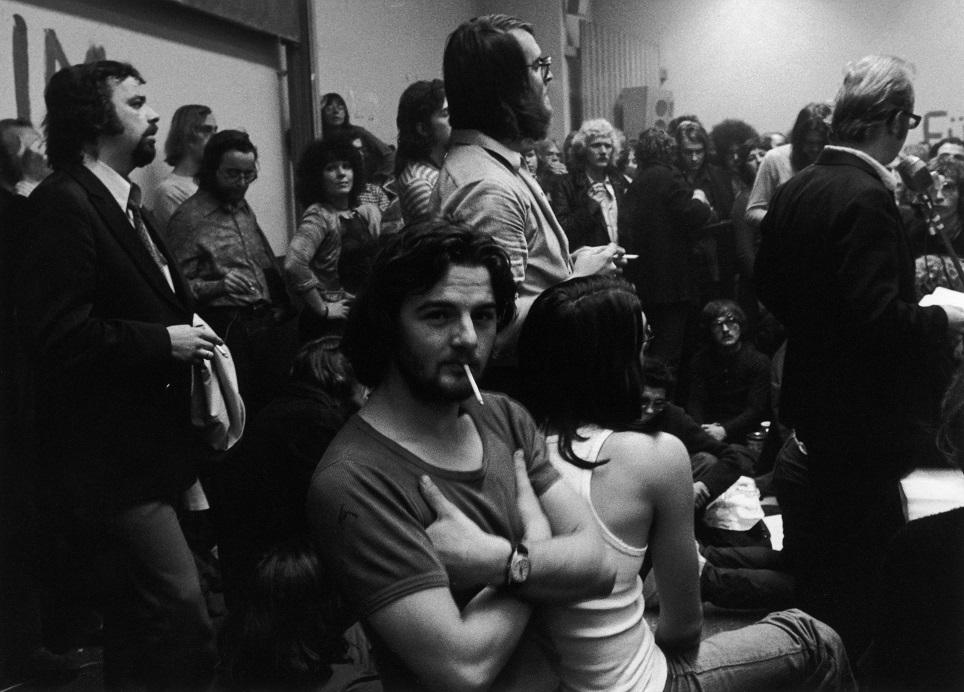

It was during the troubled times of the “Arab Spring,” between 2011 and 2013, when the police presence in the area was not very strong. Some residents of Gharb-Aswan took this opportunity to expand their village, and when they stumbled on some rock-cut tombs that had probably been undisturbed up until that point, they looted them systematically. This was done on a grand scale and with mafia-like structures. Many of the items were probably taken with the intention of selling them on the international art market. And some of the thieves are undoubtedly still waiting for the chance to make money off the spoils.

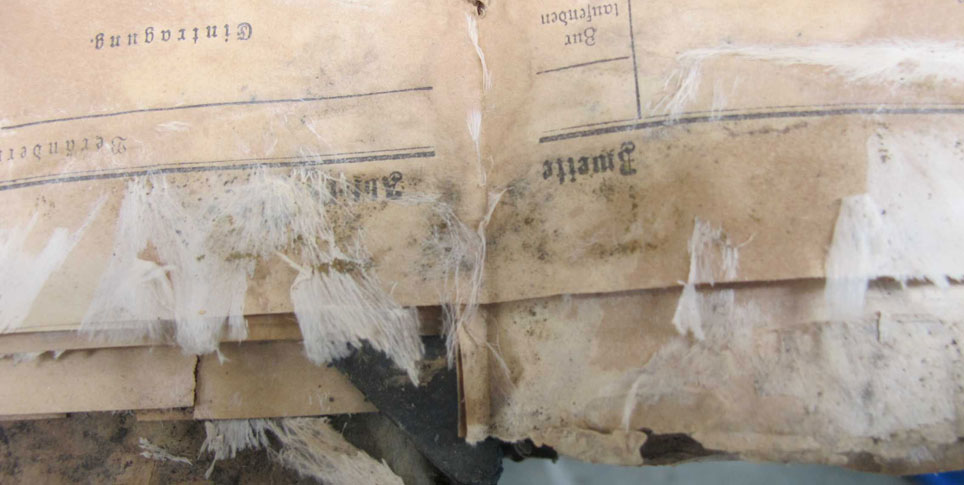

The robbers used heavy equipment, excavators and jackhammers. In the process, a very beautiful architrave decorated with colored hieroglyphs was knocked out of one of the tombs, causing considerable damage.

That’s terrible...

Yes, but the very dedicated young Egyptian staff of the local inspectorate soon put an end to these misdeeds. They installed sturdy iron doors in front of the tomb entrances, secured some of the objects, and moved them to the state antiquities depository.

How did you and your team come to work on the project?

The Egyptian Minister of Antiquities at the time, Mohamed Ibrahim Ali, was at the ITB in Berlin and conducted talks with SPK President Hermann Parzinger and me. He suggested we form a partnership and asked us if the SPK could support Egyptian experts in protecting and excavating Qubbet el-Hawa North. We were happy to accept. This dig is a dream for us. It gives us new and unique insights into the structure of the New Kingdom’s highest elite at the southernmost end of what was then the Egyptian heartland.

You have a lot of experience.

Yes, I have been documenting tombs of this era for over twenty-five years. But the project is also of great importance for the Ägyptisches Museum (Egyptian Museum). It is the first time since 1914 – that is, since Ludwig Borchardt’s excavations in Tell el-Amarna – that we have been able to dig in this area, the place central to our research. That’s why we’re so happy about this partnership and so grateful to be able to be on site so regularly now.

There’s quite a lot of sand there...

There certainly is. We’re concentrating on excavating and documenting nine previously unknown rock-cut tombs. The sands have swept over these tombs – and the forecourts in particular – covering them or at least filling them in. Then there’s what was dug out by the looters. This sand has to be carried away by hand. But as Egyptologists, we’re used to this. We have a lot of local helpers who take care of this hard work. They sift through the sand and debris to recover even the smallest artifacts – everything the tomb robbers left behind.

Are you all settled in now?

We’ve rented a place to stay in the village where we can also store our equipment. We typically start to dig in the morning, around 6:00. Everybody prepares their own breakfast and mid-day snack, then we drive a rented pickup to the site, where we stay until 2:00 p.m. at the latest. After that, it’s just too hot – and the official Egyptian workday ends at 2:00 as well. In the afternoon, we work at our desks. We assess our finds, work on the computer. It sounds demanding, but we really enjoy it.

What did the thieves leave behind?

Unfortunately, they really helped themselves. The most valuable things have disappeared. But some smaller objects are still there, amulets and little statuettes representing the dead, pieces of splintered-off wood from coffins and boxes. Mostly, we find a lot of broken pottery, which the robbers weren’t interested in.

What are the highlights so far?

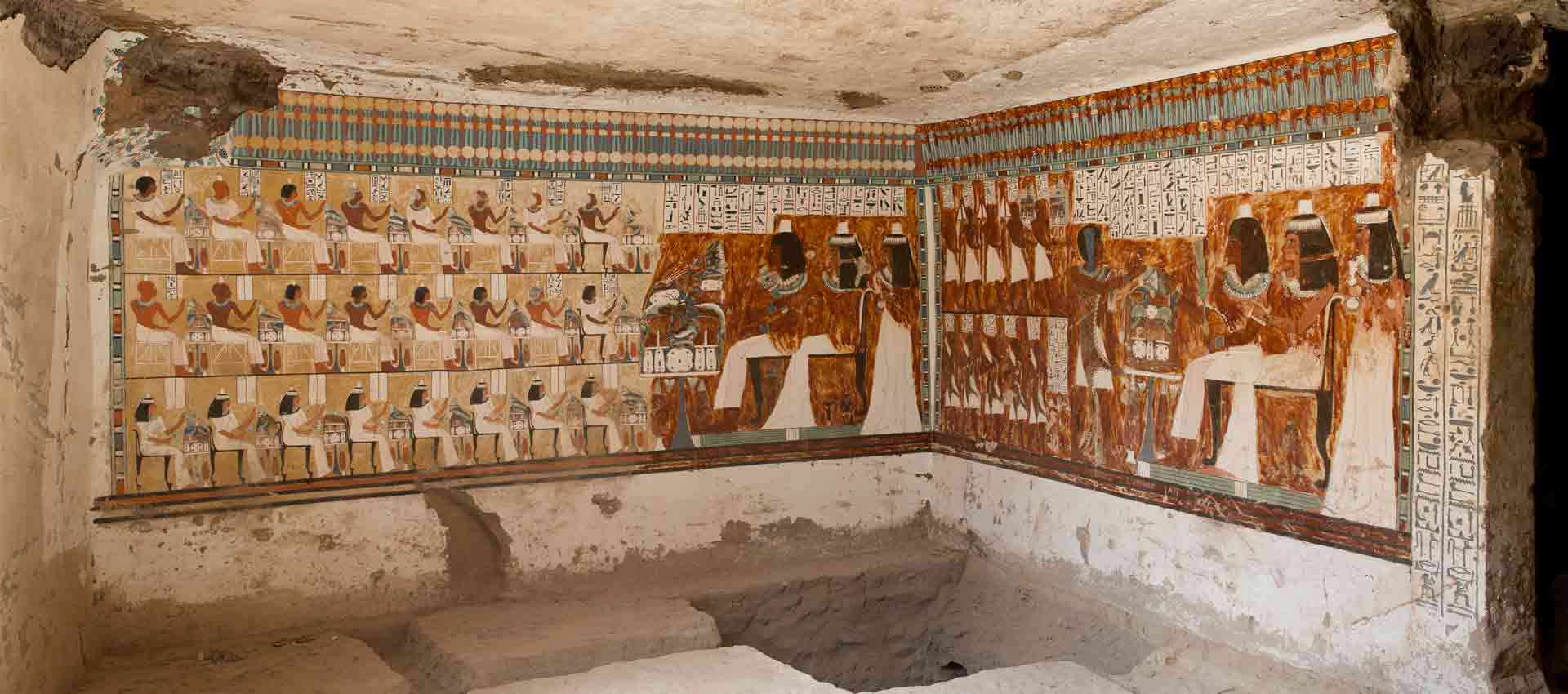

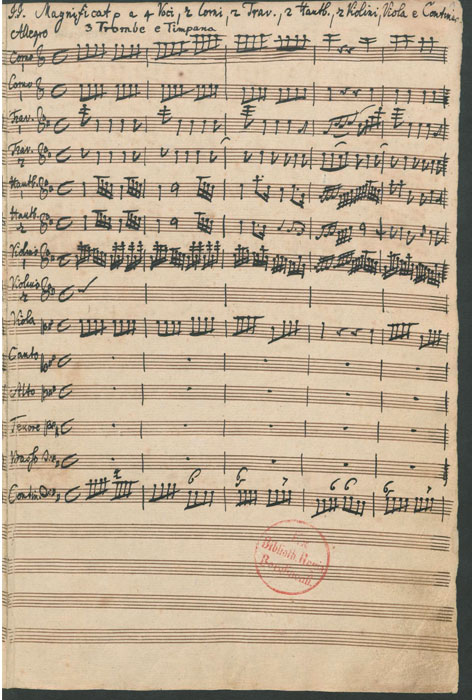

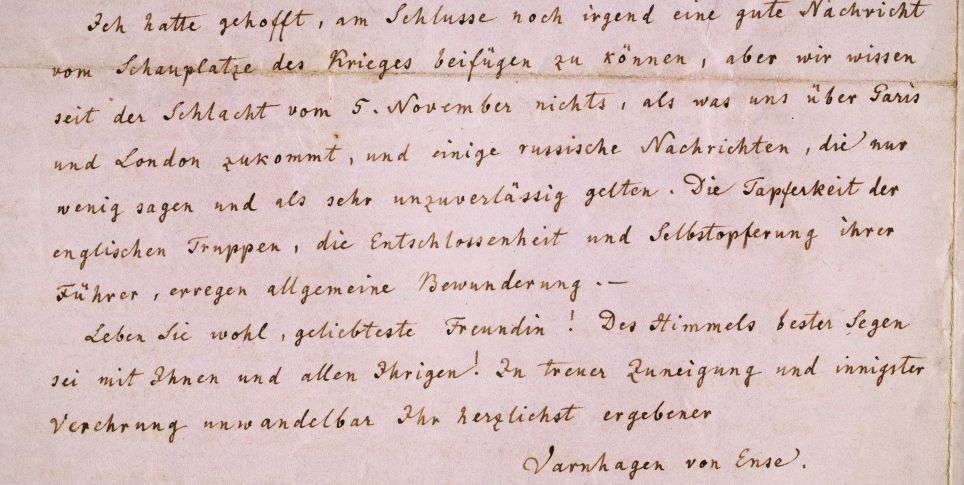

One tomb in particular stands out, that of the “mayor” of Elephantine, a man named User. The tomb was built around 1360 BC in the reign of Amenhotep III. It’s been designated “QHN 2” in our records; this stands for Qubbet el-Hawa North, Tomb 2. It is decorated with exceptionally lavish wall paintings showing the tomb owner with his friends and relatives celebrating the New Year. The depiction of elderly banquet guests is particularly unusual, as they are shown with gray or white hair and partially bald. Equally notable is the fact that these scenes show not only relatively fair-skinned Egyptians but also their dark-skinned work colleagues, people of different ethnicities who were nevertheless very clearly Egyptian citizens. The details of these paintings are just breathtakingly beautiful.

How exactly do you approach your work?

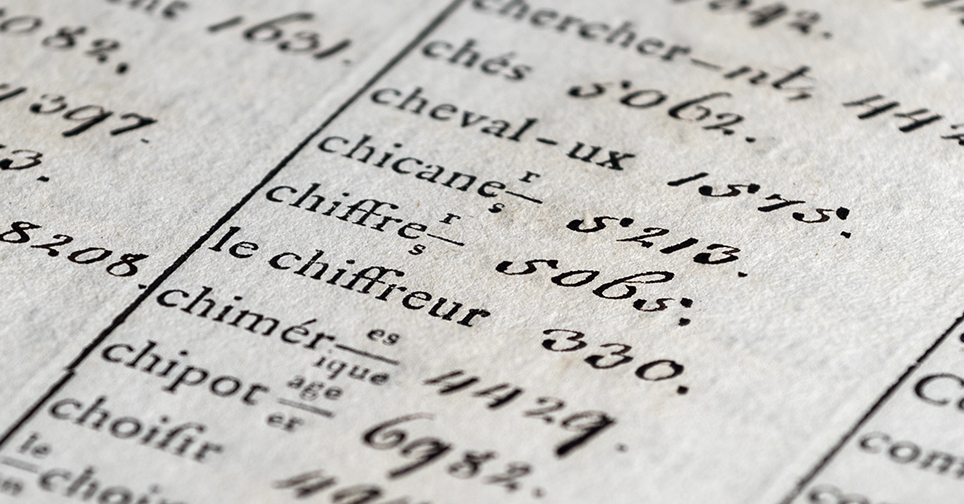

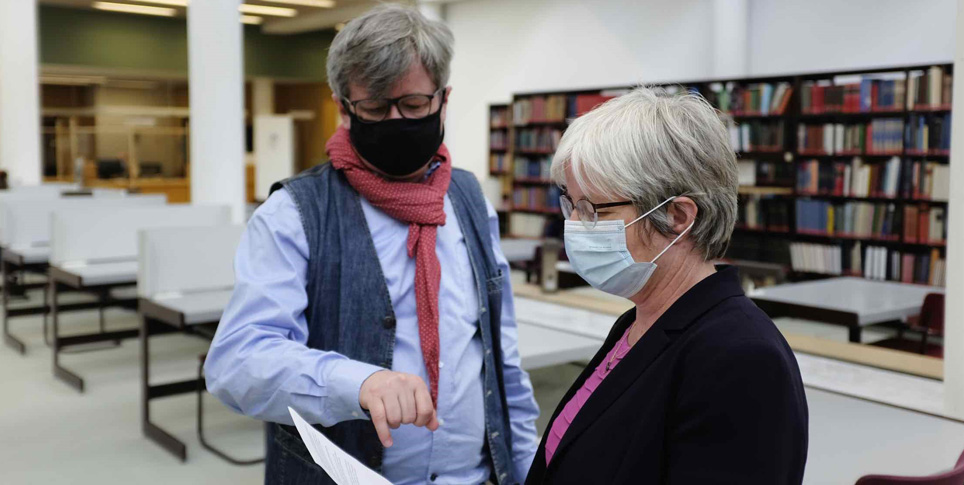

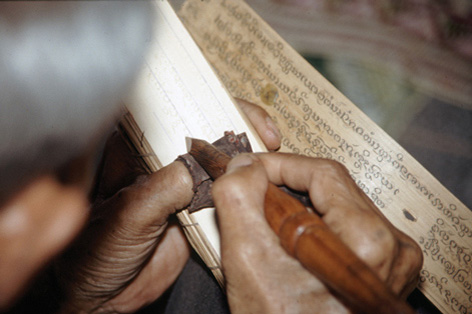

Well, in User’s tomb there are also papyrus fragments. They were part of a book of the dead that belonged to the lady of the house, a woman by the name of Tuju. These fragments are tended to by Myriam Krutzsch, our papyrus conservator, who has actually been in retirement for some time now. It’s a wonderful project, financed by donations from the board of the Friends of the Egyptian Museum Berlin. Ms. Krutzsch is the leading expert in her field. She is also training local women to be conservators, in keeping with the spirit of our partnership. They take the fragments one by one, smooth them out, match the pieces, and reassemble them – it is painstaking work. We hope to be able to treat the papyrus in such a way that it can one day be exhibited in the Nubian Museum (in Aswan).

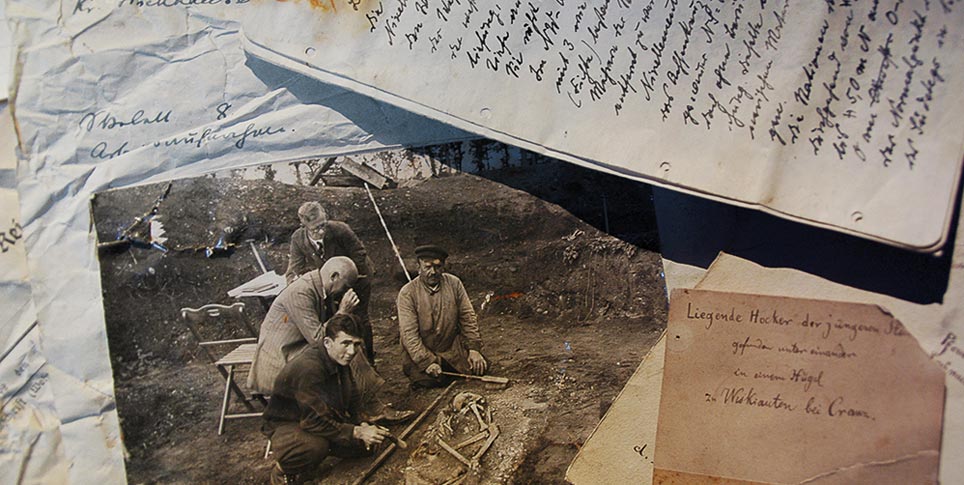

Don’t archeologists work mostly with broken shards?

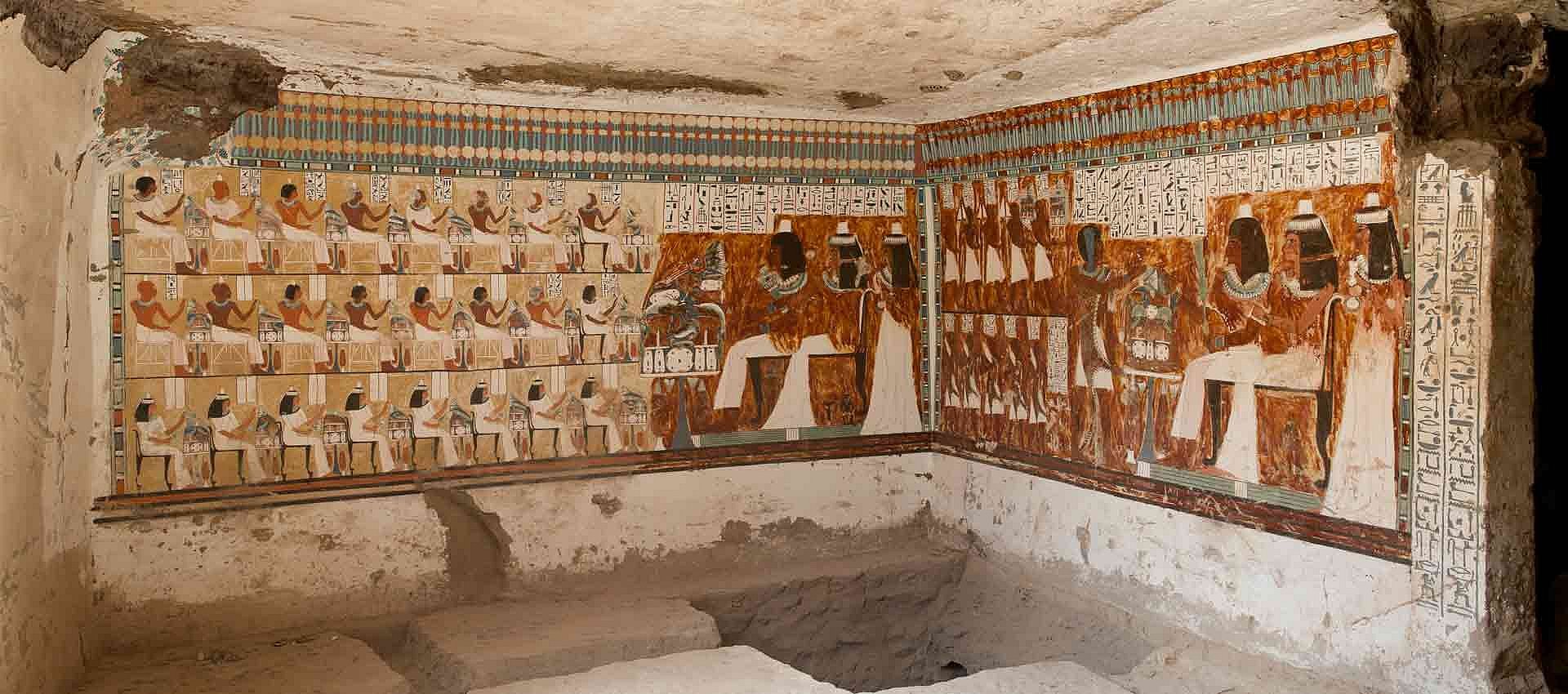

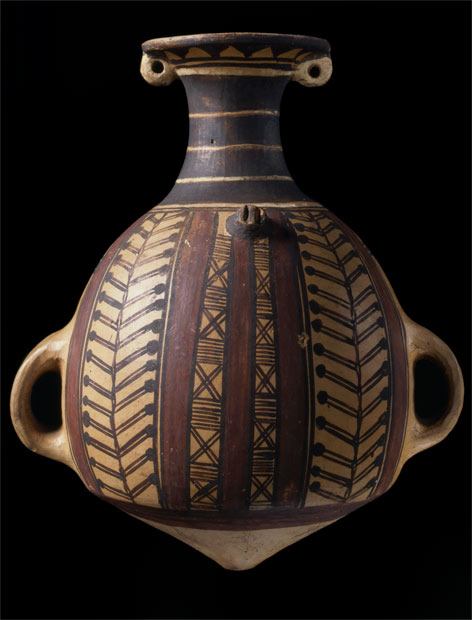

Yes, certainly. And we found significant pottery fragments in the forecourt and inner rooms of tomb QHN 4. This tomb belonged to the “mayor” and chief priest of Elephantine, Amen-hotep, and dates from the second half of the reign of Thutmose III, around 1440 BC. These finds provide evidence of the type and extent of the burial and funerary pottery used at that time. There are also Aegean import vessels and fragments of inscribed wine amphora, which we have yet to decipher.

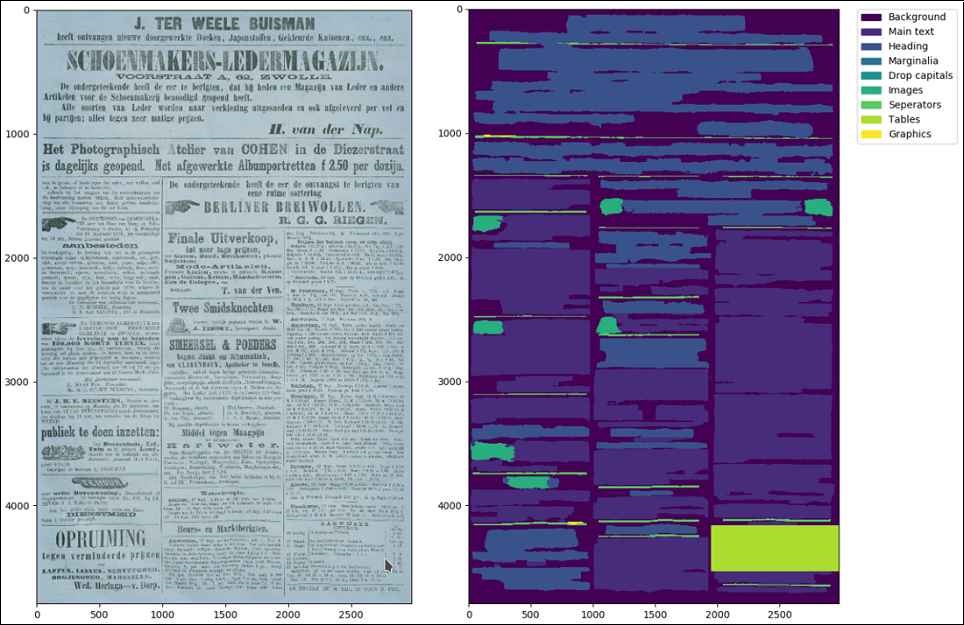

And you lay out all these shards next to one another?

We section off an area of sand, flatten it out, lay down large mats, and sort out the shards according to their shape, type, and place of origin. We call this a “shard garden.” Then the puzzle work begins. We glue the vessels together; draw, photograph, and describe them; and conduct ceramological analyses, usually under simple tents for protection. All the insights that we gain from this process of documentation – from the pottery to the tomb architecture and inscriptions – combine to give us a larger picture.

I understand you’re planning an exhibition for September in the Ägyptisches Museum?

That’s right. It’s going to be a small exhibition dedicated to the dig, called Robbed – Ransacked – Rescued [?]: The Tombs of the Qubbet el-Hawa North. We want to present our work to visitors at the Neues Museum and give them some insight into the research we’re conducting. Of course, we can’t show any of the finds. But the photographic replica of User’s tomb paintings will be fascinating to see. And it will be a good complement to our internationally renowned exhibition on Ancient Egyptian culture, which has everything an Egyptophile visitor could wish to see.