The famous Prussia Collection of Königsberg was long considered lost. Now it is being reconstructed and recatalogued at the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte.

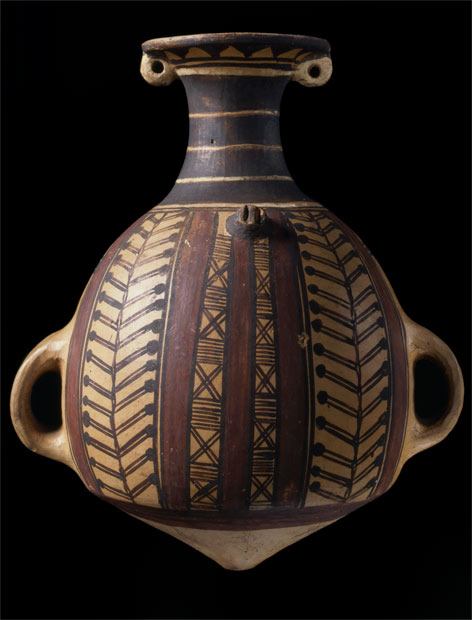

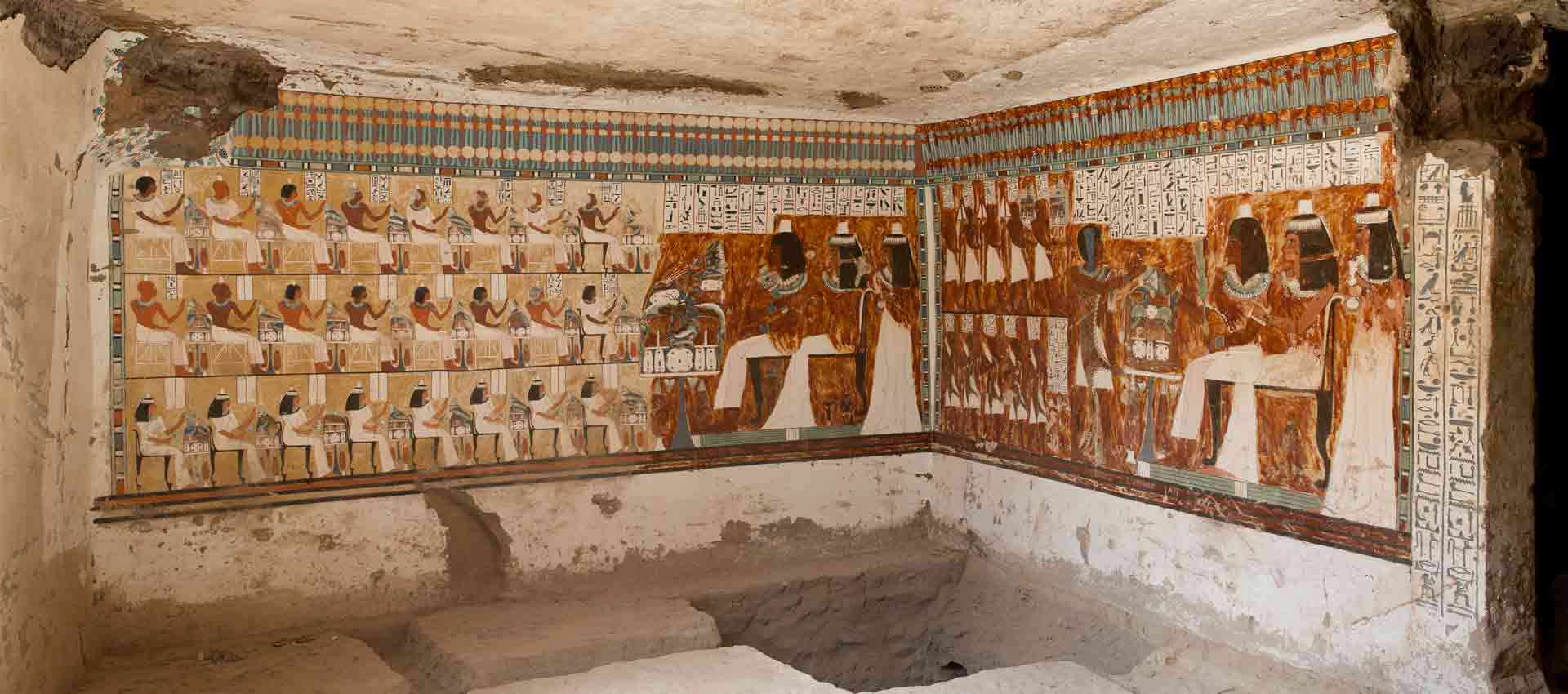

Heidemarie Eilbracht, an archaeologist with a passion for her work at the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte (Museum of Prehistory and Early History), is raving about a sword. It comes from Wiskiauten, a large burial ground in Samland near the Baltic Sea coast, an actual Viking cemetery – and it is on display at the Neues Museum in Berlin. The sword is made of iron and is decorated with silver and copper wire. It was crafted in the tenth century AD in Scandinavia. “A magnificent item, even in its current condition,” says Eilbracht. “For me, it illustrates the great skill of the craftsmen of that time and represents the connections among people and things in the regions north and south of the Baltic Sea.”

Iron sword from the 10th century, decorated with silver and copper wires. It was found in a grave of the Viking cemetery of Wiskiauten, formerly Kr. Fischhausen, today Mochovoe, Zelenogradskij rajon, Kaliningradskaja oblast', RU. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, Photo: Claudia Plamp

That is one of the reasons why the archeology of former East Prussia is such a special, fascinating subject of research for Eilbracht: the central location of the region between several geographical parts of Europe, and the cultural influences that were absorbed from all sides in the landscapes along the southeastern coast of the Baltic Sea. Eilbracht tells of the flourishing amber trade in the region, which began in the Stone Age and made it prosperous. She tells of the Christianization imposed by the Knights of the Teutonic Order, which began late in East Prussia – a fact that explains why jewelry, riding accessories, and weapons were still being placed in graves in the Middle Ages. This is a stroke of luck for anyone who wants to know how the people lived at that time. And she speaks with enthusiasm of the highly active tradition of archaeological research that existed in East Prussia long before a new chapter opened after 1945. It is a tradition that she and her colleagues and partners in Germany, Poland, Lithuania, and Russia are now continuing in a major research project scheduled to last eighteen years.

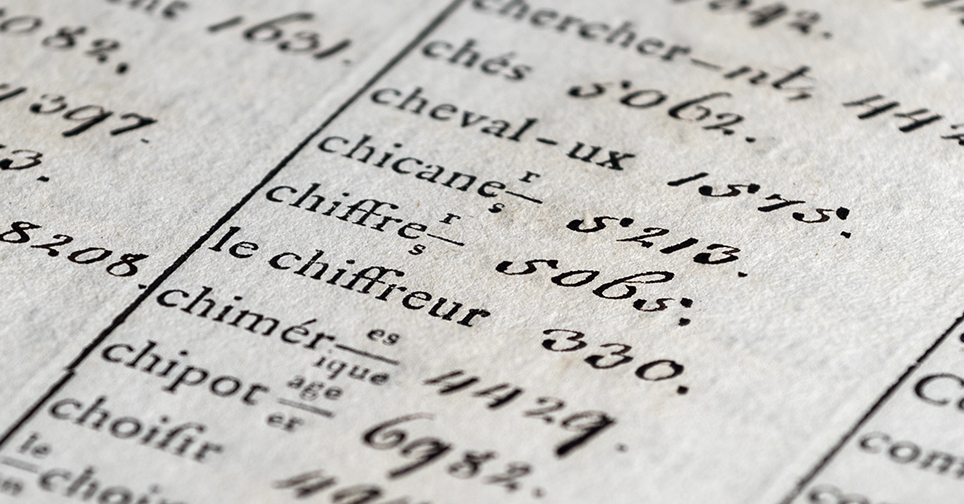

The project is primarily concerned with the impressive Prussia Collection of Königsberg, comprising several hundred thousand objects and archival documents – a collection that was, at one time, unrivaled in Europe. The East Prussians became fascinated with archeology quite early on. In 1790, the “Physical-Economic Society” was formed, a community of scholars and amateur enthusiasts in the region. In 1844, a second large association was established: the “Prussian Antiquity Society.” Both societies carried out excavations and set up archaeological institutions; it was from these institutions that the Prussia Collection later emerged. The archaeological treasures were presented in a museum in Königsberg Castle, a highly prestigious setting. But then came the Second World War, and the valuable objects and important files were scattered. For four decades, the whereabouts of the Prussia Collection was unknown.

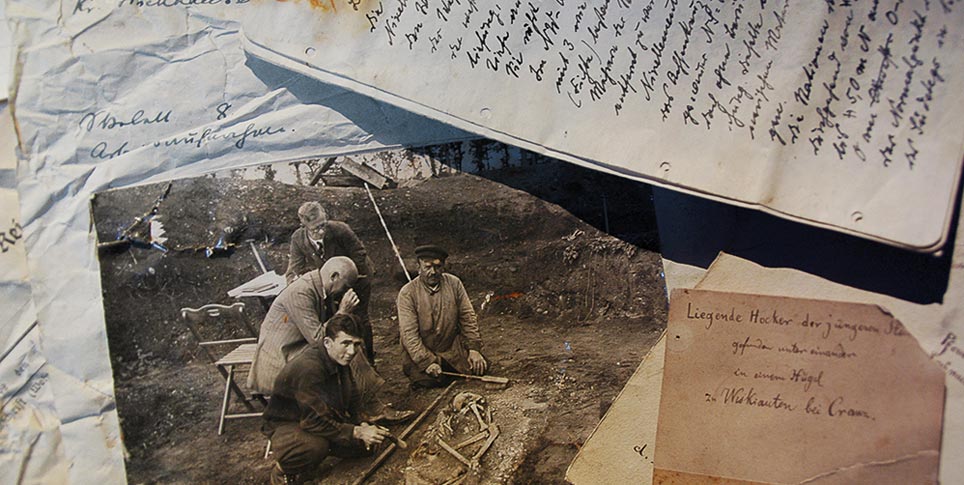

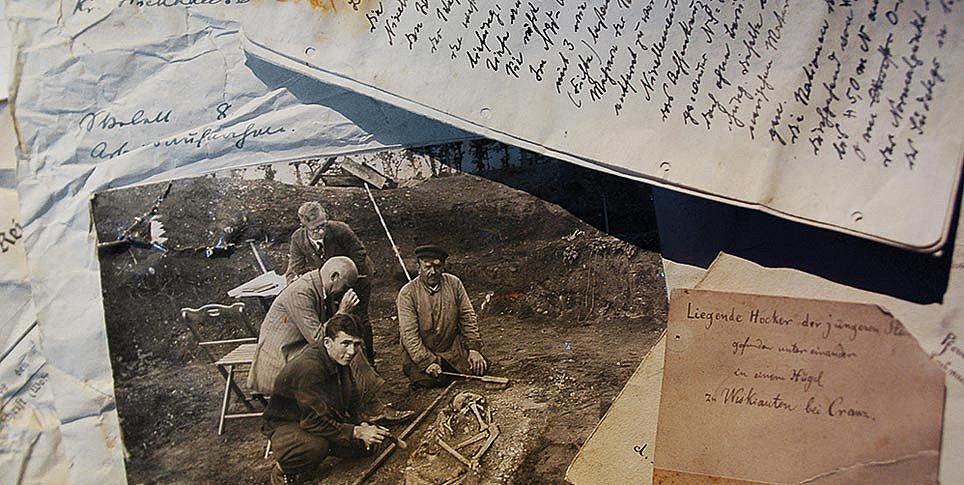

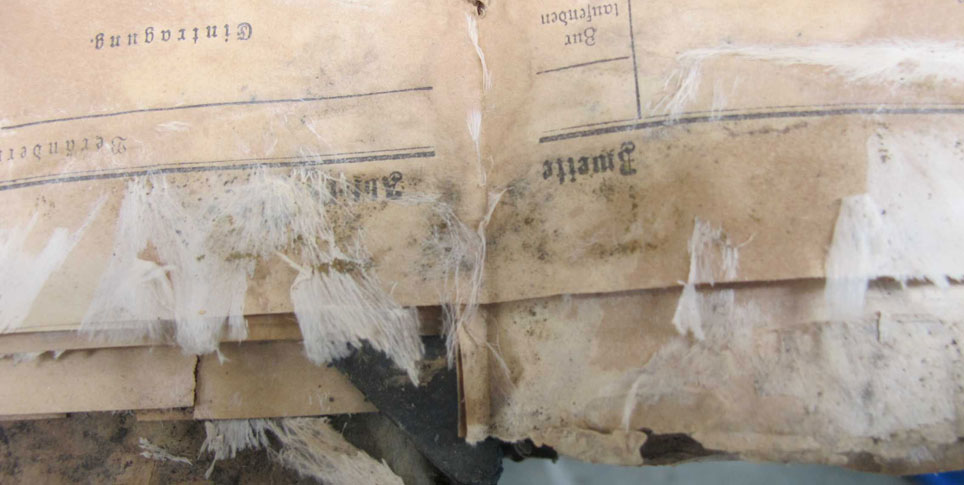

It transpired that the greater part of it had ended up in Western Pomerania, in Broock Castle near the town of Demmin. It was being held there in poor conditions. Children played with the stone axes and bronze arrowheads. It was said that files were used to start fires in the kitchen. And evidently, it was only thanks to the prudent director of the local county museum that the wooden crates with the remains of the collection were ultimately brought to the Academy of Sciences in East Berlin – where their existence was kept under wraps for political reasons. It wasn't until 1990 and the fall of the Berlin Wall that the finds and archival documents could be officially unpacked, viewed, given a light cleaning and then packed anew. It was a Herculean task: the researchers had to reassemble a puzzle of a hundred thousand pieces. Approximately 50,000 objects of iron, bronze, silver, and leather had been saved, along with about 50,000 individual pages documenting the finds, plus photographs and plans and maps that give crucial clues to the roughly 2,600 sites where the objects had been found in what was formerly East Prussia.

“Continuity of Research and Research of Continuity – Basic Research on Iron Age Settlement Archeology in the Baltic Region”

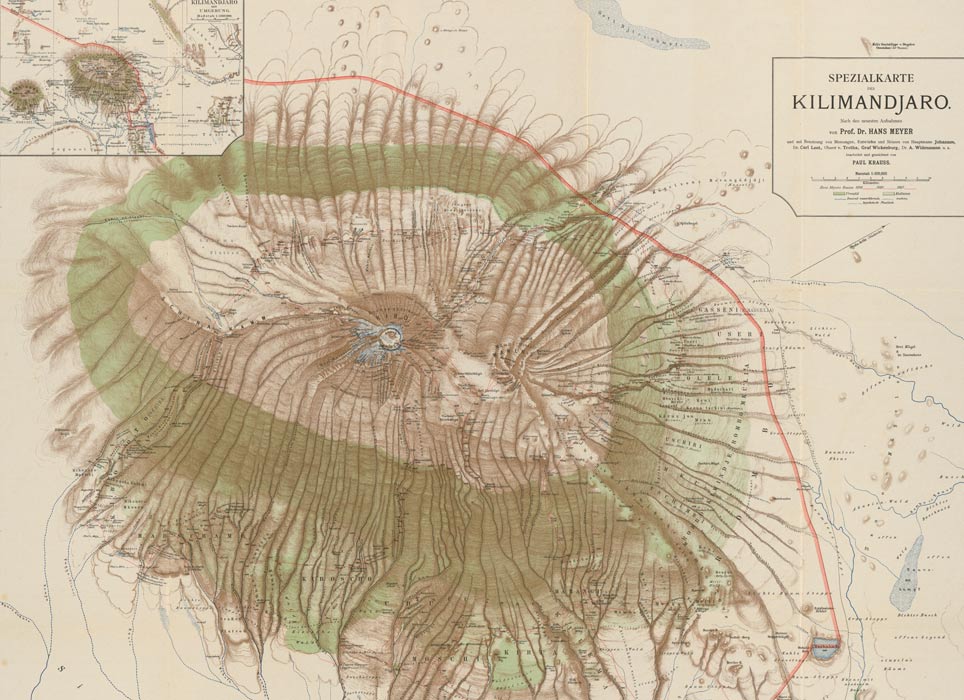

Work on the project “Continuity of Research and Research of Continuity – Basic Research on Iron Age Settlement Archeology in the Baltic Region” began in January 2012. The institutional participants are the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte in Berlin, directed by Professor Matthias Wemhoff, and the Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archeology in Schleswig, directed by Professor Claus von Carnap-Bornheim. The project receives support from the Academy of Sciences and Literature in Mainz. It deals with the reconstruction and reassessment of the long tradition of archaeological investigations in the former East Prussia. Its work includes cataloging source material and making it available for research, relocating and confirming the sites of archaeological finds, and studying and dating selected monuments. Working together with international partners, the participants aim to recover this dense archaeological landscape and at the same time to permanently safeguard the unique cultural heritage of this region, reintegrating it into European research.

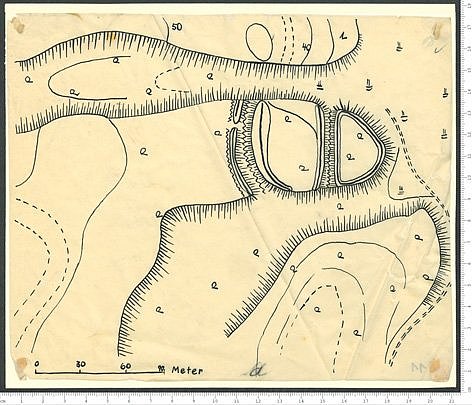

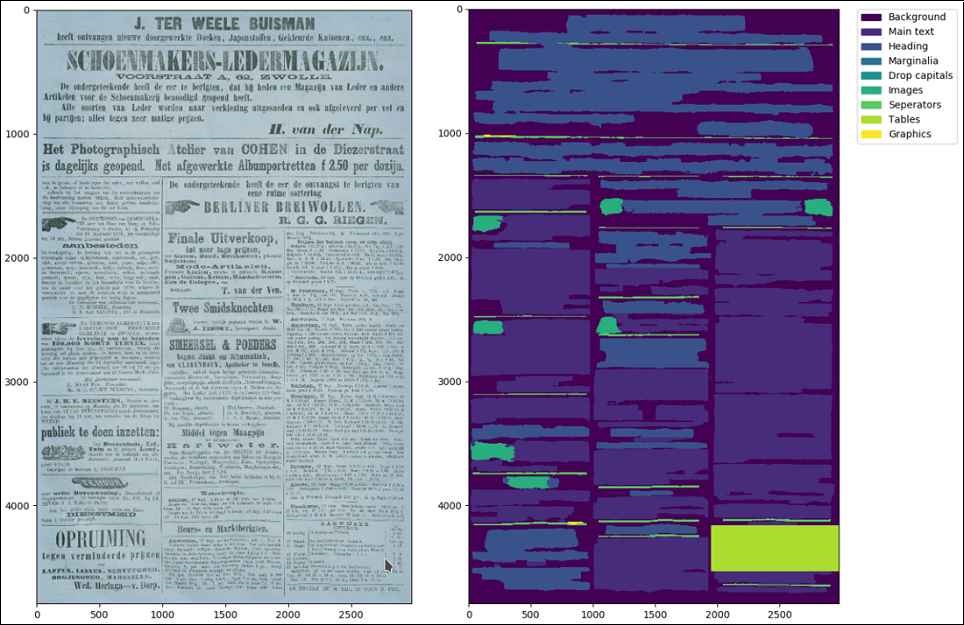

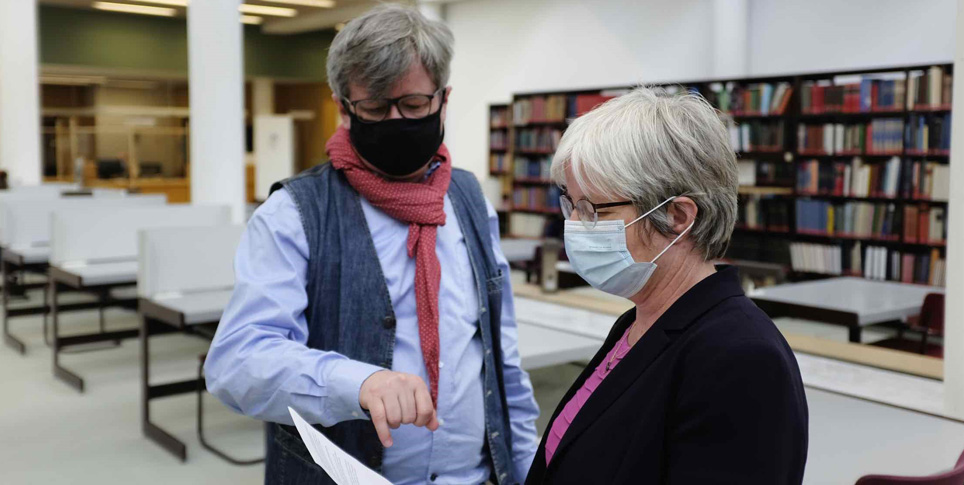

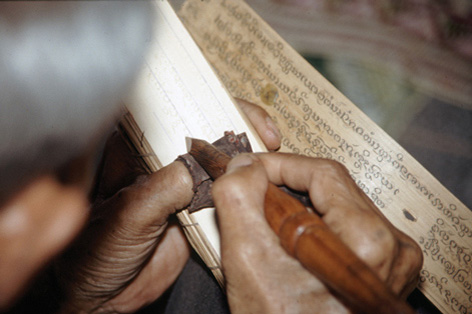

Heidemarie Eilbracht is one of the researchers who are now reconstructing and reassessing the collection. “Every fragment that is matched makes me happy,” she says. “There might be two parts of an artifact that fit together all of a sudden, or a newly discovered document that provides important information on some site in East Prussia with archaeological remains.” She is deeply gratified that the Prussia Collection has survived to such a great extent at all. Of course, Eilbracht wants to recover and preserve the knowledge about finds and excavations, about monuments and the locations where objects were found, about researchers and research activities, but she also very much wants to make this fantastic cultural heritage available in its entirety for current and future studies and to reintegrate it, so to say, into European research. To that end, all of the information from the pre-war era is being organized in a database. Its name is “prussia museum digital.” In May 2021, the database portal was opened to the scientific community and other registered users. For a long-term project that involves so much international cooperation, that is a big success to begin with.

At present, the database comprises the Königsberg objects that are kept in the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte. They will be followed by objects held at other locations, including the museums in Allenstein (Olsztyn) in Poland and Kaliningrad in Russia, and national institutions such as the University of Göttingen and the Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archeology (ZBSA) in Schleswig. “Today, visitors can no longer physically enter the Prussia Museum in order to study the collections. But they can use the database to see what finds were kept there. Or they can check what excavations were conducted at which sites, and when,” says Eilbracht. “This is a completely new and systematic form of access to the scattered sources.”

She has undertaken several field trips herself: in Poland, in the Kaliningrad area and in Lithuania. “It's important to see a landscape with your own eyes in order to understand why people settled at this particular stream, of all places, or why they set up their cemeteries on that particular slope.”

What were the different influences contributed by the Scandinavians, the West Slavs, the empire of the Kievan Rus, and the Finno-Ugric tribes? How did Prussian customs regarding burial and grave goods change under the influence of the Teutonic Order? And in general, what made the people back then tick? These are the questions that occupy Eilbracht’s mind. “There are some who think that the people of earlier ages are long dead and can't be of any relevance to us anymore. I see it differently. The remnants that we uncover, the objects in graves and at settlement sites show how close to us they are,” she says.

For the Museum für Vor- und Frühgeschichte, the project is a stroke of good fortune, given the additional personnel and financial resources it entails. When it comes to documenting the East Prussian archival material and finds, no other institution has as much expertise and experience. Archivists, restorers, and specialists of all disciplines have been working to preserve the objects ever since they were rediscovered. And since the museum has always had very close contacts in eastern Europe, it is a natural door-opener for the project. “Our current national borders have had no relevance for most eras of prehistory and early history, so there are many research questions that can't be studied comprehensively in national contexts,” says Eilbracht. “Yes, archeology is political too. It promotes mutual knowledge and understanding. And I hope it will do so even more strongly in the future.” That is really not backward-looking at all.