School reports, wills, Letters of Enfeoffment: The Brandenburg-Preussisches Hausarchiv has a fascinating history. The official records and legal documents contained in the archive are now being made accessible for the first time.

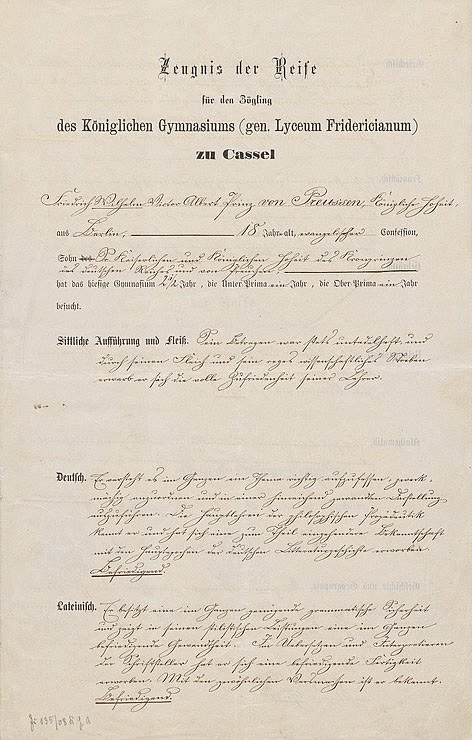

This pupil looked destined for great things: "His conduct was at all times beyond reproach, and his diligence and keen application to his subjects earned him the full satisfaction of his instructors." The German emperor’s grandson, who would one day be crowned Wilhelm II, was 18 years old when he took his Abitur (secondary school exam) in January 1877. Although his "upstanding conduct and diligence" were impressive, he received a grade of no better than “satisfactory” in Latin, Greek, German, and mathematics, and he was excused from physical education. The Gymnasium (secondary school) that the young man attended in Kassel graduated him "with best blessings."

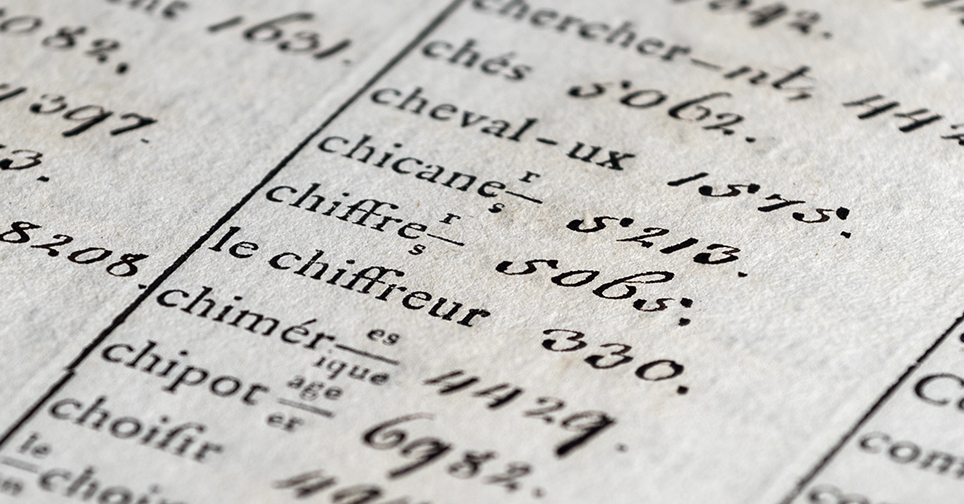

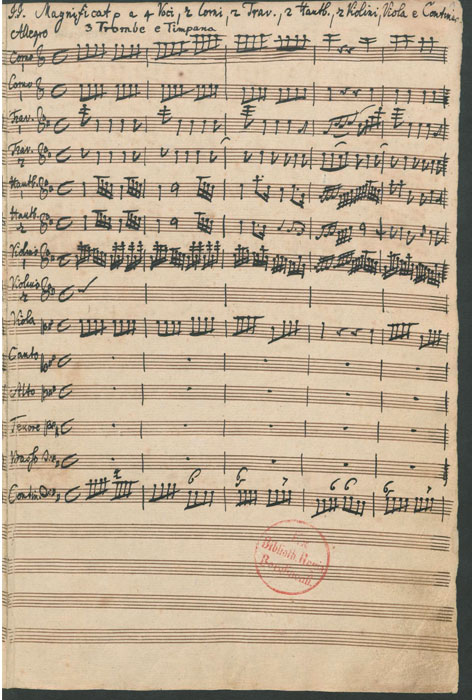

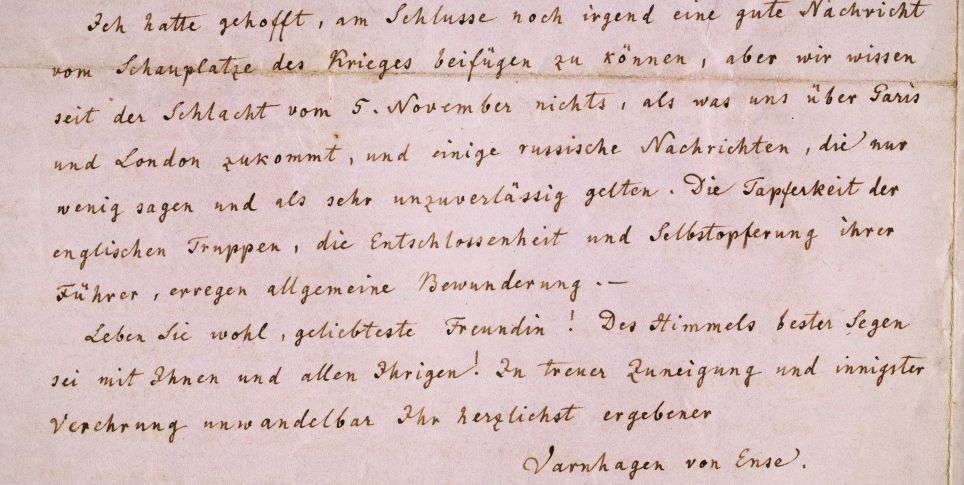

Wilhelm's Abitur certificate is one of the documents concerning the Hohenzollern dynasty currently held in the Brandenburg-Preussisches Hausarchiv, an archive of the royal house of Prussia. It contains approximately a thousand historical documents, among them great treasures: the wills of Frederick the Great and other Prussian monarchs, medieval treaties of alliance, documents related to rights of succession in Brandenburg, and gems like the reflections of Wilhelm I on New Year's Eve, composed in Versailles. There are letters of enfeoffment (deeds that granted a fief, or estate of land, in exchange for a pledge of service), documents concerning bans (feudal laws regulating the lives of peasants), certificates of appointment, treaties, diplomas, and lists of servants at the imperial court, with their names and wages. The oldest documents are from the 13th century; they described the provision of support for widows. The most recent – a proxy that Wilhelm II issued for a plenipotentiary from his exile in the Netherlands – dates from 1938.

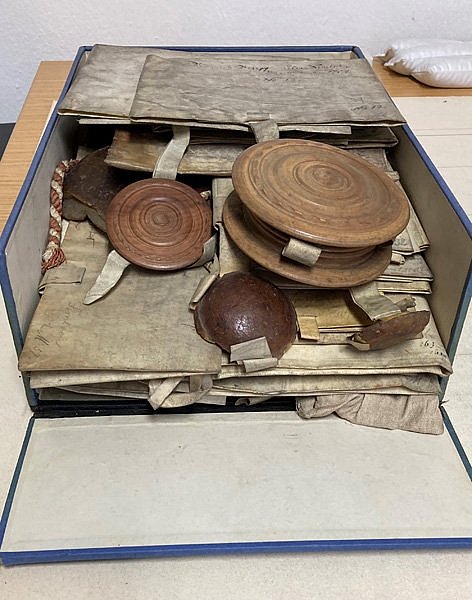

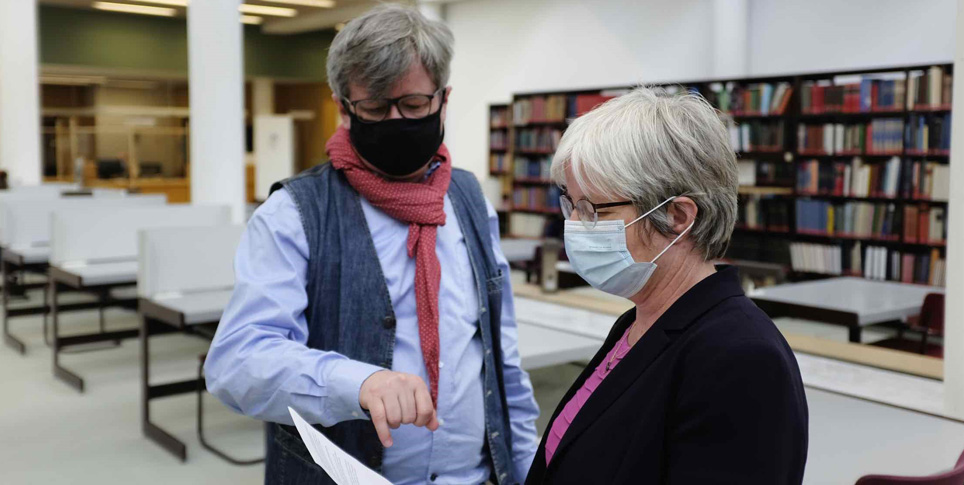

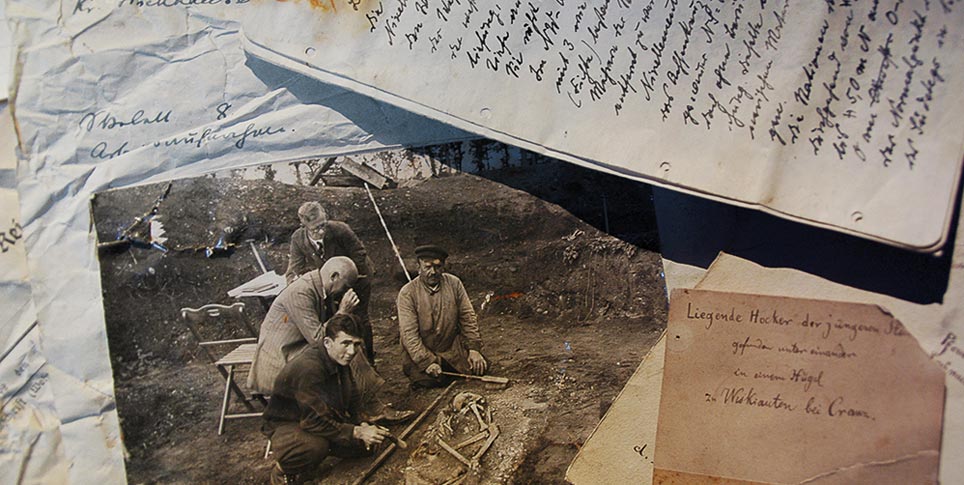

Now the archive is being indexed with support from the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media. "It's fascinating to have such an old document in front of you," says Stefanie Fraedrich-Nowag, supervisor of the project at the Geheimes Staatsarchiv in Dahlem (Prussian Secret State Archives). "You imagine how it came about, what living conditions were like at that time, and who else had the document in their hands at some point later on." Her job is a bit like detective work; she analyzes the documents in the Brandenburg-Preussisches Hausarchiv and, in the process, helps make them accessible to the public for the first time. It isn’t at all easy going: "The documents of the Brandenburg-Preussisches Hausarchiv are in a big muddle," she says.

That has to do with its history, of course. Everything began with Friedrich Wilhelm IV. When he was still crown prince, he made a pastime of collecting works of history, especially in relation to the history of the Prussian royal family. On collecting and editing, he took advice from the famous historian Rudolf von Stillfried-Rattowitz.

Before long, Stillfried suggested that his patron create his own archive for the source materials from the Hohenzollern family. And this archive, an archive maintained by the royal house of Prussia itself, was indeed established after the failed revolution of 1848, which shows that it was created in part for political reasons. "King Friedrich Wilhelm IV wanted the archive of the Hohenzollern dynasty so he could safeguard his documents and, by extension, his claims to authority and the things he owned. After 1848, especially, he wanted to maintain control over his financial affairs," says Fraedrich-Nowag.

But where exactly does the state end and the private sphere begin? What belongs in a public records archive and what belongs in a family archive? In other words, what are Prussian affairs of state, and what are private matters of the Hohenzollerns? Even back then, that was not an easy question to answer. What we do know, however, is that other archives had to be plundered and torn apart on a large scale to set up Friedrich Wilhelm's archive, especially the Geheimes Staats- und Kabinettsarchiv (Secret State and Cabinet Archive), but also archives outside Prussia, because the Hohenzollerns had a Franconian and a Swabian branch and their documents were kept in a number of different states. So it is no surprise that many historians protested at the time and that the director of the state archive resigned.

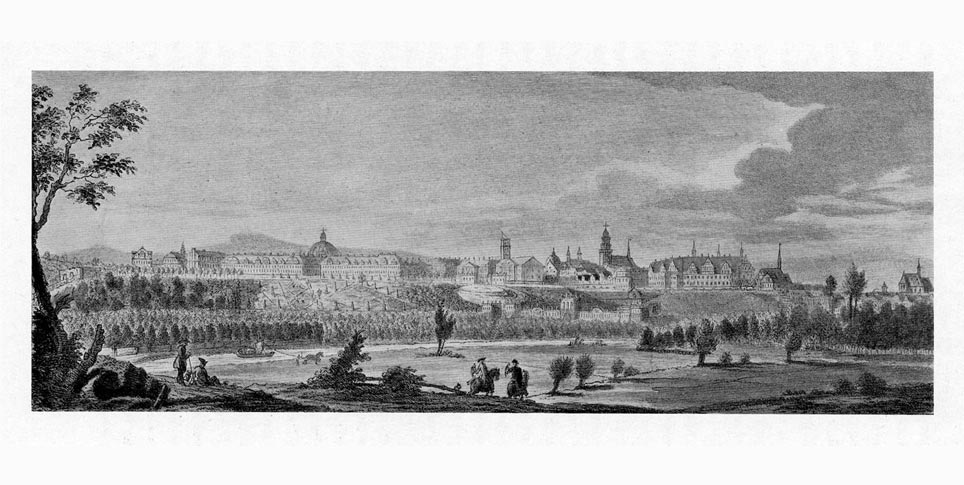

Nor is it surprising that, after 1918, there was thought of liquidating the archive. But at that point, it was too late. The archive of the Prussian royal house already had a history of its own – and had its own historical value. It had become a "living organism," it was said at the time. In the so-called compromise of 1925, it was agreed that the Prussian state and the Hohenzollerns would manage the archive jointly. The documents remained in their new location, a magnificent building at Luisenplatz in front of the palace in Charlottenburg, until more than half of them were destroyed during an air raid on the night of November 22, 1943.

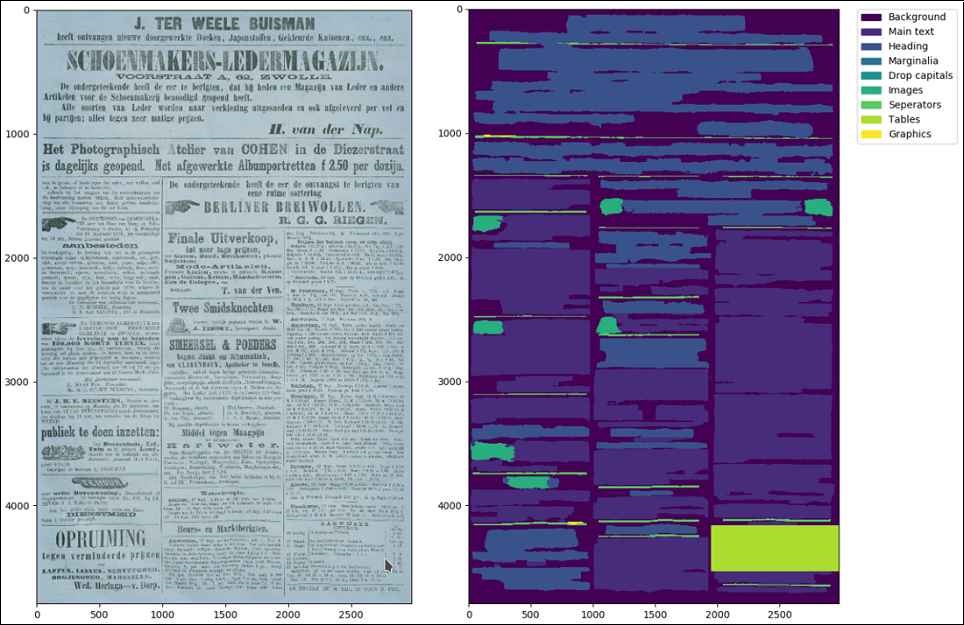

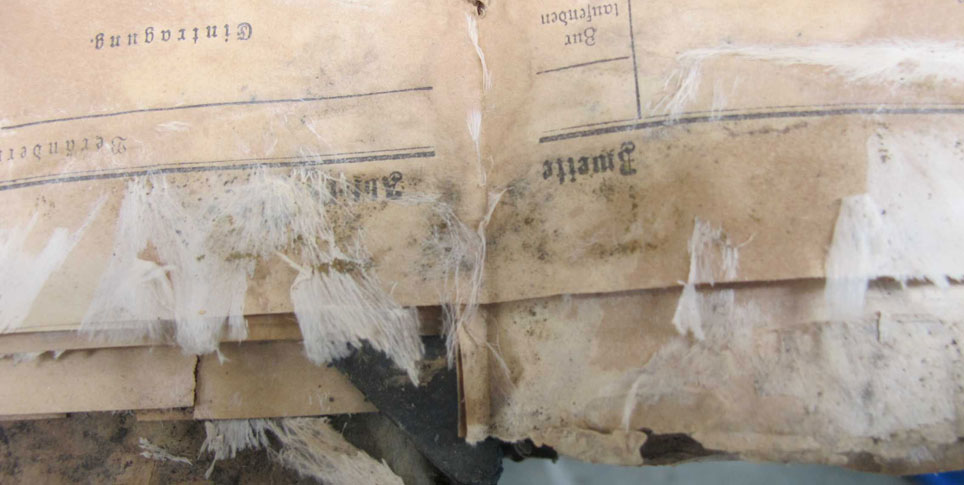

Fraedrich-Nowag has been entrusted with the job of restoring the archive, in so far as is possible, to the state it was in prior to 1943. Based on the old inventories and lists, she will attempt to identify the location of the 3,500 documents it contained at that time and make the results available online. Since last autumn, she has been cataloging up to twenty documents per day with the archiving program Augias. She hopes to answer a variety of questions: What exactly was destroyed back then and what survived? Where have the documents been kept, and when? A great deal of research is needed. Many of the documents have traveled far and wide. The stations on this journey include the manor of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem at Sonnenburg (Słońsk) near present-day Kostrzyn (for a time during World War II), then the Staßfurt salt mine near the end of the war, and finally, when it was no longer possible to cross the Elbe, a flak tower at Berlin Zoo. Later, some of the documents were transferred from the Soviet-occupied zone to the Soviet Union, then given back to East Germany bit by bit and moved to Merseburg, where they were kept with parts of the former Preussisches Geheimes Staatsarchiv (Prussian Secret State Archive).

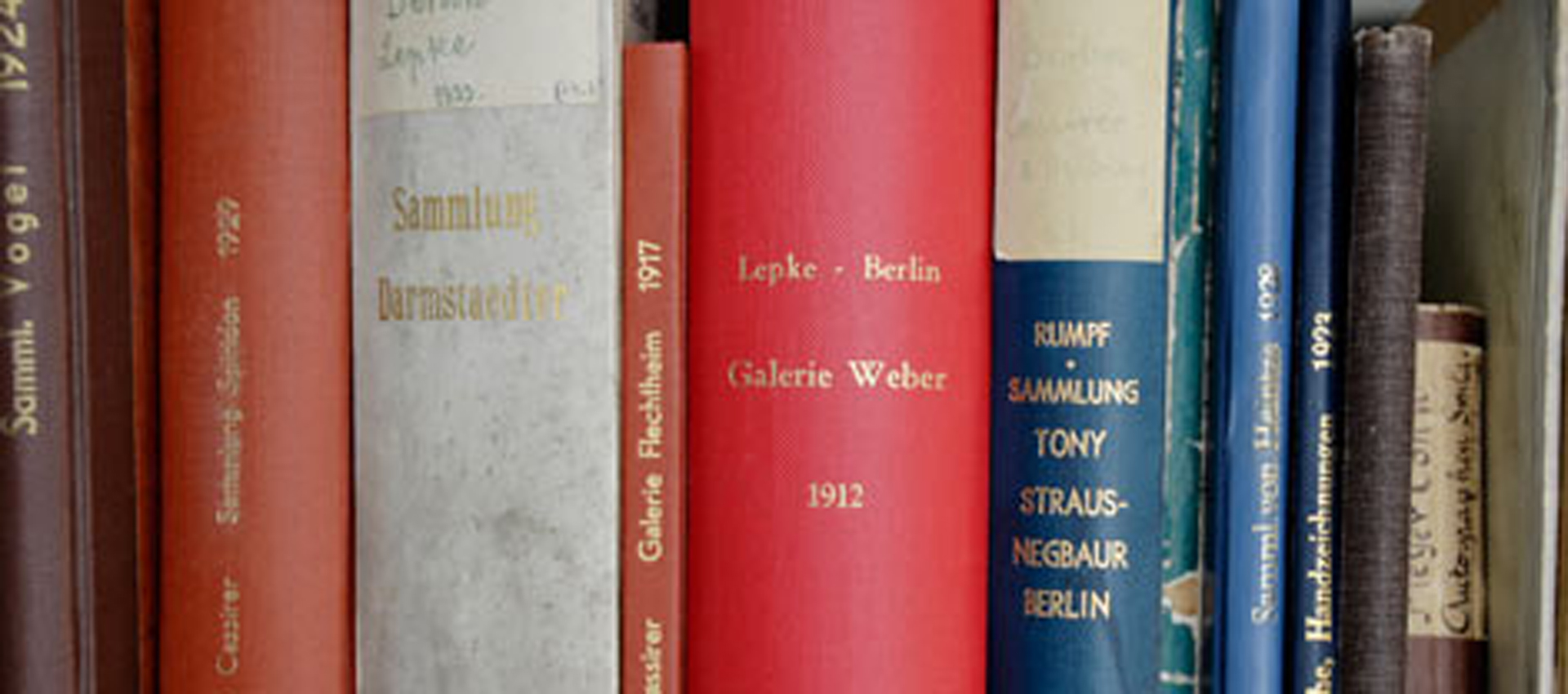

And since archives, too, are political in nature, and since the way in which old documents are preserved says a lot about who is in possession of them at any given time, there were again plans – this time in East Germany – to liquidate the monarchical archive and integrate its parts into the state archive. Evidently, that idea did not progress far beyond the planning stages. After reunification, the documents in Merseburg were moved to Dahlem, in the west of Berlin. They remain there today, along with those of the original archive that were moved from the flak tower at the zoo to the Preussisches Geheimes Staatsarchiv after the Second World War. In the 1980s, there were new acquisitions; documents were bought at auction or otherwise purchased. And it gets even more complicated: in the 1970s, approximately five hundred documents from Merseburg were delivered to what is now the Brandenburgisches Landeshauptarchiv (Brandenburg State Main Archive) in Potsdam. They now have to be identified, too.

At the Geheimes Staatsarchiv, the boxes and crates with the documents are now safe and sound in the storeroom; they occupy 25 linear meters of shelf space.

Fraedrich-Nowag is eager to understand the exciting history of this special archive. "Precise analysis of the royal Prussian archive is a big gain for research," she says. One thing is clear already: the biggest gaps are in the birth, baptism, and marriage certificates, as well as the enfeoffment documents. Many pieces of the archive will have to be written off as lost. Nevertheless, Fraedrich-Nowag intends to complete the finding aid (a guide to records) for the archive by the end of the summer. Then the results of the project will be published in the specialist press. They are sure to arouse great interest.