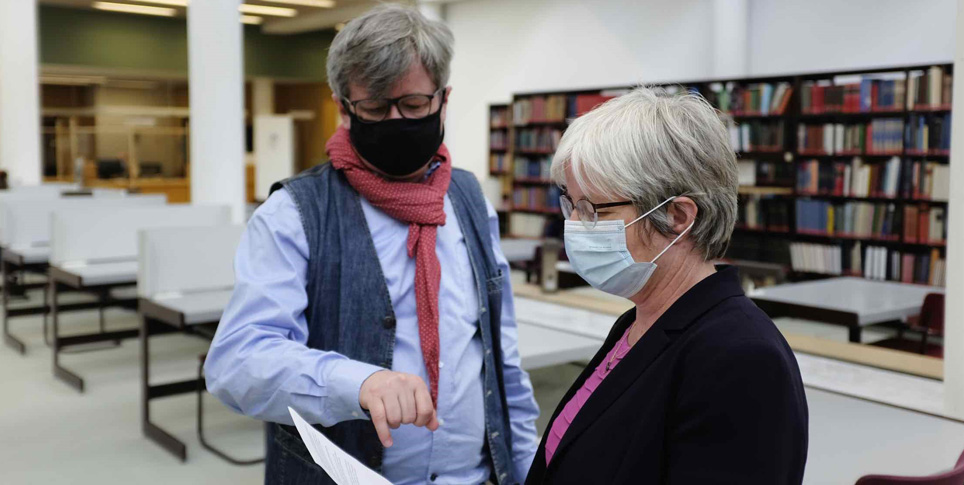

Experts at the Geheimes Staatsarchiv are beginning to solve the last riddles of Prussia’s diplomatic mail – with the help of cryptography.

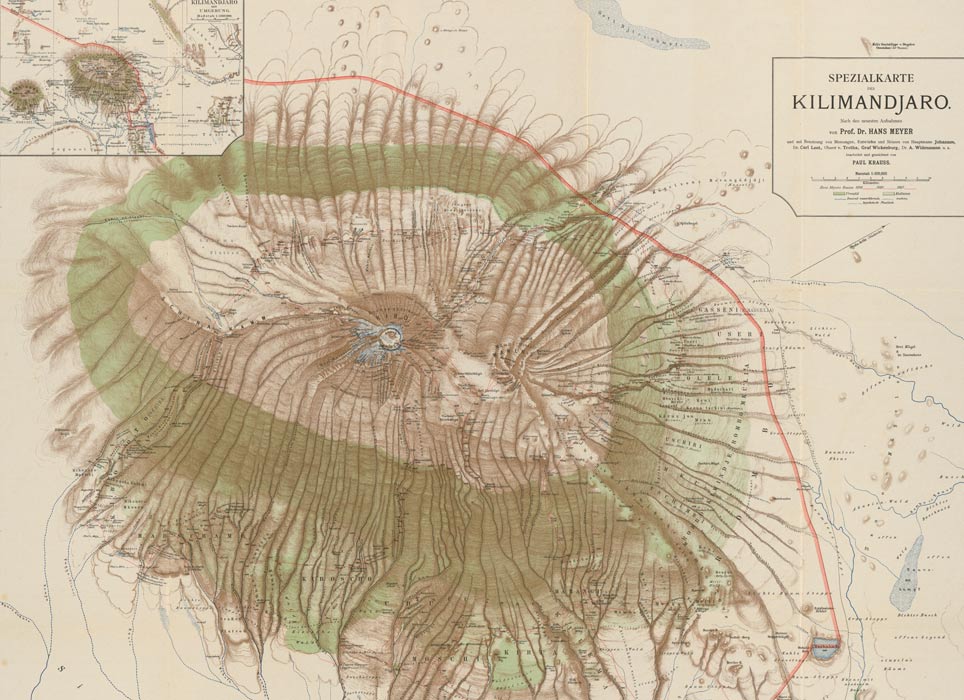

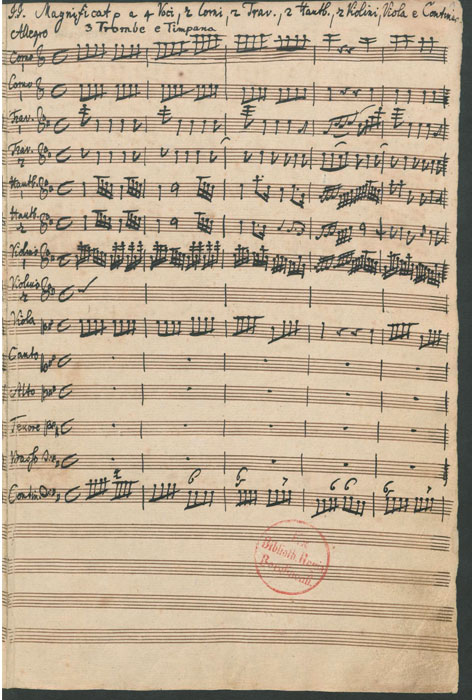

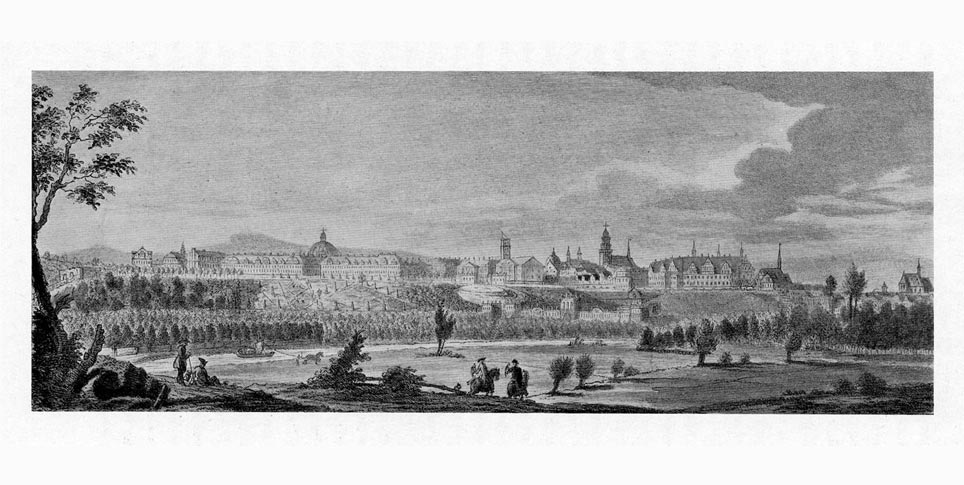

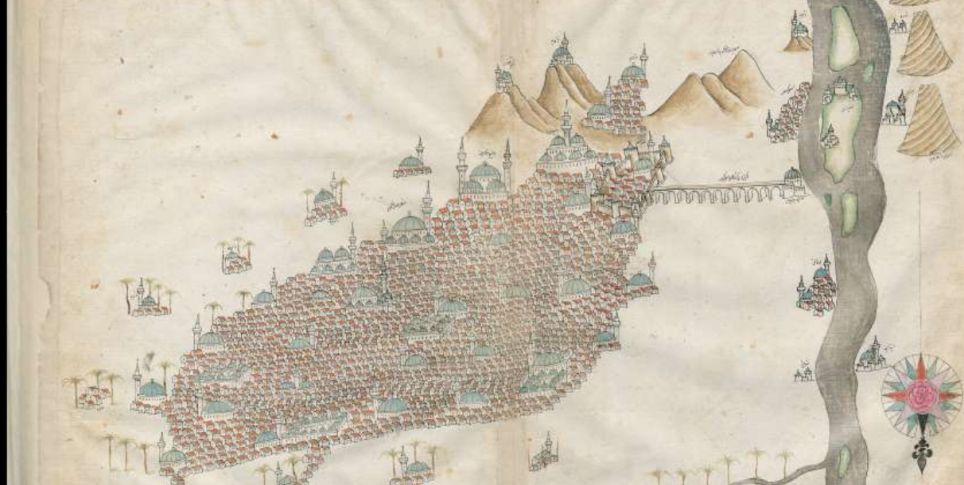

Piles of old dispatches lie in Franziska Mücke’s office. They are reports sent to Berlin from Rome, Paris, and Saint Petersburg by Girolamo Lucchesini. Before he embarked on a brilliant diplomatic career, Lucchesini was the last reader for Frederick the Great – and a confidante of the king.“ Marquis Lucchesini was particularly diligent in his reporting,” says Franziska Mücke, leafing through the valuable documents. When she points to an interesting comment here and an unusual font there, it is less with a sense of reverential awe, as one might expect, than of respectful familiarity. This is the stuff of Franziska Mücke’s daily work. She is an archivist, occupying a roomy office on the ground floor of the Geheimes Staatsarchiv (Secret State Archives) in Berlin’s Dahlem district. The diplomatic correspondence in the archives amounts to eleven thousand volumes. It was sent to Berlin by Prussia’s ambassadors between the early sixteenth century and 1806, when the Prussian state collapsed. Most of these letters were encrypted, like Lucchesini’s. Encrypted texts from Wilhelm von Humboldt have also survived, dating from the period when the Prussian scholar was the envoy to the Holy See in Rome.

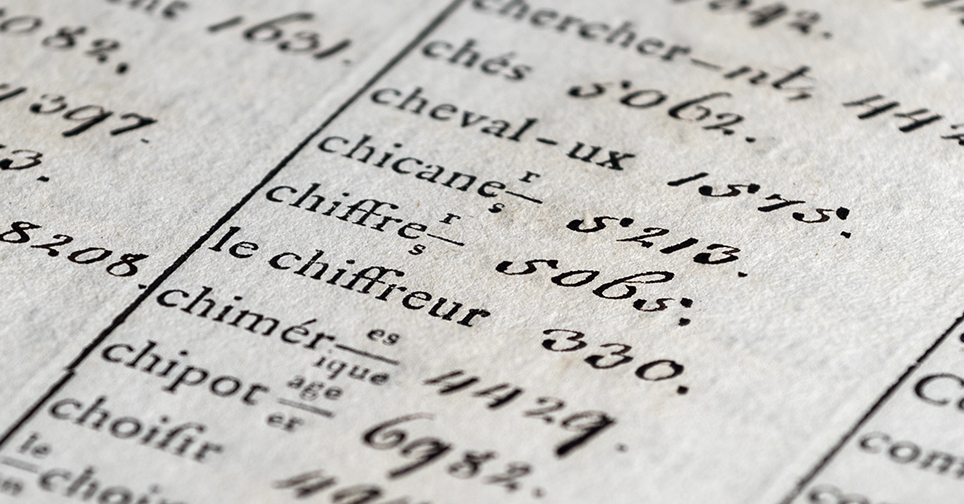

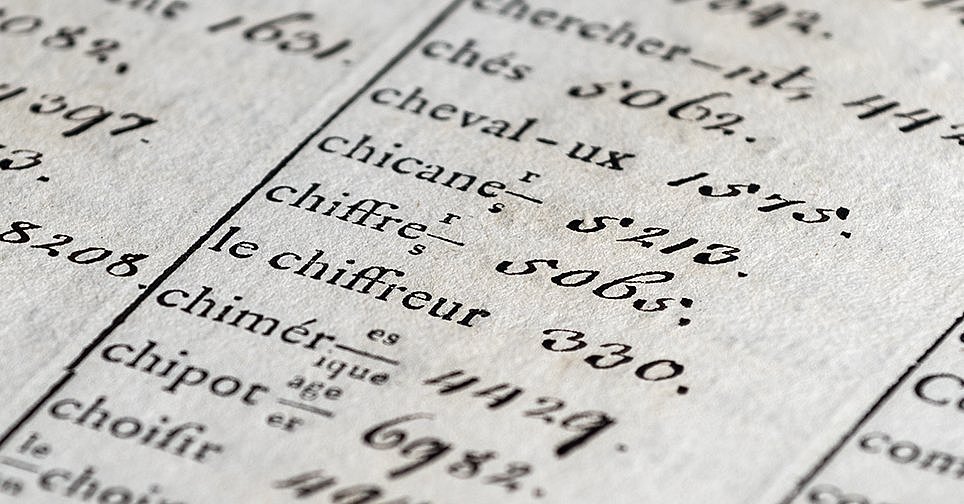

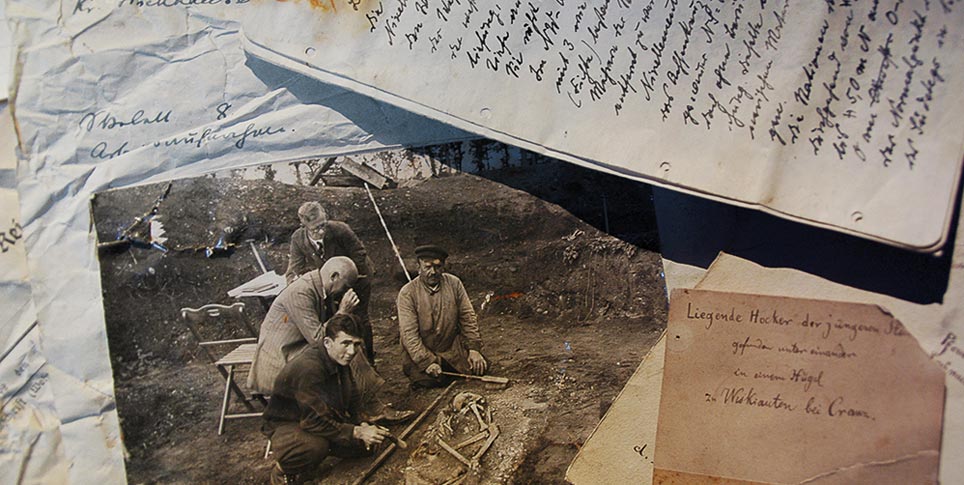

After all, dispatches sometimes fell into the wrong hands along the way. In order to prevent spies from understanding them, Lucchesini, an Italian nobleman, used number combinations: each word was denoted by a different combination of four digits. To decode such messages, the corresponding decryption tables, also called nomenclators, were needed. Only the envoy and the government secretaries in Berlin possessed copies of these. Franziska Mücke pulls a nomenclator with the title 1800. Chiffre-Déchiffrant avec le Ministre du Roi Marquis de Lucchesini à Paris across her large desk. She points out with a smile that the bottom right-hand corner of the volume is badly worn. How many people must moistened their thumbs and leafed through the pages with their brows furrowed in concentration? The secretaries had to turn them back and forth, word for word, until they had deciphered Lucchesini’s latest news from the Napoleonic court.

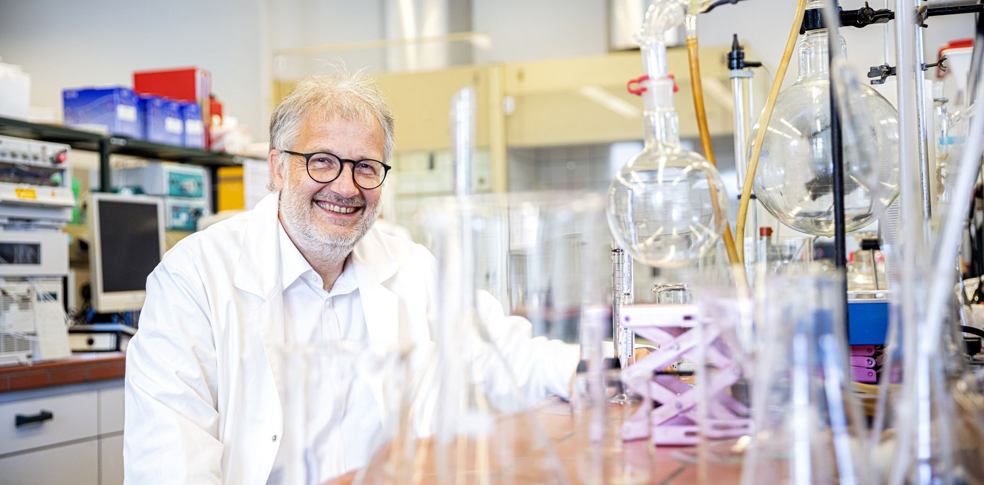

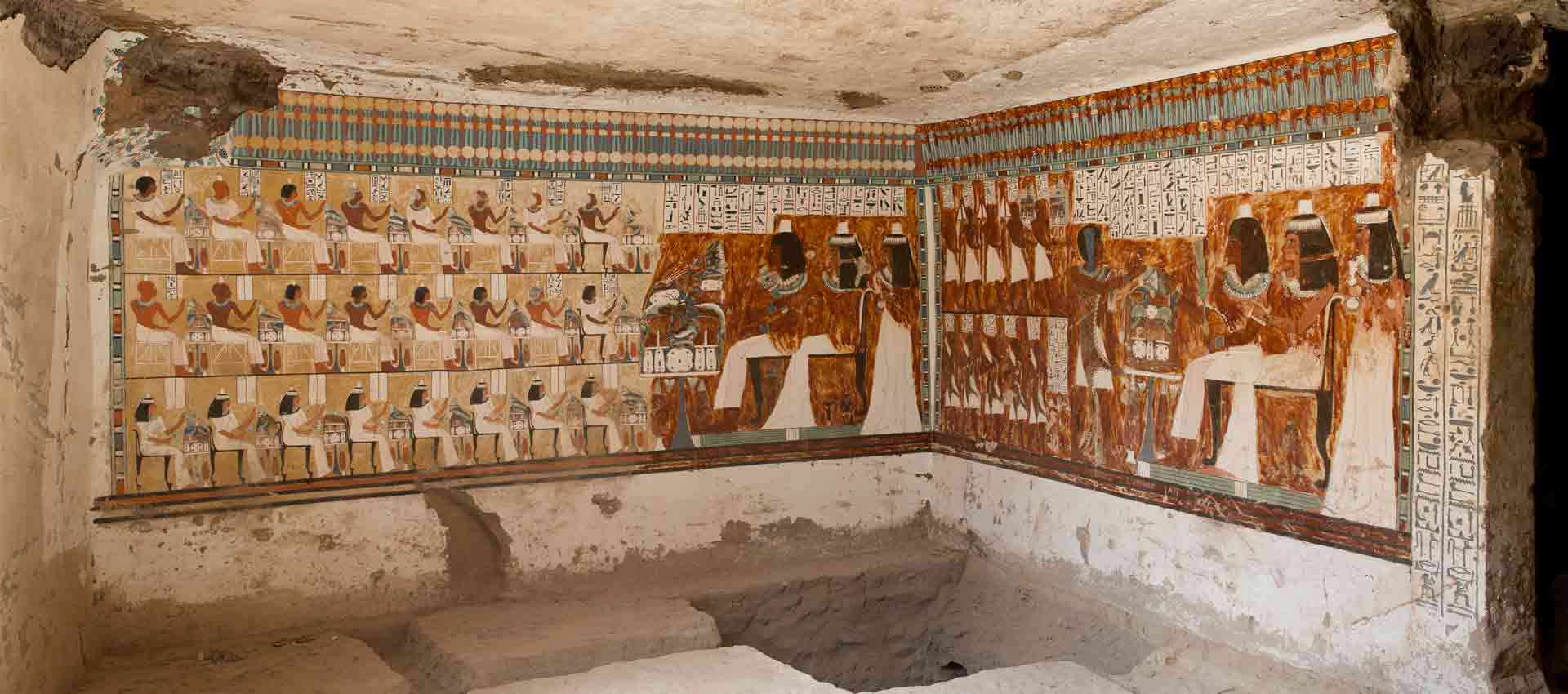

As an archivist, Franziska Mücke also has to be familiar with cryptography, the science of encrypted messages. “Cryptography is still an exotic subject,” she says. Even in ancient times, people used codes to conceal information from the eyes of others, be it a love letter, a military secret, diplomatic dispatches, or spiritual literature. The Spartans, for example, would write a message on a narrow strip of leather, wound around a rod. When the leather was unwound, the text was no longer legible. The recipient needed a rod of the same thickness in order to read the message. The art of cryptography developed in parallel with the means of communication: in World War II, complex mechanical devices were built to encipher messages sent by radio – and even more complex ones to decipher them. New methods of encryption were constantly being devised – and even more so nowadays. Be it for online shopping, messenger services, or transferring money: the crucial things are a powerful password, a regularly changed PIN, and end-to-end encryption. Digital communication would be inconceivable without cyber security.

Girolamo Lucchesini was a master of the art of secrecy. His letters were delivered by a messenger employed solely for that purpose. The king received one copy; the other went to the ministry concerned. “My impression is that a new code was used each year,” says Franziska Mücke. Did Lucchesini encrypt his letters himself or was it merely done under his supervision? To this question, the researchers do not yet have an answer. And why didn’t he destroy the code books after leaving the diplomatic service, as the regulations would have required? He certainly wasn’t the only one to be negligent in this regard.

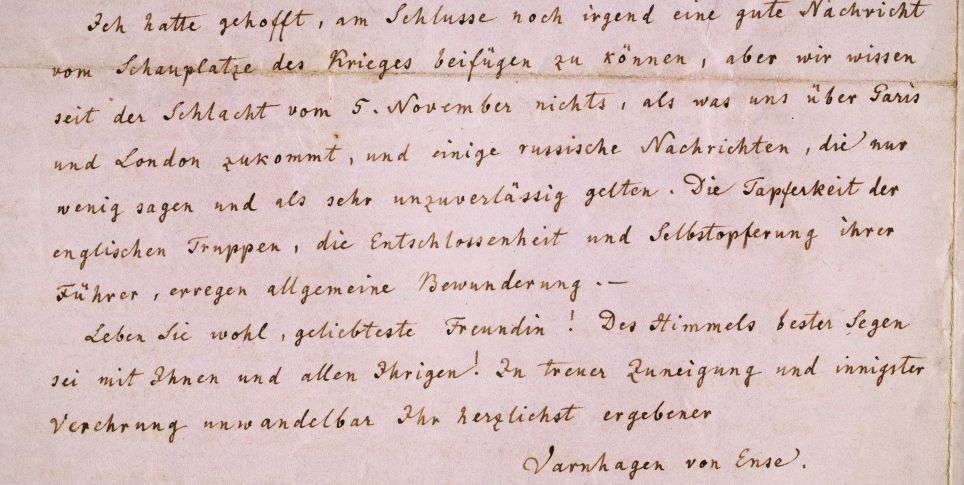

Diplomats were not alone in mastering the art of cryptography. The Geheimes Staatsarchiv – the “Memory of Prussia” – also has letters written by Princess Sophie Dorothea von Celle, the grandmother of Frederick the Great on his mother’s side, who was married against her will to the Elector of Hanover, later King George I of Great Britain. Her place in history is marked by her love affair with Count Philipp Christoph von Königsmarck, which led to an international scandal. The love-smitten princess wrote hundreds of letters to her beloved, most of them in code. Occasionally, she even used invisible ink. “Great God, what bliss and what delight, to be with you always! The more one sees you, the more one finds you superior to all the men in the world,” she wrote. But the letters were intercepted and the codes cracked. The marriage was annulled and the princess was taken to Ahlden House on the Lüneburg Heath in Germany, where she was confined for the rest of her life.

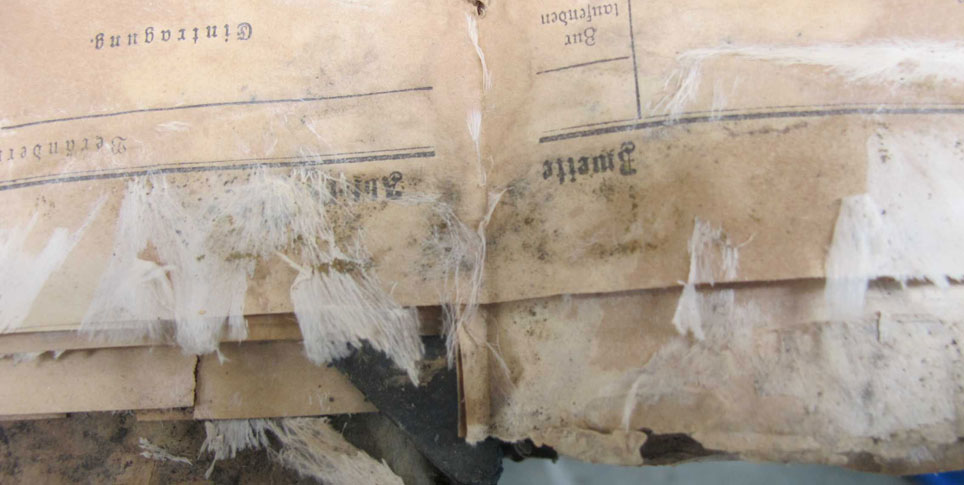

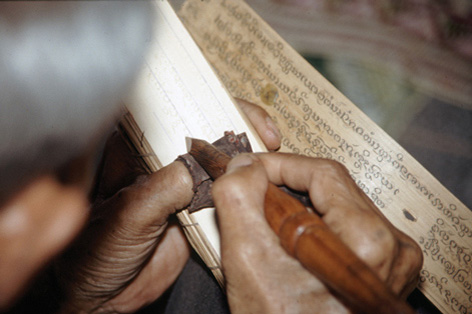

Franziska Mücke has many other fascinating stories to tell about encryption: of numbers that, while different, all represent the same letter; of numbers that stand for individual syllables or for an entire word, and of numbers that are underlined. She knows the tricks used by the envoys, the techniques to confuse code-breakers, such as writing whole paragraphs of meaningless number sequences. She knows the stories of dispatches that were incorrectly deciphered by the recipient, and of dispatches that fell into the hands of an opponent, making it necessary to change all of the codes – a laborious task. Not without reason did Frederick the Great warn his envoys, a few months after ascending to the throne, not to be lazy and to encrypt their messages diligently. Incidentally, the paper on which the letters are written is called rag paper, because it was made from a pulp of rag fibers. And the ink is called iron gall ink because it contains an extract of gallnuts.

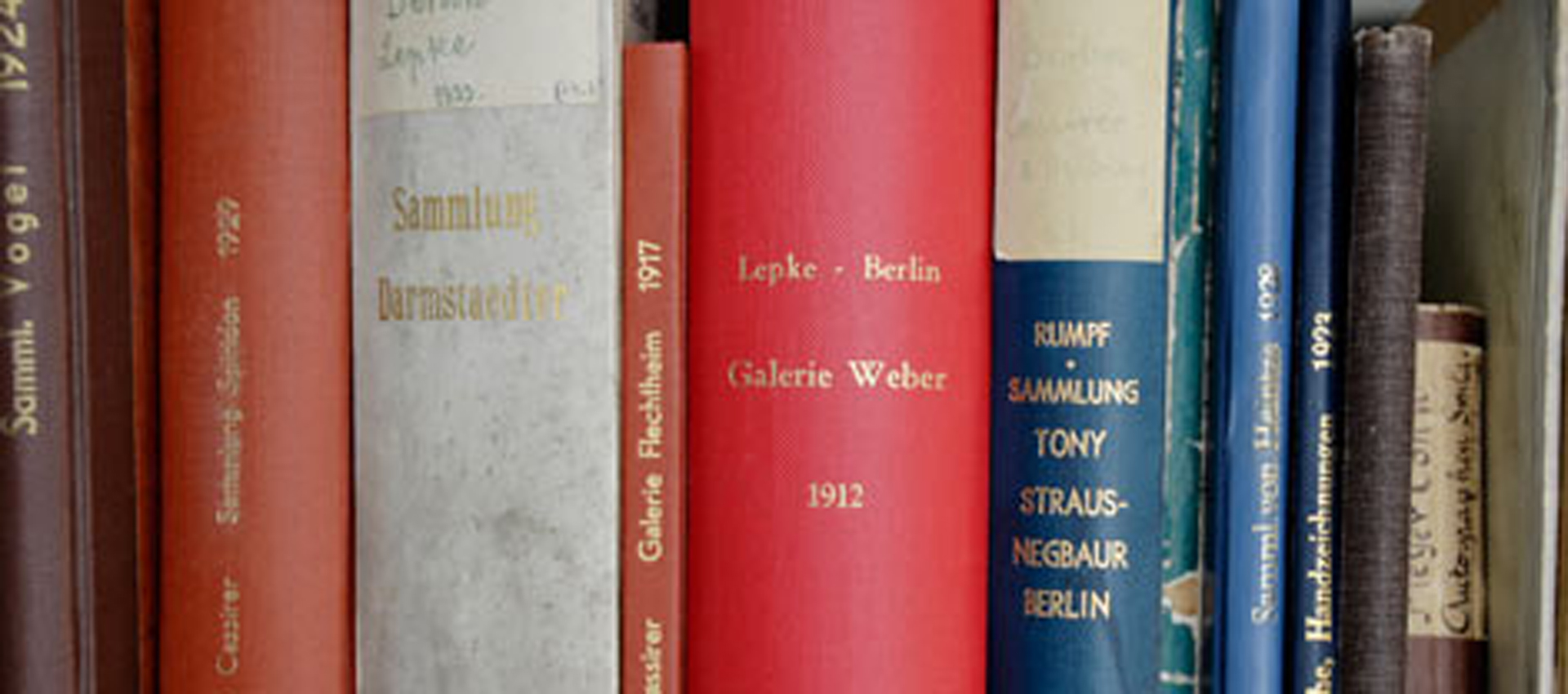

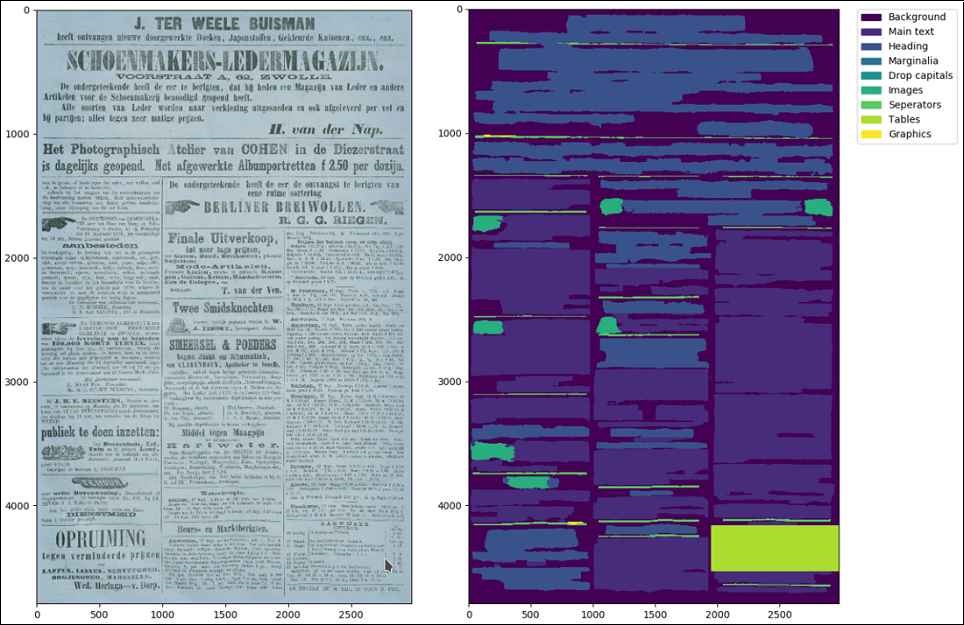

So far, cryptography has not officially been counted among the auxiliary sciences of archival science, unlike paleography (ancient handwriting), chronology (dating), the study of seals and the study of files. Now, cryptography is moving into the spotlight at the Geheimes Staatsarchiv, not least because it provides tools for gaining a better understanding of historical sources. And every bit helps, given that the archive comprises 38,000 linear meters of certificates, files, official registers, and file cards. Of these, the diplomatic correspondence of Prussia’s ambassadors, in particular, frequently turns out to include encrypted correspondence that has remained a mystery to this day. “There are still many surprises in store. We are just at the beginning,” remarks Franziska Mücke. Not until the texts have been deciphered will they reveal their value as a historical source.

And there is much to decipher – in every sense of the word. The archivist points out a comment scribbled by King Friedrich Wilhelm I under an encrypted dispatch from 1729. “Should try to decipher it,” he instructs his secretaries. The “Soldier King” couldn’t understand what the report contained. The key had been mislaid. And to date, it has not been found. But the king’s scrawled notes also present problems, because Friedrich Wilhelm I, you could say, had naturally ‘cryptic’ handwriting. “Really bad,” says Mücke, “it can hardly be deciphered!”