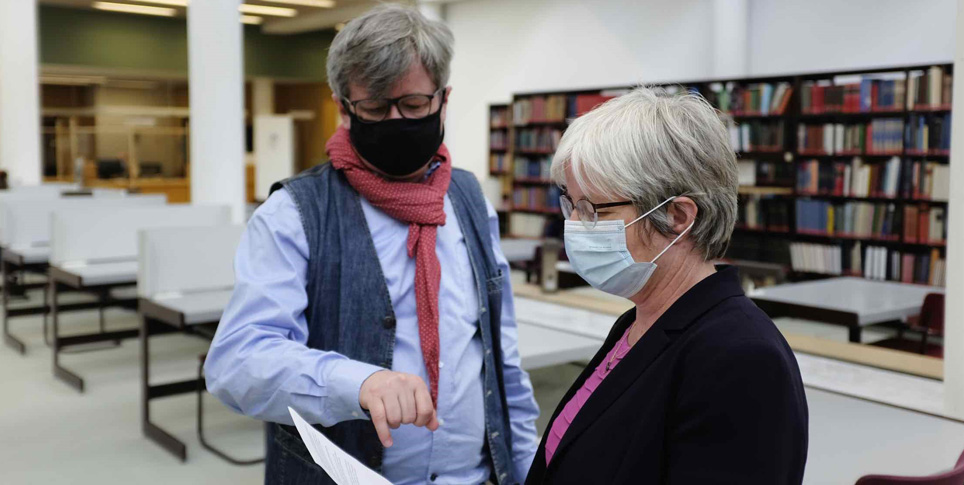

Austrian scholar Linda Erker talks about her search for clues at the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut

Dr. Erker, you are a historian at the Department of Contemporary History of the University of Vienna, where you are investigating exile and knowledge transfer as consequences of the Nazi dictatorship. Could you tell us about that?

Since 2019, I have been working on my professorial teaching qualification (habilitation) which deals with the history of Austrian scholars in exile in Latin America between 1930 and 1970. My research is currently concentrating on Chile and Argentina, and the questions of who managed to gain an academic foothold there, and in what circumstances. The period chosen for the study enables me to deal with different groups of scholars. I am interested in their biographies, their academic work, their interactions, and their networks across the caesuras of 1933/1938/1945, and I am trying to find differences and similarities between their lives and careers abroad.

What groups are you investigating?

I am mainly dealing with three different groups. As early as the 1920s and early 1930s, many academics were compelled to leave Austria’s universities and non-university research institutions (group 1). They emigrated because antisemitism, androcentrism, and anti-Socialism were dominating their daily lives and hampering their careers. The greatest brain drain occurred after the Anschluss – Austria’s annexation by Nazi Germany in March 1938 – as a result of a policy of expulsion introduced by the National Socialist regime (group 2). From the University of Vienna alone, the largest university in the country, over 300 teachers and 2,230 students – most of them Jewish – were expelled. After 1945, however, it was mainly people with a National Socialist past who went into exile in Latin America (group 3) and found success there.

After the end of World War II, all three groups found themselves – often unwillingly – part of a common, larger academic and scientific community, over 10,000 kilometers from Vienna. With regard to the scholars, I would like to know the answers to a number of questions: Did membership of a group play a role in starting a new academic career? Who performed research into which subjects, what networks existed within the German-speaking exile communities, and how did people re-establish themselves in a foreign country?

Were Latin American countries ‘classic’ places of refuge for scholars, regardless of whether they were Jewish refugees or Nazis?

Most scholars – both after the Anschluss in 1938 and after the end of the war in 1945 – moved to other centers of learning, in particular to the United States and Great Britain. Many of these transfers of science and knowledge have long been studied definitively. A number of Austrian students and scholars also fled to Latin America, which had a kind of semi-peripheral status. One of the main destinations for refugees was cosmopolitan Buenos Aires in Argentina, a country that was still flourishing economically at the time. Many scholars found a new home in other Latin American countries – or at least a temporary one, while they tried ultimately to be allowed into the United States. I am currently very occupied by two particular questions in relation to the countries of exile: What kind of academic environment did the migrants find themselves in? And how did the academic cultures of their countries of exile influence their subsequent research?

Have you found any interesting biographies yet? What did you find out in the course of your research in Chile and Argentina, as well as at the IAI in Berlin?

In the last twelve months, I have come across a number of scholars, who I would like to research in greater depth in the future.

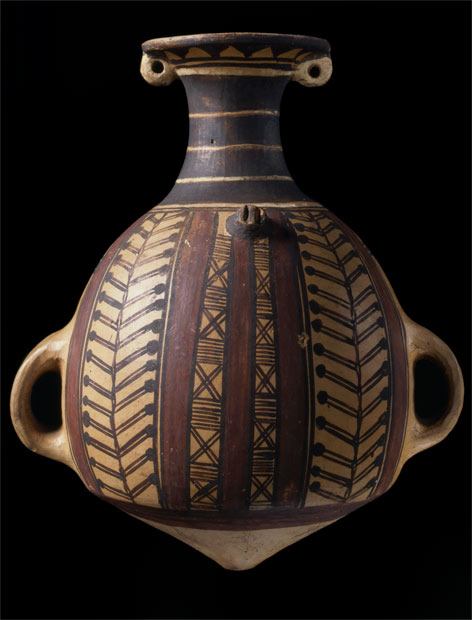

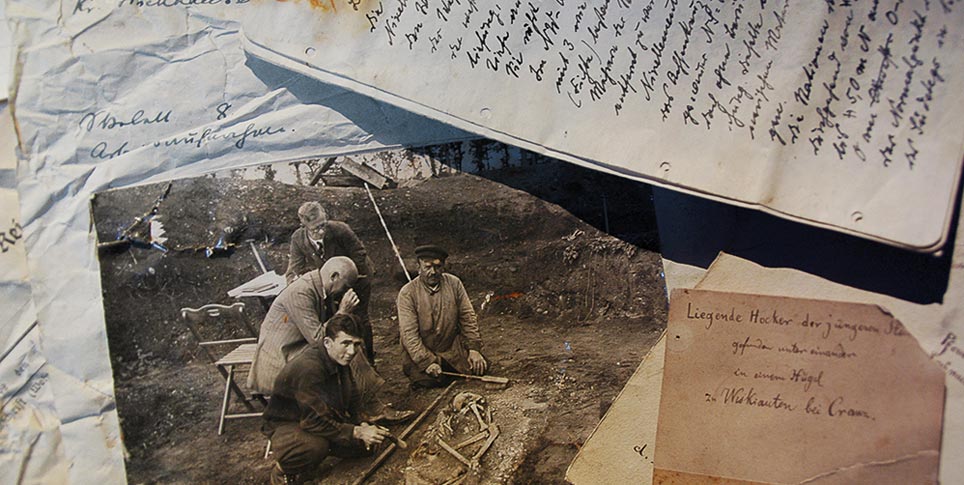

On the one hand, there are success stories such as that of Grete Mostny, a young archaeologist and anthropologist who left Austria in 1938 after her dissertation at the University of Vienna had been refused approval because she was classed as Jewish. It was with the help of personal contacts rather than academic networks that she fled to Chile, where she got a job in Santiago as a researcher at the Museo Nacional de Historia Natural. In 1954, Mostny achieved her international breakthrough as a scientist. The mummy of an 8-year-old boy had been found on the mountain of Cerro El Plomo near Santiago, at an altitude of more than 5,000 meters above sea level. Known as “el niño del Cerro El Plomo,” it has been dated at around 1550. Mostny secured it for the museum and pioneered the setting up of an interdisciplinary research team to examine this spectacular find. It immediately attracted international attention, because at the time it was the first freeze-dried Inca mummy to have been found and scientifically examined. Far too little is known about Grete Mostny and her scientific work outside Chile. Based on my research in Santiago de Chile, Vienna, and Berlin, I am currently preparing the first comprehensive scholarly article about her. On the other hand, there are many cases and individual biographies of emigrants – mainly Jewish – who were unable to regain an academic foothold in exile, or did so only with difficulty. Finding them continues to be a big challenge.

In addition to Jewish refugees and other scholars, are you looking at Nazi scholars who carved out a career in South America?

Yes, for example the chemist Armin Dadieu, who until 1945 was the National Socialist governor and Gauhauptmann of the Austrian province of Styria and who in 1946 was named on the second list of wanted Austrian war criminals. From 1948, at the latest, he worked in Argentina in the field of rocket fuel research, among other former Nazis, before returning to Germany in 1958. In 1962, he became the director of the Stuttgart Institute for Rocket Fuels, without any consideration of his National Socialist past. Argentina thus functioned as an important stopover in his career, a kind of scientific quarantine that furnished him with excellent political contacts.

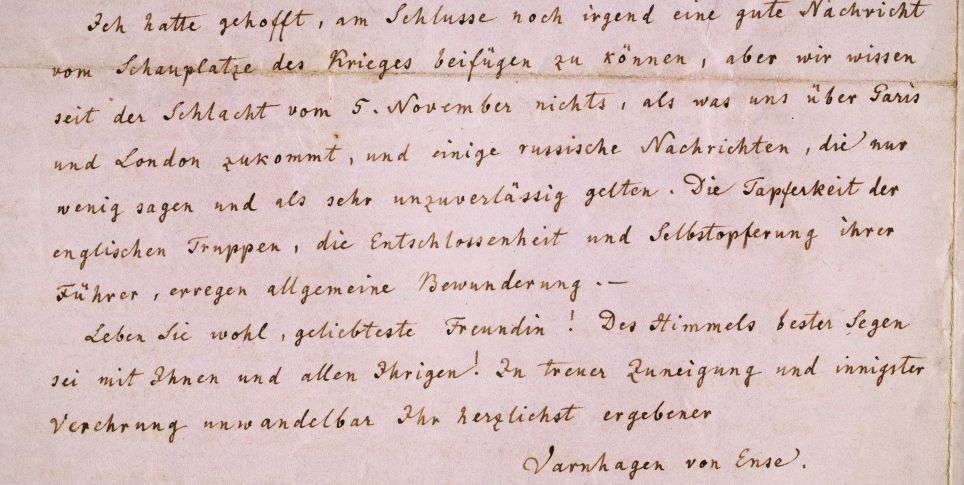

You spent the first quarter of this year at the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut (Ibero-American Institute) in the course of your research. Which material turned out to be especially fruitful? Did you make any unexpected discoveries?

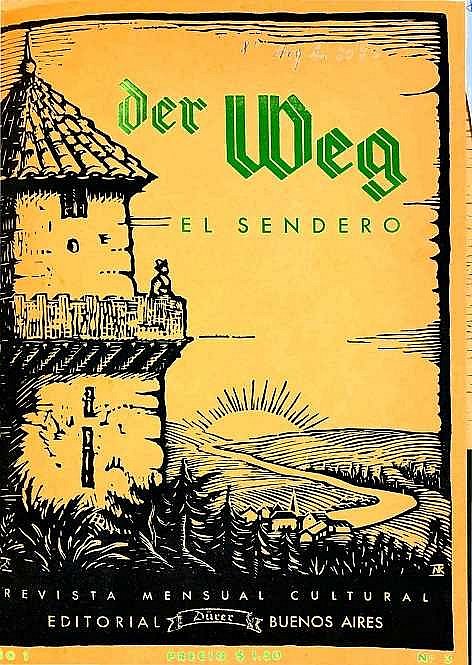

The IAI has almost completely documented the German émigré magazine Der Weg / El Sendero – that is unique in Europe. It was published from 1947 to 1957 in Buenos Aires. Among those who contributed articles to it were many former Nazis, including Austrians. Holger M. Meding has conjectured that the pen name “G. Helmuth” concealed the identity of the former concentration camp doctor Josef Mengele. Argentina was not the only place where the monthly was in demand: the ‘old guard’ or ‘die-hards’ also had eager readers and loyal subscribers in Vienna and Berlin. For my project, this magazine gives insights into a very interesting self-contained milieu.

Appeal to readers

Linda Erker is still looking for more scholars from Austria who went into exile in Latin America and would be very grateful for any information or contact via e-mail.

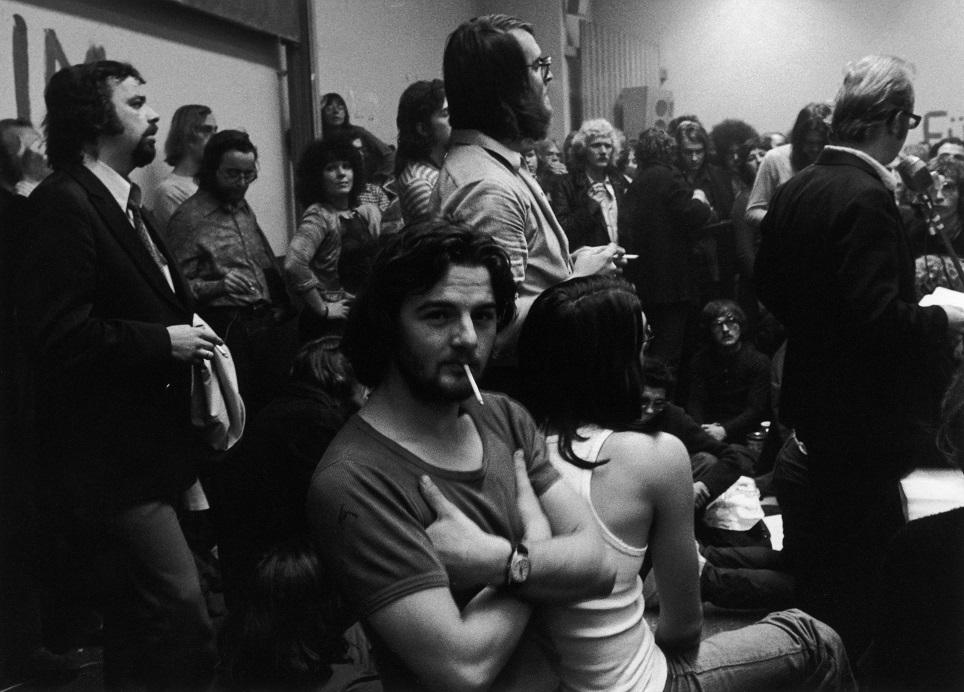

You also prepare exhibition concepts and organize events on historical topics. And you do volunteer work in historical and political education. What experiences have you had in this context? And how can we manage to keep history alive?

“History is made,” as the title of a song by the band Fehlfarben goes. The lyrics also say “forgetting is on the rise,” and I think we can only stop it spreading further if we act together. We can all help to shape collective knowledge of the recent past. Covid-19 and the distancing measures have made it clear to me, ex negativo, what is really important if you want to get history across: you can hold lectures via video conference and you can chat in virtual rooms, but nothing beats meeting in person, an open discussion, and informal conversations. I hope we will quickly get back into a direct mode and gather with other people in the physical world.

Berlin is a city in which history is strongly present. What do you notice here with regard to the politics of remembrance, in comparison to Vienna?

The history of the Nazi period and the memory of it are strongly present in both Vienna and Berlin. I have worked in the field of historical and political education for a long time, and in both cities the memorial and remembrance work is always underfunded and relies very much on voluntary helpers. Without being able to go into detail here, I see a greater willingness in Germany to make more money available in order to achieve a broader effect, as with the work done by the Federal Agency for Civic Education. In Vienna, there are many activists and associations, so their actions are much less centralized – with all the advantages and disadvantages that this entails.

Dr. Linda Erker (University of Vienna) conducted research at the Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut from January to March 2020 as part of her research project: Science Migration and Knowledge Transfer between Austria and Latin America (1930–1970).

Linda Erker's profile on the website of the University of Vienna