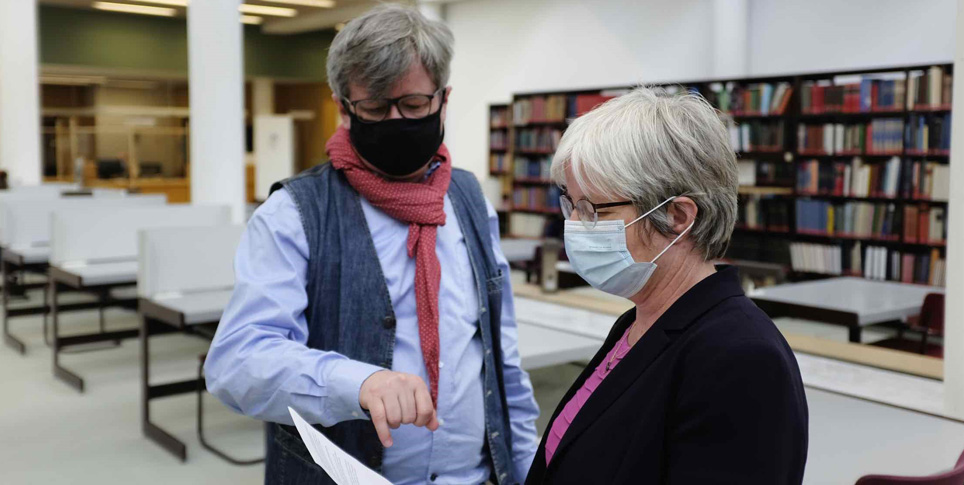

Martina Müller-Wiener is part of an international team searching for an Iraqi city that flourished from the period of late antiquity and the early days of Islam and has since vanished.

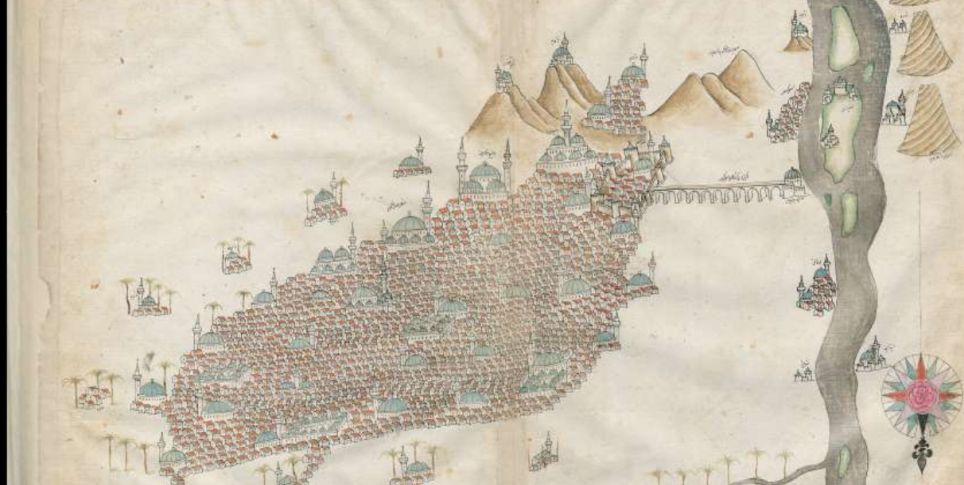

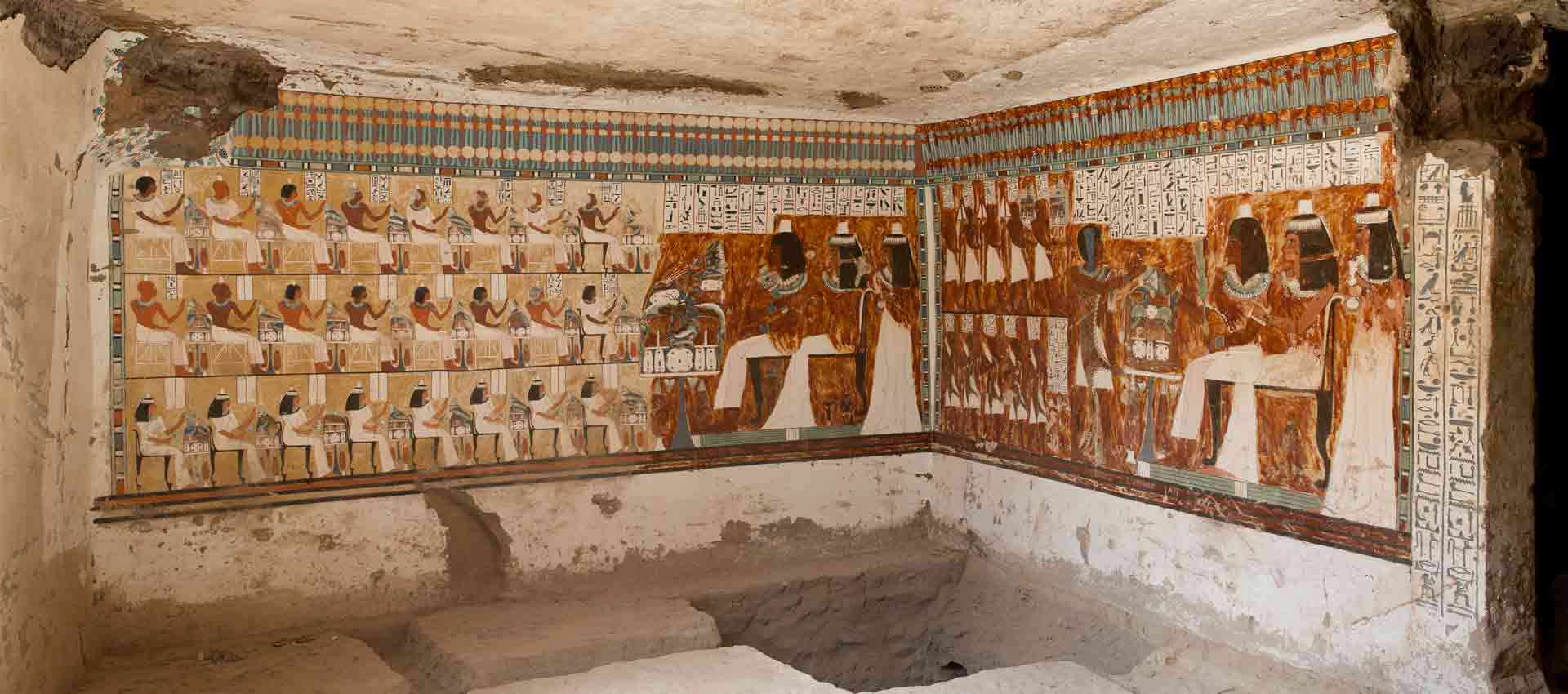

At the edge of the fertile alluvial plain of the Euphrates, in south-central Iraq, lie the cities of Najaf and Kufa. South of these two cities is a landscape of palm groves and fields, and it is here that archaeologists think the Arab cultural capital of al-Hīra once stood. In late antiquity and the early days of Islam (4th to 8th century A.D.), the city was a cultural center and the seat of local dynasties boasting magnificent palaces. It was celebrated in verse by famous poets who called the city home. The "splendor of al-Hīra" is anchored in the cultural memory of Iraq to this day, even though the city has now disappeared beneath the earth, says archaeologist Martina Müller-Wiener, who is the deputy director of the Museum für Islamische Kunst der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin (Museum of Islamic Art, National Museums in Berlin). "You could call it the Atlantis of Iraq," she says. "Although we know from the writings of Arab authors approximately where al-Hīra lies, we haven't yet discovered any actual remnants of the city."

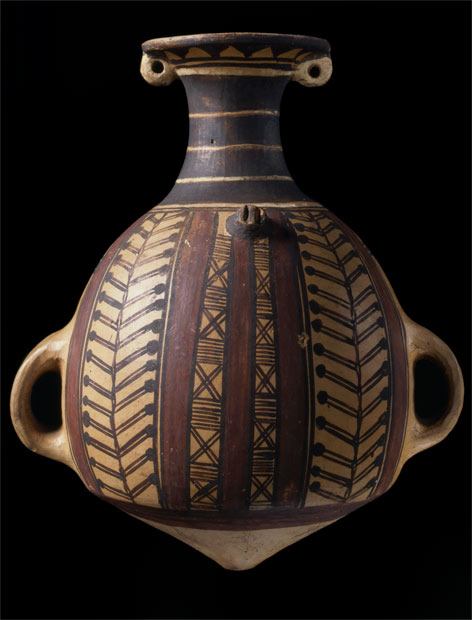

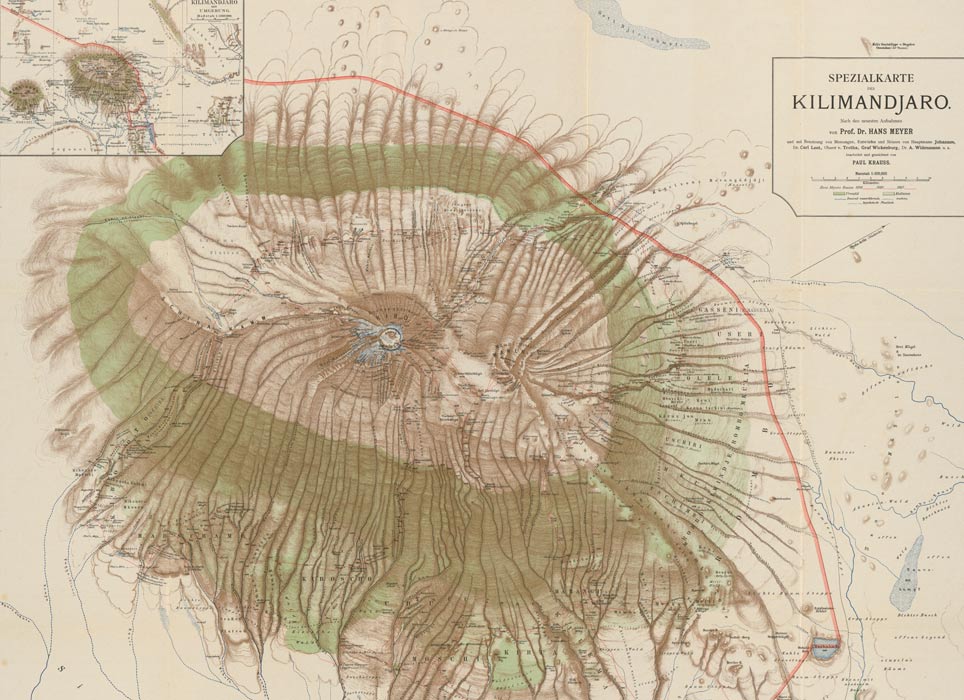

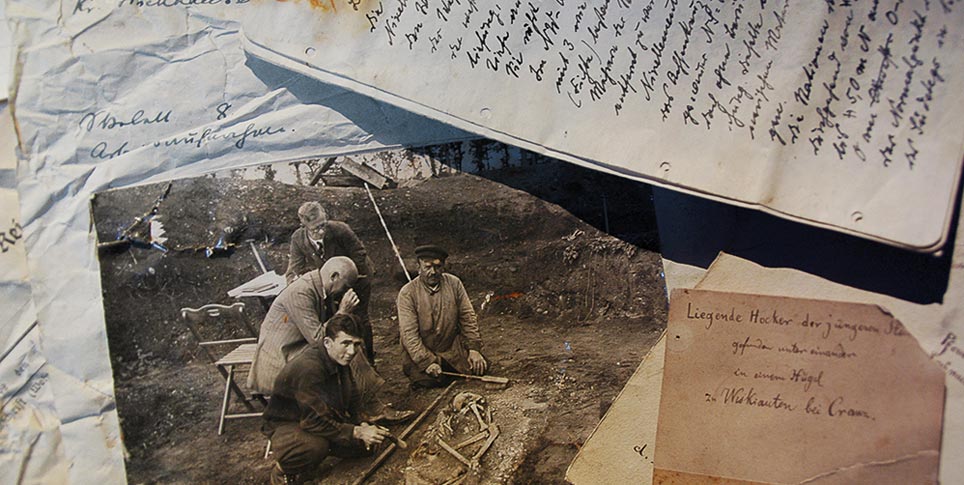

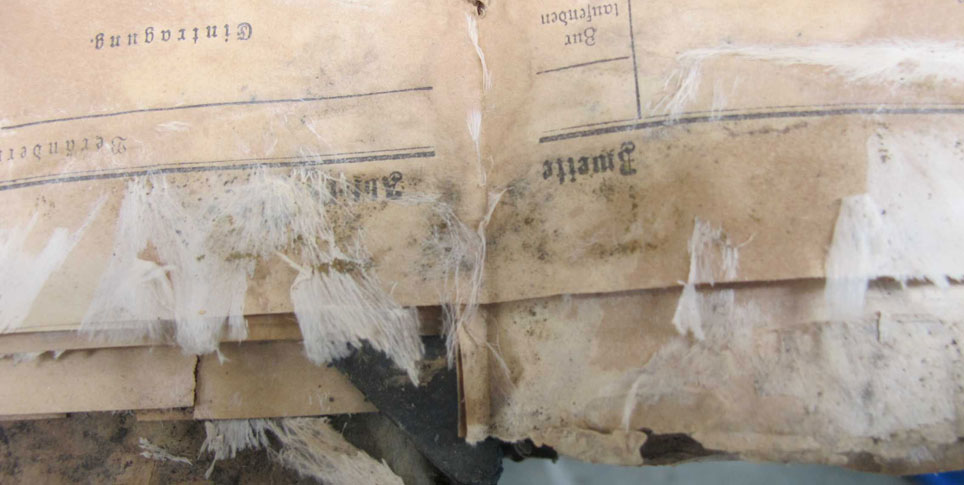

From 2015 to 2018, Müller-Wiener and her partners in this project, the Orient Department of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) and the Technische Universität Berlin (TU), conducted a survey of the land southeast of Najaf and Kufa. The participants conducted a systematic search for any structural remains of al-Hīra or pieces of pottery; the latter help to define a time frame to which the architecture could be assigned. Today, the flourishing nearby cities of Najaf and Kufa are becoming an ever-greater challenge to exploration of the lost city of al-Hīra. Najaf draws more pilgrims (primarily Shiites who travel from Iran) than any other city in Iraq, except for Karbala. The physical expansion of the two cities is increasingly threatening the historical area of al-Hīra. "Construction activity there is isn't subject to much regulation, so we're trying to support efforts by our local partners to set up archaeologically protected areas in order to safeguard whatever historical remains there may be," says Müller-Wiener.

"Unfortunately, we can’t always assume that conservation will be taken into account from the beginning. Just like everywhere else, there is an interest in preservation on the one hand, and there are commercial interests on the other. Then the issue is always who has the best negotiating position and support." Efforts to safeguard potential remains have met with some success in the past: "When plans were being laid to build a second runway at Al Najaf International Airport in the historical area of al-Hīra, we got together with our Iraqi colleagues and made sure that adequate preliminary investigations took place before construction began," Müller-Wiener says.

With her project partners, she drew up an approach for an environmental impact study and carried out the on-site investigations. "That was a very special kind of work," she explains. "We worked between the take-offs and landings at the neighboring airport, looking for archaeological remains of the historic city. We also used instruments provided by a project partner, Eastern Atlas, that gave us a view of the geophysical conditions beneath the earth. We were able to identify structures that were hidden beneath the surface and which indicated the presence, at one time, of a continuous expanse of buildings in that area."

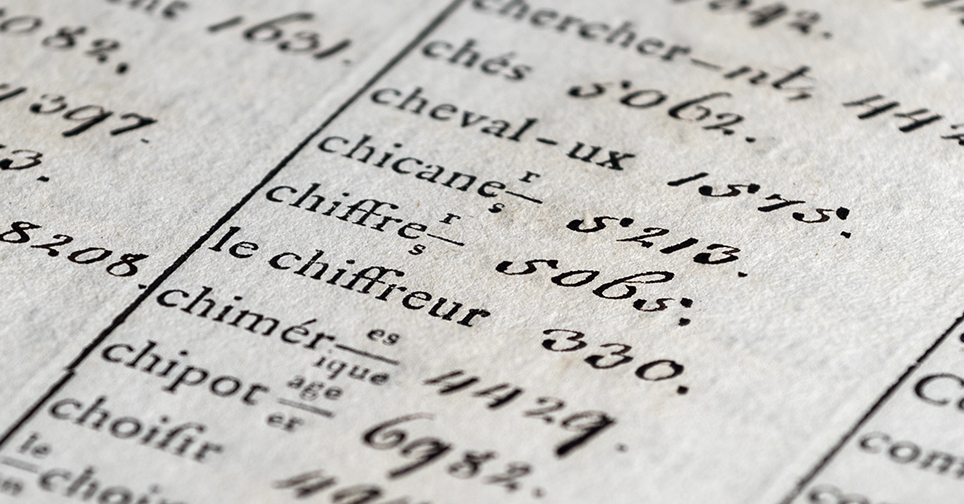

The archaeological finds that were secured between 2015 and 2018 produced a conundrum with regard to their chronology, however, as Müller-Wiener explains: "All of the data we were able to recover from them points to a later date than we would have expected for the al-Hīra that we are looking for. The finds that we discovered come from a phase that goes back into the 8th century, but we were looking for the 5th century – three hundred years earlier."

Cooperation partners

- Museum für Islamische Kunst. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Dr. habil Martina Müller-Wiener

- Deutsches Archäologisches Institut/Orient Abteilung, Dr. Dr. h.c. Margarete van Ess

- Technische Universität, Berlin/Fachgebiet Historische Bauforschung, Dr.-Ing. Martin Gussone

- Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage

- Eastern Atlas Berlin, Burkart Ulrich

- Universiteit Leiden/Digital Archaeology, Prof. Dr. Karsten Lambers

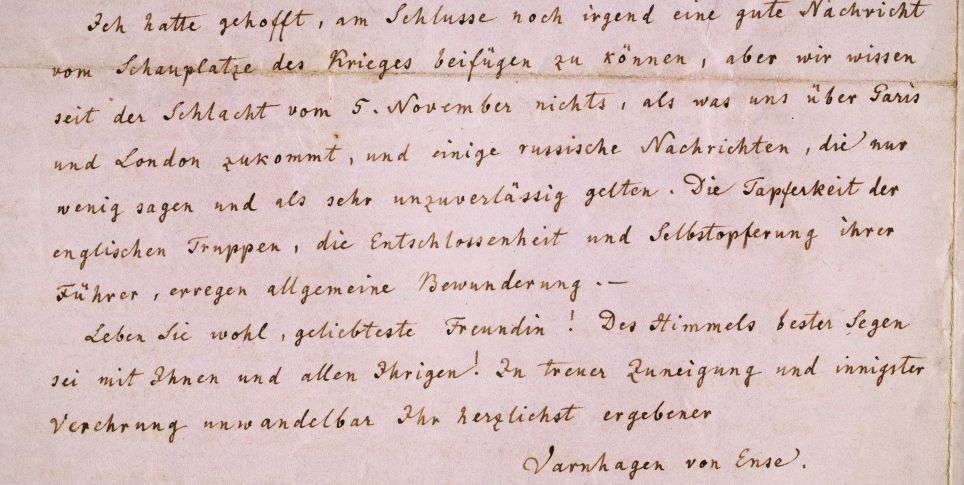

The survey was only the first phase of a larger plan to investigate al-Hīra more closely. "That's the usual approach with a project like this: You first get an overall view of a broad area and check to see which spots are suitable for doing excavations and taking a more detailed look," explains Müller-Wiener. The next step will be the excavation campaign, which has been divided into five subprojects. To that end, Müller-Wiener and her fellow archaeologists, Margarete van Ess from the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) and Martin Gussone of the Technische Universität Berlin (TU) submitted an application to the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) to request funding for the follow-up project, titled "Late Antique and Early Islamic Hira: Urbanistic Transformation Processes in a Trans-regional Contact Zone." That application was approved in 2020.

The excavation was supposed to begin in the fall of 2020, but unfortunately that schedule was thrown off-kilter by the coronavirus pandemic. "Iraq isn't an easy place to work as it is," says Müller-Wiener. "We're very constrained, especially because of the security restrictions, and the coronavirus pandemic didn't make things any easier, of course."

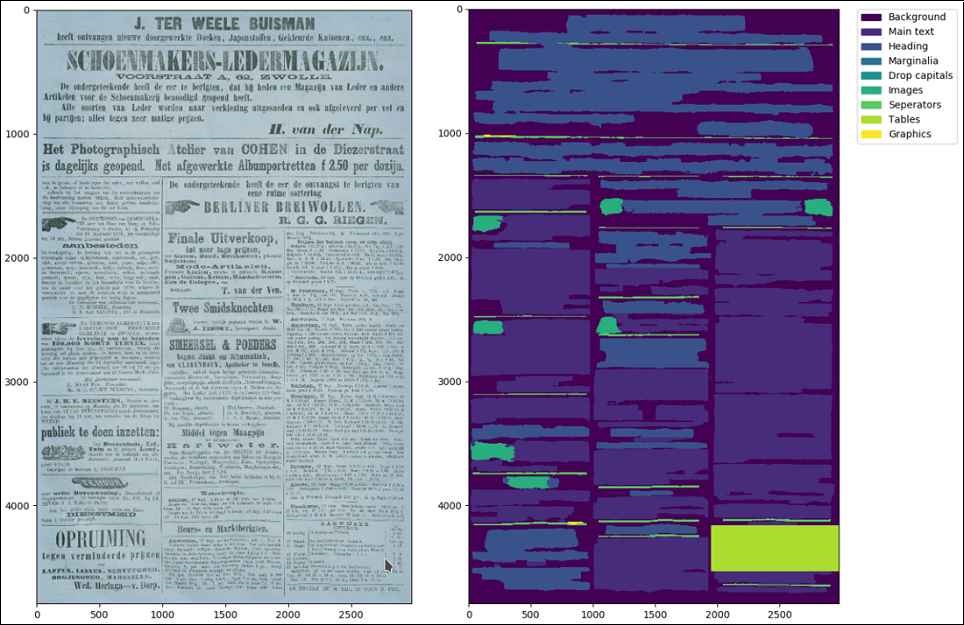

Despite all that, one of the five subprojects is scheduled to start in the spring of 2021: A doctoral student associated with the TU Berlin and Leiden University is currently developing an innovative AI-based technique for evaluating the prospecting data gathered from 2015 to 2018. "The evaluation used to be performed manually. But that results in a subjective picture, so people have been trying for quite a while now to make the process more objective, to accelerate it and generally optimize it," says Müller-Wiener. "An adaptive artificial intelligence algorithm allows us to put all that on a different footing."

Ultimately, the goal of all this work is to obtain additional evidence that would allow the team to date the archaeological finds and thereby make some progress in filling in a timeline for al-Hīra. "We want to make a fundamental contribution to the subject of early Islamic urbanization with this research, since Iraq was the place where most of the new cities were being founded during this period. For a long time, no research was possible because of the fighting, although the area can shed a lot of light on the early days of urban development. I think we'll really make a substantive contribution to basic research with our work."

The team of international scholars participating in this pivotal research includes the building archaeologists Martin Gussone, Catharine Hof, and Ibrahim Salman, as well as researchers from the Iraqi State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH). "To work in Iraq, you have to apply for a license. Local colleagues provide support. You work with them and publish the results together. It's also a big plus that Margarete van Ess is involved. She has been working for more than twenty years in Iraq and has good contacts there." One might think that such a diverse team could give rise to complications, but Müller-Wiener says that is not the case: "I find the different perspectives to be very invigorating and enriching. In our field, cooperation of this sort is absolutely normal, and we have well-practiced workflows and routines."

She hopes that, in the fall of 2021, she can finally be at the site with her colleagues and can start excavating: "I'm really looking forward to it – to standing there, under the blue sky, and starting to dig."