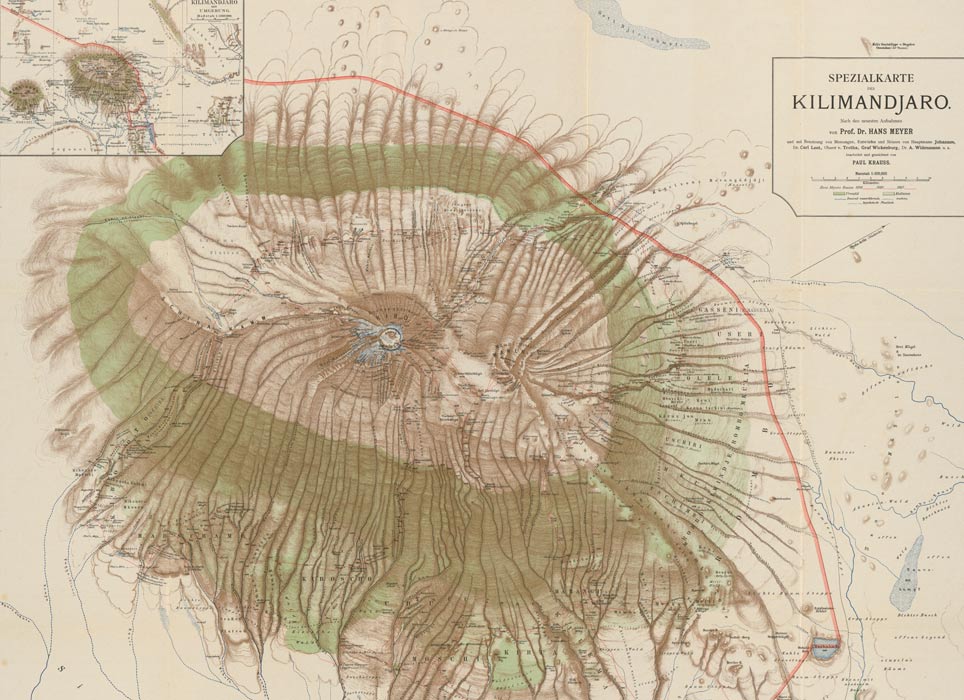

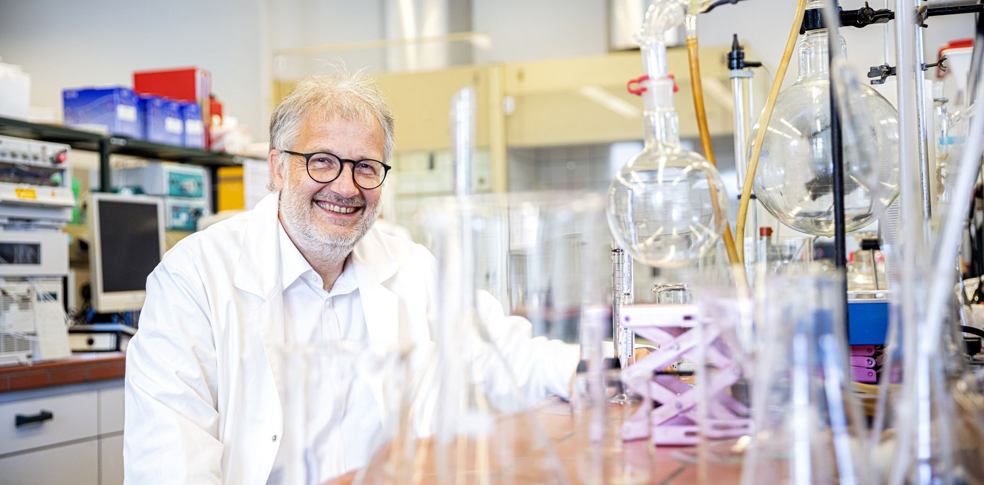

In colonial times, many of the glaciers, peaks, and cones on the highest mountain in Africa bore German names. Wolfgang Crom from the Staatsbibliothek is looking for patterns in the way that they were named.

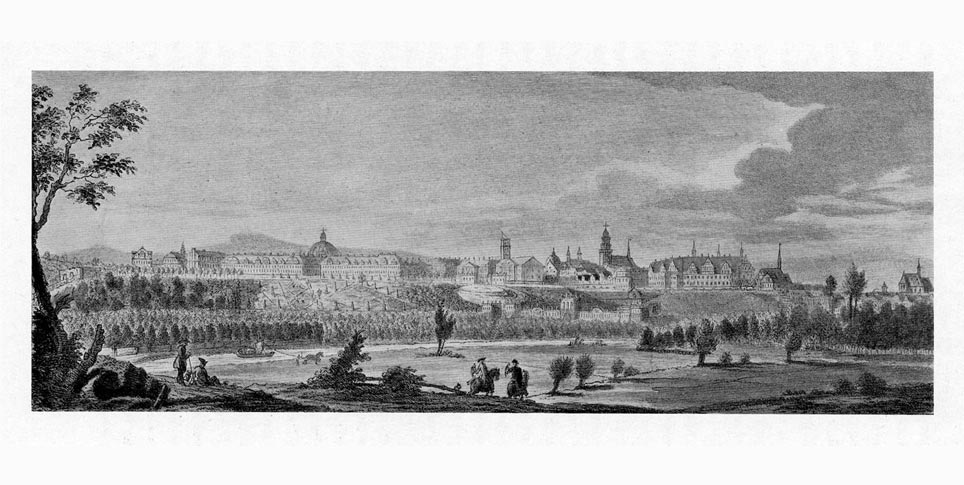

Wolfgang Crom has never been to Kilimanjaro himself, yet he knows it like the back of his hand: especially the glaciers with their tongues and crevasses, and the rock faces, hills, and volcanic cones. A geographer by training, he is interested in the various landscape features of Africa’s highest mountain, in particular their names and descriptions, especially the colonial ones. From 1885 to 1918, Kilimanjaro was in the possession of the German Empire, as part of the colonial territory of German East Africa. Following the logic of imperialism, its highest peak was named after the reigning emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm.

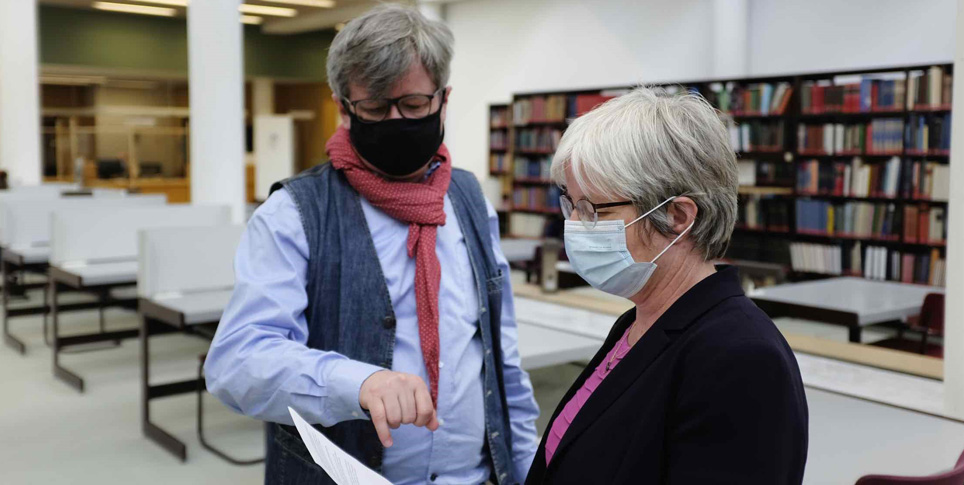

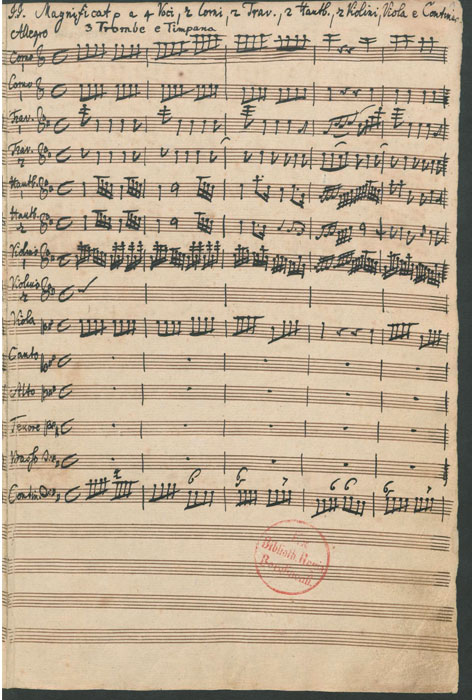

You can see the name in maps dating from that time. But how exactly did it come about? Were toponyms (the names of natural landmarks) bestowed and used according to a principle of some kind? And what do we mean by the term “colonial cartography”? These are some of the questions that Wolfgang Crom is trying to find the answers to. As the head of the maps section of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Berlin State Library), he has the source material at his fingertips. The library’s collection contains 1.2 million maps on paper, plus 250,000 digital maps, tens of thousands of views, atlases, and plans, as well as 800 globes. During the next few months, they will all be brought together in the newly renovated library building on Unter den Linden in Berlin. “We are in the middle of the move from the building on Potsdamer Strasse. Right now it’s the turn of the globes,” says Crom. Research work will be much more convenient as a result. Scholars and students shouldn’t have to wait more than an hour before the document they have requested is ready for them to look at.

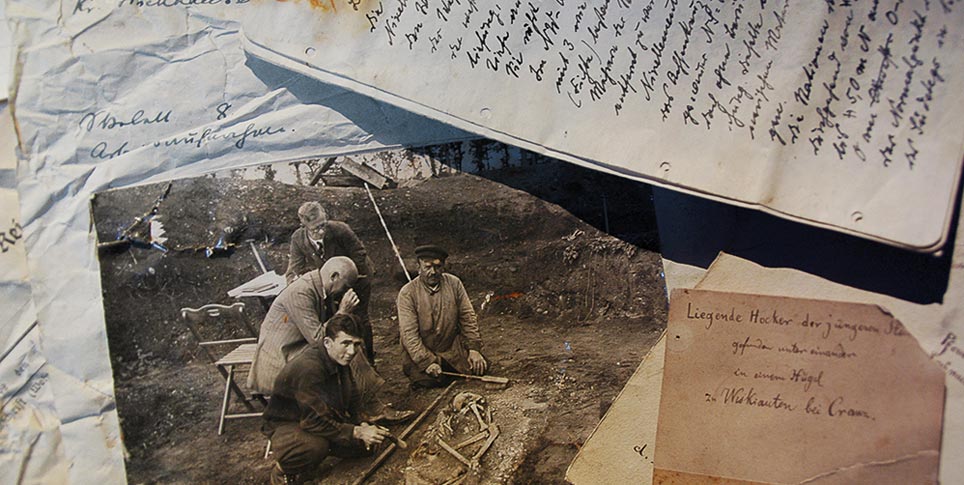

The maps mentioned above, based on bearings taken locally, belong to the collection that Hans Meyer drew up and published after his expeditions to Mount Kilimanjaro. As the offspring of a family from Leipzig that had made a fortune in publishing (notably the Meyers Konversations-Lexikon encyclopedia), he was able to undertake many scientific expeditions around the world. He was also a child of his time, who was complicit in racism and did nothing to counter the often brutal oppression of local people. He made several attempts to climb Mount Kilimanjaro before he succeeded in reaching the highest point of the crater’s rim in October 1889. Never before had a European climbed the mountain. North of the Mediterranean, people had long thought it impossible that a snow-capped mountain could exist in tropical Africa. Snow on Mount Kilimanjaro? It must be a delusion!

Meyer saw himself as a scientist too. Above all, he sought recognition from glaciologists at a time when the study of glaciers was just emerging as a scientific specialism in its own right. In fact, he was the first to prove that there had been a distinct ice age in the high-altitude mountain ranges of tropical East Africa, which had left behind the typical spectrum of geological formations. He showed that the glaciers were also retreating on Kilimanjaro. He named the Credner, Drygalski, Penck, and Heim glaciers after well-regarded glaciologists. Other glaciers received the names of important scientists: the Rebmann-Gletscher, for example, was named after Johannes Rebmann, a missionary and linguist who in May 1848 became the first European to see Kilimanjaro, which he subsequently described.

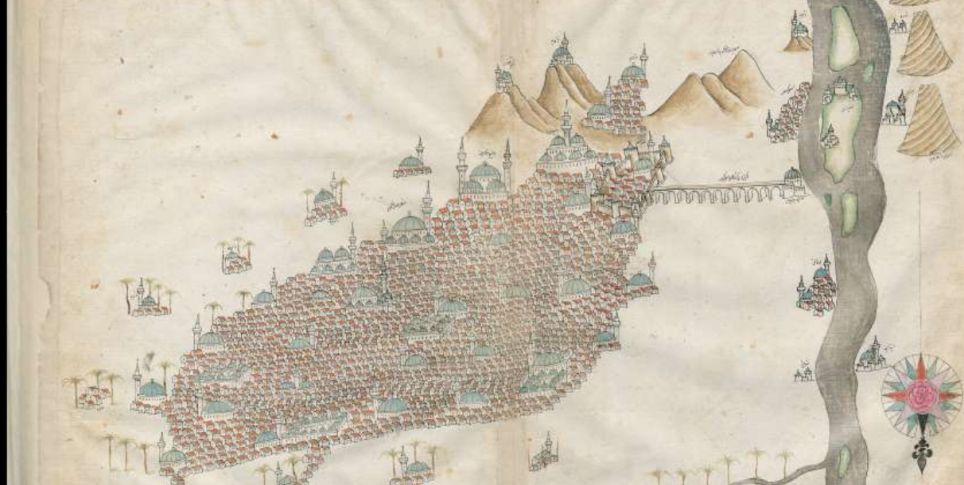

Maps don’t just represent a geographic area. They create facts.

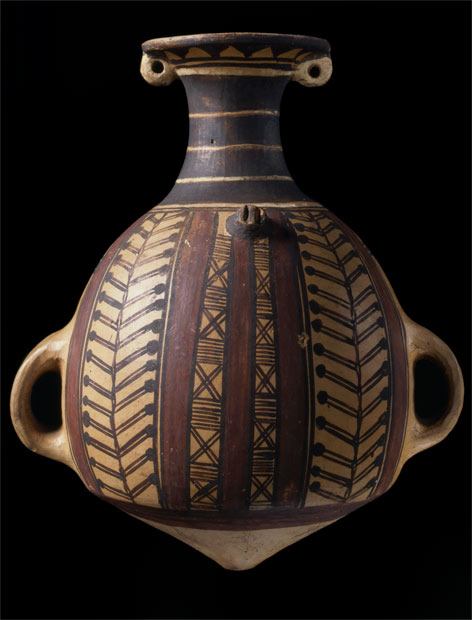

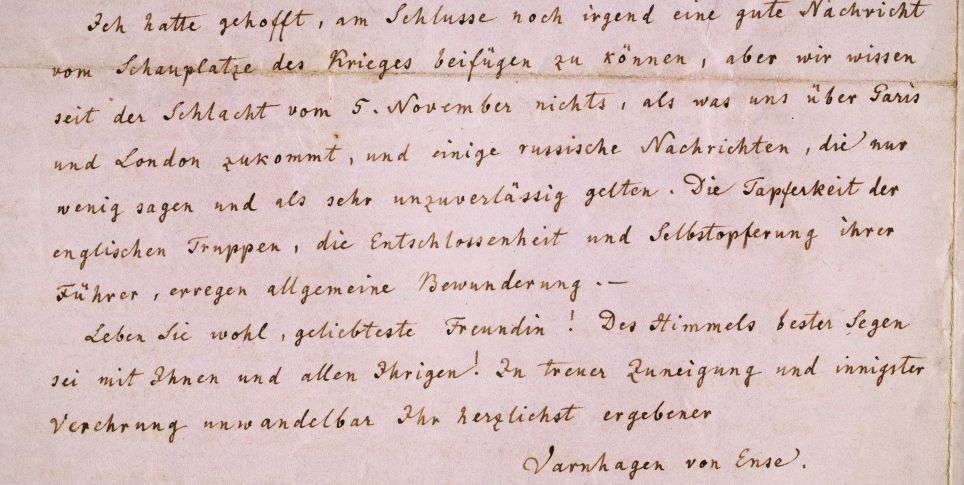

So Meyer did not choose names by chance. This knowledge is significant for us today, according to Wolfgang Crom, studying the maps in Berlin. “It is also the case that Meyer took a relatively restrained approach for a colonizer and respected the terms used by the local population,” he explains. Sure, there are Kaiser Wilhelm Peak and Bismarck Hill and Moltke Hill. “But Meyer did not name any of the places he explored after Carl Peters, the imperial high commissioner who ruled the Kilimanjaro area with cruelty,” says Crom. Instead, Meyer’s works contain many names of caves, lakes, and watercourses that were used by local ethnic groups, and which he took the trouble to find out in person. One such is the Muë brook, as it was called by the Jagga, a people living on the southern flank of the mountain range, who are still known for their expertise in water management.

Maps are commonly seen as symbols of power. They don’t just represent a geographic area. They create facts. Of course, the maps of Kilimanjaro also served to encourage people back in Germany to identify with colonization. “To put it simply: the colony entered the living room and the classroom via the map.” Exonyms (place names and terms used by people living elsewhere, in this case Germany) expressed economic, military, or scientific superiority as well as implying that a place naturally belonged to the empire and reinforcing the colonial power’s own identity.

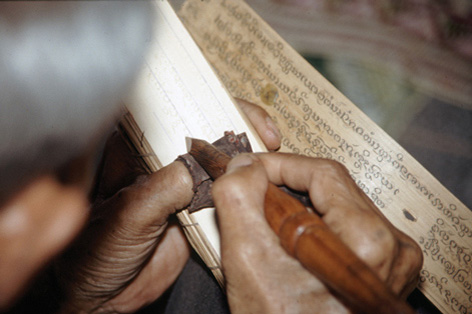

Meyer, however, also had other motives when deciding on names. So he chose German names mainly for places that apparently had no indigenous name, and for those that were named differently by different ethnic groups – or if there was uncertainty about the translation. It was normal practice for European colonizers to ask local people for the names of rivers, places, or plateaus – but sometimes they simply did not understand or the answer, or misinterpreted it.

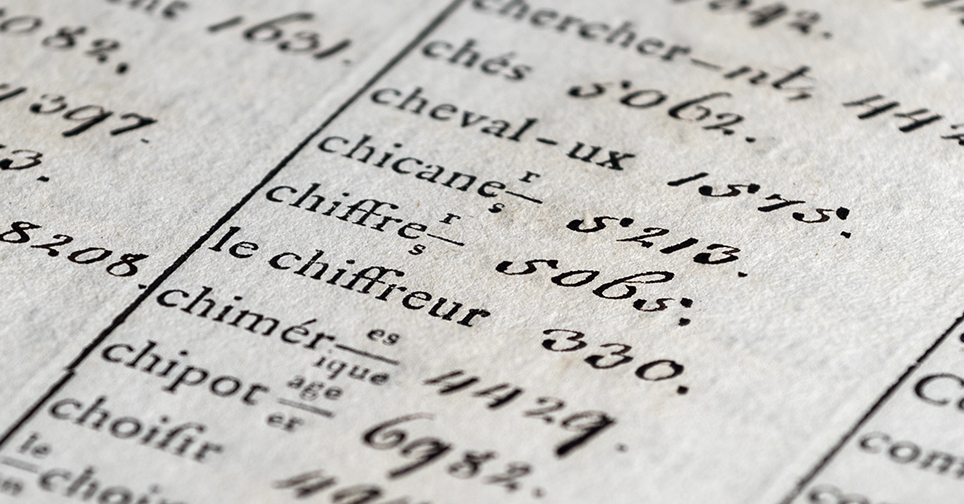

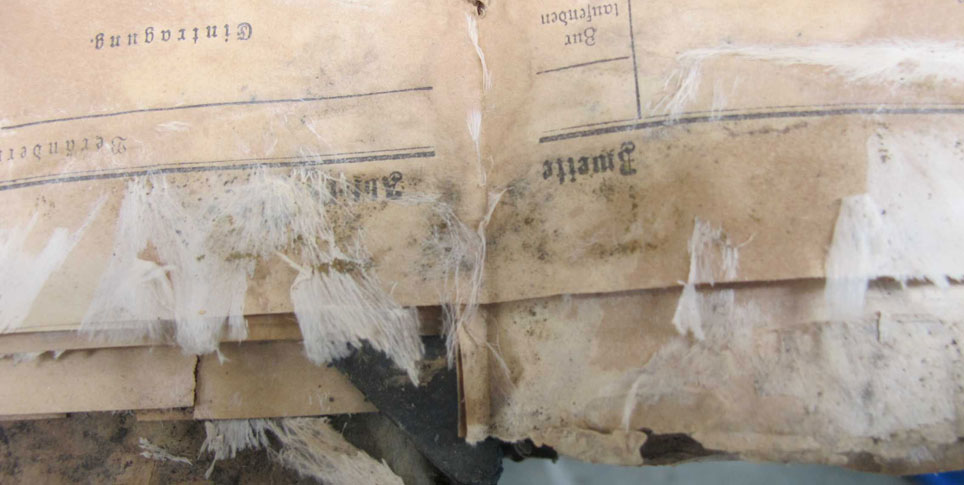

Colonial administration, however, required clarity in such matters. Since 1892, they had been the responsibility of a “commission for regulating the uniform spelling and pronunciation of geographic names in German protectorates”, which in general followed the principle of giving preference to indigenous names. Its task was to decide the official names. The fruits of its labor are evident in the “Great German Colonial Atlas”, a work of impressive scope and precision that was published in 1901 by the colonial cartography institute on behalf of the German Foreign Office, which financed it. Again and again, the meticulous cartographers had to revise individual sheets to show features discovered by the latest geographic expedition, or to include new names.

Regions were mapped in order to develop, plan and govern them as colonies. But how did the names get onto the maps? It is not always clear. What about the mountain itself: Kilimanjaro? The name was first introduced to Europe by Johannes Rebmann. But where did he get it from? And might he have misunderstood something? Rebmann claimed to have heard it from the inhabitants of the coastal region around Mombasa, where he had been stationed as a missionary. He thought that it meant “big mountain”, but later he mentioned another name: Kibo, which in the language of the Jagga, who live on the mountain itself, means “snow” or “cold”. But what were they referring to, exactly? The fact that the massif has not just one but three peaks, which were presumably distinguished from each other, complicates the business of interpreting and attributing names. “It can no longer be ascertained whether Kilimanjaro was originally a toponym at all, and whether the local populations actually had a name for the mountain range as a whole,” concludes Wolfgang Crom. One thing, at least, is certain: the term “Kilimanjaro” ultimately became established as the name of the entire volcanic massif, perhaps because it sounds so exotic to European ears.

The British may have been glad that all the hills, crests, glaciers, and ridges were already identified by a name on the map when they later took over the region as a mandate. Even before that, the British General Staff and the surveyors of the British Colonial Office had begun reprinting the detailed German maps – thereby adopting many of the place names bestowed by the German colonizers. This is another important conclusion that Wolfgang Crom has drawn from his research: some of the German names on Kilimanjaro are still in use internationally. Tourists who want to climb the highest mountain in Africa can still find the Bismarck Towers on their trekking maps, for example. The Hans Meyer Notch cuts through a crater rim, the volcanic Hans Meyer Ridge rises between two glaciers – and the highest peak of Mawenzi, the second summit of the Kilimanjaro massif, is internationally known as Hans Meyer Peak. Nowadays, the glaciers are deeply fissured and have almost completely melted away. Their names will live on in the old maps nevertheless.k. Die Gletscher sind stark zerklüftet und längst fast völlig geschmolzen. Ihre Namen in den alten Karten bleiben.